Richard Alsop is a partner and Yoon-jee Kim is an associate at Shearman & Sterling LLP. This post is based on their Shearman & Sterling memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Social Responsibility Resolutions by Scott Hirst (discussed on the Forum here).

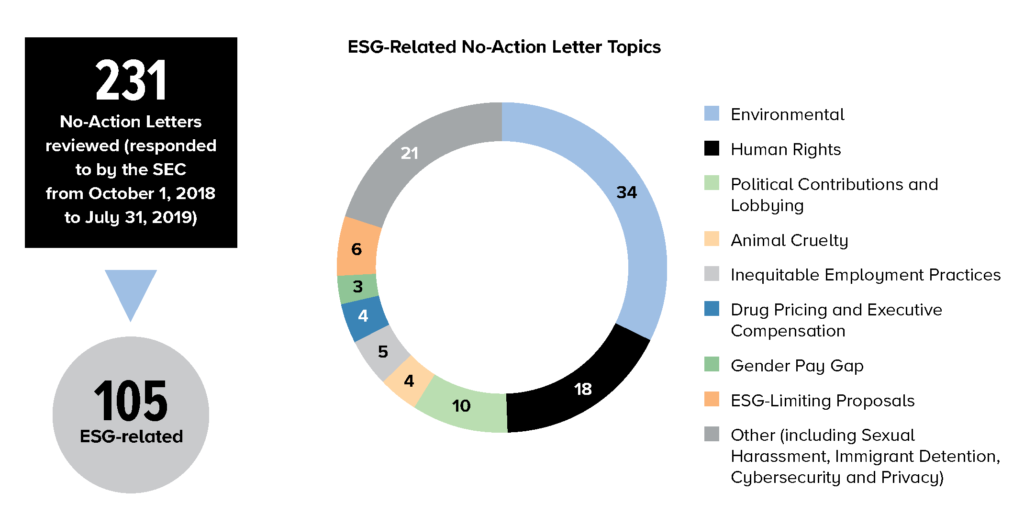

Shareholder proposals relating to ESG matters are frequent targets for exclusion by companies, and based upon a survey of the no-action letters submitted during the 2019 proxy season, this trend continues. Over 40% of the no-action letters we reviewed for the 2019 proxy season related to a variety of ESG matters, and the arguments and outcomes in those letters are instructive as to how companies and the SEC staff are approaching ESG proposals, especially in the wake of recent SEC staff guidance on its approach to requests based on the “economic relevance” (Rule 14a-8(i)(5)) and “ordinary business” (Rule 14a-8(i)(7)) exemptions, which are frequently cited grounds for excluding ESG-related shareholder proposals. [1] In terms of the subject matter of proposals for which exclusion was sought, the largest group related to environmental matters, sustainability and climate change, accounting for 34 out of the 105 ESG-related no-action letters we reviewed. Human rights issues also continued to appear as the subject of numerous proposals for which no-action letters were submitted, accounting for 18 no-action letters. Other shareholder proposal topics giving rise to no-action letters included topics such as political contributions and lobbying (ten), animal cruelty (five), drug pricing (four) and proposals relating to inequitable employment practices and the gender pay gap (eight). Other proposal topics that spawned no-action letters included “me too,” hate speech, immigrant detainees, diversity and privacy.

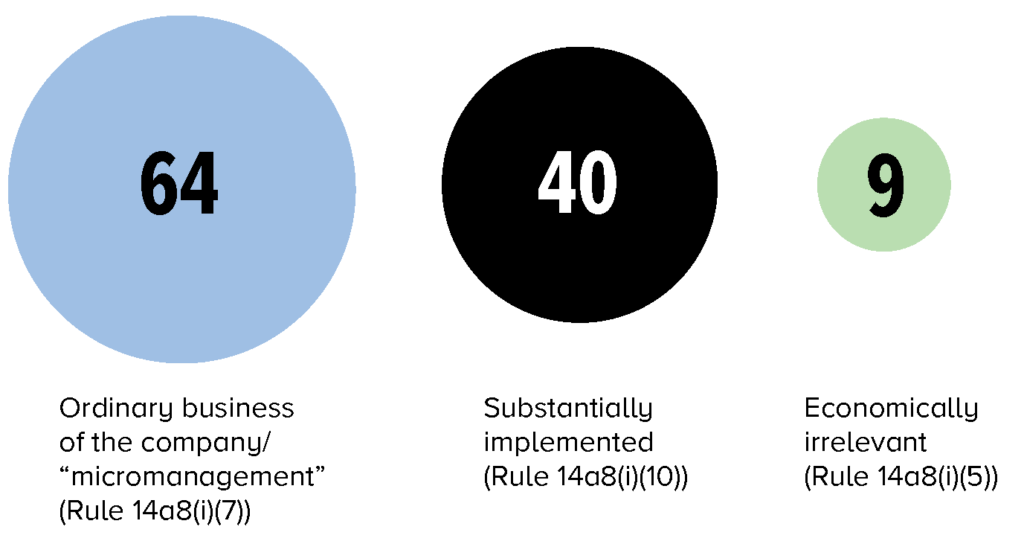

ESG-Related No-Action Letters: Bases for Exclusion*

Further patterns emerged in the approaches issuers took to exclude ESG-related proposals. The most common bases for requesting exclusion (setting aside technical bases such as the failure to meet the conditions of Rule 14a-8 or duplicating other proposals) were that the proposal:

- related to the ordinary business of the company or micromanaged the company (Rule 14a-8(i)(7))

- that it had been substantially implemented (Rule 14a-8(i)(10)) or

- was economically irrelevant (Rule 14a-8(i)(5))

*Many companies use multiple bases of exclusion in their no-action letter requests.

SEC Staff Guidance on “Economic Relevance” and “Ordinary Business”

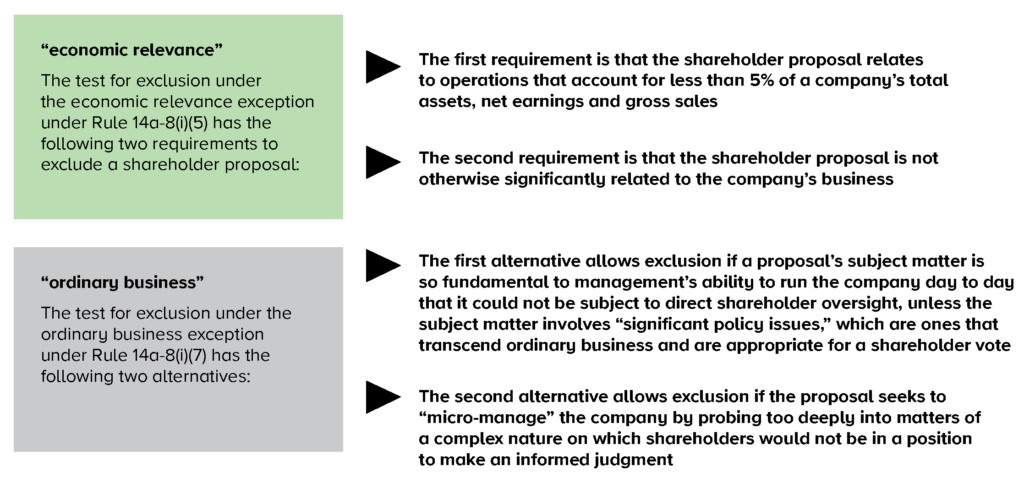

The SEC published Staff Legal Bulletin 14I (SLB 14I) in November 2017, and, after one proxy season of experience with it, published Staff Legal Bulletin 14J (SLB 14J) in October 2018. This guidance applies to the tests for exclusion under the economic relevance exception under Rule 14a-8(i)(5) and the exclusion for ordinary business under Rule 14a-8(i)(7), which are summarized below:

Prior to SLB 14I, the SEC staff took a more direct role in determining whether a proposal related to a significant policy issue. In doing so, the SEC staff considered a number of factors, including the degree of public attention given to an issue, press and other media coverage and legislative or regulatory activity, which were referenced by proponents to support their arguments. In SLB 14I, the SEC staff indicated that it believes a company’s board is “well situated to analyze and determine and explain whether a particular issue is sufficiently significant” to prevent exclusion under the economic relevance or ordinary business exceptions. To that end, the SEC staff indicated that it would expect to see a discussion of the specific processes employed by the board to assess whether the issue transcends its ordinary business operations or if the issue is significantly related to its business.

After the SEC staff issued SLB 14I, there was speculation that a discussion of the board’s analysis and consideration of the subject matter of a shareholder proposal might lead to more exclusions based on economic relevance or ordinary business, based on deference to the judgment of the board. However, it was not at all clear after the 2018 proxy season that the SEC staff’s new approach in SLB 14I had resulted in measurable benefits for companies and proponents in terms of more clarity in the process. Virtually every proposal submitted on economic relevance during the 2018 proxy season or ordinary business grounds included a discussion of the process and analysis performed by the board or a committee. However, the outcomes indicated that the SEC staff did not really defer to the determination of the board on policy issues, particularly where the SEC staff had historically taken a consistent position on social policy issues like political contributions and lobbying. The SEC staff also seemed to give more weight to significant shareholder support in a prior shareholder vote on the same matter than to any analysis and determination by the board. [2]

In SLB 14J, the SEC staff discussed board analyses again, noting that in the 2018 proxy season, the most helpful board analyses discussed not only the process followed by the board and the board’s conclusions, but also the substantive factors that the board took into consideration. SLB 14J stated that the SEC staff continues to believe that a well-developed discussion of the board’s analysis of whether the particular policy issue raised by the proposal is “otherwise significantly related to the company’s business,” in the case of Rule 14a-8(i)(5), or is “sufficiently significant” in relation to the company, in the case of Rule 14a-8(i)(7), can assist the staff in evaluating a company’s no-action request. SLB 14J notes that the absence of a board analysis will not create a presumption against exclusion, but that the absence of the board’s insights may make it more difficult for the SEC staff to agree that a proposal may be excluded.

SLB 14J enumerated some of the substantive factors considered by the board that might be discussed in a well-developed board analysis, including:

- The extent to which the proposal relates to core business activities

- Quantitative data, including financial statement impact, related to the matter that illustrates whether or not it is significant to the company

- Whether the company has already taken action on the subject matter, and if so, the differences between the proposal and the action taken and an analysis of whether the differences present a significant policy issue

- The extent of shareholder engagement and interest

- Whether anyone other than the proponent has requested the type of action sought by the proposal

- Whether the shareholders have previously voted on the subject matter and the board’s views as to the related voting results

With respect to prior shareholder votes, SLB 14J states that the SEC staff would expect any board discussion to adequately address the voting results. The SEC staff will consider the discussion of previous shareholder votes as part of the total mix of information relating to the proposal, and the weight given to such votes will depend on the specific facts and circumstances. Where a previous proposal received significant support, the SEC staff will consider intervening events or actions by the company that may have mitigated the significance of the issue. Where a previous proposal received insignificant support, the SEC staff will consider whether intervening events or actions may have increased the significance of the proposal. Lastly, the time elapsed since the previous vote will be considered, with a more recent vote being more relevant to the analysis.

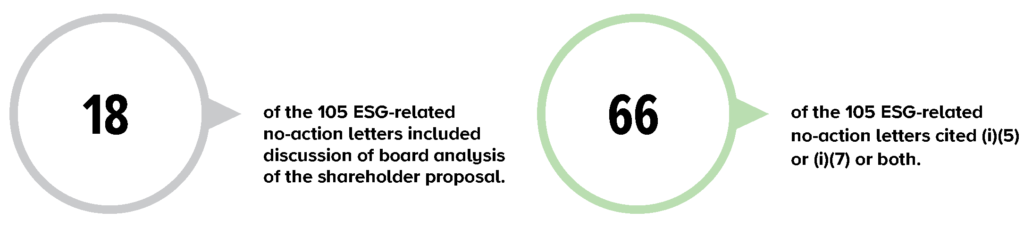

After the 2018 proxy season, there was considerable speculation as to whether companies would continue to engage their boards on economic relevance and ordinary business exclusion analyses, or if the relative ineffectiveness of the approach (as a basis for exclusion for shareholder proposals) would discourage companies from taking up the board’s time on these reviews of shareholder proposals. Based on our review of the 105 ESG-related no-action requests from the 2019 season, relatively few (18) included the type of board analysis that was introduced by SLB 14I, suggesting that after the initial issuer enthusiasm about the new approach, companies may now be more reluctant to take up the board’s time on these detailed discussions and analyses in light of the limited successes evidenced in the results of last year’s proxy season. Companies may have been further emboldened by the SEC staff’s comment in SLB 14J to the effect that the absence of a discussion of the board’s analysis creates no presumption against exclusion.

Case Study: Board Analysis Referenced in SEC Responses

As mentioned above, there is considerable debate about the benefits and burdens of performing the type of board analysis referenced in SLB 14I and SLB 14J, and we observed that a number of the no-action letters that did include a description of the board process and analysis either did not receive no-action relief on such basis or received relief on other grounds, such as micromanagement or substantial implementation, as discussed below. There were, however, two letters where the SEC staff response specifically referenced the presence or absence of the board’s analysis, and which shed some light on this issue.

Walgreens received a shareholder proposal requesting a report describing the corporate governance changes it has implemented to more effectively monitor and manage financial and reputational risks related to the opioid crisis, including board oversight, formal designation of the issue by the company as a corporate social responsibility issue, and changes in executive compensation arrangements. [3] Walgreens sought to exclude the proposal based on Rule 14a-8(i)(7) both on ordinary business and micromanagement grounds. With respect to ordinary business, Walgreens argued fairly compellingly that the SEC staff had long recognized a distinction between manufacturers and retailers, permitting retailers to exclude proposals relating to products sold by them and manufactured by others, citing letters relating to retail sales of guns and tobacco, among other things. Walgreens also argued that the proposal related to specific products being offered by the chain, amounting to micromanagement. With respect to the question of whether the opioid crisis represented a significant policy issue that transcends ordinary business operations, Walgreens focused on the fact that the substance of the underlying proposal related to the products offered and sold, rather than the question of whether the policy issue itself was significant and sufficiently related to the company’s business, in terms of financial impact and reputational risk, to merit inclusion.

The SEC staff did not concur with Walgreens’ analysis, stating, “We are unable to conclude that this particular proposal is not sufficiently significant to the company’s business operations such that exclusion would be appropriate. The information presented includes neither a board analysis nor other analysis addressing the significance of the particular proposal to the company’s business operations. Specifically, the company discussion does not review the significance of its dispensing (or prior distribution activity) of opioid products.” It appears that in light of the overwhelming attention given to the opioid crisis in the media and among policy makers, and the breadth of the request in terms of impact on the company, the SEC staff was not prepared to make a judgment about significance to the company without the board weighing in.

Reliance Steel & Aluminum Co. was successful in excluding a proposal requesting a report on the company’s policies, contributions and expenditures relating to political contributions under the economic relevance exclusion. [4] Reliance Steel & Aluminum Co. argued that it made no direct political contributions in the last five fiscal years and only its dues payable to a trade association could be characterized as an indirect political contribution, which dues were significantly below the 5% minimum threshold necessary to demonstrate economic relevance. The letter also included a description of the board’s process and analysis, in which the board concluded that the proposal did not present an issue that transcends the company’s ordinary business operations and lacked sufficient nexus to the company, noting the factors the board considered, including that the trade association itself makes no political contributions of any kind. In concurring on the basis of Rule 14a-8(i)(5), the SEC staff made specific reference to the board’s analysis of the issue and cited some of the factors considered by the board, suggesting that as the SEC staff begins to depart from its formerly rigid approach to the economic relevance test, as it foreshadowed in SLB 14I, it intends to emphasize its reliance on the analysis of the company’s board.

Micromanagement as a Basis for Exclusion

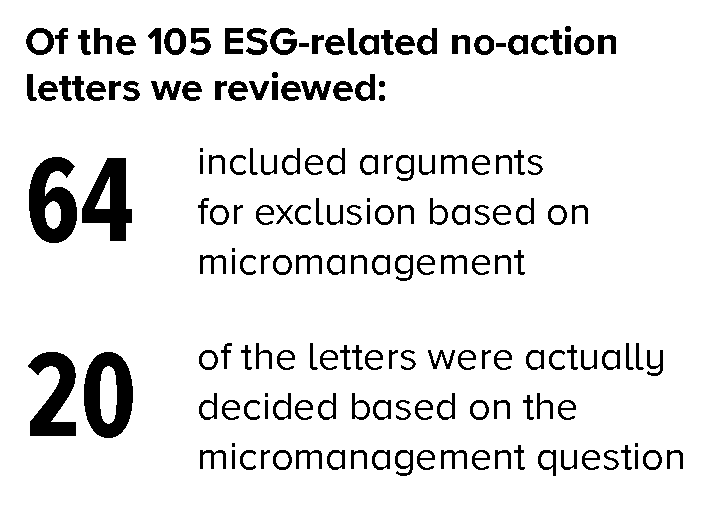

As in 2018, the 2019 proxy season had numerous examples of no-action letters that sought exclusion under Rule 14a-8(i)(7) based on micromanagement. Claims of micromanagement have become more prominent as the SEC staff has become more receptive to such exclusions, even where the underlying issue represents a significant policy issue and would not likely be excluded based on subject matter alone.

SLB 14J included a short discussion of micromanagement, in which the SEC staff clarified that the ordinary business exemption rests on two central considerations—the first relating to the subject matter, and the second, the degree to which the proposal “micromanages” the company by probing too deeply into matters of a complex nature as to which shareholders as a group would not be in a position to make an informed judgment. SLB 14J states clearly that a proposal may be excludable if it micromanages, even if it would not otherwise be excludable based on subject matter. SLB 14J states that a proposal may probe too deeply into matters of a complex nature if it involves intricate detail, or seeks to impose specific timeframes or methods for implementing complex policies. As an example, SLB 14J refers to an Apple shareholder proposal that asked the company to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by the year 2030, which went too far by including a specific timeframe. SLB 14J also confirms that this analysis applies equally to proposals that call for a study or report, so that a proposal requesting a report may be excludable if the substance of the report relates to the imposition or assumption of specific timeframes or methods for implementing complex policies. Given the complexity of the issues covered in many ESG-related shareholder proposals and the fact that they often ask for studies, the micromanagement prong is an important basis for companies to consider in seeking exclusion.

Case Study: Micromanagement in No-Action Requests for ESG-Related ReportsIn the 2019 proxy season, various proponents submitted similar proposals on climate change to a number of energy companies and banks, requesting the boards of those companies to adopt targets, or to include in annual reporting a discussion of targets, or to adopt policies to reduce the carbon footprint of the company’s loan and investment portfolios, in each case, in conformity with the greenhouse gas reduction goals established by the Paris Climate Agreement to keep the increase in global average temperature below two degrees Celsius. [5] In the related no-action requests, the companies argued that the proposal micromanaged the company and was therefore excludable under Rule 14a-8(i)(7). In all cases, the SEC staff concurred, finding that by imposing the overarching requirement of compliance with the Paris Climate Agreement, the proposals were seeking to impose specific methods for implementing complex policies, a task that requires the ongoing judgments of management as overseen by the board.

In contrast, Anadarko Petroleum received a proposal requesting a report describing if and how the company plans to reduce its total contribution to climate change and align its operations and investments with the Paris Agreement’s goal of maintaining global temperatures [(sic)] well below two degrees Celsius. [6] The company convincingly argued that such a report would essentially force the company to adopt a company-wide quantitative and time-bound reporting system measured against the Paris Climate Agreement, but the SEC staff disagreed. While SLB 14J clearly states that a proposal calling for a report may be excludable if the substance of the report relates to the imposition or assumption of specific timeframes or methods for implementing complex policies, the SEC staff may have found a distinction from the letters referenced above based on the inclusion of the “if and how” language of the proposal.

Substantial Implementation as a Basis for Exclusion

Rule 14a-8(i)(10) allows a company to exclude a proposal if it has been substantially implemented. The stated purpose of the exemption is to avoid the possibility of stockholders having to consider matters that have already been favorably acted upon by management. [7] When a company can demonstrate that it has taken action to address each element of a proposal, the SEC staff has generally concurred that the proposal may be excluded based upon “substantial implementation.” The proposal need not be fully implemented in order to justify exclusion. [8] Differences are permitted if the essential objectives of the proposal are satisfied, or where the actions taken by the company “compare favorably” to the actions requested in the proposal. [9] The “substantially implemented” exemption is important in the context of ESG-related shareholder proposals, because often, the subject matter relates to matters that go to the reputation or brand of the company or implicate issues that are otherwise integral to a company’s business and therefore have already been carefully considered by the board and management. As a result, companies may have already taken steps with respect to the issue, such as engaging with shareholders and other stakeholders, publishing reports or other information or developing policies with respect to the issue. Companies should, therefore, review their existing and planned actions with respect to the subject matter of the proposal to see whether they can construct a patchwork of actions that together compare favorably with the actions requested.

Case Study: Shareholder Proposals Seeking New Board Committees to Oversee ESG Matters

A number of shareholder proposals were brought during the 2019 proxy season requesting companies to create board committees to oversee certain ESG-related topics. While several of these were successfully excluded on ordinary business grounds, [10] the outcomes of others were determined on substantially implemented grounds. Apple received a request to establish an international policy committee to oversee policies including human rights, foreign governmental relations and international relations affecting the company’s international business, especially in China. [11] Verizon was asked to establish a public policy and social responsibility committee to oversee its policies and practices that relate to public policy issues that may affect the company’s operations, performance, reputation and stockholder value, including, among other things, human rights, corporate social responsibility and political and lobbying activities and expenditures. [12] ExxonMobil was requested to establish a climate change committee to evaluate its strategic vision and responses to climate change, and better inform board decision making on climate issues, indicating that the charter should explicitly require the committee to engage in formal review and oversight of corporate strategy, above and beyond matters of legal compliance, to assess the company’s responses to climate-related risks and opportunities, including the potential impacts of climate change on business, strategy, financial planning and the environment. [13] In each case, the company concluded it could exclude the proposal under Rule 14a-8(i)(10) on the basis of substantial implementation after describing the existing board committee with oversight responsibility for the referenced subject matter and the extensive disclosures the company makes about oversight and policies on the relevant matters. The SEC staff concurred in the case of the Apple and Verizon requests for no-action relief, but was unable to concur in the case of the ExxonMobil letter.

It is difficult to determine whether the different outcome in ExxonMobil was related to some perceived difference in the analysis in the no-action letter requests (although that is not apparent on the face of the letters). The result in ExxonMobil may also have been based on the proposal’s more specific references to charter requirements in the charter of the proposed committee that perhaps could not be demonstrated to exist in the existing board committee charters, although it would seem a bit overly technical to prevent exclusion simply because the proposal asks for specific charter language. Given the success of similar letters on the basis of the ordinary business exemption, the result suggests that companies faced with new committee proposals should base their exclusion requests on both the ordinary business and substantially implemented exemptions wherever possible.

ESG-Limiting Proposals

One interesting phenomenon in the area of ESG-related shareholder proposals is the emergence of what can only be characterized as “ESG-limiting proposals” by proponents who argue that companies should not be engaging in voluntary efforts to support environmental sustainability or other initiatives.

For example, proposals entitled “Greenwashing Audit” were brought at Duke Energy and Exelon Corporation by the same proponent, in each case, requesting an annual report on actual incurred costs and associated benefits to shareholders, public health and the environment of the company’s voluntary environment-related activities. [14] In both cases, the companies were unsuccessful in excluding the proposals based on vagueness, ordinary business or substantial implementation grounds, despite a detailed discussion of the board’s analysis and, in each case, noting that the proponent is a co-founder of a pro-coal special interest group and runs a website critical of climate change science, which the letters claimed puts the proponent at odds with the views of the majority of the companies’ shareholders.

Interestingly, ExxonMobil was successful in excluding a similar proposal from a different proponent on substantial implementation grounds. [15] The proposal was worded somewhat differently, asking the board to adopt a policy not to undertake any energy savings or sustainability project based solely on alarmist climate change concerns (except where required by law), but that each project should meet financial return on investment metrics. Because of the financial focus of this proposal, as opposed to the more general consideration of the risks and benefits of engaging in sustainability efforts in other proposals, ExxonMobil was able to successfully argue substantial implementation. ExxonMobil supported its substantial implementation argument by referencing specific language in its annual report on Form 10-K, discussing its analysis of the short-term and long-term financial benefits of its projects (including those that contain a potential energy savings or sustainability component), and emphasizing that climate change risk is not just a societal issue but also represents a business opportunity, as customers are seeking solutions to mitigate those risks as well.

What Should Companies Do Now?

As the interest in ESG continues to grow, so will the number of shareholder proposals on ESG-related topics. As mentioned above, ESG proposals are somewhat unique in that they often relate to issues that companies and their boards have already considered in detail, and may have been the subject of public disclosures and of shareholder engagement. In the face of a new proposal on an ESG topic, companies should keep the following practical pointers in mind:

- Inventory previous company actions on the subject matter of the proposal, including whether it has been the subject of prior board consideration, disclosure, shareholder engagement or a shareholder vote. For large and geographically broad companies, consider creating this inventory preemptively, to be ready when a proposal comes in. Consider discussions with the proponent, as a means to educating the proponent about the company’s existing and planned actions with respect to the subject matter of the proposal. Because ESG proposals frequently relate to issues that are already of importance to the company, this kind of engagement can sometimes secure a withdrawal. Try to link each element of the proposal to an existing or planned practice, policy or disclosure of the company so as to support an argument for exclusion.

- Consider discussions with the proponent, as a means to educating the proponent about the

company’s existing and planned actions with respect to the subject matter of the proposal. Because ESG proposals frequently relate to issues that are already of importance to the company, this kind of engagement can sometimes secure a withdrawal. - Try to link each element of the proposal to an existing or planned practice, policy or disclosure of the company so as to support an argument for exclusion.

- If the proposal relates to the company’s ordinary business, consider carefully the nature of the proposal and related precedent no-action letters, then evaluate whether the type of board analysis described in SLB 14I and 14J may be critical in order to obtain exclusion. This will allow an informed balancing of the benefits and burdens of taking the board’s time on the issue. Consider whether the proposal can be characterized as “micromanaging” the company, which is one of the clearest paths to exclusion. Consider requests for exclusion in the broader context of the company’s reputation and brand and how it wishes to communicate about the issue. Consider whether the company would want to be seen as opposing a proposal which its customers and employees would be largely in favor of, although if the company includes such a proposal in its proxy statement, it will typically recommend against the proposal with an accompanying opposition statement.

- Consider whether the proposal can be characterized as “micromanaging” the company, which is one of the clearest paths to exclusion.

- Consider requests for exclusion in the broader context of the company’s reputation and brand and how it wishes to communicate about the issue. Consider whether the company would want to be seen as opposing a proposal which its customers and employees would be largely in favor of, although if the company includes such a proposal in its proxy statement, it will typically recommend against the proposal with an accompanying opposition statement.

Endnotes

1231 no-action letters responded to by the SEC staff from October 1, 2018 through July 31, 2019 were reviewed. 105 of these letters were categorized as relating to ESG matters, excluding what were categorized as “ordinary” corporate governance proposals relating to matters such as board declassification or the right to call special meetings.(go back)

2See Shearman & Sterling LLP, Corporate Governance Survey 2018, “Shareholder Proposals 2018 — Was 14i Really a Game Changer?”(go back)

3Walgreens Boots Alliance, Inc. (November 20, 2018). All citations to no-action letters are references to letters posted on the SEC’s website.(go back)

4Reliance Steel & Aluminum Co. (April 2, 2019).(go back)

5See ExxonMobil Corporation (April 2, 2019), The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. (March 12, 2019), Wells Fargo & Company (March 5, 2019), Devon Energy Corporation (March 4, 2019, reconsideration denied April 1, 2019) and J.B. Hunt Transport Services, Inc. (February 14, 2019).(go back)

6See Anadarko Petroleum Corporation (March 4, 2019).(go back)

7See SEC Release No. 34-12598 (July 7, 1976), interpreting the predecessor rule.(go back)

8See SEC Release No. 34-40018 (May 21, 1998).(go back)

9See, e.g., Apple Inc. (November 19, 2018), Amazon.com, Inc. (March 3, 2016), The Dow Chemical Company (March 18, 2014), Entergy Corporation (February 14, 2014).(go back)

10See, e.g., Amazon.com, Inc. (March 28, 2019), McDonald’s Corporation (March 12, 2019).(go back)

11See Apple Inc. (November 19, 2018).(go back)

12See Verizon Communications Inc. (February 19, 2019).(go back)

13See ExxonMobil Corporation (April 2, 2019).(go back)

14See Duke Energy Corporation (March 12, 2019), Exelon Corporation (March 12, 2019).(go back)

15See ExxonMobil Corporation (April 2, 2019).(go back)

Print

Print