Bhakti Mirchandani is Managing Director and Victoria Tellez is a research associate at FCLTGlobal. This post is based on their FCLTGlobal memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Agency Problems of Institutional Investors by Lucian Bebchuk, Alma Cohen, and Scott Hirst (discussed on the Forum here) and The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, and Wei Jiang (discussed on the Forum here).

Executive Summary

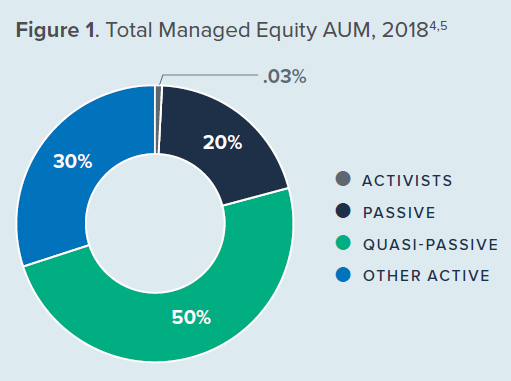

The prevailing wisdom is that activist investors can drive corporate short-term behavior themselves. The prevailing wisdom is wrong. At just 0.3% of total global equity assets under management (AUM) in 2018, activists depend on the support of long-term investors for their influence.

Without clarity on long-term shareholders’ views, companies perceive short-term pressure coming from their investors, and assume the activists speak for the entirety of the shareholder register. Having a strong investor/corporate dialogue well before an activist campaign arises is the way to encourage companies to proactively improve the drivers of long-term value creation—such as bolstering their governance, honing strategies for growth, and engaging with long-term investors. Strong long-term performance is the best way to limit opportunity for an activist campaign. Indeed, rather than being a spectator, long-term investors have a significant role to play alongside companies to counteract short-term activist behaviors. It is well within the power of these long-term investors to either amplify or dampen the short-term impact of activism, serving as essential players of the activism ‘game.’

- Despite their relatively small AUM, activists are an important and growing influence on companies’ short- or long-term behavior globally. Activists have different goals, time horizons, risk profiles, and levels of engagement than most long-term shareholders. These differences can unduly compress corporate time horizons, at times to the detriment of long-term value creation.

- Many activists choose to emphasize the short term at the expense of the long term, perhaps as a result of their event-driven orientation and comparatively higher discount rates. Activists run the gamut from long-term-oriented to short-term-oriented and employ a range of tactics. Research on whether activists create long-term value is mixed, and comparisons are unreliable, given the widespread prevalence of activism in the US market. It is clearer that activist hedge funds discount future cash flows more than other shareholders, favoring corporate strategies that generate near-term results. Given that short-term and long-term shareholders can have very different objectives, it is critical that long-term investors carefully consider their support of activist investors.

- Investors and companies can mitigate the short-term impact of activism by preparing for and responding to activist campaigns in ways that emphasize long-term value. Asset owners could evaluate whether to invest in activist funds and, if so, only under terms that encourage longer-term behavior. Asset managers and asset owners have the opportunity to decide whether and under what conditions to vote with activists, lend their shares to activists, engage with activists, and engage with companies that activists target. Companies can gauge whether improvements in the key drivers of long-term value, such as bolstering their governance, honing strategies for growth, and engaging with long-term investors, would preempt an activist campaign.

In the activist game, long-term investors often determine the final score.

Making the Call: The Role of Long-term Institutional Investors in Activism

Activists are a commonly cited driver of corporate short-term behavior, yet they generally don’t own enough shares to effect change alone. At 0.3% of managed equities, activists need the support of long-term asset owners and asset managers for their campaigns to succeed. For companies, bolstering their governance, honing strategies for growth, and engaging with long-term investors can lay the groundwork to withstand activist attacks. With the right approach, it is well within the power of long-term investors to mitigate the short-term impact of activism.

Driving Short-term Behavior?

Activism—when an individual or group purchases a meaningful portion of a public company’s shares and/or tries to obtain seats on the company’s board to effect significant change within the company—is a key influence on corporate behavior. Activists are typically driven by perceived weak corporate governance or management or by a strategic difference of opinion. In rare instances, they are even invited in by significant investors frustrated with a company’s performance via a “request for activism” (RFA). Activists can take a variety of approaches— negotiations with management, shareholder resolutions, and proxy battles—and exercise them alone or in combination and with varying degrees of aggression and success. According to McKinsey & Co. research, just 24.9% of activist proxy battles that went to a vote resulted in an activist win6—defined as a campaign where management (independently or through shareholder vote) met all activist demands. For companies earning >$1 billion in annual revenue this number was 26.2%.

Activists differ from most long-term shareholders in a number of meaningful ways.

Goals: Activists often seek to change both governance and strategy at target companies, rather than focusing on analyzing companies and determining whether to buy or sell shares based on the strategy management has already set out. This leads to different levels and types of engagement.

Defining Activism

Activist hedge funds (“activists”) typically use an equity stake in a company to put pressure on its management team to effect a significant change. Activists are commonly driven by a perceived opportunity to improve corporate governance or management or by a strategic difference of opinion; today they are occasionally also driven by environmental and social issues. While the terms “activist” and “activism” can be more broadly applied, for the purposes of this research we use these terms in reference only to engagements or campaigns that are primarily event-driven and financially motivated.

Portfolio concentration: Activists have more concentrated portfolios than most investors, creating different risk profiles and driving different behaviors as a result.

Orientation: Activists tend to be deal-driven, often looking to create near-term catalysts for a change in control.

Fee structures: Activists have a higher share of incentive pay and similarly higher discount rates than other asset managers. This structure incentivizes greater risk-taking and a shorter-term mindset among activist hedge funds. That short-term mindset inspires activists to pressure management teams to deliver results more quickly—arguably compressing corporate time horizons and making optimal long-term returns more elusive.

All of these differences affect corporate behavior in response to or in anticipation of an activist campaign.

Activism is Growing and Affecting Traditional Asset Management

Activism is growing, spreading internationally, and impacting traditional asset management. Worldwide, activist engagement, as well as the use of activist-style tactics by traditional asset managers, is steadily increasing. In 2019, for the first time, Japan was the most-targeted non-US jurisdiction, with 19 campaigns and $4.5B in capital deployed (both numbers acquired from local records).

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Investors Engaging in Activism | 109 | 131 +20% |

147 +12% |

| First-time Activist Investors | 23 | 40 +74% |

43 +8% |

| Companies Targeted by Activists | 188 | 226 +20% |

187 -17% |

| Board Seats Won by Activists | 103 | 161 +56% |

122 -24% |

Despite their relatively small size, activists have an outsized impact on corporate executives and boards. To illustrate, from 2010 to 2015, half of the S&P 500 had an activist fund on its share register, and one in seven companies had been on the receiving end of an activist campaign. In addition, 21% of the S&P 500 was approached publicly by an activist shareholder in 2016, versus a record 45%, which were targeted by activists just two years later, in 2018. With activist engagement numbers that high, it’s not surprising that investor relations professionals most commonly identified activism as one of the top two most impactful challenges (along with environmental, social, and governance issues) facing their profession 2019.

Activist Tactics

Activists run the gamut from long-term-oriented to short-term-oriented and employ a range of behaviors from constructive to questionable.

Constructive

- Share new ideas and analysis with company management and shareholders privately

- Provide institutional investors with governance options they can respond to

- Encourage effective monitoring of strategy or boards

Questionable

- Public statements of alternative strategies

- Resorting to resource-intensive proxy battles

- Requesting reimbursement of legal expenses or other cash payments

- Collecting or threatening to release information about management or the board

- Personal attacks on management or board members or their families

- Net short debt activism

Thoughtful Regulators are Taking Action to Curb Excessive Short-Term Activism

Activists have drawn the attention of global leaders, inspiring French and Japanese authorities to take regulatory action.

In April 2020, French regulators came out strongly against short-term activist behaviors, yet also emphasized that certain types of activism can be good for the market and target companies. “Shareholder involvement in the corporate life of an issuer is necessary for its satisfactory functioning. It has accordingly been encouraged by the regulator. The challenge raised by activist practices is not how to prevent activism, but how to control its excesses.”

Similarly, in November 2019, Japanese authorities passed a bill that requires foreign investors to notify authorities before their holdings in potentially sensitive sectors reach one percent (lowering the notification threshold from the prior ten percent level). The law brings Japanese regulation into alignment with the US Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act and was partially in response to increasing activist engagement in the country.

Adding Long-term Value or Prioritizing the Short Term?

It is widely acknowledged that activists can encourage long-term value creation through detailed research and analysis, new ideas, and discipline. When activists engage with an undermanaged company, there can be an opportunity to add value for both short- and long-term shareholders. However, evidence on whether and how often activists indeed create value is thin. First, practitioner evidence is inconclusive. McKinsey finds that the median activist campaign for large companies reverses a downward trajectory in target-company performance and generates excess shareholder returns for at least three years. By contrast, a Lazard study found companies targeted by activists underperformed their benchmark indices in Europe.

Second, academic evidence on whether activism creates long-term value is inconclusive, due to the prevalence of activism, especially in the US market. The studies that find a positive long-term impact of activism for the typical shareholder are equally weighted, and the positive impact of activism is based on the smallest 20% of firms by market value— so small, in fact, that this cohort had an average market value of just $22 million. The larger 80% of firms experience insignificant negative long-term returns. One notable exception took activist target company size into account and found that activist hedge funds do not destroy long-term value, defined as a five-year return on assets following the activist attack. Comparisons are also problematic. Since activism has been prevalent in the US markets—the focus of the majority of activist studies—for decades, and activist campaigns on peers also shape company behavior, it is difficult to compile a control group of firms that are not affected by activism.

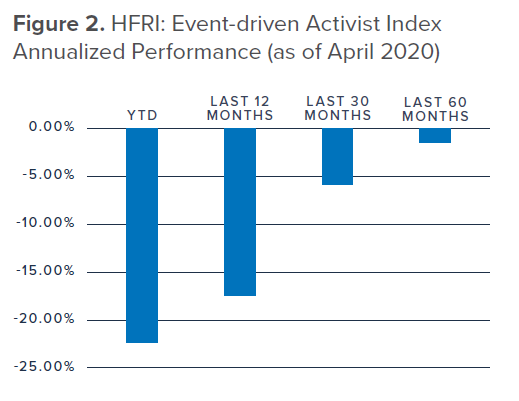

Finally, taken as a group, the performance of activist hedge funds themselves has been poor. As demonstrated by the HFRI® Event-Driven Activist Index, activist funds have underperformed on a one-, three-, and five-year basis in terms of annualized performance.

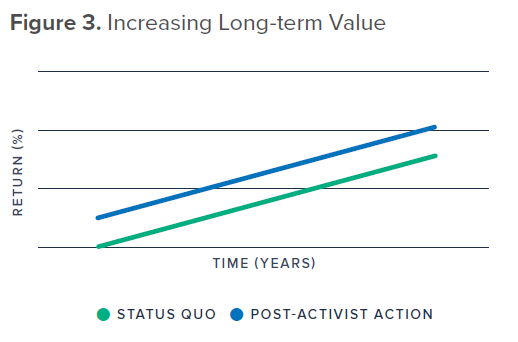

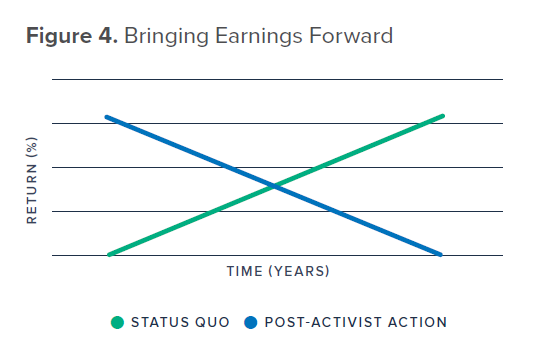

Notably, we could not find academic evidence of long-term value creation by activists. By contrast, academic research more clearly demonstrates that activist hedge funds almost exclusively prefer shorter-term returns. Activist hedge funds represent an extreme among shareholders in discounting future cash flows more heavily than other shareholders, due to the greater uncertainty of valuing long-term outcomes within their shorter time horizons. This, in turn, may shorten corporate time horizons, thereby triggering corporate executives and boards to prioritize actions that yield more immediate financial returns at the expense of greater long-term value creation. Indeed, activists could increase long-term value in some situations, but often opt to “bring earnings forward” instead.

These findings emphasize the roles that different shareholders play in balancing a firm’s short- and long-term financial and non-financial priorities. In fact, it is difficult, if not impossible, for a corporate management team to please both short-term and long-term shareholders in its strategic decision-making, making it even more critical for long-term investors to make their own interests clear and carefully consider under what conditions to engage with, invest with, and support activists.

Tools to Mitigate the Short-term Impact of Activism

Asset owners determine whether to invest in activist funds and, if so, under what terms. Asset owners and asset managers must decide whether and under what conditions to vote with activists, lend their shares to activists, engage with activists, and engage with companies that activists target. Shareholder support for activist campaigns is often based on the relative reputations for long-term value creation of the activist and the company engaging with the activist. Activists have built their reputations for building long-term value through prior deals and actions. Long-term investors who vote with activists, and asset owners who invest with activists, legitimize the behaviors of those activists and expose themselves to potential reputational risk by such association.

But it isn’t just reputation that is on the line with these decisions. As demonstrated, the evidence for activists adding long-term value is thin. For investors with particularly long time horizons, activist tactics that pull forward earnings—cannibalizing future growth opportunities or starving them of growth capital in favor of juicing near-term earnings—can have a negative impact on long-term returns. Encouraging such behavior is not aligned with the stewardship and fiduciary goals of most long-term investors.

With the right tools, long-term asset managers and asset owners can provide an important counterbalance to activist pressure to shorten corporate time horizons. Since activists rely on asset owners as their source of funds and on other significant shareholders and asset managers for support, long-term owners and managers have a significant role to play when it comes to mitigating the short-term impact of activism. In the pages that follow, we lay out a framework for use in evaluating these decisions and taking action to counterbalance questionable activist tactics.

Considerations for Corporations

The proliferation of activist engagement over the past two decades has inspired many companies to anticipate activist attacks and plan for such contingencies. Companies considering such preparation can gauge whether improvements in the key drivers of long-term value, such as bolstering their governance, honing strategies for growth, and engaging with long-term investors, would improve their long-term performance and forestall an activist campaign.

Conclusion

Activists are an important and growing influence in capital markets worldwide. With different levels of engagement, time horizons, risk profiles, and goals than most long-term shareholders, activist investors often have motivations that are not aligned with the interests of long-term investors. Activists can add long-term value to undermanaged target companies, but many emphasize the short term at the expense of the long term. However, while activists are often described as driving corporate short-term behavior, they depend on long-term investors for their influence.

These findings emphasize the function that different shareholders have in balancing a firm’s short- and long-term financial and non-financial priorities. With the right tools, long-term asset managers and asset owners can counterbalance activist short-term pressure—and companies can proactively improve the drivers of long-term value creation to remove underperformance as the incentive for an activist campaign. More broadly, asset owners, asset managers, and corporations can mitigate the short-term impact of activism by engaging in a constructive ongoing dialogue in ways that emphasize long-term value.

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print