Jesse Fried is the Dane Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. This post was authored by Professor Fried. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Short-Termism and Capital Flows by Professor Fried and Charles C. Y. Wang (discussed on the Forum here).

President Donald Trump and Senator Elizabeth Warren rarely see eye-to-eye on policy, and frequently attack each other personally. But they have finally found common ground: both seem to believe that investors in public firms are too powerful, and the solution is to better insulate corporate directors from shareholders.

In August, each offered a proposal aimed at shielding boards from investor pressure. Senator Warren introduced legislation—the Accountable Capitalism Act—that would federalize corporate law and force all U.S.-domiciled firms with revenues exceeding $1 billion to hand over at least 40% of board seats to employees. The Act would also alter fiduciary duties to require directors to consider all stakeholders, not just shareholders. President Trump, in turn, asked the Securities and Exchange Commission to study the possibility of eliminating quarterly reporting for public firms and allowing boards to share the information with investors only semi-annually.

Bipartisanship is generally a good thing, especially in this era of hyper-polarized politics. But the consensus view that public shareholders are distorting firm behavior—a phenomenon often labelled “quarterly capitalism” or “short-termism”—is very wrong-headed. And the remedies emerging from this consensus, particularly Senator Warren’s, could profoundly damage the U.S. economy.

In the absence of any solid evidence that shareholders harm firms, the case for weakening investors has been based on myths, misconceptions, and misleading figures. For example, the press release for Senator Warren’s Accountable Capitalism Act recycles the erroneous claim that America’s biggest companies dedicate 93% of their profits to shareholders—funds that supposedly would have gone to workers or long-term investment.

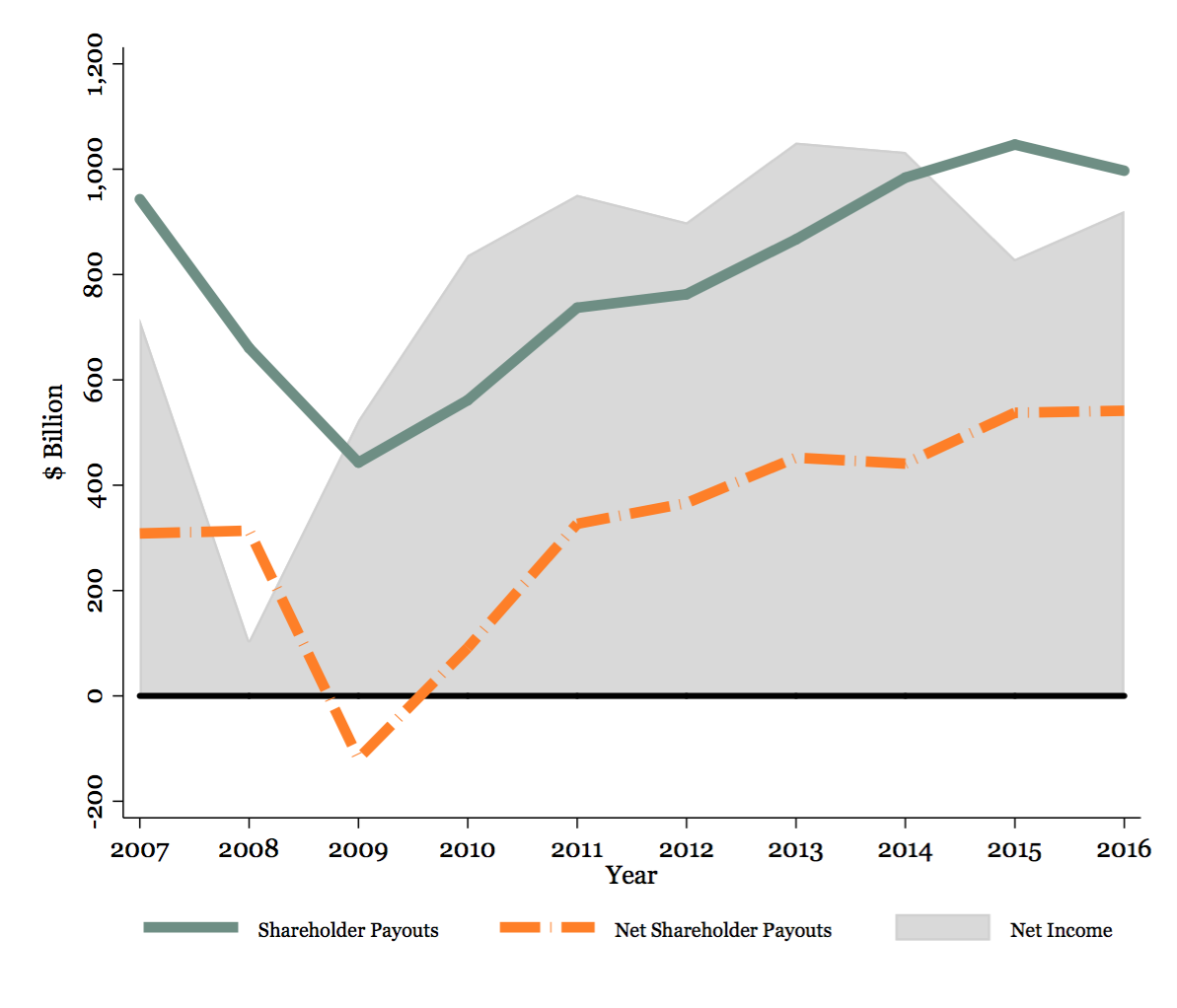

But as my research with Charles Wang shows, the 93% payout figure is gross—it includes dividends and stock repurchases, but excludes equity issuances that move capital in the opposite direction. Net shareholder payouts are much lower. Figure 1 below displays both shareholder payouts (dividends and repurchases) and net shareholder payouts (dividends and repurchases, less issuances) for all public firms during 2007-2016, against a backdrop of net income. As Figure 1 makes clear, net shareholder payouts are only about 40% of shareholder payouts during the period. (Our research focuses on 2007-2016 but the results are almost identical for 2008-2017, the latest decade for which data are available.)

Another problem with this 93% figure is that the denominator—net income or profits—reflects what’s left after the firm has allocated a portion of its income to deductible expenses, including wages and R&D. For understanding the effect of net shareholder payouts on investment capacity, a better denominator is “income available for investment”: net income plus a firm’s after-tax R&D costs. Across all public U.S. firms, our research shows, net shareholder payouts during the period 2007-2016 were only about 33% of income available for investment, leaving approximately $7 trillion for that purpose.

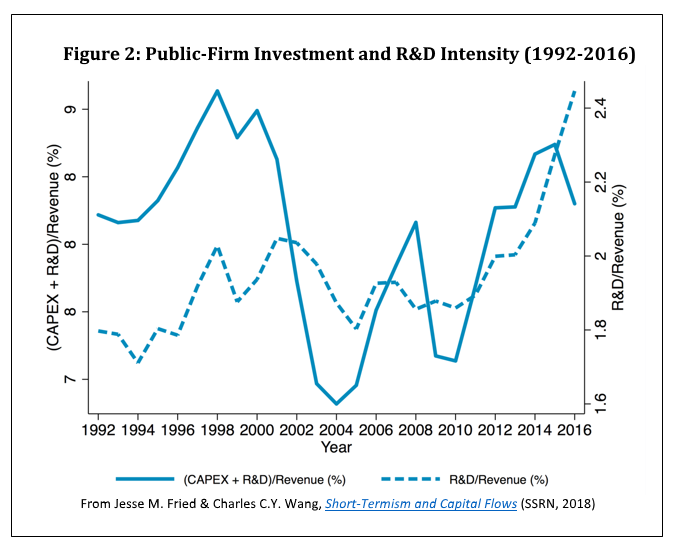

In fact, my research with Charles Wang shows that much of this $7 trillion has gone into long-term investment. As Figure 2 below illustrates, the overall investment intensity at public firms, as measured by the ratio of capital expenditures (CAPEX) and R&D to revenue, was higher during 2012-2016 than during any other five-year period since the late 1990s boom. R&D intensity, the ratio of R&D to revenue, ended the period at an all-time high.

Nor are public firms financially constrained from engaging in additional investment; they had ample dry powder. Indeed, cash balances climbed from about $3.3 trillion in 2007 to about $5 trillion at the end of 2016. The misleading 93% figure and others like it paint a picture of shareholders starving firms of capital, crippling their ability to invest; the real figures do not.

Decisions about how to deploy capital in public firms—whether to invest it, store it for the future, or pay it out to investors—occur within the context of a market-based system. Investors provide capital to corporate managers under an agreed-upon allocation of decision-making power. If managers have a credible plan for long-term investment, investors can sit patiently as the firm spends years running up losses (such as Amazon, in its early years). When a firm can’t profitably deploy capital, investors want the cash returned to them so it can be invested in other firms, public and private. Overall, the market generally works, allocating financial resources to where they are most needed.

The ironically-titled Accountable Capitalism Act would endanger this system by making corporate insiders accountable to nobody but themselves. When 40% of a firm’s board consists of managers or their direct or indirect reports, outside investors would need to win almost every other seat to wrest control from incumbents. While this feat would be difficult even under existing arrangements, the Act’s new stakeholder-oriented fiduciary duties could make it all but impossible—by justifying directors’ use of extreme anti-takeover defenses to protect their board seats. And even if investors could gain a majority of board seats, these fiduciary duties could be used to prevent the investors from rationally allocating firm capital from inside the boardroom.

The Act’s effects can easily be predicted: capital would be trapped in cash-rich firms and mis-spent, the flow of capital from larger public firms to smaller public and private firms would dry up, and wealth would be transferred from public investors to corporate insiders. Firms looking to raise cash would find it harder. After all, why would investors hand funds over to unaccountable directors? Over time, capital would flee the country, followed by jobs. To be sure, employees of existing firms may feel more secure, at least in the short run. But there will be fewer opportunities in the U.S. for their children.

Of course, some firms may succeed in escaping the Act’s reach, either by domiciling outside the U.S. or by splitting themselves into smaller pieces. But these circumventions would give rise to other costs to the American economy, such as reduced operational efficiencies and a transfer of corporate tax revenues to other jurisdictions.

The Act could also be expected to lead to additional distortions down the road. Once corporate law is federalized, Congress will be tempted to use its foot-hold in corporate governance to add more mandates and restrictions, ostensibly to address other “problems” in corporate America, but actually to benefit key voting constituencies and campaign financiers. In short, the Act would put American crony capitalism on steroids.

President Trump’s proposal—which he tweeted after chatting with CEOs at his golf course—would also reduce corporate accountability, but through a different channel: by depriving shareholders of up-to-date information needed to monitor management. The CEOs whispering in Trump’s ear apparently told him that moving from quarterly to semi-annual disclosures would encourage boards to focus more on long-term investment. But, as my research with Charles Wang shows, R&D is at a record high and overall investment spending by public firms appears quite robust. Thus, it’s far from clear such encouragement is needed. In any event, evidence from the U.K. suggests that a reduction in disclosure frequency does not increase investment.

For most firms, the main effects of moving to semi-annual reporting will be profoundly negative: investors will find it harder to assess management and the value of their shares, and corporate insiders—and their tippees—will have more non-public information on which to trade. As a result, stock prices will be lower and firms going public will find it harder to raise capital.

To be sure, there could be certain public firms where both managers and outside investors prefer semi-annual over quarterly reporting, because the costs of more frequent disclosures exceed the benefits. Thus, the SEC should consider permitting firms to adopt semi-annual reporting after managers obtain approval by outside investors or at the IPO stage. But the CEOs pushing for semi-annual disclosures want the SEC to let them unilaterally reduce reporting frequency, even when it would hurt investors.

Perhaps President Trump and Senator Warren offered these ideas during the summer doldrums to rally their bases, or to provide material for Twitter, without actually expecting them to go anywhere. But there is a growing bipartisan consensus that excessive shareholder power is a critical problem facing America—notwithstanding the absence of any compelling evidence. This consensus creates a real risk that one or both of their policy proposals could be adopted, either in this administration or the next one.

Print

Print