Timothy M. Doyle is Vice President of Policy & General Counsel at the American Council for Capital Formation (ACCF). This post is based on an ACCF memorandum by Mr. Doyle.

New research from the American Council for Capital Formation identifies a troubling number of assets mangers that are automatically voting in alignment with proxy advisor recommendations, in a practice known as “robo-voting.” This trend has helped facilitate a situation in which proxy firms are able to operate as quasi-regulators of America’s public companies, despite lacking any statutory authority.

While some of the largest institutional investors expend significant resources to evaluate both management and shareholder proposals, many others fail to conduct proper oversight of their proxy voting decisions, instead outsourcing decisions to proxy advisors. We reviewed those asset managers that historically vote in line with the largest proxy firm, Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), finding 175 entities, representing more than $5 trillion in assets under management, that follow the advisory firm over 95% of the time.

Proxy advisors regularly assert that their recommendations are only intended to be a supplemental tool used in voting decisions, yet too many asset managers fail to evaluate company specific considerations. Robo-voting is more concerning given recent concerns over the accuracy of advisor recommendations, the limited amount of time proxy advisors allow for company corrections, and the need for investment managers to align voting with fiduciary considerations, collectively highlighted in our previous study, Are Proxy Advisors Really A Problem? (discussed on the Forum here).

This new report, “The Realities of Robo-Voting,” quantifies the depth of influence that proxy advisory firms control over the market and identifies asset managers that strictly vote in alignment with advisor recommendations. Significantly, the research finds that outsourced voting is a problem across different types of asset managers, including pension funds, private equity, and diversified financials. Further, size of assets under management appears to have little impact, as both large and small investment firms display near-identical alignment with advisor recommendations.

The lack of oversight of proxy advisors, who dictate as much as 25% of proxy voting outcomes, is increasingly becoming a real issue for investors and it must be addressed. This report offers additional analysis of the asset manager voting landscape and reiterates important questions regarding the influence, impact, and conflicts of proxy advisory firms.

Introduction

By 2017, approximately 70% of the outstanding shares in corporations in the United States were owned by institutional investors such as mutual funds, index funds, pension funds and hedge funds. Institutional investors have significantly higher voting participation (91%) than retail investors (29%) and the proliferation of institutional ownership has given these entities a disproportionately large influence over voting outcomes at annual shareholder meetings. The growing increase in institutional ownership has correspondingly increased the power and influence of proxy advisors. These firms provide a number of services related to proxy voting, including voting recommendations.

The single biggest catalyst for the rise in influence of proxy advisors was the 2003 decision by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) [1] to require every mutual fund and its investment adviser to disclose “the policies and procedures that [they use] to determine how to vote proxies”—and to disclose their votes annually. While the intention of the SEC was to spur greater engagement with the proxy voting process from mutual funds, the decision has had the opposite effect. While some institutional advisors have internal analysts to develop and implement the required “policies and procedures,” many institutional investors have been disincentivized to carry out their own independent evaluations of proxy votes and governance practices, outsourcing their shareholder voting policies to a proxy advisor industry that relies on a “one size fits all” approach to assessing corporate governance. This issue may be best seen through the practice of ‘robo-voting’, whereby institutions automatically and without evaluation rely on proxy firms’ recommendations, posing lasting implications for corporate policy, returns, and governance outcomes.

A Growing Influence in Robo-Voting

Originally explained in ACCF’s prior paper The Conflicted Role of Proxy Advisors, robo-voting is the practice of institutions automatically relying on both proxy advisors’ recommendations and in-house policies without evaluating the merits of the recommendations or the analysis underpinning them.

The influence of proxy advisors continues to grow as more and more institutional advisors follow their recommendations. In fact, academic studies continue to point to the influence of the two major proxy advisors—ISS and Glass Lewis—on voting outcomes. The level of influence of ISS is estimated as being between 6-11% [2] and up to 25%. [3]

ISS, aided by the lack of transparency over how its policies are formulated and how its recommendations are arrived at, denies the full scope of its influence, instead alluding to its role as an “independent provider of data.” In a response to the Senate Banking Committee in May 2018, ISS claims:

“We do, however, want to draw a distinction between our market leadership and your assertion that we influence ‘shareholder voting practices.’ ISS clients control both their voting policies and their vote decisions… In fact, ISS is relied upon by our clients to assist them in fulfilling their own fiduciary responsibilities regarding proxy voting and to inform them as they make their proxy voting decisions. These clients understand that their duty to vote proxies in their clients’ or beneficiaries’ best interests cannot be waived or delegated to another party. Proxy advisors’ research and vote recommendations are often just one source of information used in arriving at institutions’ voting decisions… Said more simply, we are an independent provider of data, analytics and voting recommendations to support our clients in their own decision-making.”

—Institutional Shareholder Services, May 2018

Likewise, Glass Lewis offered an explanation for the “misperception” that it exerts influence on shareholders:

“Glass Lewis does not exert undue influence on investors. This is clearly evidenced by the fact that during the 2017 proxy season Glass Lewis recommended voting FOR 92% of the proposals it analyzed from the U.S. issuer meetings it covers (the board and management of these companies recommended voting FOR 98% of the same) and yet, as noted by ACCF sponsor Ernst & Young, directors received majority FOR votes 99.9% of the time and say-on-pay proposals received majority FOR votes 99.1% of the time…The market is clearly working as shareholders are voting independently of both Glass Lewis and company management.”

—Glass Lewis, June 2018

Undoubtedly, certain large institutional investors use proxy advisor recommendations and analysis as an information tool, employing multiple advisors in addition to their own in-house research teams in an effort to ensure they have a balanced view of how best to vote on a particular proxy item. As previously highlighted in a report by Frank Placenti, chair of the Squire Patton Boggs’ Corporate Governance & Securities Regulation Practice, BlackRock’s July 2018 report on the Investment Stewardship Ecosystem states that while it expends significant resources evaluating both management and shareholder proposals, many other investor managers instead rely “heavily” on the recommendations of proxy advisors to determine their votes, and that proxy advisors can have “significant influence over the outcome of both management and shareholder proposals.” [4]

In looking at asset managers more broadly, many entities have fewer resources to process the hundreds of proposals submitted each year, and in turn are left to not only utilize proxy advisory data, but automatically vote in line with their recommendations. ISS asserts they are not influential, stating they are instead an “independent provider of data, analytics and voting recommendations to support our clients in their own decision-making.” The voting results, compared to their recommendations, are in direct conflict with ISS’s public views on the role it plays in the proxy process.

Therefore, in stark contrast to the misinformation provided to the Senate Banking Committee by ISS, ACCF’s new research demonstrates that ISS’s role is much more than that of an information agent. The reality is clear: hundreds of firms representing trillions of assets under management are voting their shares almost exactly in line with proxy advisors’ recommendations. Given the sheer numbers, the argument of independent data provider and mere coincidence on the actual voting is implausible.

How Can We Be Sure Robo-Voting Happens and Which Types of Institutional Investors Are Doing It?

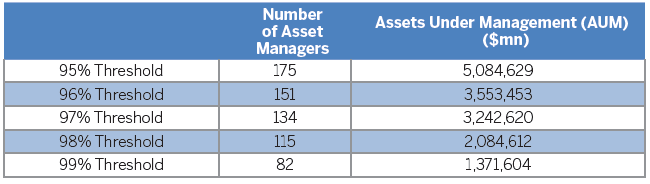

ACCF conducted a detailed analysis of Proxy Insight data and evaluated those asset managers that historically voted in line with ISS recommendations. Specifically, the evaluation sought to identify those managers that aligned with ISS recommendations more than 95% of the time on both shareholder and management proposals. The analysis found that 175 asset managers with more than $5 trillion in assets under management have historically voted with ISS on both management and shareholder proposals more than 95% of the time. [5]

There may be those that say 95% is a justifiable alignment—after all, many matters on which institutions are asked to vote are matter-of-fact issues on ordinary course business operations. However, in the analysis we also assessed different robo-voting thresholds.

Upon increasing the threshold for robo-voting, the list of asset managers shrinks only marginally at each level. Of the 175 asset managers in the 95th percentile, nearly half are in the 99th percentile. That is, they are voting with ISS on both management and shareholder proposals more than 99% of the time. In sum, regardless of how one defines robo-voting—be it at 95% alignment or 99%—the data shows it is more than a coincidence that the practice is happening and equally important that it broadly represents a significant proportion of investment dollars.

Which Institutions are Implementing this Strategy?

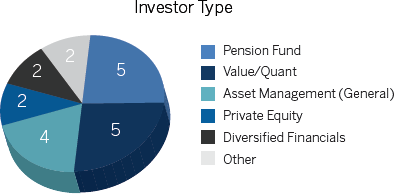

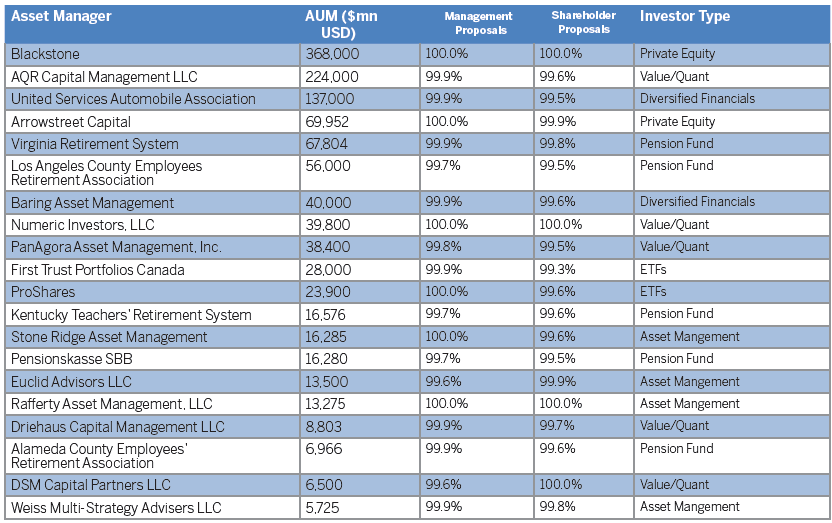

The list below identifies the top 20 robo-voters by AUM in the highest threshold category (99%). [6] Interestingly, previous assumptions were that this list would largely comprise quantitative hedge funds; however, the type of investor that almost never deviates from an ISS recommendation is far more diverse: Indeed, when broken down by investor type, the picture of the entities who almost never deviate from an ISS recommendation is split across several categories and topped by pension funds and value and quant funds.

Indeed, when broken down by investor type, the picture of the entities who almost never deviate from an ISS recommendation is split across several categories and topped by pension funds and value and quant funds.

The reliance on proxy advisors is not just limited to investors where proxy voting may be viewed as a compliance function rather than an added value. Robo-voting is widespread: it is prevalent at a range of investor-types, and at large and small investors.

It is perhaps unsurprising that such significant levels of robo-voting occur in the proxy voting process. Both major proxy advisors derive the majority of their work not from their research, but from the provision of voting services, that is, providing the mechanics through which institutions vote their shares and comply with SEC regulations. As ACCF has explored previously, proxy advisory firms are, by design, incentivized to align with the comments of those who use their services the most. Moreover, many votes are cast through electronic ballots with default mechanisms that must be manually overridden for the investor to vote differently than the advisor recommends. [7]

While certain major institutions have the resources to put in place internal proxy voting processes, for the majority of institutions the requirement to vote represents a significant cost burden. For those entities, ISS and Glass Lewis provide a cost-efficient way of voting at thousands of meetings each year; [8] however, the negative externality is that some institutional investors do not have the capacity or the interest to review the research associated with the voting of their shares. Instead, they simply allow their shares to be voted through the proxy advisors’ platforms and according to the proxy advisors’ methodologies.

Why Does it Matter?

Fundamentally, in 2003, the SEC recognized proxy voting was an important aspect of the effective functioning of capital markets. However, under the current system, corporate directors and executives are subject to decision making on critical issues by entities that have no direct stake in the performance of their companies; have no fiduciary duty to ultimate beneficial owners of the clients they represent; and provide no insight into whether their decisions are materially related to shareholder value creation. Informed shareholders, who have such a stake and carry out their own independent research, suffer due to the prevalence of robo-voting, because their votes are overwhelmed by these same organizations.

The practice of robo-voting can also have lasting implications for capital allocation decisions and has resulted in ISS and Glass Lewis playing the role of quasi-regulator, whereby boards feel compelled to make decisions in line with proxy advisors’ policies due to their impact on voting.

While limited legal disclosures are actually required, a proxy advisory recommendation drawn from an unaudited disclosure can in many cases create a new requirement for companies—one that adds cost and burden beyond existing securities disclosures.

In addition, a recent ACCF commissioned report, ‘Are Proxy Advisers Really a Problem?’, led by Squire Patton Boggs’ Placenti, discusses the pertinence of factually or analytically flawed recommendations and the limited time provided to companies to respond to errors. Based on a survey by four major U.S. law firms of 100 companies’ experiences in the 2016 and 2017 proxy seasons, respondents reported almost 20% of votes are cast within three days of an adverse recommendation, suggesting that many asset managers automatically follow proxy advisory firms. The report also includes an assessment of supplemental proxy filings, an issuer’s main recourse to a faulty recommendation. Based on a review of filings from 94 different companies from 2016 through September 30, 2018, the paper identifies 139 significant problems, including 49 that were classified as ‘serious disputes.’ In turn, errors in recommendations are magnified by the practice of automatic voting by select asset managers.

An error by a proxy advisor can have a material impact on voting as a host of proxy advisor clients will not review the research that contains the error, and will instead merely vote in line with the recommendations provided. As a result, when shareholders blindly follow an erroneous recommendation from a proxy advisor, their mistakes are perfectly correlated, [9] which can have real and damaging impacts on public companies.

Furthermore, institutions that do not research these proposals are negligently relying on proxy advisors to ensure their vote aligns with their clients’ best interests. Yet proxy advisors have no fiduciary duty to the ultimate beneficiaries of mutual funds and have provided no evidence that their analysis and recommendations are linked to the protection or enhancement of shareholder value. [10] The fiduciary duty owed to investors has always been at the center of this debate. As former SEC Commissioner Daniel Gallagher indicated back in 2013:

“I have grave concerns as to whether investment advisers are indeed truly fulfilling their fiduciary duties when they rely on and follow recommendations from proxy advisory firms. Rote reliance by investment advisers on advice by proxy advisory firms in lieu of performing their own due diligence with respect to proxy votes hardly seems like an effective way of fulfilling their fiduciary duties and furthering their clients’ interests. The fiduciary duty…must demand more than that. The last thing we should want is for investment advisers to adopt a mindset that leads to them blindly cast their clients’ votes in line with a proxy advisor’s recommendations, especially given that such recommendations are often not tailored to a fund’s unique strategy or investment goals.” [11]

As explored in ACCF’s previous report, “While it is not the intention of SEC policy and may be a violation of fiduciary duties and ERISA, the reality of robo-voting is real.” [12] The result: enhanced power of proxy advisory firms with a potential for adverse recommendations and company outcomes, and limited ability for targeted companies to engage with their own diverse shareholder base. Regardless of whether one considers the role of proxy advisors to be positive or negative, it is clear the influence of ISS is not overstated.

Conclusion

It seems out of sync with effectively functioning capital markets that proxy advisory firms remain unregulated, despite essentially representing trillions of assets at the annual shareholders meetings of U.S. corporations. By wielding the aggregated influence of those investors that blindly follow their recommendations, proxy advisors possess the ability to drive change in corporate behavior and practices, without being required to provide any meaningful transparency over how their decisions are made. Through the research on robo-voting, it’s abundantly clear that proxy advisors have an indisputable influence over shareholder voting.

Robo-voting enhances the influence of proxy advisory firms, undermines the fiduciary duty owed to investors; and poses significant threats to both the day-to-day management and long-term strategic planning of public companies. In keeping with the regulation of mutual funds, who individually possess significantly less influence than proxy advisors, it seems natural that the proxy advisors would be subject to similar regulatory requirements and oversight. Greater exploration of the extent of this practice provides an opportunity to support the upcoming SEC Roundtable on the Proxy Process, where the commission will be looking for additional detail regarding the influence, impact, and bias of proxy advisory firms.

Endnotes

1SEC, “Securities and Exchange Commission Requires Proxy Voting Policies, Disclosure by Investment Companies and Investment Advisers,” press release, January 1, 2003, available at: http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2003-12.htm(go back)

2Choi, Stephen; Fisch, Jill E.; and Kahan, Marcel, “The Power of Proxy Advisors: Myth or Reality?” (2010). Faculty Scholarship. 331(go back)

3Nadya Malenko, Yao Shen; The Role of Proxy Advisory Firms: Evidence from a Regression-Discontinuity Design, The Review of Financial Studies, Volume 29, Issue 12, 1 December 2016, Pages 3394–3427(go back)

4Available at: https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/whitepaper/viewpoint-investment-stewardship-ecosystem-july-2018.pdf(go back)

5All Proxy Insight data was pulled from the platform as of October 13, 2018 and was filtered to include only those funds that had voted on more than 100 resolutions. ISS alignment data on the platform reflects all data available for each investor, which generally dates back as early as July 1, 2012 through the date it was pulled.(go back)

6AUM data drawn from Proxy Insight reported data, except in a few select cases where Proxy Insight data was unavailable and was augmented by IPREO data as of August 1, 2018. Voting alignment percentages are rounded to the nearest tenth.(go back)

7This robo-voting procedure was described in detail in the August 3, 2017 letter of the National Investor Relations Institute to SEC Chair Jay Clayton, available at: https://www.niri.org/NIRI/media/NIRI-Resources/NIRI-SEC-Letter-PA-Firms-August-2017.pdf(go back)

8ISS provides proxy voting to clients through its platform: ProxyExchange. Glass Lewis provides proxy voting through its platform: Viewpoint.(go back)

9Andrey Malenko and Nadya Malenko, The Economics of Selling Information to Voters, J. FIN. (forthcoming) (June 2018), available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2757597(go back)

10In a number of papers, researchers have found that ISS’s recommendations negatively impact shareholder value: David F. Larcker, Allan L. McCall, and Gaizka Ormazabal, “The Economic Consequences of Proxy Advisor Say-on-Pay Voting Policy” (Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University Working Paper No. 119, Stanford, CA, 2012), available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2101453. David Larcker, “Do ISS Voting Recommendations Create Shareholder Value?” (Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University, Closer Look Series: Topics, Issues and Controversies in Corporate Governance and Leadership No. CGRP-13, Stanford, CA, April 19, 2011): 2, available at: http://papers.ssrn .com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1816543.(go back)

11Commissioner Daniel M Gallagher, Remarks at Georgetown University’s Center for Financial Markets and Policy Event Securities and Exchange Commission Speech (2013), available at: https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/2013-spch103013dmg(go back)

12Available at: http://cdn.accf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/ACCF-The-Conflicted-Role-of-Proxy-Advisor-FINAL.pdf (page 24) (accessed October 12, 2018)(go back)

Print

Print