Michael Ewens is Professor of Finance and Entrepreneurship at the California Institute of Technology; Ramana Nanda is Sarofim-Rock Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School; and Christopher Stanton is Marvin Bower Associate Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School. This post is based on their recent paper. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes the book Pay without Performance: The Unfulfilled Promise of Executive Compensation, by Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried and Executive Compensation as an Agency Problem by Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried.

Venture capital investors have developed an extensive set of tools to help address financing frictions for startups stemming from adverse selection and moral hazard. These include a focus on rigorous due diligence, complex security design, staged financing and active investment through extensive control rights, such as board seats. However, despite the importance of VC-backed firms and the wealth of information on these many solutions, little is known about the compensation contracts of founder-CEOs in private, venture capital-backed firms.

This gap is important for two reasons. First, exploring when professionalized CEO contracts emerge in the firm’s lifecycle reveals important features of how VCs implement dynamic contracts. Theory suggests that, at least initially, venture capital contracts have to leave founders bearing substantial non-diversifiable risk at the birth of firms in order to screen entrepreneurs. However, the value of screening is likely to fall as firm performance becomes publicly observed, suggesting that incentive alignment should increasingly dominate screening motives as firms mature.

Second, since entrepreneurs are intricately tied to the ideas they commercialize at the birth of new ventures, the compensation contract they face, and the risk they bear, are important for determining which ideas are brought to market. A critical component of the risk borne by entrepreneurs is the amount of time between starting a firm and an entrepreneur’s ability to access a liquid source of cash, either through salary, bonus compensation, or realized capital gains. The longer the delay until founders can access liquid cash, the greater is their “burden of non-diversifiable risk.”

We first explore whether founder-CEO compensation in VC-backed firms responds to a dynamic information environment, such as achieving key milestones. To do so, we use individual-level data from Advanced HR, a leading provider of executive compensation data for VC-backed startups, to study both the level and evolution of CEO compensation. We link, at the individual executive-level, their salary, bonus, and equity holdings to firm-level information on financing, revenue, headcount, and product milestones. We also observe whether the executive is a founder or not, and we have rich covariates on the startup firm’s industry, location, and age.

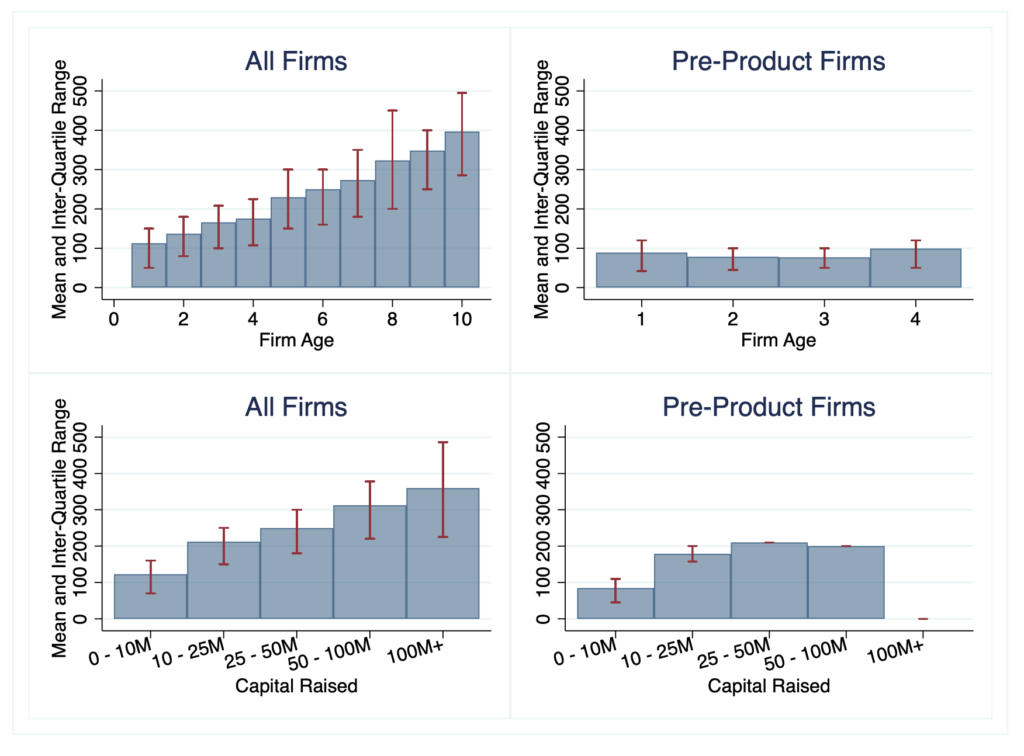

Figure 1: Founder-CEO Cash Compensation by Firm Age and Capital Raised

The figure displays founder-CEO cash compensation by firm age and capital raised. The left panels include all firms and the right panels restrict the sample to firms that are still in the product definition or ideation phase.

Founder cash compensation is indeed minimal at the birth of ventures. However, development of a tangible, marketable product stands out as a critical milestone that drives an apparent transition in the compensation contract between investors and founder-CEOs to one that is more standard in mature firms. Figure 1 shows this pattern clearly. The top right panel of conditions on “Pre-Product” firms that have no revenue and have not yet achieved viable product definition. This panel suggests that the overall increase in compensation with firm age stems from the increasing number of surviving firms that have achieved product market milestones and the death of firms that fail to achieve product traction. The bottom panels plot similar figures, but instead of focusing on age, the x-axis is capital raised. These figures suggest that having a viable product is a significant inflection point for CEO compensation. Achieving product milestones thus reduces the need to screen entrepreneurs with low compensation, enabling founders to begin earning market salaries.

Having documented this milestone as a key inflection point in the compensation contracts of CEOs, we turn next to studying how quickly product market fit is achieved, as a means to quantify the attractiveness of the entrepreneurial career path. Most entrepreneurs transition to entrepreneurship from wage employment. In addition to being riskier than wage employment, entrepreneurship also entails starting off with minimal liquid cash compensation. Individuals’ pre-entrepreneurship wages, as well as their net wealth, therefore play an important role in determining their opportunity costs and the degree to which they can smooth consumption. This in turn impacts whether they find it financially attractive to pursue VC-backed entrepreneurship.

However, because cash compensation increases substantially following product market fit, it is not just the initial level of cash compensation, but rather the speed with which milestones are achieved (and hence uncertainty resolved) that determines the extent of risk facing entrepreneurs. For example, within three years since firm birth, 80% of the founder-CEOs in our sample have either failed or have achieved the product-market and operating milestones that signal a transition to a standardized contract.

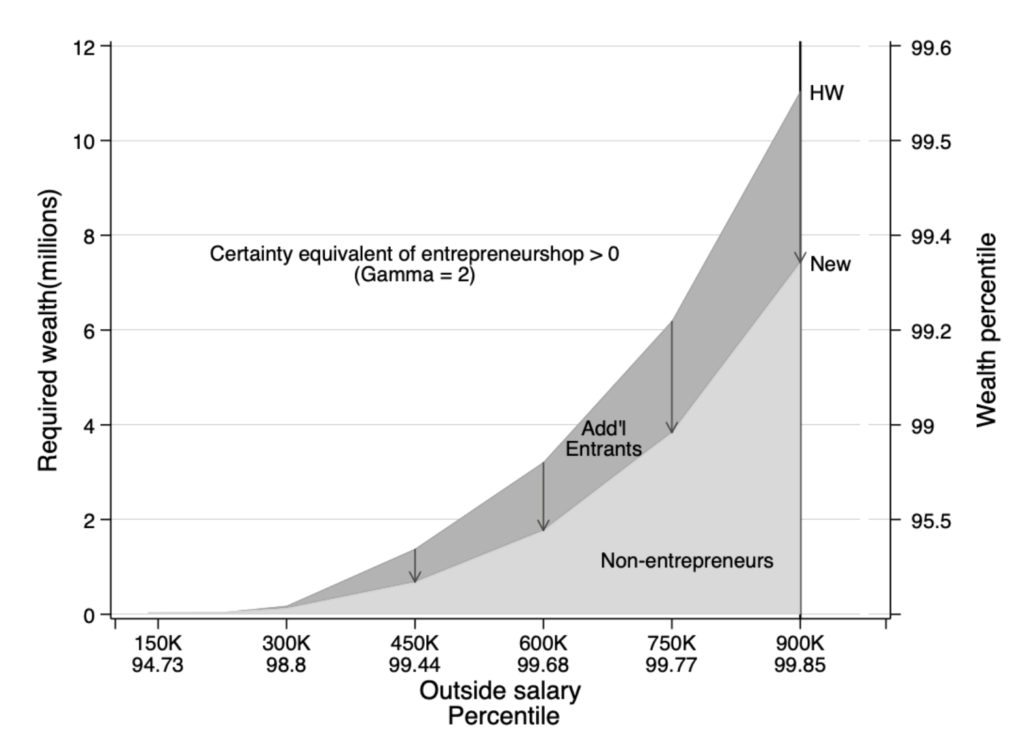

We next apply this insight of relatively quick resolution of uncertainty to Hall and Woodward (2010) analysis of the risk entrepreneurs face. We use their model to understand the conditions under which VC-backed entrepreneurship makes financial sense for an individual with standard levels of risk aversion. Figure 2 presents the results.

Figure 2: Comparison of Entrepreneurship Attractiveness Under Different Scenarios

This figure compares the certainty equivalent of entrepreneurship under a fixed contract with $150,000 in pay over the life of a venture (top line) to a contract where compensation increases with firm age due to milestones, taking moments from the Advanced HR data (bottom line). The coefficient of relative risk aversion is assumed to be 2. The area above each line is the region where the certainty equivalent is positive (i.e. individuals would be willing to become entrepreneurs). Hall and Woodward’s fixed contract is the solid line. The shaded region gives the additional entrepreneurship under our estimates.

The region above and to the left of each line is the area in Outside Salary-Wealth space where the certainty equivalent of entrepreneurship is positive. The line itself traces out the identity of the marginal entrepreneur under each model. The shaded region indicates the individuals for whom the implied payoff from entrepreneurship is positive using our modified compensation data compared to those in Hall and Woodward.

Finally, we validate the predictions of the model by studying the biographies and work histories of a sub-sample of founder CEOs. Consistent with evidence that founders of high-growth ventures have typically worked for several years prior to entering entrepreneurship, the average founder-CEOs are 36 years old and have nearly twelve years of pre-founding experience. Most founding CEOs of VC-backed startups were also in mid-level positions in their firms immediately prior to entry. Those with senior job titles or those among the higher paying jobs in their firms prior to entry are rarely seen in our data, suggesting that these individuals find the opportunity cost too great to make it worthwhile to experiment with entrepreneurship.

The results highlight an under-appreciated role played by venture capital investors– that of providing intermediate compensation to founders prior to an IPO or acquisition– which they might be uniquely positioned to do as hands-on investors who are able to resolve information asymmetry more effectively than passive capital providers. Nevertheless, our work also points to frictions at the very top end of the human capital distribution, where this intermediate liquidity provision may not be sufficient for the risk-adjusted return to VC-backed entrepreneurship to be positive.

The complete paper is available for download here.

Print

Print