Peter Reilly is Senior Director of Corporate Governance at FTI Consulting. This post is based on his FTI memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here); For Whom Corporate Leaders Bargain by Lucian A. Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel, and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here) and Restoration: The Role Stakeholder Governance Must Play in Recreating a Fair and Sustainable American Economy—A Reply to Professor Rock by Leo E. Strine, Jr. (discussed on the Forum here).

Background

Over the past decade, there has been growing pressure on management and Boards from stakeholders to pursue a longer-term orientation in decision-making. The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare the fact that companies ill-prepared to address significant external risks are unlikely to have the resilience and ability to deliver returns to stakeholders over the long-term. That, together with the broad guidance provided by the Paris Agreement has resulted in a heightened focus on whether companies are effectively overseeing, managing and, ultimately, mitigating climate-related risks in their business models. One outcome of these developments has been the rise in references to the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (‘TCFD’), a voluntary reporting framework that has acted as a guide in a space where there remains an absence of common international climate-related reporting standards.

Late in 2020, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) announced [1] it would become the first economy in the world to make the TCFD mandatory, following on from New Zealand’s announcement [2] that the TCFD recommendations would apply to the financial services sector. Initially, the rules apply to premium listed companies on the London Stock Exchange—of which there are 465 excluding investment funds—from 1 January 2021, with an outline timeline that most other companies will be reporting against TCFD by 2023. Shortly thereafter, the Financial Reporting Council (FRC), author of the UK Corporate Governance Code (the “UK Code”), published its review of climate disclosure at UK companies, [3] concluding that “corporate reporting needs to improve to meet the expectations of investors and other users on the urgent issue of climate change”. The FCA’s CEO said the introduction of the TCFD recommendations “must be complemented by more detailed climate and sustainability reporting standards that promote consistency and comparability.” [4] Likewise, the FRC said it supports “the introduction of global standards on non-financial reporting”. [5] However, until that happens, it recommended reporting “against the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures’ recommended disclosures and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) metrics for their sector.” While the International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”) Foundation’s consultation on sustainable reporting closed at the end of 2020, confirmation and implementation of such standards is unlikely over the short-term.

In its most recent Status Report, [6] released in October 2020, the TCFD announced that verbal commitments to its recommendations had grown by 85%, with 60% of the world’s 100 largest companies reporting against the recommendations.

In this post, and in light of the scrutiny on sustainability reporting, climate disclosure and, specifically, the TCFD, we take a look at wider market developments before analysing the extent of its adoption in the UK market in the period up to 2021 and setting out the key aspects of the TCFD.

Market Pressure: The Investor Viewpoint

With the absence of clear regulatory and reporting guidance, TCFD appears to have gradually become the preeminent framework for climate-related disclosure at listed companies. Nonetheless, outside of the focus on TCFD as filling the vacuum of climate-related disclosure obligations, the pressure on companies from investors has continued to rise. For a decade, the level of scrutiny on companies’ approaches to overseeing and managing climate risks and opportunities from capital market participants has increased incrementally. COVID-19 has acted as a further catalyst for the rapid rise in prominence of ESG factors for investors and public companies.

In January 2020, Blackrock set the scene by asking all of its investee companies to report against the TCFD and SASB frameworks. In 2021, the impact of the annual letter from CEO Larry Fink was arguably reduced, as Blackrock’s statement was only one of a host of significant announcements from major investors around the world. The below table sets out some of the pronouncements made by major institutions and the heightened focus on climate in general:

| Investor | Assets Under Management | Announcements in the First Two Months of 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| Amundi | €1.65 trillion | Stated its expectation that some of Europe’s largest companies will vote against executive pay packages that are not explicitly linked to certain ESG goals. |

| Aviva | £334 billion | May divest from oil, gas, mining, and utilities companies that do not meet its expectations on tackling climate change. |

| BlackRock | $8.67 trillion | Stated its expectation that the companies it invests in that they will need to show how they plan to survive in a world aiming for net-zero by 2050. |

| Investment Association | n/a | Stated it will flag for the first time when companies in high-risk sectors fail to report under the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. |

| State Street | $3.15 trillion | Noted in January that the main priorities for 2021 would be addressing systemic risks associated with climate change and the lack of racial diversity. |

| Vanguard | $6.7 trillion | Has said that its patience with companies on climate action is “running short” and it expects to “be very intentional about voting” on the matter in 2021. |

Voting on Climate

It appears there will be growing pressure on Boards to act through proxy voting, with most of the world’s largest investors now incorporating climate-related expectations into their proxy voting guidelines. However, over the past six months, there has been a slow but growing movement taking place among companies themselves: voluntarily providing shareholders with a vote on climate strategy—a ‘Say on Climate’, led by a number of initiatives.

In further evidence of the gap between the market and regulators on this issue, the following are examples of companies from across the globe that will be putting a Say on Climate vote to shareholders in the coming months:

Source: https://www.sayonclimate.org/supporters/

There is a balance to be struck for companies when taking on additional votes at general meetings. Those acting first in this space are likely to be those with robust strategies and messages already in place. The same companies will simultaneously receive the most latitude from a shareholder base and proxy advisors that are unlikely to be fully prepared to evaluate and vote against the proposals, although shareholder proposals across the globe may have provided a testing ground of sorts. These steps will drive far greater levels of engagement though, much like the imposition of ‘Say on Pay’ regulations did. In the corporate governance and ESG space more so than anywhere, once a cohort of companies are perceived to act in a shareholder friendly manner, those same shareholders become emboldened to expect the same level of interaction and engagement at other companies. Meanwhile, regulators will be watching intently and may feel similarly energised to build on market practice and put forward requirements that a Say on Climate becomes a permanent fixture of the proxy voting landscape. Perhaps, in the UK at least, TCFD will point toward best practice in seeking shareholder approval of such proposals.

What is the TCFD?

The TCFD was established in 2015 by the Financial Stability Board in order to focus specifically on climate change and capital markets. The potential for assets to be mispriced and capital to be misallocated was one of the driving reasons for the establishment of the TCFD, with the Taskforce seeking to enhance the quality of information provided, allowing all market participants to evaluate and manage risks and opportunities. Following two years of review and an 18-month consultation, in June 2017, the TCFD published a final report setting out its recommendations under four pillars:

- Governance

- Strategy

- Risk Management

- Metrics and Targets [7]

Under the pillars, there are a total of 11 recommended disclosure obligations. In a similar vein to the overarching aims of all disclosure and reporting requirements, the goals of the TCFD recommendations are dual purpose. They are not just related to providing enhanced information to market participants, but also to promote greater identification and management of climate-related risks and opportunities which, in turn, can strengthen policies, programmes, practices and behaviours inside companies and among management and Boards.

Importantly, within the final recommendation, the TCFD demands slightly more of companies. In addition to disclosing backward-looking sustainability data, (e.g. greenhouse gas emissions or water usage), a company is also required to take a forward-looking approach and disclose the financial impacts of climate-related risks and opportunities on its business model. In an effort to shift away from reactive reporting and disclosure, TCFD aims to challenge companies not to report on how their activities are impacting the environment, but how climate change will impact their business.

The two key types of climate-related risk which companies need to consider for these purposes are:

- Transition Risks: These are the risks relating to the transition to a lower-carbon economy, such as policy changes reputation impacts, and shifts in markets, norms and technology.

- Physical Risks: These are the risks relating to the physical effects of climate change itself and can be event-driven or longer-term shifts in climate patterns, including direct damage to assets changes in water availability; and extreme temperature changes affecting companies’ premises, operations and employee safety.

On the other hand, climate-related opportunities might range from resource efficiency and cost savings, adoption of lowemission energy sources, to development of new products and services, and access to new markets. Regardless, if market participants and company stakeholders are not provided with the requisite information, it becomes difficult to assess the presence of those risks and opportunities. Likewise, if Boards and management are not consistently evaluating them, they may be caught off guard and a risk may materialise to the detriment of their business and their stakeholders; or, there may be an opportunity to protect and enhance value that is not captured.

As outlined, there remains a lack of clear regulatory guidance in this space; however, the expectation is that TCFD disclosures are made in the core financial filings of reporting companies (i.e. Annual Reports), where the most important information regarding a company is provided. Supporting information can, of course, be provided in supplemental locations, such as sustainability or TCFD reports, which we have taken into account later in our report. Our core analysis reflects disclosure in the Annual Report, where climate relate disclosures should be provided if they are afforded the same level of importance as ‘traditional’ business risks.

Reporting Requirements in the UK

The implementation of the TCFD recommendations had previously been a voluntary step for UK companies. Depending on sector or the direction from which stakeholders exerted pressure, those disclosures could be disparate in nature, failing to achieve the overarching goals of provision of information to the market.

On 9 November 2020, HM Treasury published an interim report [9] confirming the UK Government’s intention to roll out mandatory TCFD-aligned climate disclosures across the economy by 2025, with a significant portion of mandatory requirements in place by 2023. In December, the FCA published a policy statement confirming that, under a new Listing Rule (in LR 9.8), commercial companies with premium listings must state in their Annual Report, for accounting periods beginning on or after 1 January 2021, whether they have disclosed in line with the TCFD’s recommendations. To the extent they have not, they must explain why and describe the steps that will be taken in order to make the relevant disclosures in future and the associated timeframes (i.e. largely consistent with the long-standing ‘comply or explain’ principle of the UK corporate governance regime).

The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) is currently consulting [10] on how and when to extend climate-related disclosure obligations to other companies in the UK. The expectation is that TCFD disclosures will, over time, become mandatory for more companies in the UK. In taking these steps, the FCA has elevated the reporting requirements of TCFD to the same level as the UK Code, which sets out best practice for all main market UK companies as well as generally informing the voting practices of investors.

State of Play: Market Reporting Review

As outlined, UK companies will be required to comply (or explain why they have not) with the requirements of the TCFD, starting with premium listed companies for all accounting periods commencing on or after 1 January 2021. In this section, we detail the state of play for current reporting against the TCFD’s requirements, the growth in doing so since 2017 and a breakdown of the type of disclosure provided by UK publicly listed companies up to December 2020. Overall, while the growth in referencing the framework of TCFD has been notable, the variety of disclosure continues to present challenges for market participants; and, may well do the same for regulators.

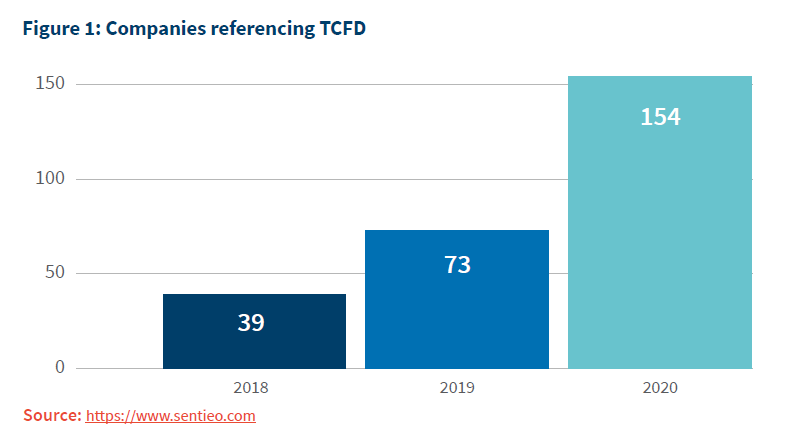

Since the finalisation of the TCFD’s recommendations in 2017, there has been a relatively rapid rise in references to the TCFD in UK reporting.

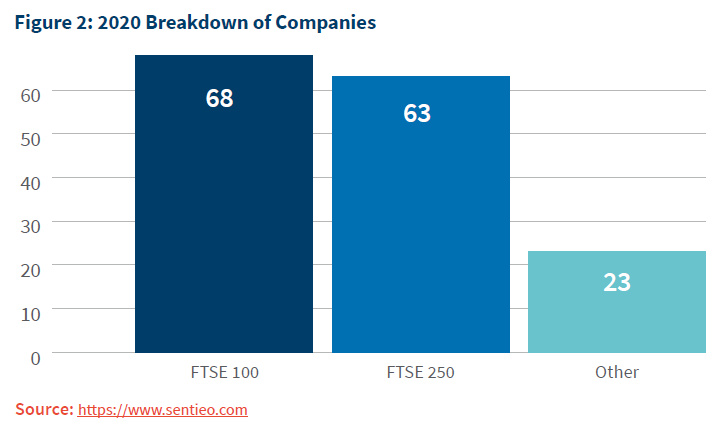

In reviewing 2020 reporting, larger companies were more likely to reference the disclosure requirements of the TCFD, with over two thirds of the UK’s 100 largest companies at least alluding to the importance of TCFD, indicating a potential resource gap between the largest companies and those outside of the FTSE 350:

That statistic could be viewed more worryingly—that companies review of climate-related risks, or consideration of the TCFD framework is a ‘nice to have’; an element of overseeing business that arrives when resources become available, as opposed to being truly integrated throughout the company’s governance and risk framework. Indeed, it is noteworthy the significant drop off from the FTSE 100 to FTSE 250, although the figures do not include investment trusts and funds. Nonetheless, while risk disclosure has always tended to be more detailed at larger companies, climate change and the associated transitional or physical risks will not differentiate by the size of a company, just as ‘traditional’ risks do not.

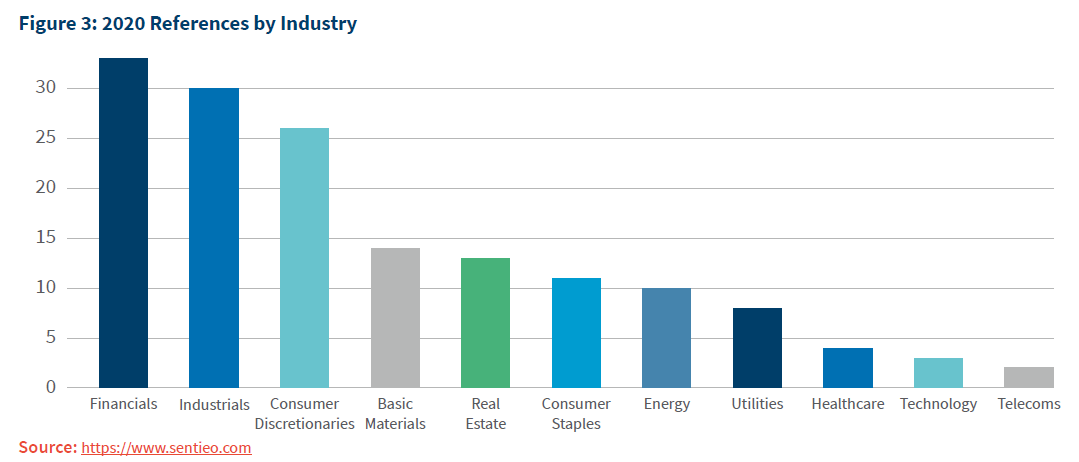

Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, [11] companies in the financial sector most frequently reference the provisions and recommendations of the TCFD, potentially reflecting the importance of the issue to UK asset managers as well as their tendency to be at the forefront of global best practice. It is also a recognition of how climate risk is not limited to those sectors more traditionally associated with it, such as those in more resource or energy intensive industries.

Indeed, the initial focus of the TCFD, on the potential for mispricing of assets due to incomplete information, may well have been most readily taken onboard by the UK financials industry, although the figures are also reflective of the number of companies in each industry on the London Stock Exchange. Either way, as regulatory and stakeholder demands rise, so must reporting across a host of industries.

The Nature of Disclosure

Due to its voluntary nature and the absence of regulation, there remains a wide variety in the approaches to disclosure against the TCFD framework, ranging from fleeting references to extensive reporting against each recommendation complete with scenario analyses and forward-looking performance targets. Indeed, the TCFD itself—in its 2020 Status Report—states that in analysing the top 100 companies reporting against the framework, “the Task Force did not evaluate the extent or quality of a company’s TCFD reporting but rather identified whether the company indicated it reported in line with the TCFD recommendations or planned to.”

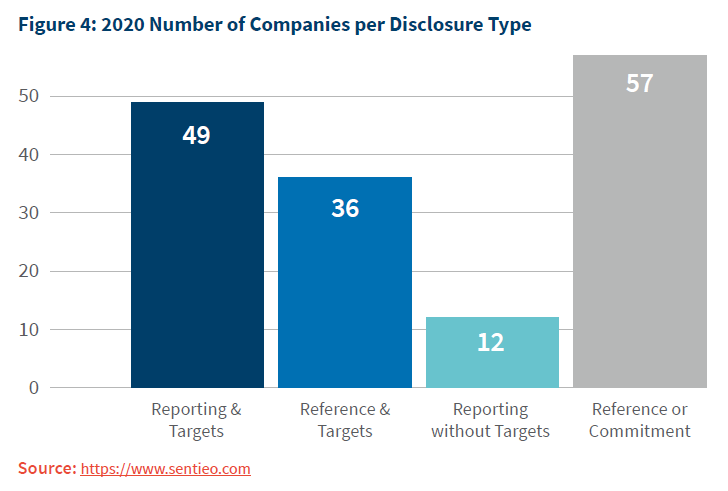

While the pressure to act in this space will ensure less latitude for companies going forward, the disclosure of a number of companies appears to point toward reporting against the TCFD’s framework without necessarily providing the requisite disclosure and detail of integration throughout the business’ framework. In analysing the reporting of UK companies, we separated disclosures into four different groups. As per the expectations of TCFD, while we accepted supplemental information (on scenario analysis and targets, for example) from other sources, without a reference to TCFD in a regulatory filing, companies were not included in our analysis.

| Type of Disclosure | Details |

|---|---|

| Reporting & Targets (most detailed) | Companies that provide extensive disclosure under each of the recommendations of the TCFD; set and monitor data; and, incorporate climate-related targets. |

| Reference & Targets | Companies that reference the TCFD and set climate-related targets without reporting extensively under its framework. |

| Reporting without Targets | Companies that provide extensive disclosure under each of the first three of the four pillar TCFD recommendations but have not established climate-related targets. |

| Reference or Commitment (least detailed) | Companies that merely refer to the TCFD framework or commit to disclosing against it in future years, as well as those that simply point to CDP and wider initiatives. |

It is informative that of the 154 UK companies referencing TCFD in their reporting in 2020, only a minority include detailed reporting against each of the four areas, including metrics and targets. Given the remainder of UK companies fail to reference TCFD in regulatory filings, a large amount of companies may have to do a significant amount of work to not only meet revised regulatory and market expectations, but to fundamentally shift their approach to overseeing and mitigating climate-related risk. While firmer guidance as to what constitutes reporting “compliance” against TCFD is yet to come, as investor and regulatory sophistication rises, the ability of companies to simply point to TCFD in an Annual Report will end; and, those that made references or commitments in 2020 will be expected to shift to one of the more meaningful approaches in 2021 and 2022.

Most stakeholders, and the TCFD itself, recognise that companies cannot incorporate all of the requirements—both in letter and in spirit—of the framework overnight. As such, making a commitment to greater integration does not necessarily constitute bad practice, but the window for enhanced disclosure is closing. Similarly, there are likely to be companies that have taken rigorous approaches to climate without necessarily incorporating the TCFD framework into reporting. Indeed, companies may have integrated climate risks into their processes well ahead of the finalisation of the TCFD. Nonetheless, those companies that have been silent in this space will have to take significant steps over the coming nine months to ensure their reporting requirements are developing in line with stakeholders’ expectations and regulatory demands.

TCFD Principles

There are four pillar recommendations of the TCFD, with guidance provided under each pillar as to how companies can meet their obligations. Some, however, have proven more difficult than others. In its 2020 Status Update, the TCFD pointed to the forward-looking disclosures under the Strategy pillar and the disclosures under the Metrics and Targets pillar as being most useful for making financial decisions; however, unsurprisingly, these two pillars are also generally considered to be the most challenging of the four to implement for companies. [12] In reporting against these pillars, companies are also required to conduct an assessment of materiality, one of the most important concepts in reporting of any nature, not just sustainability.

As a means of gradually preparing for full disclosure against the recommendations, the governance and risk management pillars present less burdensome requirements, and can provide a foundation before further enhancements are made through reporting against the Strategy and Metrics and Targets pillars in subsequent years. The TCFD has developed seven principles for effective disclosure, which are largely consistent with other internationally accepted frameworks for financial reporting and are generally applicable to most providers of financial disclosures:

- present relevant information;

- be specific and complete;

- be clear, balanced and understandable;

- be consistent over time;

- be comparable among companies within a sector, industry or portfolio;

- be reliable, verifiable and objective; and

- be provided on a timely basis.[13]

The principles outlined should not come as a surprise to individuals charged with reporting for companies. Much like accounting requirements and general corporate reporting, the principles are underpinned by the goal of providing material and meaningful information in a comparable fashion to those seeking to digest the disclosure.

The Four Pillar Recommendations

The four pillar recommendations of the TCFD are interlinked and while there is certainly an avenue to gradually integrate them into corporate governance and strategy, the ability for companies to ‘cherry pick’ which aspects of the framework to report against is waning. While the TCFD provides separate guidance for specific sectors, the following section shines a light on each of the pillars, which have sub-sections providing guidance to reporting companies from all sectors.

Governance

Under this pillar of the TCFD, the overarching recommendation is for a company to disclose “how climate-related risks and opportunities are assessed by the company’s management and overseen by the Board” so that market participants can assess whether climate-related issues are receiving appropriate Board and management attention.

There are two specific disclosures required:

(a) Describe the Board’s oversight of climate-related risks and opportunities

This should set out the processes and frequency by which the Board and its committees are informed about climate-related issues and the extent to which these are considered when reviewing and guiding strategy, major plans of action, risk management policies, annual budgets, and business plans. The disclosure should also consider monitoring and progress against goals and targets for assessing climate-related issues.

(b) Describe management’s role in assessing and managing climate-related risks and opportunities

This should explain whether the company has assigned climate-related responsibilities to management or committees and whether those committees report to the Board, as well as how management is informed about climate-related issues and how it monitors performance. This requirement also expects descriptions of the company’s organisational structure.

Strategy

Under this pillar of the TCFD, which arguably expects the most of companies, the overarching recommendation is for a company to disclose “how the company’s strategy and financial planning will or may be impacted by climate-related risks and opportunities based on different climate scenarios”, for example by affecting demand for its products and services or its supply chain, which, in turn, would have financial consequences for the company.

There are three specific disclosures required:

(a) Describe the climate-related risks and opportunities the organisation has identified over the short, medium and long term

In a similar vein to the established viability statement, this requires an explanation of what the company considers to be its relevant short, medium and long-term time horizons, taking into consideration the useful life of the company’s assets and infrastructure and the fact that climate-related risks often manifest themselves over the medium or long-term. For each time horizon, a description of the specific climate-related issues that could have a material financial impact on the company is then required.

(b) Describe the impact of climate-related risks and opportunities on the organisation’s businesses, strategy and financial planning

This subsection requires discussion of the impact of the climate-related issues identified in the company’s businesses, strategy and financial planning. Detail should also be provided regarding the impact of such issues on the company’s products and services, supply chain and/or value chain, adaptation and mitigation activities, R&D investments and operations. A key element of this guidance is the expectation that companies provide a description of how such issues are integrated into the company’s financial planning process, specifically the impact on its operating costs and revenues, its capital expenditure and its access to capital.

(c) Describe the resilience of the organisation’s strategy, taking into consideration different climate-related scenarios, including a 2°C or lower scenario

One of the more challenging—but equally, most important—pieces of guidance, this section asks companies to carry out ‘scenario analyses’ on a future 2°C or lower scenario and at least one other scenario; the aim being an evaluation of the company’s resilience to climate-related issues. Organisations are expected to discuss where they believe their strategies may be impacted by climate-related risks and opportunities; how their strategies might change to address such potential risks and opportunities; and, the climate-related scenarios and associated time horizon(s) considered.

One of the key findings of the TCFD’s 2020 Status Report was that only one in 15 companies reviewed disclosed information on the resilience of its strategy in these scenarios. The review found that the percentage of companies disclosing the resilience of their strategies, taking into consideration different climate-related scenarios, was significantly lower than that of any other recommended disclosure.

The TCFD recognises that this may be a qualitative exercise for many companies, but stresses that companies which are particularly exposed to transition or physical risks should take a more rigorous approach. In situations where a company is not certain information related to its scenario analysis assumptions or the resilience of its strategy contains confidential business information, TCFD encourages the company to consider a stepwise approach to disclosure—rather than decide not to disclose. For example, a company might start by disclosing broader, qualitative information and move to more specific, quantitative data and information over time. To further assist, on the back of commitments in its 2019 status update, the TCFD has published Guidance on Scenario Analysis for Non-Financial Companies.

Risk Management

Under this pillar of the TCFD, the overarching recommendation is for a company to disclose “the company’s processes to identify, assess and manage climate-related risks”, including “both physical risks from climate change and transition risks to adapt the business to a low carbon economy” so that market participants can understand how a company’s strategic thinking on climate-related issues is integrated into its day to day risk management processes.

There are three specific disclosures required:

(a) Describe the organisation’s processes for identifying and assessing climate-related risks

This should include an explanation of how the company determines the relative significance of climate-related risks in relation to other risks and whether the company considers existing and emerging regulatory requirements related to climate change (e.g. limits on emissions) as well as other relevant factors. The company should also disclose its processes for assessing the potential size and scope of identified climate-related risks, its definitions of risk terminology used (or references to existing risk) and the classification frameworks used.

(b) Describe the organisation’s processes for managing climate-related risks

Companies should describe their processes for managing climate-related risks, including how they make decisions to mitigate, transfer, accept, or control those risks. In addition, they should describe their processes for prioritising climaterelated risks, including how materiality determinations are made.

(c) Describe how processes for identifying, assessing, and managing climate-related risks are integrated into the organisation’s overall risk management.

There is less guidance on the parameters of this disclosure requirement from the TCFD, which largely replicates the statement above, and asks organisations to describe the processes for integration of climate-related risks into the company’s existing risk management framework.

Metrics and Targets

Under this pillar of the TCFD, the overarching recommendation is for each company to disclose “the metrics and targets used to assess and manage relevant climate-related risks and opportunities” so that market participants can assess whether these are aligned with the risks and opportunities that the company has identified as being material to its business. This also provides a basis upon which companies can be compared with a sector or industry.

There are three specific disclosures required:

(a) Disclose the metrics used by the organisation to assess climate-related risks and opportunities in line with its strategy and risk management process.

Metrics might cover climate-related risks associated with water, energy, land use, and waste management and, where climate-related issues are material, an explanation of how related performance metrics are incorporated into remuneration policies. Where relevant, a company should provide its internal carbon prices as well as climate-related opportunity metrics such as revenue from products and services designed for a lower-carbon economy. Metrics should be provided for historical periods to allow for trend analysis. In addition, where not apparent, the company should provide a description of the methodologies used to calculate or estimate climate-related metrics.

(b) Disclose Scope 1, Scope 2 and, if appropriate, Scope 3 greenhouse gas (GHG) emission and the related risks.

The company’s GHG emissions should be calculated in line with the ‘Greenhouse Gas Protocol’ methodology to allow for aggregation and comparability across organisations and jurisdictions and, if possible, related, generally accepted industryspecific GHG efficiency ratios should be provided. Under the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, Scope 1 emissions are direct emissions from owned or controlled sources. Scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions from the generation of electricity, steam, heating and cooling purchased by the company. Scope 3 emissions are all indirect emissions (not included in scope 2) that occur in the value chain of the reporting company, including both upstream and downstream emissions.

(c) Describe the targets used by the organisation to manage climate-related risks and opportunities and performance against target.

This should include the company’s key climate-related targets such as those related to GHG emissions, water usage, energy usage, etc., in line with anticipated regulatory requirements or market constraints or other goals. Such other goals may include efficiency or financial goals, financial loss tolerances, avoided GHG emissions through the entire product life cycle, or net revenue goals for products and services designed for a lower-carbon economy. In describing their targets, organisations should consider including the following:

‒ whether the target is absolute or intensity based,

‒ time frames over which the target applies,

‒ base year from which progress is measured, and

‒ key performance indicators used to assess progress against targets.

Where not apparent, organisations should provide a description of the methodologies used to calculate targets and measures.

Outlook

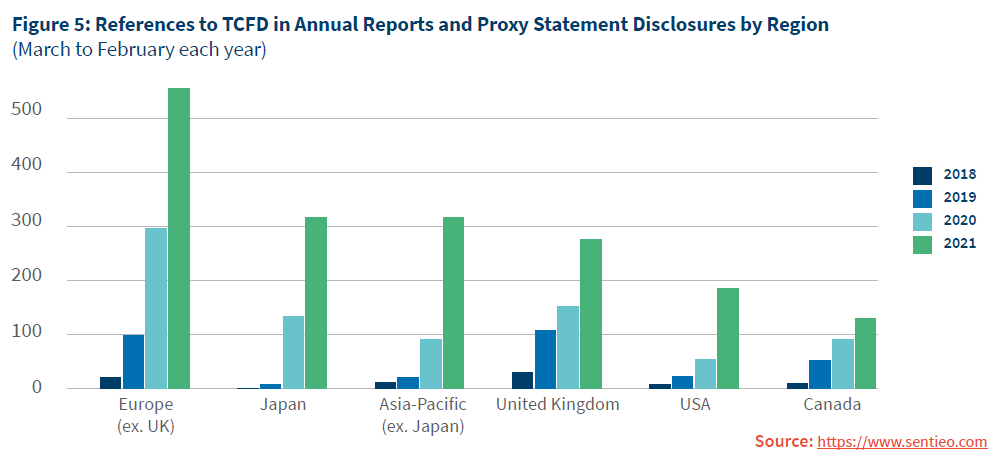

Across the globe, there is growing pressure on companies to enhance reporting on a range of ‘non-financial’ issues, in this instance climate change. The growth in references in company filings throughout the world so far in 2021 is just one example of that:

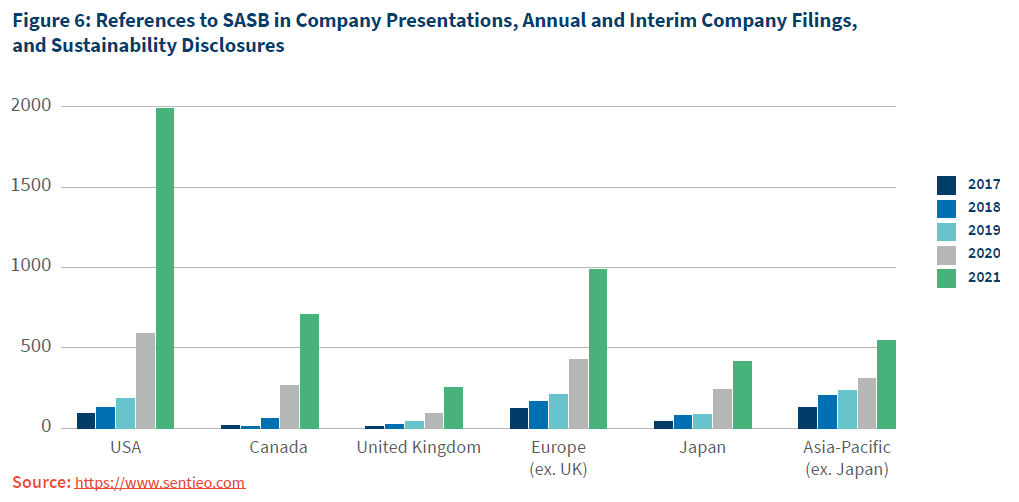

There is, however, some distance to travel in terms of reporting against the TCFD, let alone complete, material and meaningful disclosure of ESG or sustainability factors and indicators. The FRC has pointed to the combination of TCFD and SASB as representing a placeholder of sorts until more formal reporting standards are adopted. In addition to the growth in TCFD reporting, we are also seeing an increase in SASB reporting in the UK—albeit far below that of the US—the market for which SASB standards were designed.

Even in the UK, where both the market and the regulator have been at the forefront of strong disclosure for at least a decade, the variance in reporting is noteworthy, as are the relatively fleeting references to external disclosure frameworks. At best, this could by a symptom of a phased approach being taken by companies, gradually putting in place the strategies and governance frameworks that will produce a meaningful impact on internal decision-makers and, equally importantly, information for investors. At worst, it could be continued evidence of ‘box-ticking’, seeking to simply point to external frameworks to satisfy investors and claim that current approaches are sufficiently robust to meet those standards. The deluge of Annual Reports currently being released in advance of the 2021 AGM season, reporting on the 2020 financial year, will hold a clue. The 2022 AGM season, reporting on the 2021 financial year, may well definitively provide the answer. Soon after, UK companies—and those globally—may be facing shareholder votes on this matter on a regular basis.

Methodology

The data used in the paper is from regulatory filings (Annual Reports and Results Announcements) of UK companies between January 1st 2018 and December 31st 2020. While supplemental information has been included from documents outside of regulatory filings, without at least a reference of the TCFD in a regulatory filing, companies were not included. The rationale for this aligns with the approach of major frameworks such as SASB and TCFD, where most effective disclosure should be aligned with the standing of regulatory documents. For appropriate comparisons, companies without employees, such as real estate investment trusts and funds have not been included.

In terms of analysing disclosure of companies, given the absence of formal guidance from the TCFD as to what constitutes meeting the recommendations in full, the evaluation was conducted by multiple reviews from FTI Consulting.

| Type of Disclosure | Details |

|---|---|

| Reporting & Targets (most detailed) | Companies that provide extensive disclosure under each of the recommendations of the TCFD; set and monitor data; and, incorporate climate-related targets. |

| Reference & Targets | Companies that reference the TCFD and set climate-related targets without reporting extensively under its framework. |

| Reporting without Targets | Companies that provide extensive disclosure under each of the first three of the four pillar TCFD recommendations but have not established climate-related targets. |

| Reference or Commitment (least detailed) | Companies that merely refer to the TCFD framework or commit to disclosing against it in future years, as well as those that simply point to CDP and wider initiatives. |

Endnotes

1FCA introduces rule to enhance climate-related disclosures, available at: https://www.fca.org.uk/news/news-stories/fca-introduces-rule-enhance-climate-related-disclosures(go back)

2New Zealand becomes first to implement mandatory TCFD reporting, the CDSB, available at: https://www.cdsb.net/mandatory-reporting/1094/new-zealand-becomes-firstimplement-mandatory-tcfd-reporting(go back)

3Time to raise the bar on climate change reporting, The FRC, available at: https://www.frc.org.uk/news/november-2020/climate-pn(go back)

4Speech by Nikhil Rathi, CEO, at Green Horizon Summit: Rising to the Climate Challenge, available at: https://www.fca.org.uk/news/speeches/green-horizon-summit-risingclimate-challenge(go back)

5Time to raise the bar on climate change reporting, The FRC, available at: https://www.frc.org.uk/news/november-2020/climate-pn(go back)

62020 Status Report: Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, available at: https://www.fsb.org/2020/10/2020-status-report-task-force-on-climate-relatedfinancial-disclosures/(go back)

7The TCFD framework and recommendations are available in full at: https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2020/10/FINAL-2017-TCFD-Report-11052018.pdf(go back)

8TCFD Framework, available at: https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/about/(go back)

9Interim Report of the UK’s Joint Government Regulator TCFD Taskforce, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-joint-regulator-and-government-tcfdtaskforce-interim-report-and-roadmap(go back)

10Consultation on requiring mandatory climate-related financial disclosures by publicly quoted companies, large private companies and Limited Liability Partnerships (LLPs), Department of BEIS, available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/972422/Consultation_on_BEIS_ mandatory_climate-related_disclosure_requirements.pdf(go back)

11In its own Status Report, cited under reference six, the TCFD stated that “Asset manager and asset owner reporting to their clients and beneficiaries, respectively, is likely insufficient.” This report, however, focuses on reporting to investors and capital markets.(go back)

122020 Status Report: Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, available at: https://www.fsb.org/2020/10/2020-status-report-task-force-on-climate-relatedfinancial-disclosures/(go back)

13The TCFD framework and recommendations are available in full at: https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2020/10/FINAL-2017-TCFD-Report-11052018.pdf(go back)

Print

Print