Michelle Greene is President of the Long-Term Stock Exchange. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Toward Fair and Sustainable Capitalism by Leo E. Strine, Jr. (discussed on the Forum here).

Being a stakeholder-focused company means upping the influence of workers, customers, the community and others critical to long-term success

The leaders from the worlds of business and finance who descended on Davos for The World Economic Forum’s latest annual gathering left the mountain resort after four days of discussion devoted to giving concrete meaning to stakeholder capitalism.

Now that the panels are over, how can these paragons of capitalism realize the ambitions they set at the Swiss resort? The gathering followed a year that saw nearly 200 members of the Business Roundtable pivot from the group’s decades-long “shareholder primacy” doctrine to one that demands the interests of stakeholders be considered. From the “new paradigm” proposed by Martin Lipton to the “Embankment Project” propounded by Ernst & Young and the Coalition for Inclusive Capitalism, the calls for reimagining capitalism continue to grow.

As the attention paid by these leaders suggest, shareholder primacy, as practiced for the past several decades, has become untenable. Inequality is at historic and unsustainable levels. From 1978 to 2018, CEO compensation grew by nearly 1000 percent; the compensation of a typical worker, meanwhile, rose just 12 percent. Even CEOs overwhelmingly see the need for change, with nearly 90 percent in a recent UN Global Compact—Accenture survey believing that “our global economic systems need to refocus on equitable growth.” From privacy breaches to outsized political influence to environmental degradation, corporations’ contributions to societal problems are being laid bare.

At the same time, policymakers are increasingly unable or unwilling to address the scope of challenges facing our communities—and some corporations wield greater power and influence than governments.

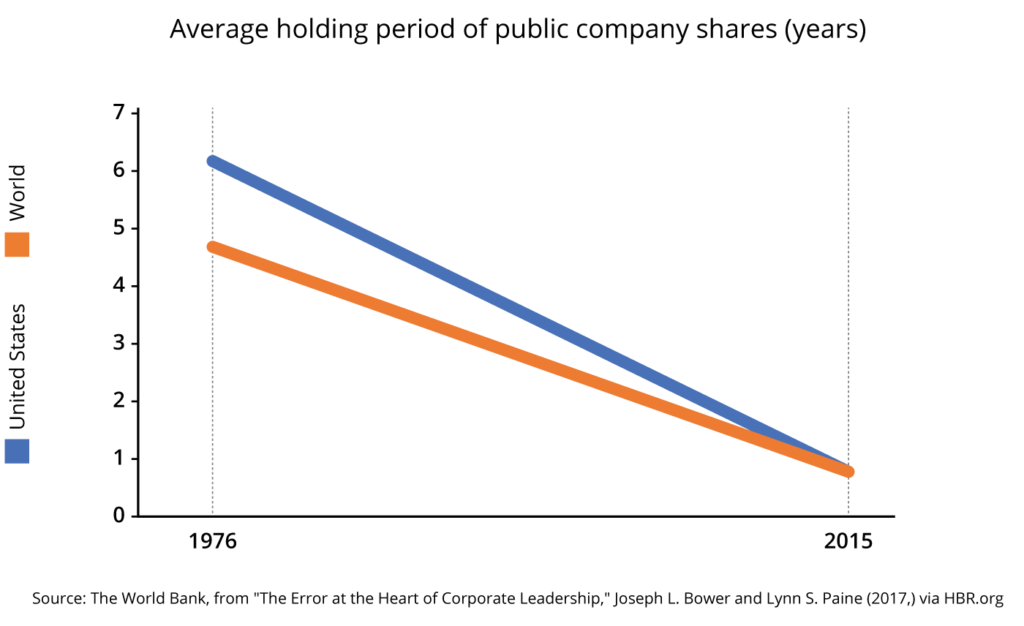

Capital markets and many shareholders themselves warp the incentives. The average holding period for U.S. public company shares has plummeted, from 5.1 years in 1976 to 7.4 months in 2015.

Public markets have become so short-term focused that companies that aim to innovate and succeed for generations must fight against a pervasive quarterly cadence. Academics, market participants, and commentators all have voiced concern regarding “short-termism” and the risk that a focus by some investors on short term results can pressure companies to sacrifice long-term value creation in order to satisfy quarterly or other short-term expectations. Eighty-percent of chief financial officers of public companies acknowledge they would forego initiatives such as research and development in order to avoid missing quarterly targets, according to one study. Another found that companies projected to just miss their earnings are significantly more likely to repurchase shares than companies that beat their EPS forecasts by a few cents, suggesting efforts to increase EPS through financial engineering rather than growth. In the calendar year following repurchases, those same companies decreased the size of their workforce, investment in research and development, and capital expenditures. Declines in both the number of public companies and the holding periods of public company shares by institutional investors have been well documented.

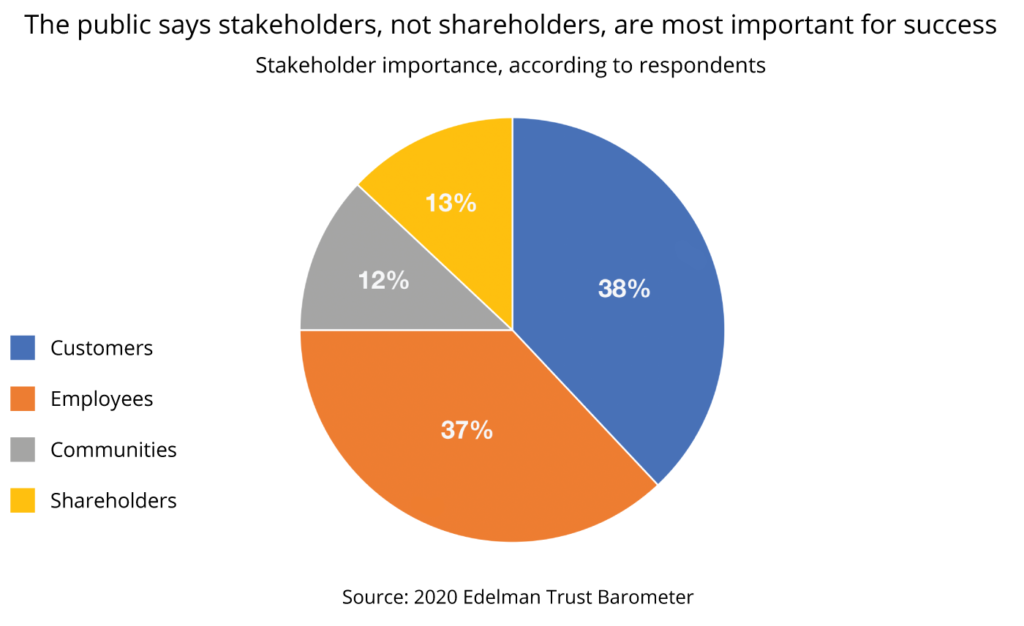

All of this has given rise to the growing primacy of stakeholder-focused companies. Consumers, workers, and communities, with millennials in the vanguard, increasingly are holding corporations to higher and broader standards of responsibility. According to Edelman’s most recent Trust Barometer survey, 87 percent of the public believes that stakeholders are more important to companies’ long-term success than shareholders.

Modern companies embrace their obligations to do right by all of their stakeholders—including employees, customers, suppliers, communities, and long-term shareholders—and recognize the opportunity it provides. The key to sustainable success is to increase the power and influence of all of a company’s primary stakeholders; the people who have their own “skin in the game” for the company’s long-term well-being.

These stakeholders care far more about investing in the future of the company—including investing in human capital and innovation—than in cutting corners or engaging in financial gymnastics to meet quarterly targets. They will support boards and executives in making the hard choices that are right for future growth, even if they are painful for right now. Those same stakeholders provide a counterbalance to short-term activism while reinforcing accountability for results.

Giving stakeholders a voice

But how do companies actually maintain a strong stakeholder focus? First, it requires understanding who key stakeholders are and why they are important. For every company, employees, customers and long-term shareholders are obvious. But what about non-employee workers? The community in which a company operates? The environment more broadly? Our democracy? Arguably any of these could count. While different stakeholder groups may require different levels of engagement, key ones should have a role—or at least a meaningful voice—in governance.

One approach is for companies to ensure that their most critical stakeholders are also shareholders. Companies can provide equity to all employees—and could broaden equity grants to include others as well. Think, for example, about the importance of drivers to Lyft or Uber, which both had programs at IPO to provide bonuses that facilitated the purchase of shares by certain drivers. The relationship is reciprocal, and these contributors are deeply vested in the companies’ ongoing success. Certain thresholds of engagement could trigger share ownership. Companies could use their capital structure to increase the influence of these special stakeholder-shareholders, either by reimagining dual-class share structures or creating a new form of time-phased voting.

Dual-class structure can be used to create corporate dictatorships, but instead companies could use it to create a democracy of the citizens—giving those with the greatest interest in the company’s long-term success more say in governance by granting them shares with greater voting rights. Of course, dual class is not required to achieve this. Companies can create a single class of common shares with differentiated voting rights. Tenured voting exists today, but this could be a more accessible, egalitarian version. Voting rights could be similarly based on holding periods, and companies could provide the formulas for when the tenure begins based on stakeholder class. This elevated status should be offered to truly long-term shareholders as well, aligning increased voting power with the groups that have the greatest interest in the company’s sustainable success.

Giving stakeholders a seat at the table

Direct stakeholder engagement starts at the top. This past spring, Walmart hourly workers pushed for a seat on the company board. Although that shareholder vote failed, several pieces of legislation have been introduced in the U.S. Congress to provide for employees to elect and/or serve as directors of the companies that employ them. In many European countries, such representation is required.

Board representation provides a direct voice, and need not be limited to workers. Studies show how such representation can provide benefits and valuable perspectives to the directors. A related alternative is fiduciary representation, where the group (e.g., workers) creates a trust, and a trustee representative, who owes a fiduciary obligation to the group members, holds a board seat. Some companies might prefer to provide special proxy access, allowing workers and/or other stakeholder groups to nominate a set percentage of board members.

Even if stakeholders don’t have special influence in director elections, board structure can ensure their interests are represented. Airbnb has announced a number of critical steps in stakeholder focus, including creating a stakeholder committee of the board. Another approach is to have each director designated to represent the perspective of one group of stakeholders—such as employees, non-employee workers, community members or the environment. The director would be expected to engage regularly and develop relationships with her group. So, for example, the community-focused board member would have a pulse on local concerns, relationships and lines of communication with community leaders and policymakers, and the ability to provide community perspective on company decisions, with a commitment to preemptively raise concerns and seek solutions. Another option is for board members to hold open office hours.

Many companies already have advisory boards, another way to engage key groups. Creating them is not enough, however. Advisory boards need meaningful avenues of communication to provide their perspectives to directors and, ideally, the opportunity to weigh in on key decisions. Stakeholder advisory boards might even be provided a formal avenue to appeal adverse corporate decisions. And the input of advisory boards should extend to management as well.

From the boardroom to the C-suite (and beyond)

Indeed, executives must also engage directly and effectively with all key stakeholder groups, starting with workers. Employees increasingly are yielding influence on a broader array of company issues through social media campaigns, internal organizing, and protests. Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook, Google and many others have faced worker petitions and protests regarding company actions, from engaging with oil and gas suppliers to sexual harassment policy. One Google protest involved 20,000 employees around the world. Employees shouldn’t need to literally yell and hold up signs to have their voices heard. Companies can create channels for meaningful collaboration that can help them better understand employee concerns and priorities, preempting the need for disruptive action and fostering trust. Such communication can surface issues that management should be addressing, but may not see as readily as those on the front lines.

Executives should seek systemic input from other key stakeholders as well. Options for meaningful engagement include joint management-stakeholder working groups with actual authority on particular issues or standing joint committees with direct lines into the executive team. Some companies hire an ombudsperson. This employee of the company sits on key executive and leadership teams, but her role is to be closely aligned with and represent the perspectives of community members—be they employees, non-employee workers, customers or members of the physical community. In addition, to ensure that individuals are heard, companies can create mechanisms for any member of a key stakeholder class to provide feedback or ideas. Companies hold annual meetings for shareholders, why not for stakeholders as well?

Under federal law, environmental impact statements are required for major actions with potential adverse consequences. State and local policymakers often require a similar analysis for development projects. This approach can be adapted by companies to provide for stakeholder impact statements prior to major company actions likely to have significant impact on workers, the community or other stakeholders. The analysis can be conducted in a way that enables stakeholders to weigh in. The goal: to ensure that a broad set of relevant interests is directly considered in company decision-making.

Whichever of these approaches a company chooses, the provisions must be robust enough to ensure that the voice of core stakeholders influences both the boardroom and C-suite, and that institutional mechanisms ensure that their perspectives will be respected and incorporated beyond the tenure of any one leadership team.

Of course, innovative ways to engage stakeholders in company governance and decision-making go far beyond this list. None of these actions is simple. Changing a status quo that benefits powerful segments of society rarely is. Giving true voice to stakeholders will be complicated and undoubtedly create inefficiencies, challenges, and discomfort. But modern companies recognize that today’s capitalism is obsolete.

For a visionary company to protect its mission and values over the long term, its governance must institutionalize a commitment to those who make its success possible. By adopting a series of governance innovations, companies can create meaningful obligations to do right by their most important stakeholders. It doesn’t get much more concrete than that.

Print

Print