Sarah Williamson is the Chief Executive Officer of FCLTGlobal. This post is based on a FCLTGlobal memorandum by Ms. Williamson, Steve Boxer, Victoria Tellez, and Josh Zoffer. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Myth that Insulating Boards Serves Long-Term Value by Lucian Bebchuk (discussed on the Forum here); The Uneasy Case for Favoring Long-Term Shareholders by Jesse Fried (discussed on the Forum here); and Can We Do Better by Ordinary Investors? A Pragmatic Reaction to the Dueling Ideological Mythologists of Corporate Law by Leo E. Strine (discussed on the Forum here).

By some accounts, public markets are out of fashion. Detractors point to the decline of IPOs in developed economies and the growth of private capital pools over the last few years. But these trends tell only one side of the story. Private markets are doing well, but their success does not suggest the decline of public markets. Public markets continue to be an essential driver of wealth creation, innovation, and capital stability for high-performing companies. Despite the short-term pressures of public markets, the best-managed companies can and do take advantage of the benefits public markets have to offer. For companies playing at the highest level, public markets remain an integral element of their long-term growth.

During the 20th century, public markets were the indisputable core of economic dynamism in developed markets. The great companies of that period—BP, Ford, General Electric, IBM, Sony, Toyota, and the like—were more than just household names. They were sources of innovation, growth, and jobs powered by public markets. Their success was reflected in soaring stock markets that illustrated the link between their long-term success and broader economic health. That connection went both ways—these companies also relied on public markets for the capital driving their growth and prosperity.

Today, some suggest that public markets have lost their luster. Private capital stands at record levels, including uncommitted “dry powder” that indicates the global oversupply of such funds. More notably for public markets’ detractors, the success of venture capital-funded unicorns (those with valuations over $1 billion) suggests to some that public markets are an anachronism. If Uber, Airbnb, and the like can make a go of it without the rigorous discipline of public market funding, why should anyone else? If anything, they say, the era of public markets is over.

This sentiment is profoundly misguided—unicorns are the exceptions that prove the rule. A closer look at the data suggests that for large companies driving the greatest share of wealth and job creation, public markets are essential. First, large-cap IPO activity and overall public market capitalization remain robust. Although smaller companies rely more on private capital than before, the biggest players, even in capital-light businesses, continue to turn to public markets for the capital they need to thrive. Second, the evidence points to clear reasons for the continued vibrancy of public markets for large firms. Public markets drive the majority of wealth creation for the most successful companies, offer superior opportunities for employees and savers to share in these gains, and lower companies’ cost of capital relative to private markets. To paraphrase Mark Twain, rumors of the death of public markets have been greatly exaggerated. Businessweek infamously declared the death of public equity markets on its cover in 1979. That claim proved just as premature then as it does today.

What does this mean for companies that seek to take advantage of these benefits but resist the short-term pressures that public markets can bring? By targeting the right shareholders with a long-term mindset, building a focused board that will support long-term growth, and retaining their pre-IPO “ownership mindset,” companies can reap the benefits of public listing while avoiding its pitfalls. By employing these tools, public markets can and will remain an indispensable element of long-term growth for the most successful companies.

Public Markets are Alive and Well

On the surface, it is easy to identify the sources of doubts about public markets: IPOs in developed markets are down and private assets are up. But dig beneath the surface and the picture changes dramatically. These trends mask the real story: although smaller companies have become more reliant on private capital, public markets remain the focal point of capital raising and growth for large, economically significant companies. Private debt, in particular, has also become a significant factor in funding private companies.

What’s really going on with listing and IPOs

Skeptics of public markets are not wrong when they say IPOs and the number of publicly-listed companies are in decline. The number of US publicly-listed companies has steadily declined over the past 20 years, from just over 7,400 in 1997 to about 3,600 today. Even more strikingly, this number is well below the number of US listings in 1975. Today, well-known indices have had trouble living up to their names. The Wilshire 5000, for example, only has about 3,700 constituents due to delisting. The same trend holds true for IPOs. US IPOs have fallen from 706 in 1996 to just 160 in 2017.

Globally, that picture is somewhat rosier, especially in Asia. There were 1,700 listings worldwide in 2017, the most since the financial crisis. But there is no denying that—by listing numbers alone—developed country public markets appear more sparsely populated than in the recent past.

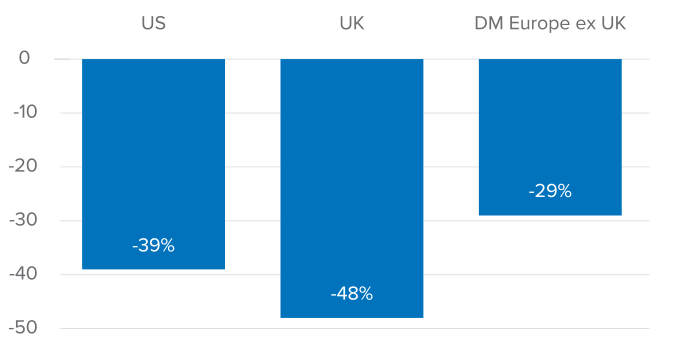

From 1993–2017, the number of listed companies within has fallen precipitously across developed markets:

This result ought to be taken with a grain of salt, or several. Most importantly, the decline in IPOs and listed companies has been driven by slowdowns at the small end of the market. Small IPOs (those below $100 million) averaged 401 per year in the 1990s. That number has fallen to 105 since 2000. Mid-sized and large IPOs appear to vary cyclically and were hit hard by the financial crisis. Today, though, they have mostly recovered and are well in line with historical levels. Indeed, there have been more large-firm IPOs (>$100 million) than small firm IPOs in all but one year since 2003. Small companies may stay private longer, but the most economically significant companies continue to turn to public markets to meet their capital needs.

As Craig Doidge and his colleagues at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management have recently argued, although smaller firms have less need for public markets, it is undeniable that large firms that go public have continued to prosper. “The winners in public markets are doing very well indeed.”

Moreover, looking at the number of IPOs rather than public companies’ size and overall market capitalization obscures the enduring strength of public markets. A combination of fewer listings by small companies and ongoing M&A activity among large listed firms has left the average market capitalization of US public companies at more than $7 billion, higher than at any point since 1980.

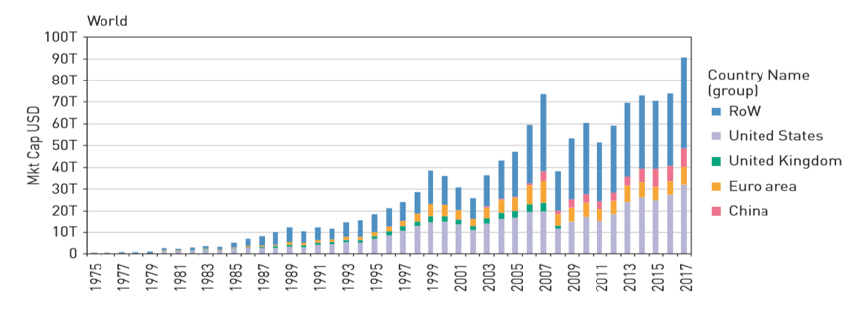

Market capitalization of listed companies by region (in USD):

Before declaring the death of public markets in the US, skeptics also might want to look at the role they play in the overall US economy—the “stock” rather than the “flow” of public markets, so to speak. By this measure, public markets are undoubtedly alive and well. According to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, the ratio of US stock market capitalization to GDP stands at over 150 percent, the highest level on record. Globally, as shown in the chart above, total public market capitalization stands at over $90 trillion, or about 112 percent of global GDP (compared to about 70 percent for China and 80 percent for the Euro area).

Irrespective of developed equity market worries, global equities markets are more geographically diverse than ever before. And they are continuing to grow.

Economically, public firms are indispensable. According to Brian Cheffins of the University of Cambridge, public firms account for half of US business capital spending, and the Fortune 500 alone are responsible for sales equivalent to 65 percent of US GDP.

Number of listed domestic companies and ratio of stock market cap to GDP:

Listing numbers alone only tell half the story. Public companies continue to form the foundation of the American economy and show little sign of abandoning that role. Moreover, this dubious story is inapplicable to equity markets in much of the world. China, Russia, Indonesia, and Korea, among others, have experienced significant growth in publicly listed companies over the last 25 years. In countries without fully developed public equities markets, growth remains robust. And although the flow of companies into public markets in developed economies has slowed, public markets remain healthy when measured against GDP.

The rise and role of private capital

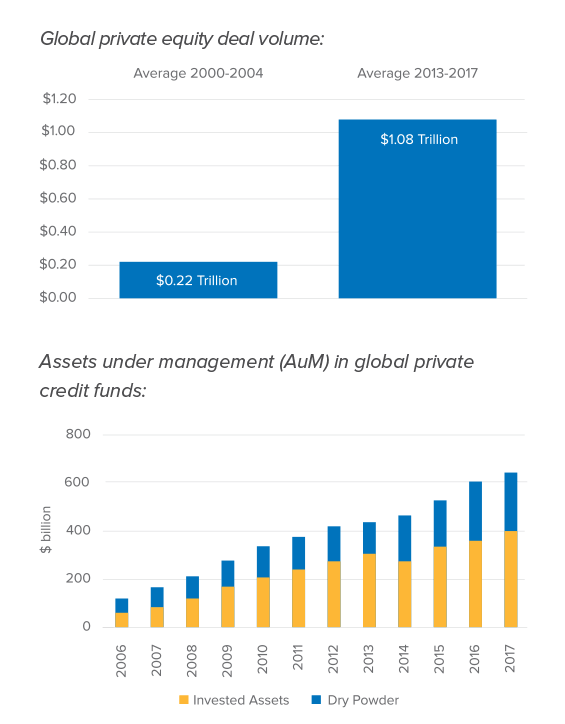

Public markets alone do not provide a complete picture. It is true that large pools of private capital as well as capital-light business models have lessened the need—at least for some companies—to turn to public markets to underwrite growth. Globally, private market assets under management (including private equity, venture capital, real estate, private debt, and infrastructure) stood at $5.2 trillion in 2017, the highest level on record. Of that total, traditional PE, VC, and growth capital accounted for $2.7 trillion. And the availability of private capital shows no signs of slowing. Private capital fundraising hit nearly $750 billion in 2017, higher even than its pre-crisis peak in 2007.

Deal volume, too, has continued to increase. 2017 saw $1.27 trillion in private equity deals globally, higher than any year on record other than 2007. And with $1.8 trillion of unused dry powder—another record—there is little reason to believe this will change.

Skeptics point to all this private capital as a harbinger of regime change in capital markets. Companies like Uber have increasingly turned to global private capital pools—including direct investment from large asset owners—to meet their capital needs while remaining private. There is no question that there is more private capital from more sources available than ever before. Why go public, some ask—with shareholders to please and regulatory requirements to meet—when there is more than enough private capital to keep your firm capitalized?

This has been the attitude of many privately-held unicorns (at least for now), with their billion-dollar-plus valuations. From 2014 to 2018, the number of US unicorns grew from 31 to 105. Globally, the number stands at more than 300 as of August 2018. With this track record and ample private funds ready to be deployed, some argue the need for capital from public markets has substantially diminished.

Although there is some truth to this view, upon closer examination the numbers do not bear out the claim the private markets are a true substitute for public markets, at least for the largest companies. Take the unicorns—the largest of the young private companies. Their average valuation is about $3.4 billion. The largest few are significantly larger than that, skewing the average; the median is closer to $1.5 billion. And remember, these are the largest and most successful of these companies. Most don’t come close to needing capital in the billions.

By contrast, the three largest publicly traded companies in the US—Apple, Alphabet, and Microsoft—are collectively larger than the entire global PE industry’s supply of dry powder. Private capital can sustain startups while they are young and small. That accounts for the decline of IPOs among smaller firms, which have been displaced by venture capital and other sources of private funds. But for those that want to achieve real scale, public markets still offer unparalleled depth and liquidity. Facebook, for example, essentially had to go public when it exceeded the SEC imposed limit on shareholders for non-reporting companies. Much of that result was driven by employees’ sales of stock—when companies are big enough and employees need liquidity, public markets are essentially the only game in town.

This intuition has been borne out as of late. Although they have long remained private, notable unicorns like Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Slack, and Palantir are all planning or rumored to be planning IPOs for 2019. According to the New York Times, experts “expect [ ] a wave of initial public offerings” among unicorns over the next 18 months. This revealed preference for (or at least interest in) public markets among the largest of the unicorns begs the question: with all that private capital, what is driving them to go public? The answer is that public markets offer something that private markets don’t, something that appeals to companies at the top of their game and the vanguard of their industries: wealth creation, low-cost and stable capital, and liquidity that cannot be found elsewhere.

Moreover, late-stage private companies are increasingly approaching large institutional investors for investment just prior to IPO. This gives them not only access to capital but to advice from experienced, public-markets-oriented investors who offer a perspective VCs cannot. The advice seems to work: technology firms that IPO with a pre-IPO mutual fund investor generate double the one-year post-IPO performance of firms without such investors. Even private capital investment can sometimes be a precursor to public listing.

Finally, the “death of public markets” narrative misses the significant number of companies that quietly enter public markets not by the front door of an IPO but by the back door: acquisition by a publicly-traded firm. According to Vanguard, more than 500 of these “phantom” public companies join the ranks of public markets each year through acquisitions. These phantom listings help explain why US stock market capitalization as a share of GDP is at an all-time high while IPOs are in decline.

Many of the world’s leading startup acquirers are large public firms. What’s more, many firms make a substantial number of acquisitions before going public. Twitter, for example, made 31 acquisitions prior to its IPO. Facebook made 29, among them Instagram, Oculus, and WhatsApp, all highly valued companies in their own right. When these acquirers eventually go public, they bring their acquisitions with them. And with worldwide startup acquisition deal volume at record levels, the role of acquisitions in bringing companies to public markets shows no signs of slowing, especially if the IPO trend among unicorns takes off.

There is more than one way to go public. When these backdoor listings are considered, the vitality of public markets becomes even clearer. Collectively, the evidence suggests public markets are not only healthy but remain the most attractive option for many large companies.

Public Markets Create and Spread Wealth

What is it, then, that is driving well-funded unicorns toward public markets? And why have large enterprises continued to rely on public markets? Three primary factors have driven public markets’ continued vitality: unparalleled wealth creation; opportunities for employees and savers; and stable, low-cost access to capital.

Unparalleled wealth creation

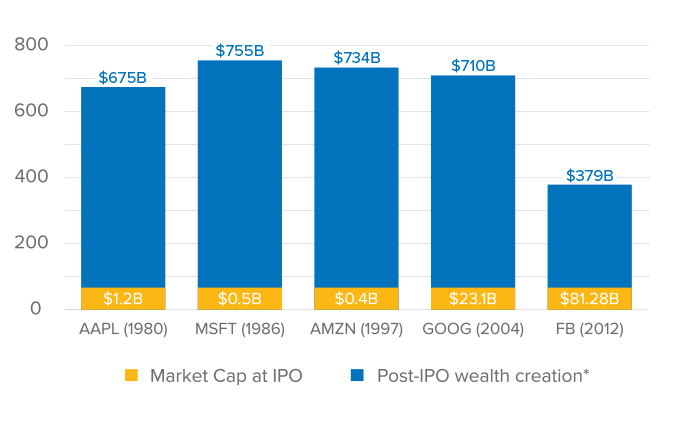

Whether it’s Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon in the 1980s and 1990s or Google and Facebook today, there is no denying that public markets have been integral to the wealth creation of many leading companies. Access to a larger, more liquid pool of capital has enabled leading companies to monetize their success and reach their full potential. Today’s unicorns find themselves turning to public markets for similar reasons.

“Now the time has come for the company to move to public ownership. This change will bring important benefits for our employees, for our present and future shareholders, for our customers, and most of all for Google users.”

—Founders’ IPO letter, Alphabet Inc.

The data bear this out. Among top tech companies (Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and Facebook), 96 percent of their total value has been created during their time as public companies. Since the 1970s, 92 percent of corporate job creation has occurred after companies IPO.

Finally, recent evidence suggests that public companies invest more than private ones. According to one study, following IPO firms increase their overall investments in long-term assets by 52 percent and continue to see increases for 10 years following public listing. Investments like this are where long-term value is unlocked.

Top five companies by market cap since IPO:

Going public is expensive: it entails an underwriting fee of 4-7 percent of gross proceeds and other fees often totaling over $4 million. Companies also bear a significant cost to stay public due to regulatory and reporting requirements.

For small companies, their reticence to take on these costs makes sense. Although these costs are real, they are dwarfed by the potential gains to public ownership for large, innovative companies.

Opportunities for employees and savers

In addition, going public is essential for providing competitive wealth creation opportunities for employees. Private markets do not offer the liquidity or scale to finance stock sales for a broad swath of employees at a competitive price. By contrast, Microsoft’s 1986 IPO and subsequent performance created three billionaires and an estimated 10,000 millionaires among Microsoft employees, as of 20004 As of 2007, Google’s IPO and growth had left more than 1,000 employees with stock grants and options worth more than $5 million. While founders have often been able to find the liquidity they need through private transactions for large blocks of shares, employees typically need the liquidity provided by public markets.

For companies in competitive markets, this matters. Nearly a third of senior business leaders cite competition for employee talent as their most significant challenge. With evidence that high performers are 400 percent more productive than average employees, that focus seems justified. As a means of attracting and retaining top talent, there is a strong case to be made for going public.

Furthermore, the benefits of public markets as a means of wealth creation are not isolated to insiders. According to the CFA Institute, the trend towards staying private has the unintended side effect of locking individual savers out of some of the economy’s fastest growing companies. In many countries, private investments are limited to “qualified” (wealthy) investors or institutional investors. Savers who invest on their own or through defined contribution (DC) retirement plans typically cannot access private investments. Going public allows individual savers to participate in the dynamism and growth of emerging companies, spreading the benefits of wealth creation.

Low-cost, stable capital

At their core, however, public markets are more than a way to compensate employees or spread the gains of economic growth. Fundamentally, they are a way of raising capital for growing enterprises. And they remain the best way of doing so for global companies operating at global scale. There’s a reason that, when push comes to shove, the world’s leading companies almost unanimously vote with their feet and go public.

To begin with, public markets remain unrivaled as providers of low-cost capital and high liquidity. The sheer size of public equities markets ($30 trillion in the US and $90 trillion globally) alone provides some indication of the amount of capital available by listing publicly. As one commentator put it, “private markets still cannot compete with the liquidity of public equity.” Moreover, the high level of information and disclosure required for participation in public markets has been shown to lower companies’ cost of capital, ceteris paribus.

These advantages should be even more salient for the largest, most scrutinized startups. As financial journalist and former investment banker Matt Levine has pointed out, it is already possible to “track Uber’s quarterly financial performance, and its stock-price fluctuations, and its activist shareholder campaigns.” The disclosure costs of going public have in many cases migrated to private markets as large, sophisticated investors demand transparency. If, for the companies in question, such disclosure costs are at near parity between public and private markets, the financial advantages of going public ought to be more tempting. And as of this writing, the SEC itself is considering ways to lessen the public company disclosure burden to facilitate long-term orientation.

For evidence that the balance may be swinging back toward public listings, look no further than the original titans of private markets: private equity firms. Although they cut their teeth as private markets investors, large private equity firms like Blackstone, KKR, and Carlyle have chosen to go public themselves. As the New York Times puts it, for Blackstone “going public conferred a certain brand status . . . [and] provided a currency to reward employees and expand the firm.” Moreover, “Opening its books to public scrutiny also may have made it easier for Blackstone to get a credit rating. That in turn has allowed it to borrow and to entice incoming fund investors with an extra demonstration of its financial robustness.” These advantages hold true for other companies that go public too.

The bottom line is that while staying private makes more sense than ever for small, rapidly-growing startups, public markets remain the destination-of-choice for large firms. Whether for wealth creation, employee retention, capital formation, or prestige, there is no denying the enduring appeal of public markets.

How the Successful Companies Thrive in Public Markets

All of this suggests that for the most economically significant companies, there remains an exceptionally strong case to enter the public equities market. Many of today’s leading companies have not only survived in public markets but thrived. For private companies on the cusp of an IPO, the secret to this success is far from a black box. The approaches of the most successful, long-term-oriented public firms point to clear, actionable strategies that companies can use to make public markets work for them.

1. Long-term companies define their shareholder strategy

Companies typically have well-defined customer strategies; successful long-term public companies do the same with shareholders. Advocates of private markets often point to their supportive, understanding investors as an advantage. But public markets investors needn’t be any less supportive. A comprehensive, well-executed shareholder strategy can ensure major public shareholders are similarly helpful.

Targeting long-term shareholders

Not all shareholders are created equal. By building a base of long-term shareholders, public companies can receive the support they need to facilitate long-term value creation rather than focusing on short-term targets. For example, individual savers, index funds, and institutional investors such as pension funds come to the table with long-term horizons that match the needs of growing companies. A long-term investor base reduces a company’s cost of equity, in part due to the superior monitoring these investors provide and the strong match between their goals and the companies in which they invest. The presence of long-term investors also reduces stock price volatility, encourages greater fixed investment, and is even associated with higher returns. By contrast, short-term investors can encourage volatility and management turnover as they push for near-term shortcuts at the expense of long-term strategy. At a minimum, leading companies understand the time horizon and incentives of the various market participants with which they interact. Once these horizons are understood, especially for shareholders, it becomes possible to develop a strategy to manage them by cultivating long-term supporters.

Replacing quarterly guidance with long-term roadmaps

In the US, the SEC has already begun to investigate the potential costs of quarterly guidance and its contribution to corporate short-termism. But companies need not wait for regulators to act. As FCLTGlobal has argued previously, moving past quarterly guidance and toward long-term plans promotes a long-term orientation among investors. By emphasizing the company’s long-term strategy through coordinated investor communications, successful companies focus investors on the information that matters for long-term value creation. Quarterly guidance does little to reduce volatility or improve valuation. And the best evidence suggests most investors do not even want it. Those that do are often the sort of investors that long-term companies want to avoid, transient owners attracted to opportunities to pressure managers to make decisions that boost the stock price today but sacrifice real, enduring value. Indeed, those most demanding of short-term guidance are often not shareholders at all but sell-side and media analysts who are heavily incentivized to focus on the short term. Long-term shareholders have shown comfort with, and often a preference for, long-term strategies and roadmaps.

Encouraging board-level engagement with shareholders

Private companies, especially startups, often tout the expertise and value they receive from their boards. When done right, a public company board is no different. Public companies benefit from working closely with their boards to educate them and deepen their understanding of long-term shareholders’ objectives. Doing so makes boards active participants in the process of cultivating long-term shareholders and ensuring shareholder and management objectives align. This sort of engagement is critical. Seventy-seven percent of S&P 500 companies report director engagement with shareholders over the past year; of that group, 45 percent reported making changes on the basis of that engagement.

Emphasizing cumulative reporting in investor discussions

One way to shift the dialogue is to focus on cumulative, year-to-date reporting—providing quarterly updates with the emphasis on progress toward annual goals, rather than a standalone comparison of each quarter to the prior quarter or the same quarter of the prior year. DSM, a global science-based company focused on the health and nutrition markets, takes a more novel approach and only reports cumulative results. The goal of cumulative reporting is to re-orient investor-corporate dialogue toward long-term goals and to mitigate the influence of quarterly results on corporate decision-making, such as giving discounts to close business in one quarter versus the next. Such reframing is largely costless—although traditional quarterly reports must be filed with regulators, managers hold substantial ability to set the tone of the dialogue with investors and internally in their presentation of financial results. And cumulative reporting need not be a standalone endeavor. Ideally, reframing quarterly dialogue in terms of cumulative results can catalyze other channels for long-term thinking as managers, directors, and shareholders recalibrate their frames of reference and expectations for performance.

2. Long-term companies build strong, focused boards

The board holds a crucial role in promoting long-term thinking. Having board directors engage with shareholders is valuable but on its own is not enough. The development of the board itself and definition of its role also offer meaningful opportunities to promote long-term orientation and public markets success.

Defining long-term goals and responsibilities The board of directors can best serve long-term shareholders when it has a focal point around which to center its efforts. A clearly defined statement of responsibilities for the board offers a starting point for the company’s long-term strategy. Directors know exactly what they are there to accomplish and how it fits into the company’s broader approach to value creation.

For example, Amazon’s statement of responsibility emphasizes “The Board of Directors is responsible for the control and direction of the Company. It represents and is accountable only to shareowners. The Board’s primary purpose is to build long-term shareowner value.” In a similar vein, HSBC’s board statement provides, in relevant part, that “The Board is collectively responsible for the long-term success of the Company and the delivery of sustainable value to shareholders.”

Effective board statements are unequivocal in establishing the board of directors’ duties and objectives. That sense of purpose, in turn, grounds the directors’ understanding of long-term strategy and how their engagements with shareholders fit into it.

Prioritizing diversity

By now, the finding that diverse boards outperform homogenous ones is well-known. Effective companies strive to assemble boards whose composition is reflective of the future of both the company and broader society. Diverse boards can improve decision-making by introducing a wider spectrum of knowledge and perspectives into the boardroom and by reducing the risk of groupthink that comes with homogeneity. Board-level diversity can also signal to other stakeholders, especially employees, that diversity matters to the company. To the extent this energizes and motivates employees, board diversity can be a driver of long-term performance. Research from Credit Suisse finds that companies with more than one woman on their board deliver excess returns of 3.7 percent annually. Another recent study found that firms with greater board diversity performed better and experienced lower volatility. This is low-hanging fruit—all companies can take advantage of the clear advantages of board diversity.

Continuous board development and education Boards, like managers and employees, can perform well or poorly. Studies show that investments in directors’ skills—to keep them current and relevant to the company’s needs—pay off. Leading companies adopt a continuous approach to board education: they solicit input from outside experts, keep the board abreast of peer-group best practices, provide research on industry and competitor dynamics, and keep board members informed about developments in their areas of responsibility. This effort pays off. Companies with more experienced boards perform better during downturns.

Similarly, companies with boards of directors who shift roles, receive performance evaluations, and require board members to continue building their knowledge over the course of their tenure tend to outperform.

And, of course, performance evaluations and continuing education for board members can also help the board reach its full potential. The most engaged directors report a high degree of familiarity with the company and its industry dynamics. Such knowledge requires investment by directors and, in turn, long-term investment by companies in building boards with members who will meet these high standards.

Understanding the board’s role as a strategic asset Collectively, the above findings point to a broader takeaway: that boards matter for long-term performance. Successful companies treat them as strategic assets, investing in them and continually ensuring they deliver. One way to put this mindset into action is to have board members participate regularly and intensely. Research from McKinsey & Company found that high-impact boards spend about 40 days per calendar year on their duties, compared to moderate or low-impact boards who spend just 19 on average. Those extra days tend to matter most when spent on strategy: high-impact boards spent three times as many days on strategy as lower-performing boards.

3. Long-term companies maintain an ownership mindset

The approaches listed above are tried and true. Two additional approaches borrowed from the world of family-owned companies can also help companies achieve long-term success in public markets.

CEO stock-based compensation lock-ups

Many successful public companies have an anchor shareholder, such as a founder or a family. One innovative option to recreate this dynamic for broadly held companies is to lock up a substantial share of CEO compensation in the form of stock redeemable only five or ten years out, and importantly, beyond the CEO’s expected tenure. As a recent paper from Norges Bank, one of the world’s largest long-term institutional investors, puts it: “The board should ensure that remuneration is driven by long-term value creation and aligns CEO and shareholder interests. A substantial proportion of total annual remuneration should be provided as shares that are locked in for at least five and preferably ten years, regardless of resignation or retirement.”

The logic for CEO shareholding lock-ups is simple: by deferring their compensation and linking it to long-term stock performance, CEOs are highly incentivized to focus on long-term value creation and succession planning. Just as in a family company, there is little principal-agent gap between the CEO and shareholders, and management cannot maximize their own compensation by juicing short-term returns at the expense of long-term value. Although largely untested by today’s publicly listed and broadly owned companies, the prima facie case for locking up CEO share-based compensation is strong. And while perhaps not strictly locked-up, most founder-led or closely-held companies have de facto lock-ups for their CEOs.

Aligning board incentives with long-term shareholders through long-term stock ownership

Finally, a similar approach can be used to align the incentives of board members with long-term value creation for shareholders, as is typical in a family-owned company. As with the CEO, in many regions board members can be compensated with stock or required to invest their cash compensation in stock to achieve mandated ownership thresholds. And the redemption of that stock can be deferred to focus their sights on the long-term. Many companies already compensate their directors in restricted stock units and others provide incentives for board members to purchase shares on their own. But the key to inspiring a board-level long-term ownership mentality is restricting sale of that stock for long periods of time. For companies considering going public, the approach of ensuring significant ongoing ownership by board members can be not only embraced but extended to deepen directors’ long-term alignment with public shareholders.

Conclusion

Public markets remain a critical element of global economic dynamism. Narrow focus on the declining number of IPOs and listed companies in developed markets misses the point. In these same markets, public market capitalization as a share of GDP is at an all-time high. And in developing markets, IPOs and public listings remain strong. The perceived decline of public markets mostly reflects small companies’ ability to stay private longer by relying on private capital.

For the largest, most economically significant companies, however, public markets are indispensable. Their unrivaled wealth creation capacity, ability to spread that wealth to employees and savers, and provision of low-cost, stable capital remain important advantages. For this reason, even unicorns like Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb—the stars of the venture capital world—are beginning to turn their eyes to public markets.

And they have every reason to, despite the short-term pressures that can accompany a public listing. By developing and executing a well-defined shareholder strategy, building a focused board with the right incentives and expertise, and maintaining an ownership mindset, the next generation of leading companies is well-positioned to thrive and deliver long-term value. The era of public markets is far from over.

Practical Tools to Mitigate the Short-Term Pressures of Public Markets

Public markets are an essential driver of wealth creation, innovation, and capital stability for high-performing companies. However, publicly listed companies often feel pressure to be short-term oriented. The best-managed companies both take advantage of the benefits public markets have to offer and maintain their long-term focus, often by employing the following tools We hope these tools will help leaders of public companies thrive in pursuit of long-term value creation.

Have a Well-Defined Shareholder Strategy Similar to a Well-Defined Customer Strategy

Target long-term shareholders and seek to increase their presence in the shareholder base

- Analyze shareholder base by size, investment strategy, and holding period to understand which shareholders emphasize long-term value creation

- Recognize that the “investment community” includes shareholders with different timeframes as well as non-shareholders such as the media or sell-side analysts

- Allocate senior management time toward long-term shareholders

- Reward investor relations professionals for focus on long-term shareholders, rather than for activity more broadly

Avoid quarterly guidance by implementing long-term plans

- Eliminate or do not begin to issue quarterly guidance

- As a first step, provide a long-term roadmap with a 3-5 year time horizon, including:

- Core drivers of growth and competitive advantages

- Long-term objectives

- Strategic plan

- Capital allocation priorities

- KPIs to track progress to plan

Encourage board-level engagement with shareholders and consider designating specific board members to engage with shareholders

Emphasize cumulative, year-to-date reporting in investor communications rather than comparisons of each quarter to the prior quarter or the same quarter of the prior year

Build a Strong Board Focused on Long-Term Value Creation

Adopt a clearly defined statement of the board’s long-term goals and responsibilities

- For example, Amazon’s statement of responsibility emphasizes “The Board of Directors is responsible for the control and direction of the Company. It represents and is accountable only to shareowners. The Board’s primary purpose is to build long-term shareowner value.”73

Make board diversity a priority

- Reflect the future of the organization rather than the past

- Pursue appropriate demographic mix (gender, age, geography)

- Recognize need for board members suited for both times of crisis and calm

Take a continuous approach to board director development and education

- Cultivate expertise in relevant disruptive technologies or business models related to long-term strategy

- Provide long-term training or development opportunities for board members

Treat the board as a strategic asset

- Dedicate staff for board members to leverage their time and expertise towards strategic work

- Focus the content of board materials on strategic issues and limit the length

- Allocate bulk of meeting time to discussing long-term business strategy, durable capital structure, talent development strategy and enterprise risk management

Ensure an Ongoing Ownership Mindset

Lock up CEO stock-based compensation for 5-10 years including beyond term of service

Align board incentives with long-term shareholders through long-term stock ownership

- Offer a company matching program for director stock purchases to inspire additional stock ownership

- Implement a minimum holding requirement for awarded or match purchased shares

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print