Ethan Klingsberg and Paul Tiger are partners and Elizabeth Bieber is counsel at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer US LLP. This post is based on a Freshfields memorandum by Mr. Klingsberg, Mr. Tiger, Ms. Bieber, and Paul Gray.

A number of commentators have written in recent weeks about a growing trend of issuers of all shapes and sizes adopting shareholder rights plans (“poison pills”). Some even tout the benefits, from a fiduciary duty perspective, of adopting these rights plans now while still a “clear day” (i.e., before a specific hostile threat has emerged)—a thesis popularized by lawyers hawking 10-year pills in the pre-ISS days of the 1980s and 1990s—even though it is now clear that Delaware case law provides more than ample flexibility in the application of the Unocal standard for a well-advised board of a non-controlled company with a single class of common stock to adopt a pill quickly “no matter what the weather.”

These voices are playing off fears and anxieties of boards that arise from the COVID-19 era’s unprecedented volatility, uncertain outlook and depressed market capitalizations. Even though we believe many activists are holding back on announcing new campaigns due to uncertainties around forecasts, there is justifiable concern that deep-pocketed hedge funds, and possibly cash-rich corporations and private equity funds, are accumulating “toe-hold” positions under the radar to position themselves for future threats to companies’ stand-alone strategic plans. Hence, it is no surprise that many directors are asking whether it makes sense to prophylactically adopt a rights plan so that they can effectively cap any holder or group from acquiring beneficial ownership in excess of a specified ceiling—typically 10% to 15% of the company’s outstanding voting power.

However, a review of the data and market considerations underlying the adoption of pills since the market’s COVID-19 roller coaster ride began in the second half of February reveals a more nuanced narrative surrounding recently-adopted pills. This narrative provides useful guidelines for boards deciding how to respond to this new chorus of advice urging them to consider the adoption of this anti-takeover mechanism.

An Analysis of Poison Pills Adopted in the COVID-19 Era

The chart below summarizes the status of poison pill adoptions for the companies comprising five major indices, as of April 12, 2020. Across the board, against the backdrop of the larger effort to limit corporations’ structural devices, poison pills are now largely a device used only on a selective, as-needed basis, as evidenced by the fact that only 91 companies in the Russell 3000 (or 3.0% of the companies in the index) currently have a pill in place, with just 27 of those adopted since February 15, 2020 (representing less than 0.9% of the companies in the index).

| Index | Companies with a Poison Pill in Force as of April 12, 2020 | % of Index |

|---|---|---|

| Russell 1000 (Large to MidCaps) | 16 | 1.6% |

| Russell 2000 (Small Caps) | 75 | 3.8% |

| S&P 500 (Large Caps) | 10 | 2.0% |

| S&P 400 (MidCaps) | 12 | 3.0% |

| S&P 600 (Small Caps) | 24 | 4.0% |

Due to index overlap, the number of pills in place is lower than the total of these rows. Source: Deal Point Data

Given that the COVID-19 crisis hit the US right during the annual meeting cycle for most corporates, to account for any seasonality in the numbers, we also benchmarked against the adoption rate at the same time last year—when the macro-economy and the indices were generally performing well and achieving significant returns. Since this time last year, 40 companies have adopted new, or extended existing, poison pills (13 other companies’ pills have expired or been redeemed in the same time period, for a net increase of 27 year-over-year).

| Index | Companies with a Pill in Force as of April 12, 2020 | Change since February 15, 2020 | Change since April 12, 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Russell 1000 (Large to MidCaps) | 16 | +6 | +2 |

| Russell 2000 (Small Caps) | 75 | +17 | +25 |

| S&P 500 (Large Caps) | 10 | +3 | 0 |

| S&P 400 (MidCaps) | 12 | +5 | +5 |

| S&P 600 (Small Caps) | 24 | +9 | +16 |

Due to index overlap, the number of pills in place is lower than the total of these rows. Source: Deal Point Data

While it is clear that the number of poison pills adopted has increased in recent weeks, the absolute numbers are not statistically significant enough to suggest the market is moving back to wide-spread adoption. Commentary to the contrary ignores the reality that companies adopt poison pills for a number of reasons beyond current market trends or a “good housekeeping” desire to stay safe. In fact, nearly all the recent adoptions can be explained by specific circumstances unique to the companies in question.

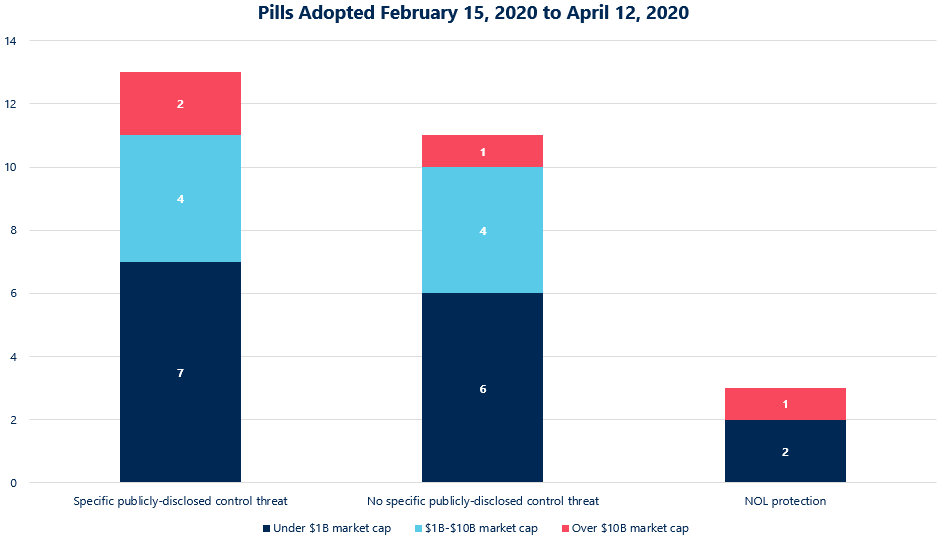

Of the 27 poison pills adopted by the Russell 3000 since February 15, 2020, 13 are attributable to specific publicly-disclosed threats to control. Only five of these 13 cited the pandemic as contributing to the board’s thinking, but the directors at these five companies also had recently filed or amended Schedule 13Ds by an activist or another significant stockholder on their minds.

Three of the 27 companies adopted their pills expressly to protect net operating losses, a legitimate reason for implementation of a rights plan at any time and one that is not driven by a desire to insulate the company from pandemic-related volatility and anxieties.

The remaining 11 companies in the Russell 3000 that have adopted poison pills since mid-February did do so as a result of market volatility and depressed market caps, but their specific circumstances merit attention. Except for one small-cap company re-upping a rights plan to replace its now-rare 10-year pill that was about to expire, each of the relevant companies lost 50% or more of its market capitalization since mid-to-late February—exceeding the decrease in the overall index (which even during the worst trading days of March 2020 never fell below 65% of the mid-February 2020 highs). More importantly, only one of these eleven issuers was in the S&P 500 and six of these 11 issuers had market capitalizations that had dropped to below $1 billion—a significant point since the current reporting threshold for non-passive investments under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act (HSR) is $94 million, meaning that as a company’s market cap approaches $940 million, it would be possible to acquire more than 10% of the company’s voting power without having to file for clearance, which requires notification to the subject company.

Overall, the analysis shows that while there are more companies that have a poison pill in force than as of the same point last year, the companies that should be strongly considering adoption of a poison pill right now, as opposed to those dusting off their “pill on the shelf” to be prepared for quick deployment if and when a threat actually emerges, are currently limited to:

- Companies where a specific, concrete threat to corporate control has emerged either in the form of a takeover proposal, an activist campaign, or an indication, such as disclosure in a Schedule 13D, of an unfriendly accumulation that could amount to a threat to corporate control; or

- Companies with a market cap under or around $1 billion or experiencing volatility that raises reasonable concerns that it might drop to such a range.

Companies with a market cap in the range of $1 billion to $10 billion would do well to be especially attentive whether they are at risk of falling into either of these two categories.

Why this hesitancy—even in the face of the current extraordinary circumstances that are permitting lots of rules to be broken—by the market to adopt pills outright in the spirit that characterized many public company board meetings for at least 15 years following the Delaware Supreme Court’s Moran decision in 1985?

Proxy Advisory Firms Weigh In

One of the significant considerations when determining whether to adopt a poison pill in 2020 is the risk that ISS, Glass Lewis and major institutional investors react negatively to the adoption, and recommend “against” or “withhold” votes in director elections at the next stockholder meeting.

- ISS and Glass Lewis will both recommend, and many institutional investors will exercise, votes against all directors who were on a board during the preceding year that voted in favor of adopting or renewing a pill that resulted in the pill’s having a term of longer than 12 months unless the board obtains shareholder approval of the pill (in addition, the proxy advisory firms will exempt a director from this recommendation if there is disclosure that such director voted against the board’s resolution to adopt or renew).

- ISS and Glass Lewis, as well as many institutional investors, will review pills having a term of no more than 12 months on a case-by-case basis, and the absence of adequate justification may result in withhold or against votes for directors (Glass Lewis typically limits withhold or against votes to governance committee members).

On April 8, 2020, ISS released guidance that reiterated its review of short-term pills (having a term of one year or less) on a case-by-case basis and clarified that a “severe stock price decline as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic” is likely a valid justification for a short-term pill adoption. Glass Lewis issued similar guidance on April 11, 2020. We suspect this justification is significantly improved in the proxy advisory firms’ eyes if 10% of the company’s market cap would be in the range of the $94 million HSR filing threshold. Both proxy advisory firms expect that companies adopting a pill on this basis will include discussion of the rationale, as well as disclosure regarding the length of the term and potential decision to put the plan to a shareholder vote. One important factor is disclosure of outreach to and feedback from stockholders about the rationale for the pill.

It would be a mistake to view these new statements by ISS and Glass Lewis as changes in policies that merit a meaningful change in board deliberations. In particular, it would be imprudent for companies to rush to adopt 12-month pills now that there is a greater chance that ISS and Glass Lewis will accept the rationale as acceptable in its “case-by-case” analysis of pills with a term of up to one year.

In fact, boards should be prudent in deciding when to start the 12-month clock before their pills’ terms (including renewals) trigger the ISS and Glass Lewis policies of automatic withhold/against recommendations. Moreover, there is no assurance that ISS or Glass Lewis will find a board’s case for a 12-month pill compelling notwithstanding the recent policy guidance. For example, the lone S&P 500 company to adopt a pill since mid-February, The Williams Company, had its chairman receive an “against” recommendation from ISS for its upcoming meeting, which cited the ceiling in the issuer’s pill as unjustifiably low (Glass Lewis came out the other way and relied heavily on the issuer’s shareholder engagement around the adoption of the pill).

What Companies Should Be Doing Now

The first line of defense for almost any company is a well-reasoned stand-alone plan, pressure tested by both the board and management. Given the current uncertainty, this may require using different cases and probability weighting, possibly with two or three waves of pandemic contemplated, with different timelines in different geographies. It is important for issuers to continue to work on their internal strategic plans now as that internal preparation by the board will be the underpinnings for the company to message externally its post-pandemic strategic plan. We expect this messaging will need to happen well in advance of when remote working and other pandemic restrictions have ceased to apply. If companies and boards fall behind on this, they risk letting the activists do the work for them and being forced to act in reactive mode, rather than having prepared and communicated proactively.

While we do not recommend reflexive adoption of a poison pill, a well-prepared board should receive periodic briefings on the pros and cons, as well as the underlying mechanics, of a poison pill. In particular:

- A board should be regularly informed about the company’s structural defenses and periodically consider enhancements while balancing those enhancements against the risk that these enhancements will damage the company’s “good governance” profile with investors and proxy advisory firms;

- A company should be sure to have a poison pill “on the shelf” in a form and with terms that are both understood by the board and have been cleared with the company’s transfer agent in advance so that the board can act quickly to adopt it on short notice if circumstances warrant;

- Moreover, the board should be familiar with the relevant Unocal proportionality framework for review of directors’ actions in adopting a new pill or leaving in place an in-force pill under Delaware law (or other applicable law of the state of incorporation) and the views of the proxy advisory firms and the company’s main institutional investors on pills; and

- The board should also be updated about changes in the stockholder base and potential indications of hostile activity, and updated about how volatile market performance may affect the company’s overall defense profile.

These exercises can be effective tools for directors to fulfill their duties to not inadvertently or passively cede control of the company (particularly, without extracting a premium for such control) (as we discuss here).

While it can be difficult during a period of extreme volatility to understand and forecast a company’s future, understanding that these should be priorities for the board even as boards deal with the immediate crisis at hand will be important. Absorbing the impacts, building out a model and business plan and effective communication will likely be one of the distinguishing factors between winners and losers in the coming years.

Print

Print