David F. Larcker is James Irvin Miller Professor of Accounting at Stanford Graduate School of Business; Brian Tayan is a Researcher with the Corporate Governance Research Initiative at Stanford Graduate School of Business; and Edward Watts is a Ph.D. student at Stanford Graduate School of Business. This post is based on their recent paper. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Carrots & Sticks: How VCs Induce Entrepreneurial Teams to Sell Startups, by Jesse Fried and Brian Broughman (discussed on the Forum here).

We recently published a paper on SSRN, Cashing It In: Private-Company Exchanges and Employee Stock Sales Prior to IPO, that examines the practice of allowing the employees of private companies to sell vested equity awards prior to IPO and the features of private-company marketplaces that have arisen in recent years to facilitate transactions with investors interested in purchasing shares of these companies. We rely on two unique data sets: a survey of private (pre-IPO) companies and sample transaction data from SharesPost, a leading private-company marketplace.

Companies in the United States are staying private longer. During the period 1996-2000, the average company completing an initial public offering (IPO) was 6 years old at the time of the offering. In the early 2000s, the average age rose to 8 years. Following the financial crisis, it increased to 10 years. At the same time, the value of private companies has increased. Currently, almost 200 companies globally have a private-market valuation above $1 billion. The largest 15 of these are collectively valued at $300 billion.

The trend of staying private longer has important implications for companies and their employees. Equity compensation is a significant component of pre-IPO pay packages. It is used to align the interests of employees and owners by tying compensation to firm profitability and performance. Equity awards are used to attract employees who are more optimistic about a firm’s prospects, have a higher tolerance for risk (i.e., are more risk-seeking), and have potentially greater motivation to pursue firm objectives. Because equity awards in a private company are generally illiquid (i.e., there is not an active market for selling these equity awards), they also serve as a retention tool in that employees generally must remain with the company until a liquidation event (sale or IPO) in order to convert these awards to cash.

With companies staying private longer, employees holding equity in these firms are restricted from monetizing an illiquid asset that they might need to support their cost of living. As the value of the company rises, they are also exposed to a concentrated investment portfolio with a significant portion of their net worth invested in a single company and no readily accessible public market mechanism through which to diversify.

Secondary Markets for Private Companies

The pre-IPO marketplace has traditionally been dominated by networks of venture-capital firms, private placement agents, brokers, and banks. These markets have historically been fragmented and opaque, severely limiting access and transparency for potential investors. In the response to the trend of companies staying private longer, a number of secondary private-company marketplaces have evolved to facilitate transactions between employees or early stage investors wishing to liquidate a portion of their holdings and qualified buyers. Buyers generally include wealthy individuals, venture-capital firms, hedge funds, private-equity firms, and institutional investors.

Private-company marketplaces, however, are not uniform in their approach to facilitating transactions in private-company securities, and the various players have developed somewhat different platforms to meet customer needs. Examples include the following:

SharesPost. SharesPost, founded in 2009, is one of the oldest private-company marketplaces. A member of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) and the Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC), SharesPost functions as an over-the-counter marketplace where sellers list securities available for sale. It employs private securities specialists to help navigate company restrictions on the sale of stock, including any right-of-first refusal on tendered shares. It also provides basic information on securities, such as minimum sales price, historical volume and price data, and financial reports if available. Buyers generally must meet the accreditation standards of the Securities and Exchange Commission. Buyers have the option of working with third-party brokers to arrange a transaction but are not required to do so. SharesPost currently has an inventory of $3 billion in private-company shares available for sale. In addition to its marketplace offerings, SharesPost facilitates direct investment into late-stage venture-backed companies through its SharesPost 100 closed-end fund.

Equidate. Equidate, founded in 2014, uses an active order book to provide liquidity for private company employees and allows customers to submit bid, ask, and limit orders—a practice closer to how public equity exchanges function. Equidate partners with sophisticated investors (such as venture capital firms and hedge funds) to facilitate transactions. They also work directly with companies (such as Spotify) to implement company-approved liquidity programs for their employees. Equidate contracts with an affiliated broker-dealer and outside law firm to facilitate transactions and charges each side of the transaction a 5 percent fee.

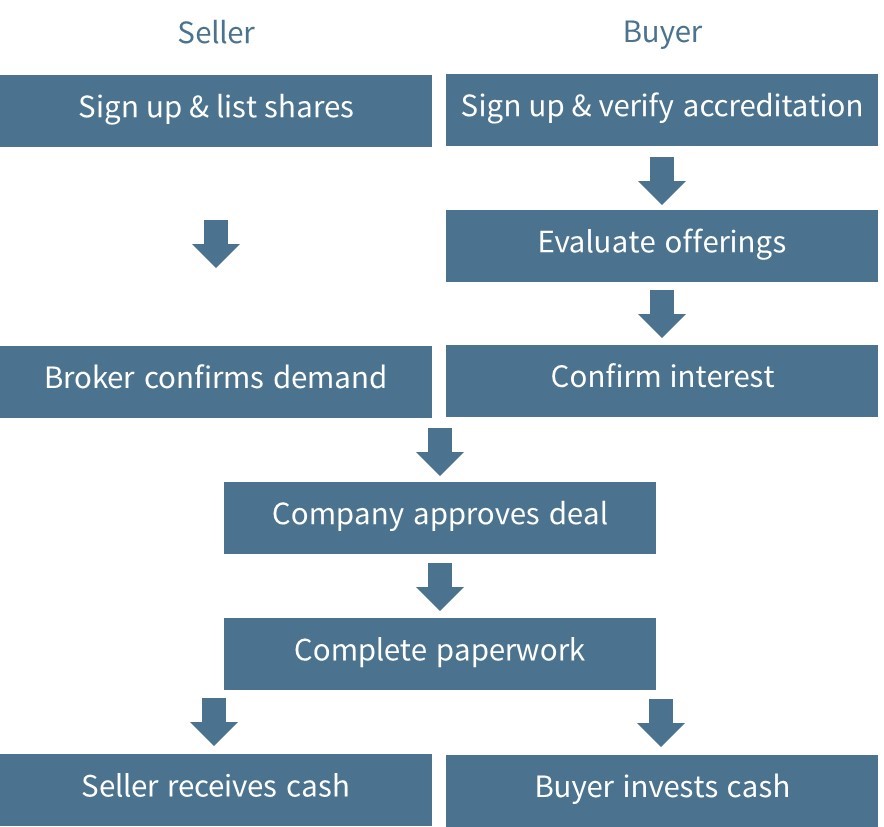

EquityZen. EquityZen sources deals from private companies and markets them at specific price offerings to investors through their website and email marketing. Sellers (individuals or a pool) register to offer securities (minimum of $150,000 required per security), and accredited buyers browse offerings (minimum commitment size of $20,000). EquityZen acts as broker in arranging transactions and charges commissions of 3 to 5 percent that depend on the size of the transaction. After buyers are identified, EquityZen contacts the company for approval and, if approved, the transaction is processed and settled (see Exhibit 1). EquityZen has closed over 4,750 transactions since 2013.

Exhibit 1: Private-Company Marketplace Transaction Process

Source: Adapted from EquityZen.

NASDAQ Private Market. NASDAQ Private Market is a software-as-a-service (SaaS) company that provides transaction software to private companies for structured sales programs, in which a private company coordinates the sale of shares for its employees and investors. Structured sales programs allow a company to impose guidelines, limitations, or restrictions around the sale of stock, approve individual transactions if necessary, and determine the price-setting mechanism (fixed-price tender, negotiated, or Dutch Auction). In 2017, NASDAQ Private Market arranged $3.2 billion in private transactions through 51 company programs. It has arranged over 15,350 individual transactions since initiating the structured sales program in 2013. Approximately three-quarters of sellers are current employees.

Securities sold through these marketplaces are not registered with the SEC and are not subject to its regulations and protections (apart from anti-fraud protections). In particular, companies whose securities are not registered are not required to comply with the comprehensive financial reporting and disclosure regulations that govern publicly traded companies.

Impact on Companies and Employees

From the standpoint of a company, allowing employees to sell some or all of their vested equity awards through private-company marketplaces offers both benefits and risks. The illiquidity of significant sums of money can put a potential hardship on employees, which are amplified if the employee had expected the company to complete an IPO in a shorter timeframe. Employees who anticipated being able to realize value from vested equity awards to fund major life events—such as the purchase of a home, marriage, or the raising of children—might be compelled to change jobs in order to fund these events. Allowing employees to sell a portion of their vested awards might be required for retention. It might also reduce pressure on companies to complete an IPO.

At the same time, employees who sell equity awards in private-company securities that are not registered with the SEC might not get a “fair” price for their investment, based on previous funding valuations or what they would get through an IPO or acquisition. The illiquidity risk of owning these securities transfers to any new owner, who would likely require a discount in the purchase price as compensation. Brokerage commissions and transaction fees further reduce the net proceeds of a sale.

Perhaps more important for the company is that allowing the sale of vested equity awards potentially distorts employee incentives. In structuring their compensation programs, companies decide on the correct mix of cash and equity to attract, retain, and motivate employees to pursue company objectives. An employee who is allowed to sell vested equity awards is effectively being allowed to convert variable, performance-based pay to a fixed amount of cash, significantly reducing (and distorting) the future incentive value of the compensation program.

Employee Equity Sales Practices at Private Companies

To understand how private companies manage these issues, we surveyed 34 companies predominantly in technology and services-related industries. [1]

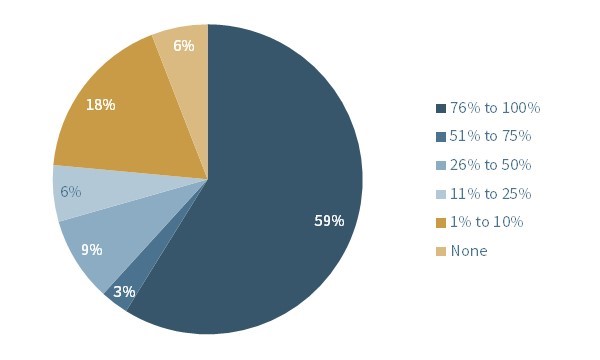

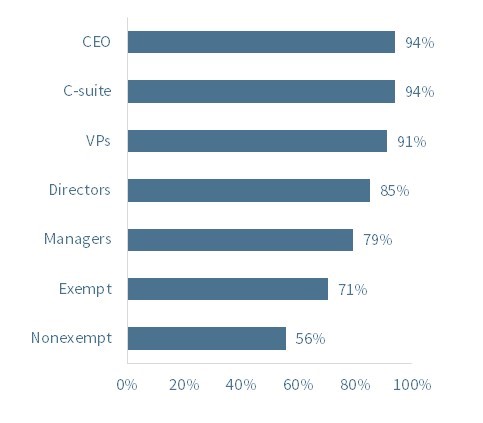

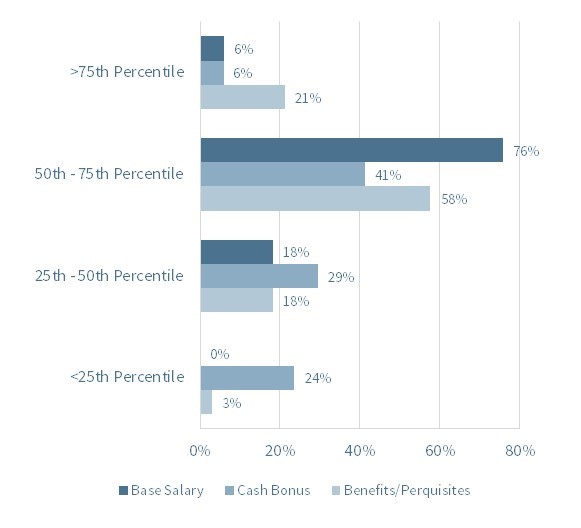

The practice of granting equity-based compensation is common among the private companies in our sample. The majority of companies grant equity-based awards to a large percentage of their employee base, spread widely throughout the organization. Furthermore, these awards are an important part of their overall compensation program and are intended to provide the majority of the incentive value of variable pay (see Exhibit 2 for details).

Exhibit 2: Private-Company Employee Stock Sales Practices: Descriptive Statistics

Approximately what percent of employees (including executives) in your company are granted stock-based compensation awards as part of their total compensation package?

What levels of employees are granted stock-based compensation awards in your company?

How do your non-equity compensation elements compare with market levels?

Are employees allowed to sell or pledge some or all of their vested equity holdings in the company?

When are employees or executives allowed to engage in these transactions?

When are these transactions allowed?

Who approves these transactions?

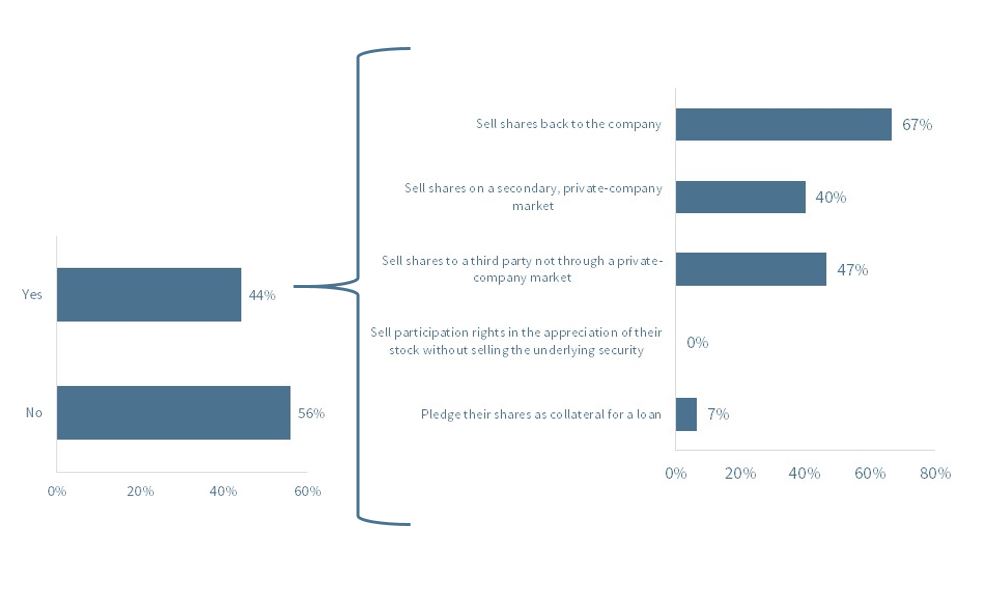

Perhaps, for this reason, companies are divided in terms of whether they allow employees to sell or pledge a portion of their vested equity awards. Just over half (56 percent) say they allow employees to sell or pledge their shares, while just under half (44 percent) do not allow this practice.

Among those that allow sales, two-thirds (67 percent) allow employees to sell shares back to the company, 40 percent allow them to sell shares on a secondary private-company marketplace like those described above, 47 percent allow them to sell to third parties not through a private-company exchange, and 7 percent allow them to pledge their shares as collateral for a loan. None of the companies in our sample allow employees to sell participation rights in the appreciation of their stock without selling the underlying security. Although we did not ask explicitly, many respondents specified that their company has right of first refusal on the shares.

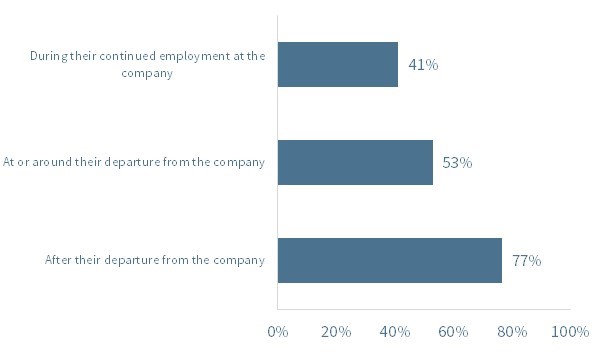

These companies also offer fairly wide leeway to employees in the timing of these sales. Forty-one percent allow employees to sell during the course of their continued employment; 53 percent allow sales at or around their departure from the company; and 77 percent allow employees to sell after departing. In addition, 40 percent allow employees to sell continuously at their own election, while 60 percent allow sales on an ad hoc basis, determined by the board.

Companies vary widely in terms of the limitations or restrictions they place on employee stock sales. Respondents mention a variety of restrictions, such as only allowing employees to sell 20 to 25 percent of their vested shares and only allowing sales after a minimum elapsed tenure of employment (3 or 4 years with the company). Some only allow stock sales at a change of control, termination of employment, or based on an evaluation of the individual employee’s contribution to the firm. One company charges employees a processing fee for shares sold to a third party because of the associated paperwork required of company officials.

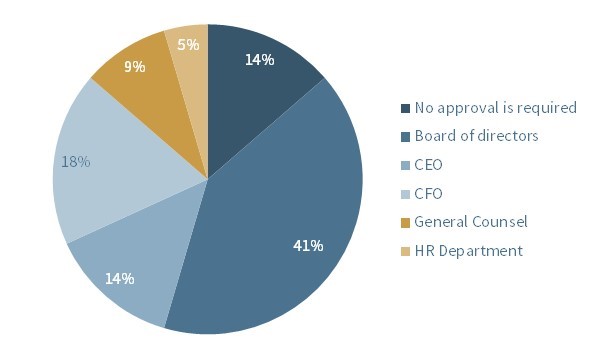

Employee stock sales are approved by the board of directors (41 percent of respondents), the CFO (18 percent), CEO (14 percent), general counsel (9 percent), or human resources department (5 percent). Fourteen percent do not require company approval.

Private-Company Marketplace Data

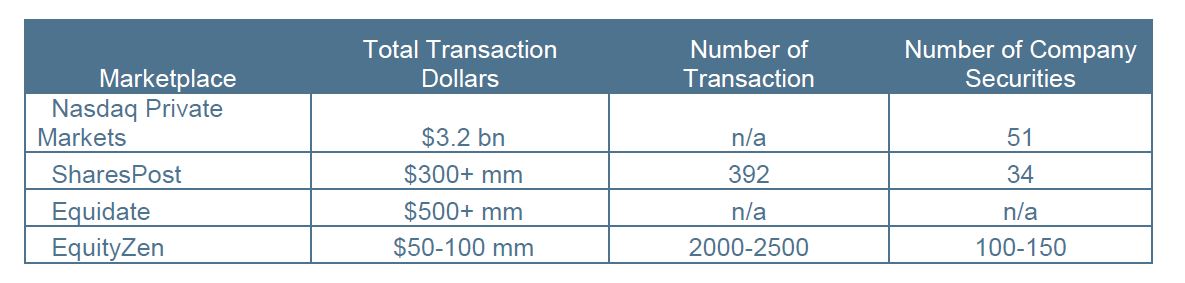

To consider the overall market size and the competitive landscape of private-company secondary markets, we collected 2017 transaction data from SharesPost, Equidate, EquityZen, and NASDAQ Private Market (see Exhibit 3). Two things become apparent in looking at these numbers. First, the overall size of the market is significant. Over $4 billion in transaction volume was executed by these four liquidity providers alone in 2017. Second, consistent with these firms serving different liquidity needs and clientele, there appears to be a large degree of variation in transaction volume and deal size. For instance, while NASDAQ Private Market aids in large scale liquidity programs, totaling approximately $3.2 billion, they only provided liquidity in 51 company securities. In contrast, EquityZen makes up a significantly smaller total dollar amount of transaction volume, at $50-100 million, but provided liquidity in approximately 100 to 150 company stocks in 2017. As this market matures, it is reasonable to expect the total market size and the number of players involved in the space to continue to grow.

Exhibit 3: Private-Company Marketplaces: Industry Volume (2017)

Sources: The companies.

Because many employees sell their shares through secondary, private-company marketplaces, it is interesting to consider the pricing that employees receive for their holdings. To do so, we received a sample of trading data from SharesPost. The sample includes $1.1 billion in transaction volume, comprising 130 private companies over the six-year period 2011-2016 (see Exhibit 4). [2]

Exhibit 4: Private-Company Marketplaces: Monthly Transaction Volume Data (SharesPost)

Sample includes $1.1 billion in transaction volume for shares of 130 private companies between 2011 and 2016. Note: Facebook completed its IPO in May 2012.

Source: SharesPost.

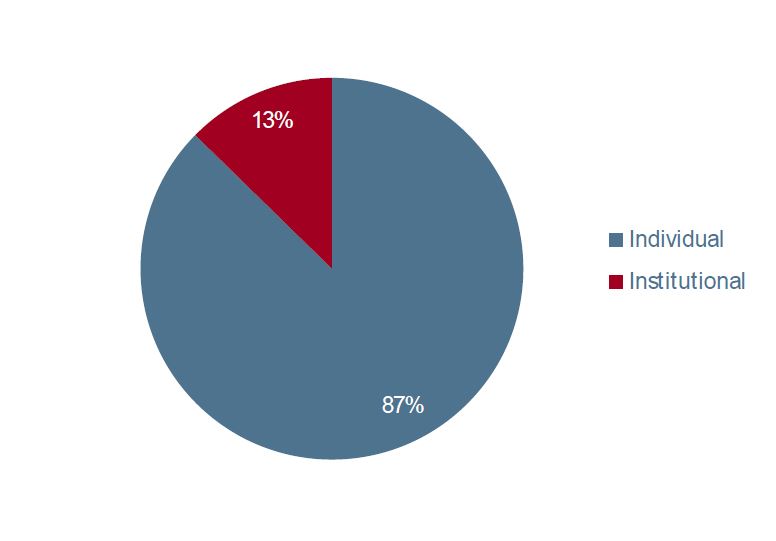

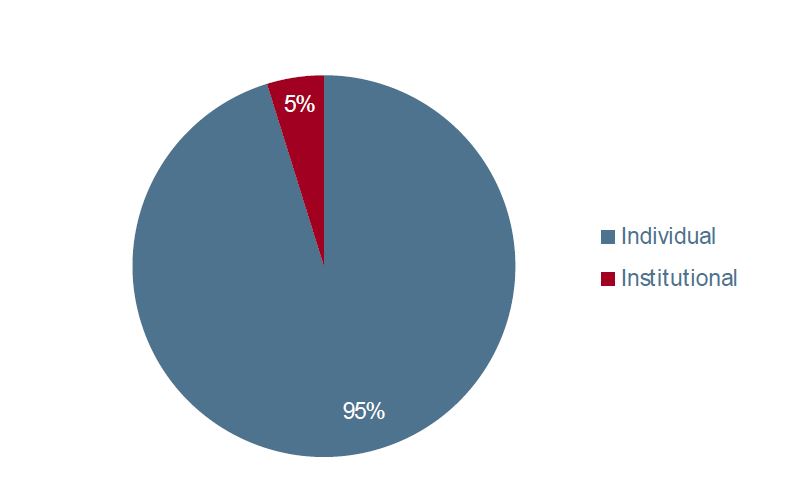

Individuals make up the largest portion of both the buyer and seller populations in our sample. [3] Individuals comprise 87 percent of the known-seller population, based on total transaction dollar amounts; institutions only 13 percent. Individuals comprise an even larger portion (95 percent) of the known-seller population based on number of transactions. The average individual transaction size is surprisingly large: $254,000. The average institutional transaction size is $731,000 (see Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5: Private-Company Marketplaces: Seller Information (SharesPost)

Known Seller Distribution—By Transaction Dollar Size

Known Seller Distribution—By Number of Transactions

Note: Known seller population excludes sellers whose status as an individual or institution is unspecified. Sample includes $1.1 billion in transaction volume for shares of 130 private companies between 2011 and 2016.

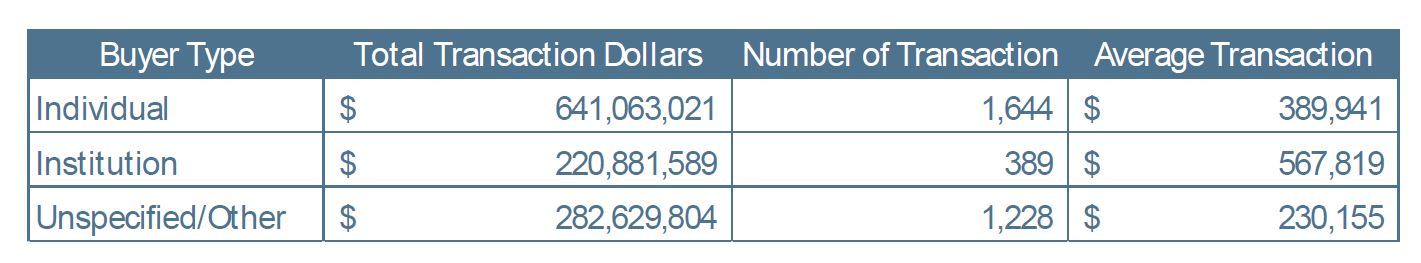

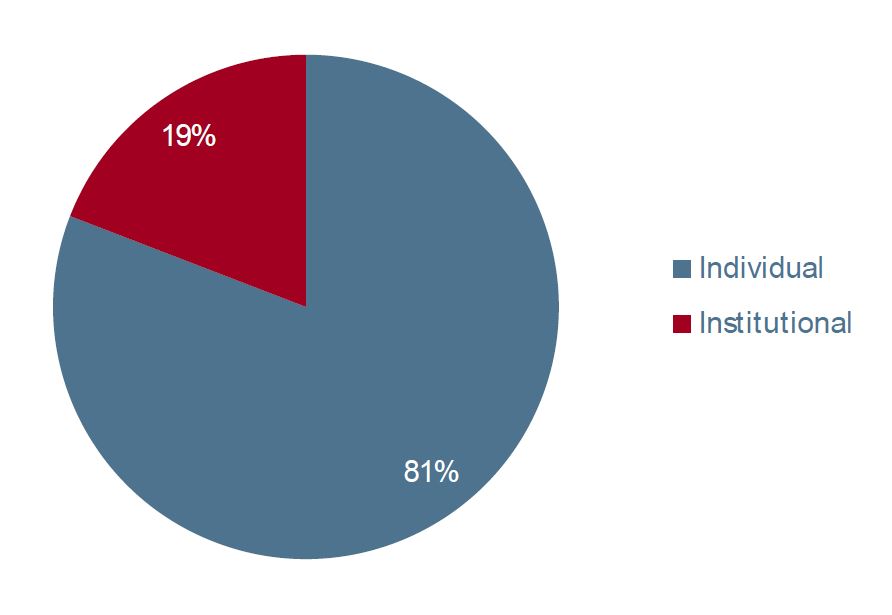

The known-buyer population is similarly distributed, although somewhat less skewed toward individual investors. Seventy-four percent of known buyers are individuals, based on transaction dollar amounts; 26 percent are institutions (see Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6: Private-Company Marketplaces: Buyer Information (SharesPost)

Known Buyer Distribution—By Transaction Dollar Size

Known Buyer Distribution—By Number of Transactions

Note: Known buyer population excludes buyers whose status as an individual or institution is

unspecified. Sample includes $1.1 billion in transaction volume for shares of 130 private companies between 2011 and 2016.

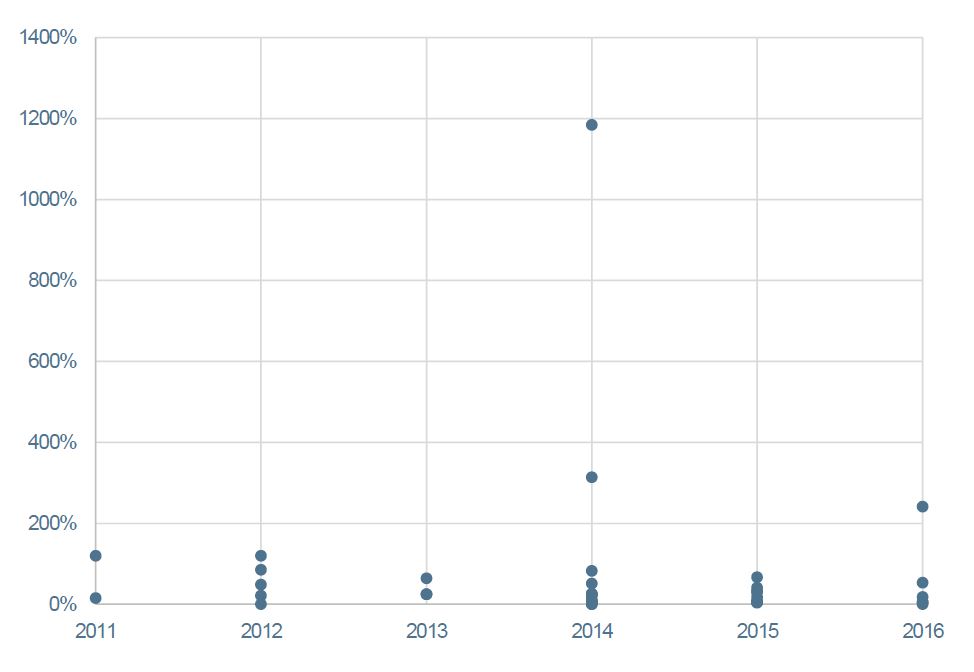

Prices are fairly volatile but not significantly more so than similar company prices on public exchanges. The average (median) spread between the high and low price for a subsample of “well-known” individual companies is 70 percent (23 percent—see Exhibit 7).

Exhibit 7: Private-Company Marketplaces: Price Change Data (Max Annual Price Over Minimum Price)

Subsample includes 40 unique company-years.

Source: SharesPost. Calculations by the author.

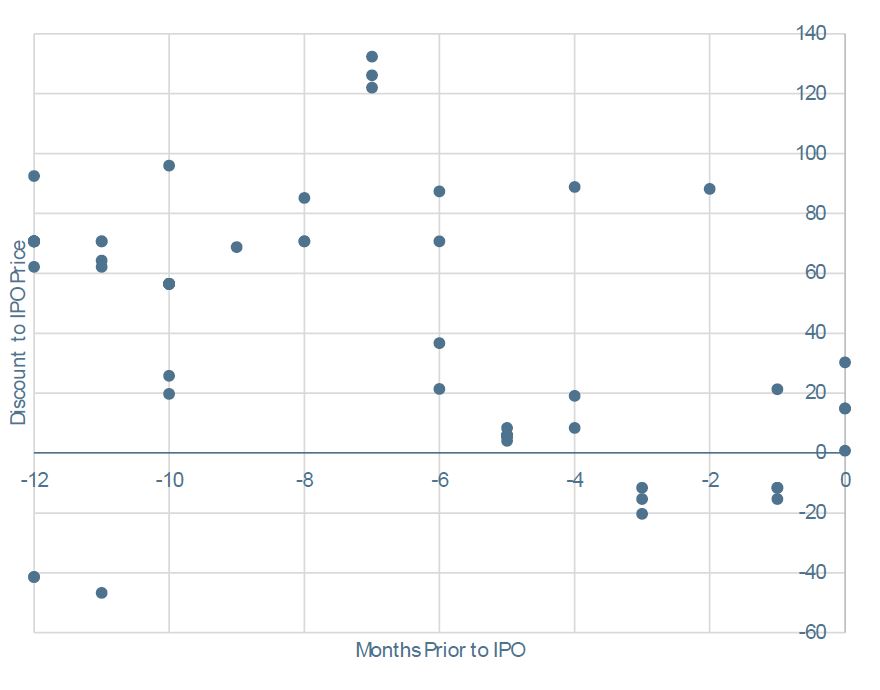

Finally, individual transaction data suggests that returns for investors in these markets can be substantial. Based on a subsample of companies that went public in the year following the transaction, the average (median) seller sold equity holdings at a 39 percent (47 percent) discount to subsequent IPO pricing (see Exhibit 8). [4]

Exhibit 8: Private-Company Marketplaces: Discount to IPO Pricing

Note: Based on pricing data of subsample of 58 transactions in the year prior to successful IPO. Positive values indicate that the investor sold shares as a discount to the subsequent IPO price; negative values indicate that the investor sold shares above the subsequent IPO price.

Source: SharesPost. Calculations by the authors.

The reasonableness of these discounts is subject to debate. On one hand, these discounts suggest that employees forfeit considerable value by selling prior to IPO. On the other hand, research studies offer some justification for significant discounts in illiquid securities. Studies have shown that when employees have restrictions on the ability to sell shares, they are willing to forgo substantial returns to diversify the risk of their personal wealth. Kahl, Liu, and Longstaff (2003) estimate that when a stock is restricted for five years and represents half of an individual’s personal wealth, the investor might gain (in terms of consumption needs and diversification) by selling stock for 30 to 80 percent of its unrestricted value. The authors note that discounts may be “significantly higher when nearly all of the entrepreneur’s wealth is tied up in restricted shares and when the entrepreneur is not able to hedge his restricted shares with offsetting stock market positions.” Similarly, studies show that buyers demand significant market discounts because of illiquidity, poor information, and the inherent riskiness of the companies trading in pre-IPO markets.

Why This Matters

- Companies use equity awards to attract, retain, and motivate high-performing and risk-seeking employees who work to increase firm value. However, when companies stay private longer, the incentive value of those awards can change as employees are left holding a large and illiquid investment that they cannot monetize or diversify.

- Should private companies allow employees to monetize a portion of their equity awards prior to an IPO or liquidity event?

- If so, what restrictions should they consider to ensure that the performance-value of the overall compensation program is not reduced?

- Should all employees be allowed to participate, or only employees above or below a certain level?

- Who within the company—the board or senior management—should determine the timing, scope, and terms of a sales program?

- Secondary private-company exchanges exist to facilitate transactions between private-company investors who want to sell their holdings and outside investors who want exposure to potentially attractive investments in pre-IPO companies. Securities sold through these marketplaces are not registered with the SEC and are not required to comply with its disclosure practices. Furthermore, pricing data suggests that some employees and inside investors sacrifice a significant amount of “upside” by selling shares at a large discount to subsequent IPO pricing.

- Would this discount be reduced (therefore benefiting employees) if the SEC took steps to boost the size and liquidity of these markets ? Or would doing so discourage more companies from going public by providing a more attractive (less regulated) means of providing liquidity to employees and inside investors?

- Does the growth of these markets suggest that the regulatory requirements of public exchanges have become too burdensome?

- Do private-company exchanges allow companies to stay private longer? If so, what impact does this have on investor returns and the distribution of wealth between private-company investors and public company investors?

Endnotes

1Sample includes 34 private companies with an average (median) founding date of 2003 (2004). Nine percent have revenue below $50 million, 24 percent between $50 and $100 million, 61 percent between $100 and $500 million, and 6 percent over $500 million. Six percent of the individuals responding to the survey are the founder of the company, 24 percent CEO or president, 38 percent CFO, 21 percent general counsel, 12 percent human resources or other officer. Forty-one percent of the companies in the sample are venture-capital funded, 32 percent private-equity funded, 9 percent a mix of VC and private equity funded, and 18 percent funded by other private owners. The survey was conducted between April and June 2018.(go back)

2Individual transaction data was anonymized so that no private information could be used to determine the identify of either party in the transaction. No compensation was paid to or received from SharesPost in the course of this study. The authors would like to thank SharesPost for making a sample of data available for research purposes.(go back)

3We did not have information to determine whether individual sellers were employees or other individual investors (such as angel investors).(go back)

4Note this subsample is inherently biased as it only includes returns for companies that successfully completed an initial public offering.(go back)

Print

Print