Grant Fondo and Michael Jones are partners and Nicholas Reider is an associate at Goodwin Procter LLP. This post is based on a Goodwin memorandum by Mr. Fondo, Mr. Jones, Mr. Reider, Hayes Hyde, Daniel Mello, and Janie Miller.

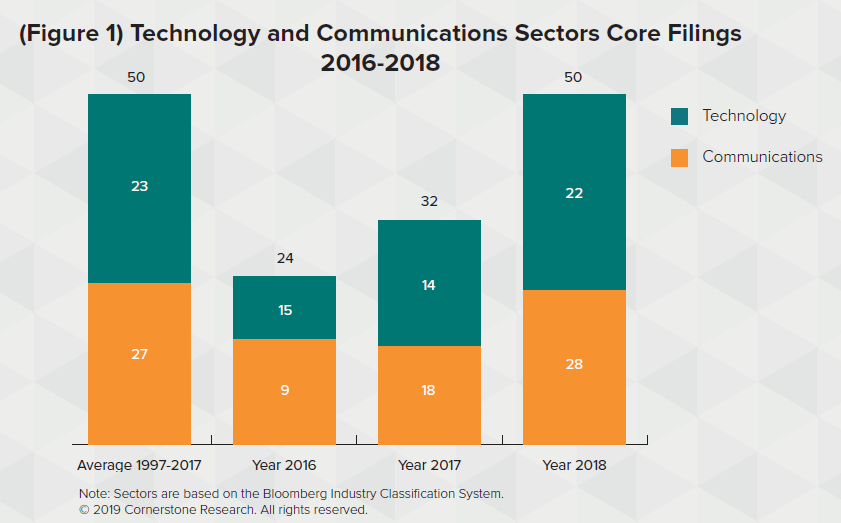

In 2018, Plaintiffs filed 403 new federal securities class actions, which was a 2% decrease from 2017 but still nearly double the average of annual filings from 1997-2017. [1] The 2018 filings included more than 180 cases challenging disclosures made in connection with mergers and acquisitions (M&A filings) and the fifth-highest number of “core” filings (excluding M&A filings) on record. [2] As depicted in Figure 1 below, the number of filings against publicly traded companies in the Technology and Communications sectors (collectively referred to herein as “technology companies”) increased by 56% from 32 in 2017 to 50 in 2018. [3] In 2018, the likelihood of an S&P 500 technology company being targeted with a new securities class action rose to the highest level since 2002 with approximately 13% of such technology companies subject to new cases—up from 8.5% in 2017 and the second highest percentage across all sectors. [4]

These cases are typically filed by shareholders seeking to recover investment losses after a company’s stock price drops following corporate disclosures. Plaintiffs typically assert claims under Sections 10(b), 20(a) and Rule 10b-5 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “1934 Act”) based upon allegedly false and misleading statements or omissions made by the company and its officers, and, if the alleged misstatements or omissions are made in connection with a securities offering, under Sections 11, 12(a)(2) and 15 of the Securities Act of 1933 (the “1933 Act”). In the merger context, plaintiffs typically assert claims under Sections 14(e) and 20(a) of the 1934 Act based upon allegedly false and misleading statements or omissions made by the selling and acquiring companies, and the selling companies’ officers and/or directors.

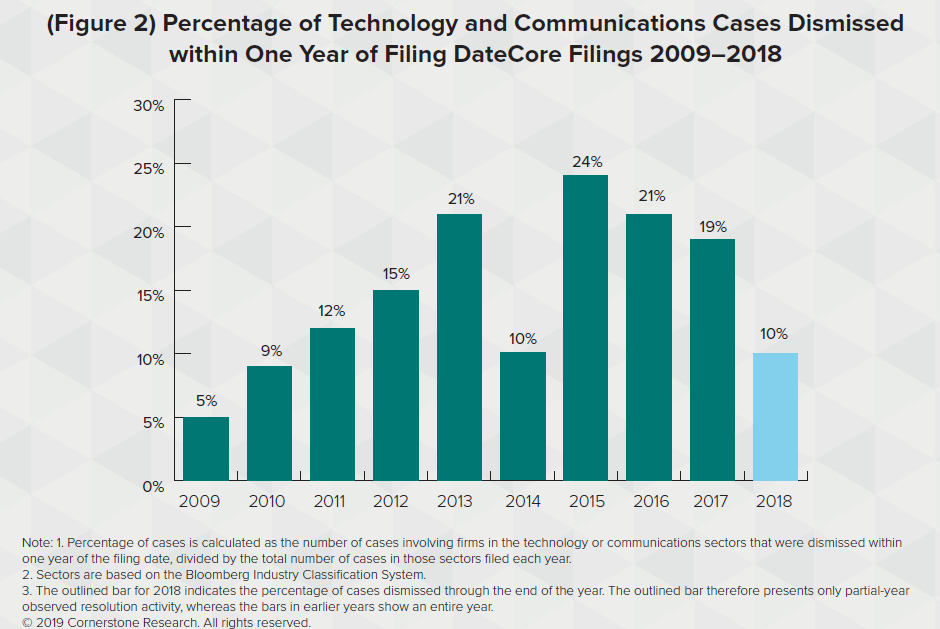

The plaintiffs’ bar, and a few select plaintiffs’ law firms in particular, [5] have focused on technology companies in recent years likely due to the number of companies in the sector and the potential volatility in stock prices. Last year, a record number of cases (approximately 24%) filed in 2017 had already been dismissed by year-end. Unfortunately, this trend has not continued for cases filed in 2018. As detailed in Figure 2, approximately 10% of securities class actions filed against technology companies in 2018 have been dismissed by year-end. However, given that the typical life cycle of securities class actions is approximately 18 months from the filing of the initial complaint through the disposition of defendants’ motion to dismiss, we expect that the percentage of dismissals will increase substantially by the end of 2019.

The Ninth Circuit was particularly active this year, with the highest number of securities class actions (against companies in all sectors) on record, increasing from 45 filings in 2017 to 69 filings in 2018. [6] This report focuses primarily on some of the more interesting decisions in the cases brought in the Ninth Circuit and the California Federal Courts. In addition, this report provides an update on new developments in the area of blockchain and digital currency.

The Ninth Circuit and California district courts issued several significant, detailed decisions dismissing virtually all claims against technology companies in various growth stages, as well as against their directors and officers. These cases involve disclosures concerning the types of issues that technology companies may face, including earnings results, future growth prospects and revenue projections, adjustments to guidance, financial restatements, internal control issues, mergers and acquisitions, or a setback or problem experienced by the company with respect operations. These courts dismissed most of these actions on the basis that plaintiffs failed adequately to allege that the defendants’ statements were false or misleading and/or that plaintiffs failed to allege particularized facts—as required under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 9(b) and the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (“PSLRA”)—that the defendants made false and misleading statements or omissions with scienter (i.e., intentionally or recklessly).

In particular, the Ninth Circuit issued two decisions in 2018 related directly to pleading standards in securities class actions. In one case, the Ninth Circuit examined two competing lines of case law in the Ninth Circuit regarding loss causation. The Ninth Circuit disagreed with the defendants’ position that plaintiffs must plead that the actual fraud was revealed and held that loss causation can be established if there was a causal connection between the facts misrepresented or concealed, and the alleged loss. In another key case, the Ninth Circuit reversed the district court’s dismissal of Section 14(e) claims challenging merger disclosures and held that Section 14(e) does not require intentional wrongdoing (scienter), but rather, requires only negligence. In doing so, the Ninth Circuit split from the Second, Third, Fifth, Sixth, and Eleventh Circuit decisions on which the district court relied. The Supreme Court granted Defendants’ petition for review and will be hearing that case in 2019.

As noted above, this report also provides a brief overview of significant developments in the blockchain and digital currency space, with technology companies conducting approximately 1500 token sales (commonly referred to as “initial coin offerings” or “ICOs”), raising more than an estimated $26 billion in total. Building off of guidance published in 2017, the federal government has remained active in monitoring token sales to determine whether they involve potential violations of the federal securities laws, and civil plaintiffs also have alleged such violations. In 2018, class action filings related to ICOs or cryptocurrency nearly doubled from 5 in 2017 to 9 in 2018. In these matters and other enforcement actions, the courts have taken on the issue of whether federal laws govern ICOs and, if so, which.

Ninth Circuit Cases*

Mineworkers Pension Scheme v. First Solar, Inc.,

881 F.3d 750 (9th Cir. 2018)—Loss Causation Standard

First Solar, Inc. (“First Solar”) is one of the world’s largest producers of photovoltaic solar panel modules. In July 2010, First Solar disclosed an “excursion,” or deviation, that had occurred in its manufacturing process and that potentially resulted in early power loss for affected solar modules comprising 4% of the total products First Solar manufactured within the relevant time period. At the time, First Solar reported that it had accrued approximately $30 million in expenses to replace affected modules. Thereafter, in February 2012, First Solar announced lower-than-expected revenue and earnings for the fourth quarter of 2011, reduced 2012 revenue guidance below analyst estimates, and pre-tax charges of $393 million related to goodwill impairment and $60 million related to restructuring activities. First Solar’s stock declined 11% the following day.

Investors filed a securities class action lawsuit against First Solar and its officers, alleging that defendants wrongfully concealed certain defects associated with the company’s solar panels, misrepresented the cost and scope of the defects, and reported false information in their financial statements, in violation of Sections 10(b) and 20(a), and Rule 10b-5 of the 1934 Act. After the district court denied defendants’ first motion to dismiss, and subsequent proceedings, First Solar filed a motion for summary judgment on all claims. The U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona granted in part and denied in part that motion, holding that plaintiffs had advanced triable issues of material fact on several claims. The district court stayed the action, however, because it perceived two competing lines of case law in the Ninth Circuit regarding loss causation. Under the first and more restrictive line of case law—which would have supported summary judgment in favor of defendants—loss causation could be proven only if the market learned of defendants’ fraud, and could not be proven if investors merely were injured by the consequences of the fraudulent practices as opposed to an actual revelation of fraud. Under the second line of case law—the more general proximate cause test – loss causation could be established if there was a causal connection between the facts misrepresented or concealed, and the alleged loss. The district court adopted the second line of case law, but certified for an interlocutory appeal the question of which loss causation test applies in the Ninth Circuit.

The Ninth Circuit affirmed the lower court’s conclusion that the correct test for loss causation under the 1934 Act is the general proximate cause test, relying on its prior decision in Lloyd v. CVB Financial Corporation, 811 F.3d 1200 (9th Cir. 2016). Specifically, the Ninth Circuit concluded: “That a stock price drop comes immediately after the revelation of fraud can help to rule out alternative causes. But that sequence is not a condition of loss causation.” Rather, to establish loss causation under the 1934 Act, a plaintiff need only establish that the “defendant’s misstatement, as opposed to some other fact, foreseeably caused the plaintiff’s loss.”

A petition for review of the Ninth Circuit’s decision currently is pending before the Supreme Court.

*The allegations and facts set forth in the case summaries herein are taken from the courts’ decisions or, for cases to watch, from the pleadings, and we are not commenting on the truth or accuracy of the allegations and facts.

Varjabedian v. Emulex Corporation, et al., 888 F.3d 399 (9th Cir. 2018)—Negligence vs. Scienter Standard in Tender Offer Context

Emulex Corporation (“Emulex”) was a technology company that sold storage adaptors, network interface cards, and other products. In February 2015, Emulex and Avago Technologies Wireless Manufacturing, Inc. (“Avago”) announced that they had entered into a merger agreement, pursuant to which Avago would offer to pay $8.00 for all outstanding shares of Emulex stock, representing a 26.4% premium over Emulex’s stock price the day before the merger was announced. Pursuant to the merger agreement, an Avago merger subsidiary initiated a tender offer for Emulex’s outstanding shares in April 2015. In connection with that tender offer, Emulex filed a Schedule 14D-9 Recommendation Statement with the SEC, which supported the tender offer and recommended that Emulex’s shareholders tender their shares.

Emulex investors filed a securities class action, asserting claims under Sections 14(d)(4), 14(e), and 20(a) of the 1934 Act, alleging that Emulex, its board of directors, Avago, and the merger subsidiary misled investors by failing to summarize an analysis conducted by Emulex’s financial advisor, which would have disclosed that the 26.4% premium was below average compared to similar mergers. The district court dismissed the complaint with prejudice, holding that Section 14(e) requires a showing of scienter and that plaintiffs had not adequately alleged scienter. The district court also concluded that Section 14(d) does not establish a private right of action for shareholders, and that plaintiffs’ Section 20(a) claims necessarily failed because plaintiffs had not adequately pled their claims under Sections 14(d) or 14(e). The district court also concluded that the merger subsidiary was not a proper party to the lawsuit because it ceased to exist when the transaction closed.

Although the Ninth Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision that Section 14(d) does not establish a private right of action, and that the Avago merger subsidiary was not a proper party, the Ninth Circuit reversed the district court’s dismissal of the plaintiffs’ claims under Sections 14(e) and 20(a). Specifically, diverging from the Second, Third, Fifth, Sixth, and Eleventh Circuit decisions on which the district court relied, the Ninth Circuit concluded that Section 14(e) does not require scienter, but rather, requires only negligence.

The Ninth Circuit explained that other courts erroneously had concluded that Section 14(e) of the 1934 Act requires scienter because Rule 10b-5 requires scienter. According to the Ninth Circuit, “Rule 10b-5 requires a showing of scienter because it is a regulation promulgated under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act, which allows the SEC to regulate only ‘manipulative or deceptive devices,’” and “[t]his rationale regarding Rule 10b-5 does not apply to Section 14(e), which is a statute, not an SEC Rule.” The Ninth Circuit reasoned that the plain language of Section 14(e) is “nearly identical” to that of Section 17(a)(2) of the 1933 Act, which “does not require a showing of scienter” under well-established Supreme Court precedent. Moreover, the Ninth Circuit reasoned, the legislative history of Section 14(e) places greater emphasis on the quality of information disclosed in connection with tender offers than on the state of mind harbored by those conducting a tender offer. The Ninth Circuit thus reversed the district court’s dismissal of plaintiffs’ Section 14(e) claims – and of plaintiffs’ Section 20(a) claims predicated on Section 14(e) violations – and remanded for further proceedings. Defendants appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and on January 4, 2019, the Supreme Court granted Defendants’ petition for review. Argument is scheduled for April 15, 2019.

Webb v. SolarCity Corporation, et al., 884 F.3d 844 (9th Cir. 2018) – Accounting Error and Understated Costs

SolarCity Corporation (“SolarCity”) was a company that sold renewable energy through the leasing and outright sale of solar energy systems. The revenues generated by SolarCity’s sales and leases were accounted for differently in SolarCity’s financial records. Sales revenues were recognized when units were installed and passed inspection, and associated sales costs, including direct costs of each sale and indirect overhead costs, were realized at the time of sale. Lease revenues, by contrast, were accounted for ratably—and installation and overhead costs were amortized—over the term of each lease. SolarCity conducted an initial public offering in December 2012. Beginning in the first quarter of 2012 and continuing for seven consecutive quarters, SolarCity failed to adhere to its GAAP-compliant protocols by pushing its sales division’s direct costs onto its leasing division, where such costs would be amortized over time. In March 2014, SolarCity announced this accounting error, and issued restated financials for the years and each quarter of 2012 and 2013. These disclosures revealed that SolarCity’s sales unit had operated at a loss for six quarters, and barely broke even in two quarters. Thereafter, SolarCity’s stock price fell by nearly 30% to $23.58.

Investors filed a securities class action against SolarCity and its officers, asserting claims under Sections 10(b) and 20(a), and Rule 10b-5 of the 1934 Act. The district court granted defendants’ motion to dismiss for failure to adequately allege scienter. The Ninth Circuit affirmed the district court’s dismissal on the same basis.

Viewing the allegations of the complaint holistically, the court concluded that “[a]t best,” the allegations, which were based on accounts of 11 confidential witnesses, “paint a picture of a mismanaged organization in need of closer financial oversight that made a minute error at a critical stage in its development.” The court credited the confidential witnesses’ accounts, which demonstrated that SolarCity’s officers knew that SolarCity was generally unprofitable, were hands-on managers, and had reason to suspect that the company’s internal accounting controls were imperfect. Nonetheless, the court emphasized that the officers did not sell SolarCity stock during the class period, which “detract[ed] from a scienter finding.” Moreover, defendants were forthcoming in that they stated in the company’s IPO prospectus that SolarCity was not profitable, and the 2014 restatement merely increased the company’s stated losses. The court also concluded that plaintiffs did not adequately allege scienter based on defendants’ alleged motive to “boost” the company’s profitability and stock prices surrounding its 2012 IPO, reasoning that the same is true of “every company that goes public.” Nor did the alleged departures of senior company officers close in time with the 2014 restatement establish a compelling inference of scienter, as plaintiffs alleged no facts rebutting the “reasonable presumption” that these departures “occurred as a result of the restatement’s issuance itself.” Finally, the court declined to infer scienter based on the accounting issues’ alleged importance to SolarCity, reasoning that plaintiffs’ generalized allegations about defendants’ access to reports that may have documented these issues were insufficient, that the sales division in which the accounting issues occurred “accounted for less than 10%” of SolarCity’s annual installations, and that the error “was so subtle that it appears that even the company’s specialized accounting division and professional auditors missed it” for seven consecutive quarters.

Stoyas v. Toshiba Corporation, et al., 896 F.3d 933 (9th Cir. 2018) – Applicability of U.S. Securities Laws to American Depository Shares

Toshiba Corporation (“Toshiba”) is a Japanese technology company offering products and services including computer systems, consumer electronics, and other information technology equipment and systems. On September 7, 2015, Toshiba restated its pre-tax profits for fiscal years 2008 through 2014, admitting substantial institutional accounting fraud. This restatement eliminated $2.6 billion in profits, or approximately one-third of Toshiba’s total reported profits during the relevant period, as well as $9.9 billion in equity. As a result, Toshiba’s stock price declined by more than 40%, constituting a loss of $7.6 billion in market capitalization.

On June 4, 2015, holders of Toshiba American Depository Shares (“ADRs”) filed a class action lawsuit under Sections 10(b) and 20(a), and Rule 10b-5, against Toshiba and its current and former CEOs. ADRs are financial instruments that enable investors in the United States to buy and sell stock in foreign corporations such as Toshiba. The SEC has stated that ADRs “allow U.S. investors to invest in non-U.S. companies and give non-U.S. companies easier access to U.S. capital markets.” The district court dismissed the complaint with prejudice, on the basis that under Morrison v. National Australia Bank Ltd., 561 U.S. 247 (2010), the 1934 Act does not apply extraterritorially, and thus does not apply to the purchase of Toshiba ADRs because the over-the-counter market on which the ADRs were sold was not a “national exchange,” and there was no domestic transaction between ADR purchasers and Toshiba. Plaintiffs appealed.

The Ninth Circuit first held that Toshiba ADRs “fit comfortably within the Exchange Act’s definition of ‘security,’” as ADRs are registered with the SEC and possess characteristics typically associated with common stock: “(i) the right to receive dividends contingent upon an apportionment of profits; (ii) negotiability; (iii) the ability to be pledged or hypothecated; (iv) the conferring of voting rights in proportion to the number of shares owned; and (v) the capacity to appreciate in value.” Moreover, the Ninth Circuit reasoned, the “economic reality” of ADRs is “closely akin to stock” because: ADRs are denominated in U.S. dollars, cleared through U.S. settlement systems, and listed alongside U.S. stocks; prospective ADR investors have access to English translations of informational material provided to Toshiba’s common stockholders; and ADR owners can obtain legal ownership of Toshiba common stock in exchange for their ADRs at any time.

The Ninth Circuit declined to decide whether the 1934 Act applied to the ADR transactions at issue because the over-the-counter market on which the ADRs were sold was a “national exchange.”

Expressly adopting the Second and Third Circuits’ so-called “irrevocable liability” test for determining whether securities purchases and sales are “domestic transactions” subject to the 1934 Act, the Ninth Circuit held that the ADR transactions at issue potentially were covered “domestic transactions” because the investors, over-the-counter desk, and several Toshiba ADR depositary institutions were based in the U.S., and thus the purchasers and sellers potentially incurred irrevocable liability to one another in the U.S. upon the completion of the ADR trades. The Ninth Circuit concluded that the district court erroneously denied plaintiffs leave to amend their complaint to add allegations establishing that the ADR transactions were “domestic transactions.” The Ninth Circuit reversed and remanded the decision for further proceedings in the district court, holding that while plaintiffs had failed to adequately allege the existence of a domestic securities transaction, leave to amend would not be futile. Thereafter, Toshiba filed a petition for a writ of certiorari with the U.S. Supreme Court, and a decision on that petition has not yet been issued.

California District Court Cases

In re Extreme Networks, Inc. Securities Litigation, Case No. 15-cv-04883-BLF, 2018 WL 1411129 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 21, 2018) – Expected Synergies Following Acquisition, and Revenue Growth from Partnership

Extreme Networks, Inc. (“Extreme”) develops and sells network infrastructure equipment. Between September and October 2013, Extreme announced and closed its acquisition of a competitor, Enterasys Networks, Inc. (“Enterasys”). At the time of the acquisition, Extreme stated that it “planned” to reduce costs and expenses by $30 million to $40 million after fully integrating Enterasys, that these synergies were expected to be realized over 12 to 24 months, and that “[t]here would be no disruption in customers’ ability to grow and operate their networks.” In November 2013 and through 2014, Extreme stated that its integration efforts were on track or ahead of plan and that its integration of Enterasys’s sales force was complete, and reaffirmed its target for savings of up to $30 million to $40 million per year. In January 2015, however, Extreme disclosed that it had “considerable work to do going forward” to complete the integration.

At the same time, Extreme emphasized its partnership with Lenovo Group LTD. (“Lenovo”). In August 2014, Extreme stated that the Lenovo partnership would “generate significant revenues” for Extreme beginning in the fourth quarter of 2015 and beyond. In October 2014, Extreme’s CEO said that he expected double-digit revenue growth by June 2015 as a result of Extreme’s partnership with Lenovo. Throughout 2014, Extreme’s officers reaffirmed their “commitment” to achieve 10% revenue growth and operating margins by June 2015.

In January 2015, however, Extreme announced that it would not achieve double-digit revenue growth by June 2015, but nonetheless explained that its partnership with Lenovo had strengthened. On April 9, 2015, Extreme preannounced that it would miss its earnings estimates, and its stock price fell by approximately 25% from $3.24 to $2.50 per share. In May 2015, Extreme’s new CEO stated that Extreme had “zero visibility into Lenovo.”

Investors filed a securities class action against Extreme and its officers, asserting claims under Sections 10(b) and 20(a), and Rule 10b-5 of the 1934 Act. In a consolidated amended complaint, plaintiffs relied on six confidential witnesses in alleging that defendants made misrepresentations concerning the success of Extreme’s post-acquisition integration with Enterasys and Extreme’s partnership with Lenovo. Defendants moved to dismiss the consolidated amended complaint, which the court granted in part and denied in part. As to defendants’ initial statements concerning their plan to integrate Enterasys, their expectation that there would be no disruption to customers, and progress toward achieving savings, the court held that plaintiffs alleged no facts establishing that such statements were false. With respect to defendants’ positive statements concerning the status of Extreme’s integration of Enterasys, however, the court held that plaintiffs adequately pleaded falsity and scienter, in light of allegations based on confidential witness accounts that defendants were intimately involved in day-to-day operations surrounding the integration and that employees had voiced concerns to defendants concerning the inadequacy of Extreme’s integration. Moreover, the court held that plaintiffs’ allegations based on confidential witnesses supported a strong inference of scienter that defendants were apprised of the integration issues.

With respect to plaintiffs’ allegations concerning Lenovo, the court agreed with defendants that Extreme’s optimistic forward-looking statements about the partnership were inactionable opinions, and that Extreme’s new CEO’s later-in-time statements concerning Lenovo “cannot be deemed an admission” of what defendants “knew at the time the statements were made.” The court also concluded that defendants’ statements concerning their “commitment” to achieve double-digit growth were nonactionable because the word “commitment” is not an actionable “word of certainty,” but rather “inactionable puffery.”

Ziolkowski v. Netflix, Inc., et al., Case No. 17-cv-01070-HSG, 2018 WL4587515 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 25, 2018) – Price Increase’s Negative Impact on Growth

Netflix, Inc. (“Netflix”) is a subscription-based service company offering the online streaming of movies and television programs to its members. Following a price increase of its monthly subscription rate in 2014, an investor filed a class action against Netflix and its CEO and CFO under Sections 10(b) and 20(a), and Rule 10b-5, alleging that defendants made materially false and misleading statements related to Netflix’s operating results for the second quarter of 2014. The plaintiff identified statements from a shareholder letter in which the company stated that (1) its “net additions in the U.S. remain[ed] on par with last year,” and (2) “[t]here was minimal impact on membership growth from this price change.” During an earnings call on the same day, the company stated that the price change’s impact would be “pretty nominal,” “background noise,” and would have made “no noticeable effect in the business.”

The plaintiff also alleged that the 2014 second quarter report failed to identify the price increase as a “risk factor.” Plaintiff contended that the company effectively admitted falsity of its statements when it explained in the third quarter of 2014 that the price increase had a substantial negative impact on growth, but that the impact had gone unnoticed because it had been temporarily mitigated by the release of a new season for a popular show. According to the plaintiff, Netflix’s stock price declined by approximately 20% following this disclosure. Defendants moved to dismiss.

The district court granted defendants’ motion to dismiss, holding that the plaintiff had failed to meet the PSLRA’s exacting pleading requirements. First, the court held that the plaintiff failed to adequately allege that “defendant’s statements [ ] directly contradict what the defendant knew at that time,” as required under the Ninth Circuit’s recent decision in Khoja v. Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc., 899 F.3d 988, 1008 (9th Cir. 2018). The court explained that plaintiff’s allegations did not establish that the company’s net additions in the U.S. were actually “not on par with the previous year,” nor did plaintiff allege facts supporting his claim that the company did not believe the impact of the price was minimal. That the company later admitted that the price change had a negative impact on growth “amounted to only hindsight analysis.” As to scienter, the court found that the company’s subsequent third quarter statements were based on newly discovered information, and did not establish that defendants’ prior statements were misrepresentations at all. The court held that although “falsity and scienter are distinct inquiries, Plaintiff’s ability to plead facts showing Defendants acted with the requisite scienter is substantially hindered by his inability to plead the existence of a materially false or misleading statement or omission.”

Wanca v. Super Micro Computer, Inc., et al. Case No. 5:15-cv-04049-EJD, 2018 WL 3145649 (N.D. Cal. June 27, 2018) SOX Certifications and Subsequently Reported Material Weakness

Super Micro Computer, Inc. (“Super Micro”) provides high-performance server solutions to data centers, cloud computing, enterprise IT, big data, and related industries. Super Micro’s annual and quarterly reports in 2014 and 2015 included Super Micro’s officers’ signed certifications pursuant to the Sarbanes Oxley Act of 2002 (“SOX”). Through the SOX certifications, the company’s certifying officers represented that the financial information included in the reports fairly represented all material information, including disclosure of all significant deficiencies and material weaknesses in internal controls, and any fraud involving management or other employees who had a role in the company’s financial reporting. On November 16, 2015, Super Micro filed a Form 8-K/A acknowledging that a material weakness existed in the Company’s internal controls over financial reporting related to the revenue recognition of contracts with extended product warranties.

An investor filed a class action alleging claims under Sections 10(b) and 20(a) of the 1934 Act and Rule 10b-5 against Super Micro and its officers. Plaintiff alleged that the disclosure of the material weakness in November 2015 rendered all of the prior SOX certifications false and misleading. Defendants moved to dismiss, and the district court granted that motion. Specifically, the court reasoned that plaintiff failed to allege facts explaining why the SOX certifications were false at the time they were made, and that plaintiff could not satisfy his pleading burden under the PSLRA simply by “pointing out a later-discovered inaccuracy in certified reports,” particularly given that “SOX Certifications were not intended to create a per se violation of securities laws.” Nor did plaintiff allege any facts establishing that defendants issued their SOX certifications with actual knowledge of their falsity, had any motive to deceive the public, or sold any stock before the disclosure of the material weakness. Moreover, the court held that to the extent plaintiff challenged alleged misstatements or omissions made after he purchased shares, such statements were not actionable as a matter of law because such statements could not “have influenced his decision to purchase Super Micro stock, or in any way affected the price he paid” before such statements were made.

Wochos v. Tesla, Inc., et al., Case No. 3:17-cv-05828, 2018 WL 4076437 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 27,2018) – Missed Production Targets

Tesla, Inc. (“Tesla”) designs, develops, manufactures, and sells high-performance electric vehicles and solar energy generation and energy storage products. In 2016, Tesla announced plans to produce an affordable, mass-market electric vehicle, the “Model 3.” Tesla stated that it planned to develop a fully-automated production line, which would have made it the first mass-manufacturer of an all-electric vehicle. Tesla reported in May 2016 that it expected to achieve volume production and deliveries in late 2017. At that time, however, Tesla cautioned that it had experienced “significant delays or other complications” associated with other vehicles and “may experience similar delays or other complications in bringing to market and ramping production of new vehicles, such as Model 3.” Tesla also warned that it had “no experience” in manufacturing at the high volumes that it anticipated for the Model 3, and that its plans were built on many assumptions, including suppliers’ abilities to meet Tesla’s needs. Tesla’s CEO described in February 2017 “new issues that pop up every week,” and that the “things that are likely to be schedule issues are things that we actually just don’t know about today.” At a Model 3 unveiling event in July 2017, Tesla’s CEO stated that Tesla was entering “production hell,” and stated the following month that the company faced “an incredibly difficult production ramp.” In October 2017, Tesla issued a press release stating that Tesla had failed to meet its production goals because of “production bottlenecks.” Four days later, the Wall Street Journal reported that the few Model 3s that were being built were being constructed by hand rather than on an automated production line. During an October 2017 earnings call, Tesla’s CEO stated that “it’s looking good for production volume second half of 2017,” but cautioned that “a car consists of several thousand unique items,” and that Tesla could “only go as fast as the slowest item.” Tesla’s CEO cautioned that “it’s very difficult to predict exactly where the beginning part of the exponential curve . . . fits in between quarterly reporting.” Tesla’s quarterly report filed a few days later warned about the possibility that Tesla might not hit its Model 3 production targets. Thereafter, in November 2017, Tesla announced that it was pushing back its production goal of 5,000 vehicles per week to the first quarter of 2018. Tesla’s stock price declined by 6.8%.

Investors filed a securities class action lawsuit, alleging that Tesla and its officers violated Section 10(b) and 20(a), and Rule 10b-5, by misrepresenting Tesla’s progress with respect to bringing the Model 3 to market. Defendants moved to dismiss. The district court granted that motion, holding that defendants’ statements were forward-looking and thus protected under the PSLRA’s safe harbor.

The court rejected plaintiffs’ argument that Tesla’s predictions about achieving future goals were not forward-looking because they characterized the current state of affairs, reasoning that “every future projection depends on the current state of affairs,” and “were the Court to adopt Plaintiffs’ conclusion, the distinction between present statements and forward-looking statements would collapse.” The court also found that Tesla’s forward-looking disclosures meaningfully described “a host of uncertainties regarding the production process,” cautioned investors that it had “no experience to date in manufacturing vehicles at the high volumes” projected, and noted a number of assumptions underlying its production plan.

Plaintiffs filed an amended complaint in March 2018, alleging that defendants violated the Sections 10(b) and 20(a), and Rule 10b-5, by misrepresenting or failing to disclose that Tesla “had severely inadequate inventory and was woefully unprepared to launch the Model 3 sedan as anticipated” in late 2017. Defendants moved to dismiss the amended complaint in November 2018, and the motion is scheduled to be heard in March 2019.

Rodriguez v. Gigamon, Inc., 325 F. Supp. 3d 1041 (N.D. Cal. July 11, 2018) – Missed Earnings

Gigamon, Inc., is a technology company that offers network visibility and traffic monitoring software and related services. During a conference call on October 27, 2016, Gigamon’s CEO and CFO discussed Gigamon’s third quarter 2016 financial results. During the call, the CEO and CFO projected that Gigamon would earn revenues in the fourth quarter of between $91 million and $93 million, and that the company had a “large deferred service” and “healthy backlog” leaving it “on track to deliver our second consecutive year of accelerating top-line revenue growth and expanding profitability.” On November 2, 2016, Gigamon’s CEO stated in an interview that Gigamon was expecting fourth quarter revenues of only $89 million. Thereafter, on January 17, 2017, the company issued an earnings release which reported preliminary fourth quarter 2016 revenues of between $84.5 million and $85 million. Gigamon attributed this earnings miss to “lower than expected product bookings in our North America West region, as several significant existing customer accounts deferred purchasing decisions into 2017.” During an investor call in February 2017, Gigamon’s CEO repeated this explanation, and Gigamon’s CFO explained that its product backlog at quarter end was $3.1 million lower than it had been during the preceding six quarters. Gigamon’s stock price fell by 5.3%, from $32.10 per share to $30.40 per share.

Investors filed a securities class action complaint against Gigamon and its CEO and CFO, alleging claims under Sections 10(b) and 20(a) and Rule 10b-5. Plaintiffs alleged that defendants made materially false and misleading statements concerning anticipated revenues and Gigamon’s sales backlog. Defendants moved to dismiss on the grounds that plaintiffs had failed to identify actionable statements or adequately allege scienter. First, defendants argued that statements concerning the company’s “large deferred service” and “healthy backlog” were merely non-actionable predicate assumptions underlying its forward-looking revenue projections. The court disagreed, holding that those statements described “the present state of the Company” and were “not assumptions.” Nor did defendants couch statements concerning “backlogs” with any meaningful cautionary disclosures specifically related to “orders existing at the time” of the alleged misstatements, as opposed to generic cautionary language concerning future orders. And defendants’ statements about the company being “on track,” with a “healthy backlog” and “large” deferred services, were not mere “puffery.” Nonetheless, the court held that plaintiffs alleged no facts establishing that defendants’ optimistic statements were false when made. The court also held that plaintiffs failed to adequately allege scienter based on defendants’ stock sales during the class period, explaining that the CEO’s sales were made pursuant to a Rule 10b5-1 trading plan adopted more than one year before the alleged fraud, and that plaintiffs had failed to identify when the CFO made any particular stock sale.

Blockchain, Token Sales, and SEC Guidance

Over the past two years, there has been a significant amount of activity in the blockchain and digital currency space, with technology companies conducting approximately 1500 token sales (commonly referred to as “initial coin offerings” or “ICOs”), raising more than an estimated $26 billion in total. Building off of guidance published in 2017, the federal government has remained active in monitoring token sales to determine whether they involve potential violations of the federal securities laws, and civil plaintiffs also have alleged such violations. A brief overview of significant developments in this space follows.

Report of Investigation Pursuant to Section 21(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934: The DAO, Exchange Act Release No. 81207 (July 25, 2017)

The DAO, one example of a Decentralized Autonomous Organization, was a virtual organization embodied in computer code and executed on a distributed ledger, or blockchain, across computers worldwide. The DAO was an entity created to operate for profit by receiving and holding assets through the sale of DAO tokens to investors, and to use those assets to fund projects. Between April and May 2016, The DAO sold approximately 1.15 billion tokens, raising the equivalent of approximately $150 million. DAO token holders stood to share in the anticipated earnings from projects that The DAO funded as a return on their investment. DAO token holders could monetize their investments by re-selling those tokens on a number of exchanges. After DAO tokens were sold, but before The DAO began funding projects, an attacker used a flaw in The DAO’s code to steal approximately one-third of The DAO’s assets. The DAO’s creators and others responded by developing a work-around whereby DAO token holders could opt to have their investment returned to them. The SEC issued a Report of Investigation concerning The DAO (“The DAO Report”) to advise those who would use tokens to raise capital to take appropriate steps to ensure compliance with the federal securities laws.

In The DAO Report, the SEC explained that the DAO tokens were securities under the federal securities laws because they satisfied all of the elements of the test articulated by the U.S. Supreme Court in SEC v. W.J. Howey Co., 328 U.S. 293 (1946). The so-called “Howey test” includes four elements: (1) investment of money (the investor must provide assets); (2) common enterprise (the investor’s fortunes must be interwoven with those of other investors (i.e., “horizontal commonality”) and/or the efforts of the promoter of the investment (i.e., “vertical commonality”)); (3) reasonable expectation of profits (the investor must make the investment with the reasonable expectation that the value of the investment will increase or that the investor will otherwise earn profits from the investment (e.g., dividends or other periodic payments)); and (4) the profits are to be derived from the entrepreneurial and/or managerial efforts of others (the investor’s profits must be derived from the significant entrepreneurial and/or managerial efforts of the promoter of the investment or other third parties). The SEC concluded that DAO tokens satisfied all four elements of the Howey test and, therefore, were securities under the federal securities laws. In so concluding, the SEC “reiterate[d] these fundamental principles of the U.S. federal securities laws and describe[d] their applicability to a new paradigm—virtual organizations or capital raising entities that use distributed ledger or blockchain technology to facilitate capital raising and/or investment and the related offer and sale of securities.” The SEC further warned: “The automation of certain functions through this technology, ‘smart contracts,’ or computer code, does not remove conduct from the purview of the U.S. federal securities laws.” To the extent that U.S. federal securities laws apply to these new technologies, the SEC “stress[ed]” that individuals and entities raising capital through such technologies remain “obligat[ed] to comply with the registration provisions of the federal securities laws.”

Remarks by SEC Chairman Jay Clayton(November 8, 2017)

Following the release of the DAO Report, on November 8, 2017, SEC Chairman Jay Clayton provided additional guidance concerning the applicability of federal securities laws to token sales conducted through distributed ledger technologies. Specifically, Chairman Clayton reiterated: “The Commission recently warned that instruments, such as ‘tokens,’ offered and sold in ICOs may be securities, and those who offer and sell securities in the United States must comply with the federal securities laws.” Chairman Clayton further warned that federal securities laws likely apply to token sales: “I have yet to see an ICO that doesn’t have a sufficient number of hallmarks of a security.”

Munchee Inc., Securities Act Release No. 10445 (Dec. 11, 2017)

Munchee, Inc. (“Munchee”) was a California business that created an application for people to review restaurant meals. In October and November 2017, Munchee offered and sold tokens to raise capital to improve its application, and to recruit users eventually to buy advertisements, write reviews, sell food, and conduct other transactions using the tokens. In connection with the token offering, Munchee described the way in which the tokens would increase in value as a result of Munchee’s efforts, and stated that the tokens would be traded on secondary markets. On the second day of the token sale, Munchee was contacted by the SEC. Munchee stopped selling tokens within hours, did not deliver any tokens to purchasers, and returned to purchasers the proceeds that it had received.

The SEC concluded that the Munchee tokens satisfied all four elements of the Howey test and, therefore, were securities under the federal securities laws: “Among other characteristics of an ‘investment contract,’ a purchaser of [Munchee] tokens would have had a reasonable expectation of obtaining a future profit based upon Munchee’s efforts, including Munchee revising its app and creating the [Munchee] ‘ecosystem’ using the proceeds from the sale of [Munchee] tokens.” The SEC further concluded that “Munchee violated Sections 5(a) and 5(c) of the Securities Act by offering and selling these securities without having a registration statement filed or in effect with the Commission or qualifying for exemption from registration with the Commission.” The SEC ordered Munchee to cease and desist from committing or causing any violations of Section 5(a) and 5(c) of the 1933 Act. The SEC explained that in deciding not to impose a civil penalty, the SEC considered Munchee’s cooperation and remedial efforts.

Remarks by SEC Director William Hinman at the Yahoo Finance All Markets Summit: Crypto, “Digital Asset Transactions: When Howey Met Gary (Plastic)” (June 14, 2018)

During the June 14, 2018 Yahoo Finance All Markets Summit, William Hinman, Director of the SEC’s Division of Corporate Finance, explained that a token potentially can transform from a security to a non-security, depending on how decentralized the network on which the token is used becomes. Director Hinman stated: “If the network on which the token or coin is to function is sufficiently decentralized—where purchasers would no longer reasonably expect a person or group to carry out essential managerial or entrepreneurial efforts—the assets may not represent an investment contract.” Director Hinman elaborated by explaining that “when the efforts of the third party are no longer a key factor for determining the enterprise’s success, material information asymmetries recede,” and as the network becomes decentralized, “the ability to identify an issuer or promoter to make the requisite disclosures becomes difficult, and less meaningful.”

Rensel v. Centra Tech, Inc., et al., Case No. 17cv-24500-RNS (S.D. Fla. June 25, 2018)

Centra Tech, Inc. (“Centra Tech”) billed itself as “the world’s first debit card that is designed for use with compatibility on 8+ major cryptocurrencies blockchain assets.” In particular, Centra Tech proposed to be the first company to provide a bridge between the cryptocurrency industry and the general retail world by allowing individuals to pay for goods and services with cryptocurrency through a common debit card. Between July 30, 2017 and October 5, 2017, Centra Tech conducted a token sale to raise capital for further development of the Centra Debit Card and Centra Wallet. It also claimed to be planning development of an online marketplace referred to as cBay. During its token sale, Centra Tech offered a token to the public that would be necessary to use the Centra Card or Centra Wallet. Criminal charges have been filed against Centra Tech’s founders, and the SEC has filed an enforcement action against the founders and/or officers of Centra Tech, alleging securities (and other) fraud arising out of the token sale. The SEC also recently settled charges against professional boxer Floyd Mayweather, Jr. and music producer Khaled Khaled (a/k/a DJ Khaled) in November 2018 for failing to disclose payments that they received for promoting Centra Tech’s token sale, in violation of Section 17(b) of the 1933 Act.

Meanwhile, participants in the sale filed a securities class action against Centra Tech and its officers and founders, alleging that the Centra Tech token sale was an unregistered offering and sale of securities in violation of Sections 5 and 12(a) of the 1933 Act, and that the individual defendants were liable as control persons under Section 15 of the 1933 Act. Plaintiffs moved for a temporary restraining order to, among other things, prevent defendants from transferring or dissipating the token sale proceeds. Defendants disputed that the Centra Tech token was a security but did not raise the argument for purposes of the motion. The Magistrate Judge concluded that the Centra Tech token was an investment contract and, therefore, a security under the federal securities laws. Specifically, the Magistrate Judge concluded: “The Plaintiffs’ investment of assets, in the form of Ether and/or Bitcoin, satisfies the ‘investment of money’ prong for an investment contract.” As to the second prong of the Howey test (common enterprise), the Magistrate Judge explained: “The fortunes of individual investors in the Centra Tech ICO were directly tied to the failure or success of the products the Defendants purported to develop. An individual investor could exert no control over the success or failure of his or her investment. Thus, the Plaintiffs have established the existence of a common enterprise.” Although the Magistrate Judge did not squarely focus on whether token purchasers expected to profit from their purchases, the Magistrate Judge concluded that the tokens also satisfied Howey’s third and fourth prongs (expectation of profits based solely on the efforts of others) because the entire enterprise that Centra Tech “purported to develop was entirely dependent on the efforts and actions of the Defendants.” Because the tokens were not registered and did not qualify for an exemption from registration, the Magistrate Judge concluded that plaintiffs had established a probability of success in proving that the token sale constituted an unregistered offering of securities in violation of the securities laws. Because plaintiffs also showed that they would suffer irreparable harm if the temporary restraining order were not granted, the Magistrate Judge recommended that the temporary restraining order be issued.

Subsequently, the district court adopted the Magistrate Judge’s report and recommendation to the extent that it pertained to funds raised in the token sale. Plaintiffs filed an amended complaint in October 2018, alleging violations of Section 5 and 12(a) of the 1933 Act and Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 of the 1934 Act, and certain defendants moved to dismiss on December 21, 2018. A decision on the motions to dismiss is expected in early 2019. Other defendants, including Centra Tech, did not respond to the complaint, and default judgments were entered as to those defendants in January

2019.

United States v. Zaslavskiy, Case No. 17-cr-647- RJD, 2018 WL 4346339 (E.D.N.Y. Sept. 11, 2018)

Maksim Zaslavskiy was indicted for securities fraud and conspiracy to commit securities fraud connection with two token sales: one conducted by REcoin Group Foundation, LLC (“REcoin”), which Zaslavskiy founded; and one conducted by Diamond Reserve Club (“Diamond”). REcoin purportedly engaged in real estate investment and the development of real estate-related smart contracts. Diamond purportedly invested in diamonds and obtained discounts from diamond retailers for Diamond members. The U.S. Department of Justice alleges that between January to October 2017, Zaslavskiy fraudulently induced investors to purchase tokens in connection with the REcoin and Diamond token sales by offering “investment opportunities” based on materially false statements. REcoin never purchased any real estate, no REcoin token ever was developed, and REcoin investors received no tokens. Likewise, Diamond never purchased any diamonds, no Diamond tokens ever were developed, and Diamond investors received no tokens.

Zaslavskiy moved to dismiss the indictment, arguing that the REcoin and Diamond token sales did not involve securities and, consequently, were beyond the reach of the federal securities laws. The Government argued that the investments made in REcoin and Diamond were investment contracts under the Howey test and, therefore, securities as defined by the federal securities laws.

The district court found that whether a “transaction or instrument”—particularly a novel transaction or instrument such as a digital token—“qualifies as an investment contract is a highly fact-specific inquiry.” The district court held that a reasonable jury could conclude that the facts alleged in the indictment satisfied each element of the Howey test, because the facts alleged suggested that purchasers invested money to participate in Zaslavskiy’s alleged schemes for the purpose of sharing pro-rata in the schemes’ profits, and such profits were expected to be derived solely from Zaslavskiy’s and his co-conspirators’ efforts. The court also concluded that the federal securities laws were not unconstitutionally vague as applied to Zaslavskiy: “The Indictment describes REcoin and Diamond as schemes devised by Zaslavskiy and his co-conspirators to use the money of others on the promise of profits. The [federal securities laws] are intended to prevent just that: their aim is to protect the American public from speculative or fraudulent schemes of promoters like Zaslavskiy and ensure full and fair disclosure with respect to securities. . . . The Indictment plainly alleges that REcoin and Diamond were two of the countless and variable schemes that in the ever-evolving commercial market, fall within the ordinary concept of a security. At this juncture, Zaslavskiy’s contrary characterizations are plainly insufficient to by-pass regulatory and criminal enforcement of the securities laws.”

Zachary Coburn, Securities Exchange Act Release No. 84553 (Nov. 8, 2018)

On November 8, 2018, the SEC announced that it had settled charges against Zachary Coburn, the founder of EtherDelta, a digital token trading platform. This was the SEC’s first enforcement action based on findings that such a platform operated as an unregistered national securities exchange. EtherDelta provided a marketplace for pairing buyers and sellers of digital assets through the combined use of an order book, a website displaying orders, and a smart contract run on the Ethereum blockchain. The smart contract was coded to validate order messages, confirm terms and conditions of orders, execute paired orders, and direct the distributed ledger to be updated to reflect trades. The SEC found that over an 18-month period, EtherDelta’s users executed more than 3.6 million orders for tokens, including unidentified tokens that constituted securities under the federal securities laws. Without admitting or denying the SEC’s findings, Coburn settled with the SEC, and agreed to pay $300,000 in disgorgement, $13,000 in prejudgment interest, and a $75,000 civil penalty. The SEC’s investigation concerning the matter is ongoing.

Paragon Coin, Inc., Securities Act Release No. 10574 (Nov. 16, 2018)

On November 16, 2018, the SEC announced that it had settled charges against two companies that conducted unregistered tokens sales in 2017, including Paragon Coin, Inc. (“Paragon”). Paragon’s token sale raised approximately $12 million in digital assets to develop and implement a business plan to add blockchain technology to the cannabis industry and work toward legalization of cannabis. The settlements included three primary components. First, without admitting or denying the SEC’s findings, each company was required to pay a civil penalty of $250,000. Second, within 90 days of the settlement, each company is required to register its tokens as securities under Section 12(g) of the 1934 Act and maintain such registration for at least one year. Third, each company is required to conduct a claim process which will allow token purchasers to seek a refund of their purchases.

SEC v. Blockvest, LLC, et al., Case No. 18-cv-2287-GPB, 2018 WL 6181408 (S.D. Cal. Nov. 27, 2018)

Blockvest, LLC (“Blockvest”) was established to function as a cryptocurrency exchange, but has not become operational. Blockvest allegedly conducted a “pre-sale” of tokens in March 2018. Blockvest allegedly represented that its token sale was registered and approved by the SEC, and used the SEC’s seal on its website. Blockvest claims that it never actually sold any tokens, but rather, conducted testing of its platform by accepting funds from 32 “testers.” The SEC brought an enforcement action against Blockvest and its officers and founders, asserting claims under Sections 5 and 17 of the 1933 Act, and Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 of the 1934 Act. The SEC moved for a preliminary injunction seeking to freeze defendants’ assets. The district court denied the SEC’s motion, concluding that the SEC had not established a prima facie violation of federal securities laws because the SEC had not carried its burden of showing that Blockvest’s tokens were securities. In particular, the district court concluded that the parties’ competing evidence of what, if anything, the 32 testers “relied on, in terms of promotional materials, information, economic inducements or oral representations . . . before they purchased the test . . . tokens” precluded the court from determining that the testers had “invested” money, as required under Howey’s first prong. Nor did the district court find any evidence in the record supporting the SEC’s assertion that the testers expected to profit, as required under Howey’s second prong.

On February 14, 2019, however, the district court granted the SEC’s motion for partial reconsideration. Setting aside what the 32 testers relied on, the district court held that the SEC had alleged more broadly a prima facie violation of Section 17 of the 1933 Act. In particular, focusing on the breadth of the term “offer” in the 1933 Act, the district court held that the SEC had alleged that Blockvest “offered” unregistered securities through allegedly misleading promotional materials that Blockvest had posted on its website and through social media accounts. With respect to the Howey test, the district court concluded that the promotional materials satisfied Howey’s first prong because they asked investors to provide digital currency in exchange for tokens. The district court also concluded that Howey’s other elements were satisfied because the promotional materials promoted a common enterprise through which “passive” investors expected to profit. Based largely on these conclusions, the district court preliminarily enjoined defendants from violating Section 17(a) of the 1933 Act, and certain defendants moved to dismiss on December 21, 2018. A decision on the motions to dismiss is expected in early 2019. Other defendants, including Centra Tech, did not respond to the complaint, and default judgments were entered as to those defendants in January 2019.

Cases to Watch

In re Tesla, Inc. Securities Litigation, Case No. 3:18-cv-04865-EMC (N.D. Cal.)—Statements Concerning Go-Private Transaction

As noted, Tesla, Inc. designs, develops, manufactures, and sells high-performance electric vehicles and solar energy generation and energy storage products. On August 7, 2018, the Twitter handle associated with Tesla’s CEO sent a series of tweets concerning a take-private transaction involving Tesla, including: “Am considering taking Tesla private at $420. Funding secured.”; “I don’t have a controlling vote now & wouldn’t expect any shareholder to have one if we go private. I won’t be selling in either scenario.”; “My hope is *all* current investors remain with Tesla even if we’re private. Would create special purpose fund enabling anyone to stay with Tesla. Already do this with Fidelity’s SpaceX investment.”; “Shareholders could either to sell [sic] at 420 or hold shares & go private.”; and “Def no forced sales. Hope all shareholders remain. Will be way smoother & less disruptive as a private company. Ends negative propaganda from shorts.” Trading volume in Tesla stock rose to 30 million shares that day, and Tesla stock price rose to an intraday high of $387.46/share, approximately $45 above the prior trading day’s closing price. Later that day, Tesla’s CEO reaffirmed that he was contemplating a take-private transaction for $420/ share, and that “Investor support is confirmed. Only reason why this is not certain is that it’s contingent on a shareholder vote.”

Beginning on August 10, 2018, several investors filed class action complaints, claiming that Tesla and its CEO made false and misleading statements that Tesla had secured funding to take the company private, in violation of Sections 10(b) and 20(a), and Rule 10b-5. A consolidated complaint was filed in January 2019. Defendants’ motions to dismiss are due to be filed in March 2019, and are scheduled to be heard in June 2019.

Lopes v. Fitbit, Inc., et al., Case No. 3:18-cv-06665-JST (N.D. Cal.)—Reduced Revenue Projections

Fitbit, Inc. (“Fitbit”) is a technology company focused on health-related devices including wearable health and fitness activity trackers. In an August 2016 earnings release, Fitbit projected that its revenue for the full year of 2016 would be in the range of $2.5 to $2.6 billion. During a conference call the same day, Fitbit’s officers explained that Fitbit continued to be the leader in the worldwide wearable market by units as of the end of the first quarter of 2016, and that Fitbit saw opportunities to continue expanding its market share in the U.S., including by potentially attracting customers who also used smartphones. During an October 2016 interview with Jim Cramer on CNBC, Fitbit’s CEO differentiated the company from Apple, Inc., explaining that Fitbit is a fitness social network coupled with hardware. In November 2016, Fitbit issued an earnings release in which it lowered its full year 2016 revenue guidance to between $2.32 and $2.345 billion, representing growth of approximately 25-26%, and fourth quarter revenues of between $725 and $750 million. Thereafter, in January 2017, Fitbit announced its preliminary fourth quarter 2016 financial results, stating that its anticipated fourth quarter revenues were approximately $572 to $580 million, and that its annual revenue growth for the full year of 2016 was anticipated to be 17%, not 25-26%.

Shareholders filed a federal securities class action against Fitbit and its officers, asserting claims under Sections 10(b) and 20(a), and Rule 10b-5. Plaintiffs allege that Fitbit made materially false and misleading statements about the company’s mission and attempts to differentiate itself from Apple, the competition that Fitbit was facing, and Fitbit’s operations, business, financial results and prospects. A lead plaintiff is expected to be appointed in early 2019, and an amended complaint likely will be filed thereafter.

In re Alphabet Securities Litigation, Case No. 4:18-cv-06245-JSW (N.D. Cal.)—Data Breach

Alphabet, Inc. (“Alphabet”), the parent company of Google, is a multinational technology conglomerate that is a holding company of several former Google subsidiaries. Among its products are web-browser Google, webmail Gmail, and the now defunct social media platform Google+. Google discovered a software glitch in the application programming interface in Google+ which exposed hundreds of thousands of users’ personal data in spring 2018, but did not disclose the breach at that time. In the fall of 2018, the Wall Street Journal reported on the software glitch and data breach. Citing an internal Google memorandum, the Wall Street Journal stated that Google had not disclosed the data breach in part because of concerns about drawing regulatory scrutiny and suffering reputational damage. Subsequently, Google’s stock price declined by nearly 6%. Thereafter, Google announced plans to shut down Google+.

Shareholders filed federal securities class action complaints against Alphabet and its officers, alleging that between the discovery of the breach and its announcement, defendants made materially false and misleading statements regarding the extent of the breach and users’ data security in violation of Sections 10(b) and 20(a) and Rule 10b-5 of the 1934 Act. The district court consolidated the lawsuits and appointed a lead plaintiff in January 2019. A consolidated complaint is expected to be filed in early 2019.

In re Intel Corporation Securities Litigation, Case No. 4:18-cv-00507-YGR (N.D. Cal. Jan. 23, 2018)—Alleged Design Flaw

Intel Corporation (“Intel”) designs and manufactures computer components, including microprocessors, chips, digital imaging products, and systems management software. On January 2, 2018, news outlets reported a design flaw in Intel’s processor chips that could make a computer’s operating system vulnerable to outside attacks. The online publication The Register reported that the operating system updates necessary to address this flaw would result in a significant slowdown for Intel-based computing devices. The next day, media outlets further reported that Google’s security team had discovered further flaws affecting computer processors built by Intel. That same day, Intel published a release on its website confirming that its chips contain a feature making them vulnerable to hacking. Further, on January 4, 2018, the media reported that Intel’s CEO sold $24 million worth of Intel stock and options in late November 2017, allegedly after Intel was informed of the security flaws in its semiconductors but before such flaws were publicly disclosed.

On January 23, 2018, investors filed a securities class action against Intel and its officers under Sections 10(b) and 20(a) and Rule 10b-5, alleging that defendants made false or misleading statements concerning the company’s products’ vulnerabilities. A lead plaintiff was appointed in May 2018, and a consolidated complaint was filed in July 2018. On November 13, 2018, defendants moved to dismiss the consolidated complaint, arguing that: (1) defendants made no false or misleading statements about security vulnerabilities; (2) the complaint fails to allege specific facts giving rise to a strong inference of scienter, as required under the PSLRA; and (3) the complaint fails to state a claim for control-person liability because it does not allege a viable underlying violation. A hearing on the motion to dismiss has been scheduled for March 19, 2019.

In re Oracle Corporation Securities Litigation, Case No. 5:18-cv-04844-BLF (N.D. Cal.)—Slowed Cloud-Related Revenue Growth

Oracle Corporation (“Oracle”) is a software company that develops database software and technology, cloud engineered systems, and enterprise software products, offering on-premise and cloud solutions to a variety of end users. Historically, Oracle’s revenues were derived from the company’s on-premise software services, but in 2015 the company shifted its focus to cloud services as cloud storage. Throughout 2017, the company made public statements at conferences and through press releases that reported significant increases in cloud-related revenues. On September 14, 2017, Oracle issued

a press release announcing that results for its first fiscal quarter ended August 31, 2017 were “up 51% to $1.5 billion.” On September 18, 2017, Oracle filed a Form 10-Q attributing its cloud revenue growth to “increased. . . investments in and focus on the development, marketing and sale of our cloud-based applications, platform and infrastructure technologies.” The company made similar statements promoting the cloud business at an October 5, 2017 OpenWorld Financial Analyst conference, and on December 14, 2017, Oracle issued a press release stating that cloud revenues were “up 44% to $1.5 billion.” Thereafter, on March 19, 2018, the company disclosed that cloud revenue growth had stagnated and forecasted significantly slower sales growth for its cloud business relative to its competitors. Following the announcement, Oracle’s stock price declined by nearly 9.5%, representing the Company’s largest single-day stock drop in more than five years.

Investors filed a federal securities class action against Oracle and its officers, asserting claims under Sections 10(b) and 20(a) and Rule 10b-5. Plaintiffs allege that defendants made misrepresentations regarding revenue growth within Oracle’s cloud segment. Plaintiffs further allege that Gartner, Inc., “a leading research and advisory company. . . observed that Oracle had to rely on coercive practices because its cloud-based offering is a ‘bare-bones minimum viable product.’” The complaint includes allegations that Oracle’s cloud revenues were driven by unsustainable and coercive practices, including: (1) audits of customers’ use of non-cloud software licenses and “levying expensive penalties against those customers”; (2) “decreasing customer support . . . in an effort to drive customers . . . into cloud-based systems”; and (3) “strong-arming customers by threatening to dramatically raise the cost of legacy database licenses if the customers choose another cloud provider.”

In re Facebook, Inc. Securities Litigation, Case No. 5:18-cv-01725 (N.D. Cal) —Data Access of Disclosure

Facebook, Inc., (“Facebook”) operates a social networking website. Between 2016 and early 2018, Facebook warned in its SEC filings that “[s]ecurity breaches and improper access to or disclosure of our data or user data, or other hacking and phishing attacks on our systems, could harm our reputation and adversely affect our business.” During the same time, Facebook maintained a data privacy policy, which stated that “Your trust is important to us, which is why we don’t share information we receive about you with others unless we have: received your permission; given you notice, such as by telling you about it in this policy; or removed your name and any other personally identifying information from it.” Thereafter, beginning in March 2018, media reports stated that a political consulting firm, Cambridge Analytica, gathered personal information of 50 million Facebook users from Facebook without permission or proper disclosures. Further reports of U.S. and foreign government investigations into the matter followed, and Facebook’s stock price declined.

Investors filed securities class action lawsuits against Facebook and its officers, alleging that defendants made materially false and/or misleading claims about Facebook’s handling of user data in violation of Sections 10(b) and 20(a), and Rule 10b-5. A lead plaintiff was appointed on August 3, 2018, and a consolidated amended complaint was filed on October 15, 2018. Defendants moved to dismiss the consolidated amended complaint on December 14, 2018, arguing that plaintiffs have not adequately alleged any materially false misstatements or omissions, scienter, reliance, or loss causation. The motion to dismiss is scheduled to be heard in April 2019.

Endnotes

1Source: Cornerstone Research Securities Class Action Filings – 2018 Year in Review (“Cornerstone Report”), at 1.(go back)

2Cornerstone Report, at 1.(go back)

3Cornerstone Report, at 34 and Appendix 7. Sectors and subsectors are based on the Bloomberg Industry Classification System.(go back)

4Cornerstone Report, at 12.(go back)

5Cornerstone Report, at 36.(go back)

6Cornerstone Report, at 35 and Appendix 8.(go back)

Print

Print