Jonathan Neilan is Managing Director; Peter Reilly is Senior Director; and Glenn Fitzpatrick is a Consultant at FTI Consulting. This post is based on their FTI Consulting memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here) and Socially Responsible Firms by Alan Ferrell, Hao Liang, and Luc Renneboog (discussed on the Forum here).

Putting the ‘S’ in context

In early 2019, we wrote a paper highlighting that the focus on Environmental, Social & Governance or ‘ESG’ issues in the capital markets had firmly shifted from the margin to the mainstream. This shift was reflected in the scale of capital being invested in ESG oriented investment funds alongside a generally greater societal awareness (and acceptance) of an urgency to step up efforts to address environmental issues and climate change.

As we continued to engage with companies and investors during the course of 2019—and we assessed the corporate reputation challenges being encountered by many companies—it became increasingly clear that factors which fall within the ‘S’ of ESG are as common as (and for some companies more so than) those within ‘E’ and ‘G’ in contributing to business risk and, in turn, causing lasting damage to a company’s reputation.

Factors which fall within the ‘S’—frequently customer or product quality issues, data security, industrial relations or supply-chain issues—commonly impact businesses and ‘destroy value’. This prompted us to reconsider if ‘social’ was the correct word for the ‘S’ in ESG and whether ‘Stakeholder’ might be more appropriate. Indeed, the use of the term ‘social’ may have contributed to a failure to conceptualise the ‘S’ in ESG, leading to an absence of focus and measurement from the market.

The scope of ‘S’ has progressively widened over the past two decades, which reflects the evolving business environment of the 21st century where businesses and markets are increasingly interconnected and interdependent. Over and above human rights; labour issues; workplace health & safety; and product safety and quality, ‘S’ factors now also incorporate the impact of modern supply-chain systems and the adoption of technology across all business sectors.

In looking at examples of ‘S’ practices among businesses, it was also evident that these practices are a barometer for corporate culture. Where companies have a strong and shared culture across the organisation, ‘S’ practices tend to be strong. Where a culture is poor, or considered ‘toxic’, ‘S’ tends to follow the same pattern.

As we entered 2020, the question we had asked ourselves in 2019 took on new meaning. The pace, scale and depth of the COVID-19 crisis is without parallel in our lifetime. In the ten years since the financial crisis, we consistently heard that a crisis of this scale was a ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ event. Unfortunately, this is no longer the case. We are now facing an economic outlook more uncertain than possibly at any time since the Second World War and with an impact that could equal, or exceed, the Great Depression.

In addition, in this environment, ESG cannot be properly considered without reference to the wider sustainability agenda and role of public policy in driving a fundamental change to the relationship between economies, society and the environment. ESG is now clearly mainstream to corporate strategy.

Against that backdrop, factors relating to ‘S’ are now among the most pressing issues for companies globally. The use of the word furlough, with its origins as a military term, and previously largely confined to the airline industry during the boom-bust of their economic cycle, is now commonplace. Some Boards and executives are ‘sharing the pain’ alongside their employees—many of whom have transitioned ‘overnight’ from members of high-performing businesses to effective unemployment. Entire sectors of the economy, and not just the weakest players, are facing a stark and uncertain future. As we look forward, we believe now, more than ever, that a company’s reputation—its ‘licence to operate’—will be a function of how it engages and manages it stakeholders through this crisis; and how it communicates that responsibility—the ‘S’—to its stakeholders in a clear and transparent way.

The environment we now find ourselves in has also affirmed that we would be better served dropping the ‘social’ from ESG and replacing it with the more appropriate ‘S’: ‘Stakeholder’.

Uncertainty prevails

Despite the progressive increase in emphasis on ESG in recent years—by companies, investors and wider society—many market participants have struggled to grasp precisely what role the ‘S’ should play in company frameworks and integration into investment decisions. While companies have made significant progress in disclosure on their environmental impact and governance standards, the same cannot be said of social impact and performance. This is perhaps unsurprising—good governance practice transcends sectors and an organisation’s impact on the environment tends to emanate from measurable and widely accepted criteria. Other factors such as the urgency around climate change and enhanced governance oversight post the 2008 financial crash have also perhaps pushed ‘S’ to the background.

A 2019 Global ESG Survey by BNP Paribas revealed that 46% of investors surveyed (covering 347 institutions) found the ‘S’ to be the most difficult to analyse and embed in investment strategies. According to the report, investors understand the ‘E’ and the ‘G’, but the ‘S’ has, for a variety of reasons, suffered from “middle child predicament”:

“A lack of consensus in the industry surrounding what constitutes the ‘S’ makes it harder to incorporate into investment strategies compared to both the ‘E’ and ‘G’. As such, it often acts as an interaction point between these two elements. The range of issues sitting under the ‘S’ umbrella, along with the qualitative nature of social metrics, further contributes to the difficulty of incorporating the ‘S’ into ESG analysis. A lack of social reporting from companies adds another layer of complexity.”

These sentiments are echoed by the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (‘PRI’), which stated that, despite the increasing prominence of ‘S’ factors, the lack of data and consistency presents challenges:

“The social element of ESG issues can be the most difficult for investors to assess. Unlike environmental and governance issues, which are more easily defined, have an established track record of market data, and are often accompanied by robust regulation, social issues are less tangible, with less mature data to show how they can impact a company’s performance. But issues such as human rights, labour standards and gender equality—and the risks and opportunities they present to investors—are starting to gain prominence.”

A 2017 study by the NYU Stern Centre for Business & Human Rights reviewed reporting and ‘gaps’ relating to the ‘S’ based on frameworks set out by 12 different bodies (including Bloomberg, Dow Jones, FTSE, GRI and SASB). While progress on ESG frameworks and reporting has advanced since that report was issued, the findings of the study are instructive. The report outlined that measurement of ‘S’ usually focused on what was “most convenient” as against what was “most meaningful”; and that ‘S’ measures are often “vague”. Consequently, measuring ‘S’ was unlikely to yield the information needed to identify social leaders among issuers.

A lack of consistency across the various frameworks also resulted in “noisiness” [sic] across ESG ratings—a factor which may contribute to a lack of consistency between rating agency scores. A final observation was that existing measurement and analysis of ‘S’ does not “equip investors to respond to rising demand for socially responsible investing strategies and products.”

In a COVID-19 environment, ‘S’ has been dragged into the spotlight and will now attract significantly greater attention from investors than it has to date. It will also garner significant scrutiny from regulators, Government, customers and employees. Where there was a disparate focus on (and reporting of) ‘S’ in the past, it will now clearly be an element of the corporate story and a prominent pillar of a company’s ESG credentials. It is incumbent on companies to grasp the meaning and implications of a strong ‘S’ and to communicate activity and progress to all stakeholders.

This new emphasis on ‘S’ will also bring more scrutiny on third-party rating agencies, such as FTSERussell, MSCI, ISS ESG, RobecoSAM, Refinitiv, and Sustainalytics and reporting frameworks and standards, such as GRI and SASB (see below). Consistent with the views of the PRI that ‘S’ is the most difficult for investors to assess, rating agencies have been criticised for the lack of correlation between their respective ratings; and, to a lesser extent, errors in gathering comprehensive data.

All of this points to the need for a better understanding of ESG among companies and investors; and of most immediate relevance, what companies should focus on to enhance their ‘S’ credentials.

‘S’ being shaped by stakeholders

The ‘middle child’ label for ‘S’ may have been an accurate description until the first quarter of 2020. ‘S’ has now moved to front-of-mind for investors and is high on the agenda for company stakeholders and society. Federated Hermes, a leading ‘responsible investment firm’ maintains that “If you asked anyone who was in the sustainability or ESG space a year or two years ago, they would tell you that somehow the ‘S’ has not been given much visibility… Covid-19 has changed that substantially, and very, very quickly.”

In the early part of the COVID-19 crisis, a number of companies were immediately in the spotlight for poor ‘S’ practices. In the UK, Frasers Group sought to keep its SportsDirect sports retail outlets open in the face of a Government lockdown of all but essential services. Pub group, JD Wetherspoon, claimed that staff should not be paid after its pubs closed and that workers should seek alternative employment at supermarkets. Broad-based criticism of certain companies was echoed by Klaus Schwab, founder of the World Economic Forum, who said that the coronavirus outbreak also revealed “which companies truly embodied the stakeholder model, and which only paid lip service to it, while fundamentally maintaining a short-term profit orientation.” He pointed to the capital allocation practices of the US airlines (many of whom are now in need of Government support) as an example; highlighting they had “spent 96% of their free cash flow during the past 10 years on buying back shares.”

Scrutiny of companies will rise further where they are in receipt of Government support. A stark message was sent by EU Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager when she outlined: “Support comes with strings attached, including a ban on dividends, bonus payments as well as further measures to limit distortions of competition.” This was recently followed by the UK Government who outlined that companies borrowing more than £50 million through the Government support scheme would be blocked from paying dividends to investors, or cash bonuses and pay rises to senior management, except where previously agreed. Andrew Cuomo, New York governor has gone a step further demanding that any corporate bailouts are repaid in full in the event that employees are not rehired after the crisis. Given the public health dynamic of this crisis, the political pronouncements and bailout conditions appear considerably different to those that followed the financial crisis of 2008. A new form of social contract is being moulded between industry, employees, Government and citizens. This is echoed by ratings agency Fitch who outlined that the “conditionality attached to government bailouts reflects the societal perception that restrictions need to encourage businesses to act for the benefit of a broader set of stakeholders.”

Investors have, in a short time, also clearly articulated the importance of ‘S’ in this new world and what it should mean for companies. Legal & General Investment Management (‘LGIM’), encouraged companies: “not to focus solely on their shareholders but to focus on stakeholder primacy and include all stakeholders, especially their employees, supply-chain relationships, the environment and communities in which they operate.” Schroders echoed this sentiment stating: “in the short term companies need to prioritise their key stakeholders, in particular employees but also customers and suppliers. We believe that by focusing on these drivers of long-term returns the benefits to U.K. investors and the economy will eventually be forthcoming.” Schroders were also more forthright on management ‘sharing the pain’ indicating: “Where companies seek additional capital we would expect their boards to suspend dividends and to reconsider management’s remuneration.” Schroders’ stance chimes with that of Klaus Schwab: a good way to evaluate your commitment to your stakeholders is how you use your capital. Investment in those stakeholders may be a short-term cost, but it will benefit companies in the long-term.

While the focus is now on ‘S’ and the actions companies are taking, pressure will remain on companies’ wider ESG practices. Blackrock, the world’s largest asset manager and a strong proponent of business purpose, long-termism and addressing climate risk has committed to maintain its pressure on companies this AGM season on climate, governance and other ESG issues. While recognising there is merit in maintaining the focus on all elements of ESG, whether coming down ‘hard’ on companies on these issues in the midst of this crisis will be well-received remains to be seen.

Putting the ‘S’ in risk

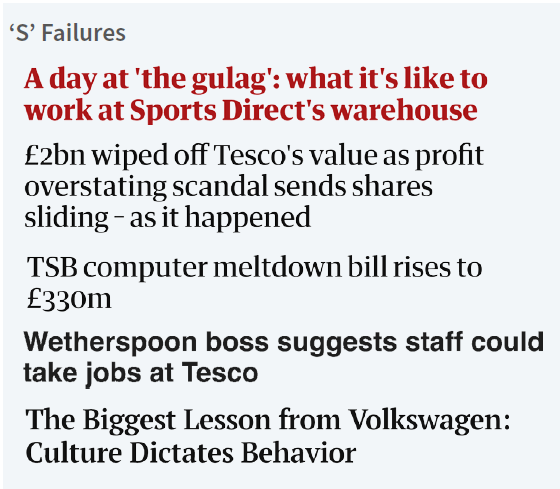

We have consistently maintained that despite difficulties quantifying the ‘S’, stakeholder-centric issues present real risks for companies. While there are a myriad of examples of ‘E’ and ‘G’ failures—environmental disasters and governance failings—many corporate crises are actually failures of ‘S’. A series of headlines included in the box opposite are an indication of ‘S’ failings—which include HR and employment issues; cultural issues; and, data and technology failings—indicating that, even in ‘normal’ circumstances, the ‘S’ requires more focus than it has received up to now. In the current environment, and in a post COVID-19 world, risks associated with the ‘S’ have been magnified.

There are many examples of ‘S’ failures. Even the Volkswagen emissions scandal is arguably an ‘S’ issue more than an environmental one.

Turning to the relevant question as to what ‘S’ represents, despite the many differing views, the factors laid out by the various rating agencies do coalesce around a few core ideas that essentially amount to what can be framed as stakeholder welfare. Those who are familiar with the UK Corporate Governance Code, largely seen as the global gold standard of corporate governance guidance, will know that incorporating the interests of wider stakeholders into a company culture was set out by the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) within their 2018 update:

“Companies do not exist in isolation. Successful and sustainable businesses underpin our economy and society by providing employment and creating prosperity. To succeed in the long-term, directors and the companies they lead need to build and maintain successful relationships with a wide range of stakeholders. These relationships will be successful and enduring if they are based on respect, trust and mutual benefit. Accordingly, a company’s culture should promote integrity and openness, value diversity and be responsive to the views of shareholders and wider stakeholders.”

Ultimately, the question of how a company’s key stakeholders have fared as a result of their business operations is at the core of measuring ‘S’. Companies will have, for a long time, recognised the importance of key stakeholders—suppliers, customers, employees and partners. However, now it is not simply the practice of engaging with those stakeholders that is relevant—but proof that their views have been considered in Board decision-making. This too was a feature of the revised 2018 UK Corporate Governance Code when the FRC proposed a structure to better facilitate the ‘voice’ of the workforce at Board level, a practice that is prevalent in certain other European jurisdictions.

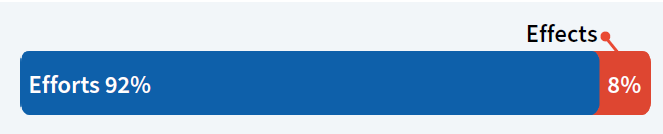

Difficulty in measuring ‘S’ was also outlined in the NYU Stern analysis. In reviewing over 1,750 social metrics from 12 different rating frameworks, they determined that only 8% of those ‘S’ indicators evaluated the effects of company ‘S’ practices; the significant majority (i.e. 92%) measured company efforts and activities. This means that, historically, ratings agencies (and, in turn, investors) have looked more at policies and commitments rather than their impact. In some respects, this is the financial equivalent of assessing a company’s R&D programme by looking at the scale and target of R&D investment without any evaluation of the effectiveness or outcome of that investment.

A 2017 NYU Stern study determined that only 8% of the over 1,750 ‘S’ indicators reviewed,

actually evaluated the effects of company ‘S’ practices; 92% measured company efforts and

activities.

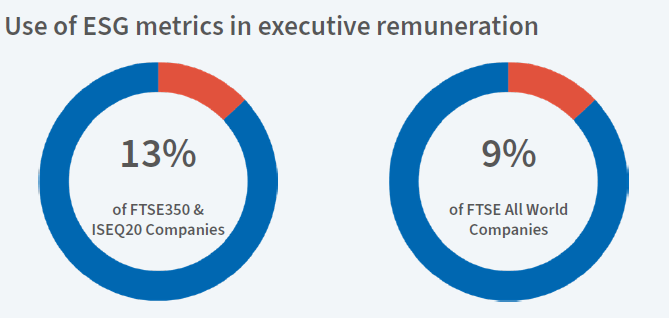

As ESG rating agencies and investors enhance their analysis of the ‘S’ in the period ahead, it will heighten the need for companies to increase disclosure on the outcome/ impact of their initiatives as against solely the ‘in principle’ commitment. As companies consider their ‘S’ credentials—and their ESG profile generally—it will also begin to permeate other elements of business practice in a more meaningful way—including executive remuneration. Our own 2019 research indicates that just 13% of FTSE350 and ISEQ20 companies use ESG oriented measures in executive incentive plans (though the number is higher if you include customer satisfaction measures). On a wider scale, a 2020 study by Sustainalytics indicates that only 9% of FTSE All World companies link executive pay to ESG criteria “most of which address occupational health and safety risks in the materials, energy and utilities sectors.” There are arguments that non-financial or ESG targets can be “soft” but if appropriately designed—specifically “tailored, specific and measurable”—they can “reinforce strategy”.

What the ESG ratings agencies think

In reviewing the ‘S’ criteria set out by all of the leading ESG rating agencies, we have distilled them into five different topics and summarised the issues for companies to consider. This framework provides a basis to consider the practice and disclosure on factors which may positively impact the perception of a company’s ‘S’. These factors will affect companies in different ways and can interact with Board and management’s fundamental understanding of what is important to their companies.

One area that deserves a specific mention is data security and IT integrity. While the prominence of these issues as relevant ‘S’ factors might, at first, seem to be less relevant in a COVID-19 environment, it is undeniable that in the modern world, they present material business risk for companies. They require a significant duty of care. All companies have to assiduously protect the data they hold on their employees and customers; and, also ensure they can transact safely and securely online.

Data security—or lack thereof—has the potential to impact every company and will grow in importance as more business is conducted in the virtual world.

1. Workforce, Engagement and Training

Matters relating to staff appear in various forms across all ratings agency ‘S’ criteria. The extent to which employees, through either their union representatives, a worker director, works council or otherwise, express a voice or have a seat at the table is assessed by multiple criteria.

We see common themes across rating and reporting frameworks such as ‘Labour Relations’ (MSCI), ‘Employee Engagement’ (SASB) and the presence of a ‘Collective Bargaining Agreement’ (Sustainalytics). As outlined, the 2018 iteration of the UK Code includes a new provision on workforce engagement. While some have been slow to take steps to address this provision, there is now a heightened need for meaningful workforce engagement, which will subsequently become a need to demonstrate that it has occurred. This also points to the importance of the Nomination Committee on a Board—whose role could potentially be expanded to incorporate wider HR and employee issues; and ensure that workforce issues are considered at Board level in a more meaningful way.

A related ‘S’ metric is the existence of appropriate procedures and processes covering areas such as equality, diversity & inclusion, disciplinary issues and health & safety. S&P Global, the global credit rating agency, which acquired the ESG ratings business of RobecoSAM in late 2019, has committed to monitoring “how the indirect consequences of safety management and community engagement in this time of duress, for instance, can affect credit quality over a longer time horizon than we currently anticipate for the pandemic and its immediate aftermath.” This highlights that an ESG rating is now likely to have financial ‘consequences’ for a business. Moody’s, another credit rating agency, which also acquired a stake in ESG rating agency Vigeo Eiris in 2019, recently stated “We expect ESG considerations to be of growing importance in our assessment of issuer credit quality.”

And, in what was perhaps a prescient comment prior to this current crisis, J.P. Morgan Chase co-President Daniel Pinto said “Either you are socially and environmentally responsible or you are not, I think that this is the world we are heading towards. It’s possible that some companies will really struggle to finance themselves, their cost of capital will go to the sky and they may not exist going forward.”

Another workforce factor, ‘Human Capital Development’ (MSCI and S&P/ RobecoSAM) captures a range of other aspects of the employer-employee relationship, such as: staff turnover rate, talent attraction and retention, learning and education, productivity levels and the existence on long-term incentives. S&P/ RobecoSAM scores companies on the ‘trend of Employee Engagement’ which is a useful way to conceptualise each of the factors. Some companies will be in a position to use this crisis period to make significant strides with education and upskilling initiatives. Others may be surprised to learn that ESG rating agencies already view the existence and quality of such initiatives when evaluating companies, and have consistently been matters to be considered under the ‘S’. A demonstration of a commitment to lifelong learning and employee development could represent an opportunity for companies who already have such frameworks in place, as investors seek assurance about capabilities and productivity.

2. Customers

Customers regularly appear across ESG ratings agency criteria. Under its ‘Social Capital’ heading, SASB scores companies on both ‘Customer Privacy’ and ‘Customer Welfare’. Sustainalytics also has a ‘Customer Incidents’ measure, whereas it could be argued that MCSI’s social criteria scores companies on all three of those through its ‘Product Liability’ lens, which marks companies on ‘Product Quality & Safety’, and ‘Privacy & Security’. In trying to meet the disclosure requirements for this data, the use of Net Promoter Scores (NPS) by businesses are a useful tool to measure customer satisfaction and a read-through for other related customer factors. They are increasingly used in executive remuneration structures (as a non-financial measure) and will be increasingly important for businesses in a post-COVID world.

But customer factors under ‘S’ go into greater depth. SASB included factors such as ‘Access & Affordability’; ‘Product Quality & Safety’ and ‘Selling Practices & Product Labelling’. These factors may become more acute for companies in the healthcare sector for example as we try to address the healthcare needs of wider and more vulnerable population in future. The recent decision by Gilead Sciences to licence its Remdesivir drug to five generic drugmakers to serve largely low-income countries on a “royalty-free” basis—until the WHO has declared an end to the pandemic or until another medicine or vaccine is approved—is evidence of a business recognising the importance the ‘S’ and its wider role in society.

Supermarket retailers and online retailers are also working to protect and support customers in this environment. Supermarkets have implemented significant new health and safety protocols for customers in-store while some of the online retail giants have taken action to stop price-gouging on their platforms. A deteriorating customer experience will not be tolerated even during these unparalleled times.

3. Community and Society

The extent of a company’s community engagement is also captured by a range of existing social criteria. MSCI’s ‘Stakeholder Opposition’ indicator places companies directly within their immediate surroundings, and within a global community, along with ‘Society & Community Incidents’ (Sustainalytics). Vigeo Eiris look for a more active angle, using ‘Community Involvement’ as a determinant. This is perhaps given less emphasis by SASB, who combine this aspect with a broader look at a company’s human rights record, using a ‘Human Rights & Community Relations’ metric. Pre-COVID-19, this may have implied predominantly focusing on the local but the concept that we are all global citizens has perhaps never been felt as much by all.

4. Data and IT Security

Data and IT security issues are never usually front-of-mind when considering the ‘S’. They are, however, an issue which potentially affects every business in the world. ESG rating agencies all include a range of measures on data and IT security. MSCI breaks down its analysis of ‘Product Liability’ into a range of risk factors including where a business has ‘Exposure to Business Prone to Data breaches or Handles High Volumes of Customer Data’; and ‘Geographic Exposure to Privacy Regulations’. SASB also includes ‘Data Security’ under its ‘Social Capital’ heading.

Investors and ESG ratings agencies are sure to look for assurances that Boards have a firm grasp and understanding of the increased dependency on information and communications technology, systems, and networks. Their security and reliability must (in as much as anything can) be guaranteed. Despite this, the number of Boards with IT capability and cyber security knowledge appears to be relatively low. A 2017 review in Harvard Business Review cited that “most board members have expertise in other forms of risk, and not in how to protect corporate assets from nation-state attackers and highly organized cyber adversaries.” And this stark reality is compounded by the changing nature of business as outlined by Warren Buffet in late 2018 when he stated that cyber risk “is uncharted territory and it’s going to get worse, not better”…adding it is “a very material risk that didn’t exist 10 to 15 years ago, and will get more intense as time goes on.”

In the current environment, concerns around GDPR are also likely to intensify and these may be more difficult for firms to address where key people have been furloughed or must work remotely. This signals again why Boards need to ensure that this is not overlooked. The introduction of GDPR laws by the EU and indeed similar frameworks such as the SEC’s Statement and Guidance on Public Company Cybersecurity Disclosures, had already altered company obligations and increased the scrutiny on the world of data. A fundamental shift in the online/ offline balance of work will inevitably lead to behavioural changes. This anchors data and security issues even more firmly in the ‘S’.

5. Human Rights

While the ‘S’ grows in prominence due to increasing evidence of its potential to significantly impact business performance and reputation, human rights is an area that has traditionally been a material focus for ESG investors and disclosures. In an increasingly globalised world, companies often operate in jurisdictions with varying degrees of protection for employees, communities and consumers. Companies in all sectors with all types of operations should have clear policies on respecting human rights; however, for those with complex supply-chains, oversight is simultaneously important and challenging. At a bare minimum, companies should set out their commitment and adherence to the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights and International Labour Organisation, as well as conventions on child labour, forced labour and modern slavery. Simply noting these policies are part of company frameworks is insufficient though and should be supplemented by consistent due diligence throughout a company’s operations, supply-chain and contractors. The Corporate Human Rights Benchmark (CHRB) details areas of focus for four industries—Agricultural Products, Apparel, Extractives and ICT Manufacturing—based on their high human rights risks, the extent of previous work on the issue, and global economic significance. For many other businesses, transgressing human rights probably seems a very remote possibility; however, through material sourcing, purchasing practices and an increasingly global supply-chain, these risks are more pronounced than many understand. Any evidence of complicity in abuses in this area have lasting effects on a company’s brand and reputation, and may also lead to litigation costs.

Summary

In advising companies on protecting and enhancing corporate reputation—through good and bad times—our guiding principle is to ‘do the right thing’. Simple as it sounds, it is reflected in the adage that ‘good PR starts with good behaviour’. This guiding principle also translates to building your ‘S’ credentials. While the various ESG criteria of the reporting frameworks and ratings agencies are a useful guide, our consistent approach in advising companies is for them to take the steps they believe are genuinely in the best interest of the company and its wider stakeholders. Not every decision will meet the expectations of every stakeholder; but it’s a good place to start.

As the wider sustainability agenda also drives more rapid and fundamental change in global markets and technology innovation, properly considering the pressure from public policy and evolving legal requirements, as well as the needs of key stakeholders, is key to understanding what is (and will be seen as) ‘good behaviour’.

As the focus on the ‘S’ grows, companies will need to shift from a reactive to a proactive position. While governance and environmental data is readily available for most companies, the same is not true of the ‘S’. The leeway companies have been afforded on the ‘S’ in the past is unlikely to continue; and, expectations of (and measurement by) rating agencies and investors will continue to increase.

In light of the economic shocks and social upheaval across the globe, demands from stakeholders—most pressingly investors and Governments—will reach a crescendo over the coming six months. As the sole arbiter of much of the information needed to value the ‘S’ in ESG, companies have an opportunity to demonstrate a willingness to shift levels of transparency before they are forced to do so. Companies understandably tend to highlight the efforts they make, often through their corporate social responsibility or communications departments, rather than the higher-cost, higher-risk analysis of the effectiveness of those efforts. Fundamentally, hastened by the emergence of a global pandemic, the world recognises the significance of the risk that failure to address stakeholder interests and expectations represents to business. That shift can be identified as demand for evidence of positive outcomes as opposed to simply efforts or policies.

As we noted in our 2019 Paper, ESG will never replace financial performance as the primary driver of company valuations. Increasingly, however, it is proving to drive the cost of capital down for companies while playing a hugely important role in companies’ risk management frameworks. Most immediately, companies should get a firm handle on how comprehensive their policies, procedures and data are in the five areas listed through a candid audit, as well as other factors material to their businesses’ long-term success. However, this is just a first step and companies must build a narrative and strategy around disclosure for all future annual reports and, where appropriate, market communications. Investors of all sizes are increasingly driving this factor home to Boards and management. In just one week at the end of April, human capital management proposals from As You Sow, a non-for-profit foundation, received 61% and 79% support at two S&P 500 companies, Fastenal and Genuine Parts, respectively. The two companies must now prepare reports on diversity and inclusion, and describe the company’s policies, performance, and improvement targets related to material human capital risks and opportunities as designed by a small shareholder—as opposed to crafting an approach and associated disclosure themselves.

What has become clear over the past three months is that a host of stakeholders, including many investors, will expect a sea-change in their access to information and company practices. While there is no requirement to be the first mover on this, those that are laggards will face avoidable challenges and a rising threat to their ‘licence to operate’.

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print

One Comment

Maybe the “S” should stand for SURVIVE.