David F. Larcker is the James Irvin Miller Professor of Accounting at Stanford Graduate School of Business; Brian Tayan is a Researcher with the Corporate Governance Research Initiative at Stanford Graduate School of Business; and Andrew C. Baker is a student at Stanford University School of Law. This post is based on their recent paper.

We recently published a paper, Environmental Spinoffs: The Attempt to Dump Liability Through Spin and Bankruptcy, that examines the practice of companies spinning off their environmental liabilities into separate companies that prove to be inadequately capitalized to meet their obligations.

A core tenant of economics is that the creation of shareholder and stakeholder value requires a complete and accurate accounting of the costs and benefits of business decisions. If costs are ignored or excluded, corporate decisions are distorted, leading to investment that might not otherwise be approved or would be priced differently. The omitted costs, however, do not disappear. They shift to parties not represented in the transaction—and are typically borne by society and redressed through taxation, lawsuits, or regulation. This problem is known as the externality problem.

Examples of externalities are plentiful. In the financial crisis, the risk of inadequately structured mortgage loans and securitizations ultimately fell on U.S. taxpayers. The aggressive marketing and prescription of opioid painkillers has led to the addiction and death of thousands of Americans. Oil and gas extraction through hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) has in some cases led to water and land contamination. And for many decades—leading up to and including today—industrial production has created byproducts that compromise land, water, or air quality, and require costly remediation. In all of these cases, society is the residual claimant, bearing the cost of outcomes that might never have occurred if they were properly included in the original business decision.

Of these, environmental externalities are perhaps the most vexing for corporate decision makers because of their pervasiveness and cost. Companies with a long history of operation and those that purchase factories with long histories have found themselves saddled with long-tail liabilities that might have been known, unknown, or downplayed in the past. Commercial byproducts once thought to be harmless might later be discovered to be toxic. The costs of environmental damage is not always easily quantifiable, and temptation might exist to defer costs that should be addressed now far into the future when they have a much lower present value (or when present management is no longer around to deal with these problems).

Still, environmental costs are a legal and moral obligation of the company and proper corporate governance requires that they be responsibly dealt with. Unfortunately, disturbing examples continue to occur where companies have taken aggressive action to separate their businesses from exposure to their legacy liabilities.

In this Closer Look, we examine the practice of spinning off environmental liabilities into separate companies that are inadequately capitalized to satisfy them, in what appears in retrospect to be an egregious attempt to avoid legal obligation. How widespread is this type of activity among companies with environmental liabilities? Are current mechanisms adequate to protect against it? Why is this behavior allowed as society is becoming more focused on the environmental and social objectives of corporations?

Environmental Spinoffs

Environmental liabilities are the legal obligation of the business that owns the asset that created them. A company cannot shed historical liability by shutting down the business or mothballing the facility that created it; it remains with the parent company. The only ways for a company to protect itself are to sell the business to new owners who assume liability, to resolve them through a bankruptcy process, or to spin off the assets into a separately traded company with the liabilities assigned.

In a spinoff, the company assigns assets, debt obligations, and continent liabilities to the subsidiary that will be spun off. The value of contingent liabilities (including environmental claims) is estimated by an outside firm that provides a range of values to management and the board, and the company accepts these values. If the contingent liability cannot be reasonably estimated, the company assigns no value for purposes of determining its liabilities and reserves. The company is afforded discretion in assigning contingent liabilities, just as it has discretion to assign debt obligations and determine the capital structure of the spinoff. However, at the time of separation, the company initiating the spin must demonstrate that the value of the spinoff company’s assets exceeds that of its liabilities (i.e., it must be solvent). Pro forma financials, including a description of contingent liabilities, are disclosed to investors through Form 10-12B.

Statement of Financial Accounting Standard (SFAS) Number 5 dictates the rules for recognizing the value of a contingent liability in financial statements: a liability will be accrued and expense recognized if the contingent loss is “probable” and the amount of loss can be “reasonably estimated.” If the loss is probable and the amount can only be recognized as a range, the company should recognize the best loss estimate. If all loss outcomes are equally probable, the company should recognize the lowest value. If the potential liability cannot be reasonably estimated, SFAS 5 requires that the company disclose the nature of the loss and not accrue a value. SFAS 5 was updated by Staff Accounting Bulletin Number 92 and again by Statement of Position 96-1, with additional guidance for recognizing the value of liabilities and determining materiality thresholds.

Research suggests that the value of environmental contingent liabilities disclosed in financial statements might not always be accurate and their description not fully transparent. Barth and McNichols (1994) use a model based on engineering cost estimates and site characteristics of known claims to estimate cleanup costs for sites that do not provide cost estimates for their liabilities. They estimate that liabilities average from 1 to 22 percent of the market value of equity, and that the value can deviate significantly from the liability implicit in the stock price depending on the assumptions used to determine how joint liabilities are shared among related parties.

Barth, McNichols, and Wilson (1997) find disclosure of environmental liability is surprisingly rare among firms that likely have liability based on their industry, suggesting that companies might be aggressive about not disclosing information about these claims—although Sarbanes Oxley increased disclosure practices subsequent to this study.

Safeguards exist to ensure that a company does not assign environmental liabilities to a subsidiary that it is insufficiently capitalized to meet its claims following spin off. Fraudulent conveyance prohibits debtors from transferring assets shortly before bankruptcy in order to keep assets out of reach of creditors. If this occurs, creditors are allowed to go back to the parent company for repayment (typically within a four-year period). Fraudulent conveyance applies to environmental liabilities.

Companies that spin off their environmental liabilities can defend against fraudulent conveyance by arguing that the spin company was solvent at the time of spin and rely on the solvency opinion of the third-party advisor to justify that assertion. Furthermore, Delaware courts do not allow the spinoff company to argue that it was overly indebted at the time of the separation, so long as it was indeed solvent. In addition, courts have ruled that companies do not need to follow an arms-length process when determining the capital structure of a subsidiary it is spinning off.

Research shows that companies can use aggressive maneuvers to disassociate themselves from environmental liability. Macey and Salovaara (2019) find that between 2012 and 2017 four of the largest coal companies in the U.S. were able to shed $5.2 billion in environmental and retirement liabilities through bankruptcy. They conclude that “companies are using the bankruptcy code to externalize costs onto third parties, despite statutes designed to force coal companies to internalize these costs.”

Vuillemey (2020) studies environmental damage in the context of the maritime shipping industry and identifies three practices that ship owners use to evade liabilities associated with their fleet. One, they shift ownership of ships with higher potential legal liability to a single-ship subsidiary. Two, they locate these ships in countries with weaker regulatory frameworks (flying under a so-called “flag of convenience”). And three, they sell ships immediately prior to their final voyage for the value of its raw materials and do not assume any responsibility for toxins or oil residues that eventually end up at sea when that ship is abandoned. He calls for a closer evaluation of the “liabilities and regulations that may be evaded or masked through networks of … subsidiaries.”

Shapira and Zingales (2017) use environmental pollution created by DuPont as a case study. They conclude that the pollution in that instance was net-present-value positive for shareholders (even in spite of the generated liability) because of the large time-mismatch between when pollution occurred and when it must be remediated. They argue that informational asymmetries are a key governance failure that allows environmental harm to occur: “One common reason for the failures of deterrence mechanisms is that the company controls most of the information and its release.”

To illustrate the problem, we review three examples of companies attempting to separate themselves from environmental liability through spinoffs.

Solutia

In 1997, Monsanto, the agricultural manufacturer known for the Roundup weed killer and genetically modified seed technology, spun off its chemicals business into a separately traded company called Solutia. The spinoff included businesses that made fibers, plastic interlays, specialty chemicals, performance materials, and intermediates. At the time of the spin, Monsanto obligated Solutia to bear responsibility for environmental and litigation costs associated with these businesses. Solutia had accrued $150 million in contingent liabilities and estimated that closure costs could add $70 million to that amount. In 1999, Monsanto merged with Pharmacia Upjohn, which retained Monsanto’s pharmaceuticals division and then spun off the agricultural business into a newly issued Monsanto company.

Solutia tried to grow through acquisition but the company’s results were challenged by weak economic growth and rising input costs. In December 2001, the company announced that it would take a special charge of $30 million to increase its environmental and self-insurance reserves.

Two weeks later, in an extensive front-page story, The Washington Post alleged that Monsanto had known for years of abnormally high PCB (polychlorinated biphenyl) levels near its plant in Anniston, Alabama, and that PCB was potentially carcinogenic. Monsanto had been the dominant producer of PCBs for decades, a chemical product used in a vast number of commercial and industrial products, and produced PCB at the Anniston plant from 1935 to 1971. The EPA banned PCB in 1979.

The article alleged that Monsanto regularly released waste materials into creeks near the Anniston plant. By the late 1960s, managers noticed that fish were dying in adjacent waterways. The company conducted water tests and determined that PCB levels were 7,500 times the legal limit, and internal studies found that PCB might be carcinogenic. Company documents showed that management had debated these issues and considered actions ranging from “sell the hell out of them as long as we can” to stopping production immediately. The company opted for a middle approach: gradually reducing PCB production while searching for a replacement product. The company stopped making PCBs in the 1970s, the plant was refitted for other production, and Monsanto engaged in remediation actions in the 1980s and 1990s. Still, local residents reported clusters of cancer cases near the plant and blood tests showed residents had elevated levels of PCBs in their blood.

Solutia’s stock fell 25 percent the day the article was released. A spokesperson acknowledged that the company had made mistakes in the past, but stressed that it was unfair to judge the company’s previous behavior using modern standards: “Did we do some things we wouldn’t do today? Of course. But that’s a little piece of a big story. If you put it all in context, I think we’ve got nothing to be ashamed of.” The company said that it was adequately reserved for all potential environmental and legal liability. One research analyst challenged this assertion: “The hard part is, how do you define what the potential liability is? They don’t tell you what their insurance coverage is. They have self-insurance, and they don’t tell you how much they have.”

In 2002, an Alabama jury ruled against Solutia and Monsanto in a case filed by local residents, requiring them to repay property damage for PCB contamination. Monsanto argued the claims should be borne by Solutia, but noted that some share could be assigned to them: “We’re not in a position to quantify around a Solutia liability.”

Meanwhile, Solutia’s financial condition continued to deteriorate, and in 2003 the company declared bankruptcy. Solutia sued Monsanto, alleging that Monsanto assigned it “onerous” environmental and employee benefit obligations at the time of separation. Monsanto responded, “We will not take any obligations that are not ours.” The courts, however, determined that Monsanto’s obligations were substantial. Over the following two-year period, Monsanto accrued $600 million for Solutia-related matters. When Solutia finally emerged from bankruptcy in 2005, Monsanto contributed an additional $250 million in investments in the firm, and was given a 30 percent equity stake in the newly capitalized company. In 2012, Solutia sold to Eastman Chemical for $3.4 billion (see Exhibit 1).

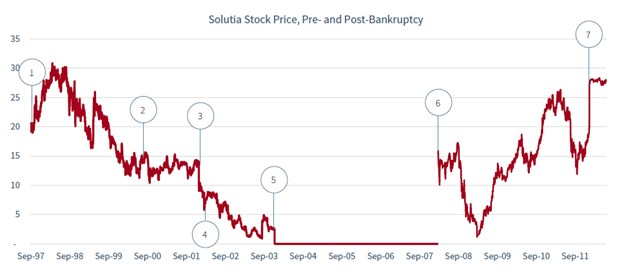

Exhibit 1: Solutia Stock Price History

- Solutia spun off from Monsanto

- Monsanto merges with Pharmacia and spun off as new Monsanto

- Washington Post publishes article about Monsanto’s environmental practices in Alabama

- Jury rules against Monsanto and Solutia in Alabama environmental case

- Solutia declares bankruptcy

- Solutia emerges from bankruptcy

- Eastman Chemical agrees to purchase Solutia

Source: Stock prices from the Center for Research in Security Prices.

Tronox

In 2005, oil-exploration company Kerr-McGee spun off Tronox, its chemical subsidiary responsible for producing titanium dioxide—a white pigment widely used in industrial and consumer products. The separation took place in a two-part transaction, with Kerr-McGee issuing shares in Tronox through a partial IPO in 2005, followed by a spinoff of the remaining shares in 2006. Tronox’s listing documents valued its reserved environmental liabilities at $239 million. The master separation agreement stipulated that Kerr-McGee would reimburse Tronox for environmental liabilities incurred in excess of reserves, but it capped Kerr-McGee’s maximum obligation at $100 million.

Three months after the spin, Anadarko agreed to purchase Kerr-McGee for $16 billion in cash. The deal was priced at a 40 percent premium. Kerr-McGee’s CEO received a payout of almost $200 million.

In 2009, Tronox declared bankruptcy, faced with a major decline in demand following the financial crisis. The company sued Anadarko, alleging it was inadequately capitalized at the spin. In an unusual twist, Tronox disclosed that it was not only responsible for shouldering environmental liabilities associated with its core titanium oxide business, but also that it was saddled with the environmental liabilities of Kerr-McGee’s other discontinued chemical operations. Court documents demonstrated that Kerr-McGee had unsuccessfully been able to participate in merger activity in the oil and gas industry in the 1990s because potential buyers did not want to assume its non-oil liabilities. As early as 1998, Kerr-McGee had been considering transactions to separate itself from these liabilities. In 2001, as EPA-mandated remediation increased, the Kerr-McGee board of directors approved the creation of a “clean” holding company. In 2003 and 2004, Kerr-McGee began a process of removing assets from its chemicals business while assigning liabilities to entities that eventually would become Tronox. The company only disclosed some of these assignments to the public.

In 2005, Kerr-McGee actively tried to sell Tronox. However, potential buyers demanded a dramatically reduced price for the business if environmental liabilities were included. One private-equity consortium proposed a purchase price of $1.2 billion for Tronox without environmental liabilities, but only $300 million if those liabilities were included—implying a $900 million value for liabilities in excess of reserves. According to the lawsuit, Tronox argued this valuation discrepancy demonstrated that Tronox’s reserves at the time of separation were “woefully inadequate.” Furthermore, Tronox disclosed that the independent firm used to issue a solvency opinion at the spinoff relied entirely on Tronox officers to determine its contingent liabilities without independent verification.” The lawsuit concluded: “Overburdened with the legacy liabilities and debt, stripped of essential cash, and grossly undercapitalized, Tronox was doomed to fail.”

U.S. prosecutors and the EPA joined the lawsuit, arguing that “the avoidance of environmental debts to the government, and the stripping of assets that could have satisfied those debts, were fraudulent conveyances.”

Kerr-McGee parent Anadarko refuted the allegations, pointing to Tronox’s successful IPO as evidence that it was solvent at the time of separation.

In 2011, Tronox emerged from bankruptcy, and a litigation trust for creditors took its place as plaintiff in the case against Anadarko (see Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Tronox and Kerr-McGee Stock Price Histories

- Kerr-McGee completes partial IPO of Tronox

- Kerr-McGee spins off remaining share of Tronox

- Anadarko agrees to purchase Kerr-McGee

- Tronox declares bankruptcy; sues Anadarko; U.S. prosecutors join lawsuit

- Tronox emerges from bankruptcy; litigation trust takes its place as plaintiff against Anadarko

Source: Stock prices from the Center for Research in Security Prices.

Two years later, the judge ruled that Anadarko and Kerr-McGee acted with “intent to hinder” when Tronox was spun off. The judge also ruled that the environmental trust was entitled to receive $14.17 billion, an amount that Anadarko might be able to have reduced by $9 billion for offsetting costs incurred in the transaction. He set a floor of $5.15 billion. Anadarko stock fell 6 percent on the ruling. One year later, however, the final amount was set at the floor amount of $5.15 billion, and Anadarko stock rose 15 percent. Tronox continues to trade as a standalone company (see Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: Anadarko Stock Price History

- Anadarko agrees to purchase Kerr-McGee

- Tronox sues Anadarko

- Judge rules that Anadarko and Kerr-McGee acted with “intent to hinder”

- Judge sets final settlement amount at $5.15 billion

Note: Anadarko stock price adjusted for 2-for-1 split May 2006.

Source: Stock prices from the Center for Research in Security Prices.

Chemours

In 2015, DuPont spun off certain specialty chemicals businesses into a separately traded company called Chemours. Chemours produced fluoroproducts (the most famous of which was marketed under the brand name Teflon), titanium dioxide, and other performance chemicals.

Within the first year following separation, Chemours lost three consecutive jury cases finding that perfluorooctanoic acid (otherwise known as PFOA or C-8, an input chemical used in the production of Teflon) was responsible for a range of diseases, including cancer. While the individual awards were small (amounting to several hundred thousand dollars to a few million each), the number of cases exceeded 3,400. One short-selling research firm suggested that Chemours’s environmental liabilities and large debt load ($4 billion) could push it into bankruptcy. Chemours stock price instead rose steadily.

In 2017, the company, jointly with DuPont, agreed to pay $671 million in cash to settle certain outstanding claims involving PFOA—with each company responsible for half of the settlement. Chemours general counsel called the settlement a “sound resolution.”

This settlement, however, did not even begin to put Chemours’ legacy liabilities behind it. In 2019, the company sued its former parent alleging that the actual value of environmental liabilities far exceeded those reported by DuPont at the time of the spin. For example, Chemours alleged that environmental claims in a North Carolina facility would amount to $200 million, 100 times larger than the $2 million estimate made by DuPont. Similarly, liabilities in a New Jersey facility far exceeded the $337 million estimate. PFOA liabilities, which were partially settled for $671 million and continued to accrue, were not even valued at the time of spin because “the liabilities were so volatile and potentially huge” that company accountants would not attempt to estimate their value. In total, Chemours disclosed that it faced over $2.5 billion in environmental claims—an amount five times larger than its accruals at spin. Furthermore, these liabilities stemmed from business lines unrelated to performance chemicals, including DuPont’s legacy exposure to explosives, asbestos, and benzene litigation. In aggregate, Chemours was responsible for two-thirds of DuPont’s environmental liabilities but received only 19 percent of its business lines—this in addition to $4 billion in assigned debt. Chemours asked the judge to hold DuPont liable for amounts in excess of estimated liabilities at the time of the spin.

The judge ultimately dismissed the lawsuit—ruling he had no jurisdiction to hear the case—and sent the matter to arbitration as stipulated by the separation agreement. A settlement has not yet been reached (see Exhibit 4).

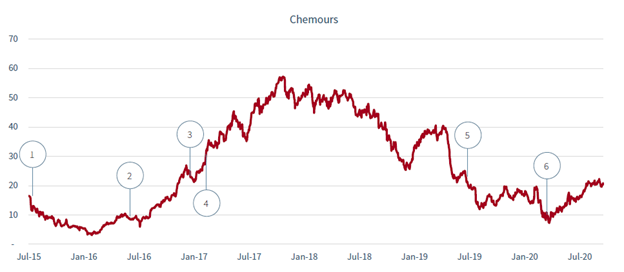

Exhibit 4: Chemours Stock Price History

- DuPont spins off Chemours

- Short-seller argues that Chemours is inadequately capitalized to handle liability and debt

- Chemours loses third case for PFOA environmental liability

- DuPont and Chemours jointly agree to settle PFOA liabilities

- Chemours sues DuPont

- Judge dismisses lawsuit against DuPont; sends complaint to arbitration

Concluding Remarks

The cases of Solutia, Tronox, and Chemours highlight a troubling practice of companies attempting to separate themselves from environmental liability through the spinoff of thinly capitalized subsidiaries.

First, we see the example of at least one company knowingly engaging in polluting activities where, from a net present value perspective, the cost of being held liable for pollution in the future is lower than the current cost of abatement. Second, reputational considerations contribute to decisions to pollute (because the management that pollutes will likely be retired by the time of detection and may not bear the negative reputational consequences) and to decisions to separate environmental liability through spinoff (because the parent company can claim disassociation from the polluting activity after divesting the subsidiary). Third, management that completes the spinoff has opportunity for compensation gain if they can avoid equity losses in a spinoff that goes bankrupt or through sale of the “clean” company at a premium; these compensation gains are unlikely to be subject to clawback when future environmental liability is assessed. Fourth, informational asymmetries weaken the disciplining role of shareholders and stakeholders because these parties have considerably less visibility than management into the magnitude and likelihood of potential liability. Fifth, the statute of limitations on fraudulent conveyance introduces the potential that malfeasance will not be discovered until after the statute of limitations has lapsed.

The combination of these features provides a socially undesirable channel for companies to avoid the externalities produced by their environmental actions.

Why This Matters

- Companies are required to provide estimates of the probable value of their environmental liabilities in their disclosure statements, and yet as we have seen in this Closer Look, actual remediation amounts can differ widely from these. How rigorous, accurate, and reliable are these estimates? Do companies take advantage of accounting rules for reasonableness to low-ball estimates? Does the risk of having a weakened negotiating position with claimants give companies incentive to downplay their exposure?

- Courts have ruled that companies have leeway to determine the capital structure of a spinoff, including the assignment of liabilities, so long as the newly formed company is solvent. Companies are also allowed to assign environmental liabilities to a spinoff that are entirely unrelated to its ongoing line of business. Are these rules fair and reasonable? Are restrictions against fraudulent conveyance strict enough to prevent companies from assigning liabilities that a spinoff ultimately cannot handle? Should Congress change rules so that environmental liabilities can more easily be put back to the former parent?

- The board of directors is responsible for reviewing and approving the business line, capital structure, and contingent liabilities of a spinoff. How reasonable are the estimates that management presents to the board for approval? How much of the underlying analysis do they see? Does the reliance on a third-party for these estimates lessen the board’s willingness to challenge management on the reasonableness of these estimates?

- Companies today are facing heightened pressure to consider stakeholders when making long-term business decisions (for example, under ESG). Does the practice of spinning off environmental liabilities run counter to this? Would greater consideration of stakeholder interests compel managements and boards to more responsibly deal with the environmental obligations created by their business?

- In the three examples in this Closer Look, the parent companies that completed spinoffs eventually were required to make payments to resolve their environmental liabilities. Did the companies experience a net positive impact from their actions, or did they end up fully paying the externality costs they created?

The complete paper is available for download here.

Print

Print