Anuj A. Shah is Partner and Head of US & UK at KKS Advisors; Brian Tomlinson is Director of Research at the CEO Investor Forum, Chief Executives for Corporate Purpose (CECP); Emilie Kehl is Senior Associate and Lukas Rossi is an Associate at KKS Advisors. This post is based on their recent paper. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here); For Whom Corporate Leaders Bargain by Lucian A. Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel, and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here); Socially Responsible Firms by Alan Ferrell, Hao Liang, and Luc Renneboog (discussed on the Forum here); and Restoration: The Role Stakeholder Governance Must Play in Recreating a Fair and Sustainable American Economy—A Reply to Professor Rock by Leo E. Strine, Jr. (discussed on the Forum here).

Executive Summary

How much forward-looking information do public companies disclose, including on ESG themes? Do they provide targets and KPIs on themes key to long-term value creation? In this paper, we analyze the accessibility, quantity, and time frame of forward-looking information disclosed by the 25 constituents in the S&P 500 Pharmaceuticals, Biotechnology & Life Sciences GICS industry classifications.

Using an updated version of CECP’s Long-Term Plan (“LTP”) Framework, we assess four key disclosure channels (annual reports/10-K, stand-alone sustainability reports, proxy statements, and investor day transcripts) and find that forward-looking information is dispersed, and locating it is complex and time-consuming.

In addition, the amount of forward-looking disclosure varies across the LTP Framework’s nine themes, with the most found across the themes of Competitive Positioning and Trends. We find that near-term disclosures are most common.

We conclude with a practical set of executive-ready recommendations for corporate managers focused on setting targets, increasing transparency, refreshing materiality, and providing commentary on ESG disclosures.

Introduction

There are numerous benefits—from reducing costs to creating value—that may accrue to

a firm with a strong environmental, social, and governance (ESG) proposition. [1]

A growing and increasingly sophisticated class of ESG-focused investors is seeking specific information, in the form of company disclosures and narratives, that provides detailed insight into the composition of a firm’s ESG program and their commitment to embedding ESG into corporate strategy. Investors no longer see ESG as a niche strategy and not only require access to traditional financial metrics, but also to decision useful ESG information.

A key question then is whether firms provide investors with adequate transparency into their long-term plans and prospects (incorporating ESG), particularly given the numerous challenges that short-termism presents in capital markets. [2] Are firms systematically providing relevant information to investors to allow them to analyze the viability of long-term returns, i.e., to interrogate the sustainability of their business models?

This research project:

Our objective was to examine the time frame and quantity of long-term information in various reporting documents issued by the 25 constituents of the S&P 500 Pharmaceuticals, Biotechnology & Life Sciences GICS industry classifications. We focused our review on annual reports, proxy statements, investor day transcripts, and sustainability reports. The primary objective of our analysis was to observe 1) accessibility, 2) quantity, and 3) time frame of forward-looking information [3] disclosed by the firms. We aimed to uncover current disclosure practices and provide insights into the state of forward-looking information in terms of their clarity and usefulness. For our analysis, we re-purposed and updated the CEO Investor Forum’s Long-Term Plan Framework (LTP Framework) from our previous paper, “The Economic Significance of Long-Term Plans”. [4] Through this, we created a simple assessment methodology that is transparent, flexible, and scalable to other industries.

Why Biopharma?

Few industries have received more scrutiny and attention in the past year than Biopharma. It is an industry that has demonstrated an extraordinary capacity to both heal and harm. Most recently, we have felt a collective dependence on the Biopharma industry’s innovation infrastructure to rapidly develop and produce COVID-19 vaccines at scale. Contrastingly, the ongoing opioid crisis in the United States demonstrates the huge social and economic costs imposed when the industry, its advisors, and its distributors fail us. Through M&A activities, the industry has experienced consolidation, leaving a smaller group of larger, higher—profile companies that are readily exposed to scrutiny and reputational damage.

The effects of short-termism could be especially problematic in an industry where it may take 12—20 years of Research & Development (R&D) effort to progress from science ideation to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved product. [5] The mega-trends facing the industry, from demographic shifts to a changing climate, are also long-term in nature requiring adjustments in both technology and clinical capacity. There also exist broadly expressed concerns that industry consolidation, accompanied by share buy-back practices, may have abridged Biopharma’s overall R&D effort. [6]

R&D is the Biopharma industry’s main source of long-term value creation. The length and uncertainties of the product development life cycle should mean that, overall, the industry has a long-term outlook. Progressing through the phases of therapeutic development to FDA approval is also highly uncertain, with only a fraction of concepts making it to market. This necessarily means that Biopharma’s investor ecosystem ought to be set up for the long term, from Venture Capitalists (VCs) picking up early-stage research to institutional investors in mature, differentiated, listed Biopharma companies.

The centrality of R&D to valuation in Biopharma is demonstrated in market reactions to R&D-related announcements. Markets react significantly to news of particular therapeutics progressing through development phases. As one would expect, the largest price reactions tend to be in response to drug approval/rejection announcements. [7] These findings are also confirmed by sell-side analysts we spoke with who, simplifying significantly, are building models around the total addressable markets for current and prospective drugs.

ESG and Biopharma: Given even greater salience by COVID-19, Biopharma faces a unique set of ESG issues: pricing and access, product governance, and business ethics among them. Long-term we predict system-level issues like rising antimicrobial resistance will appear on institutional investors’ lists of high priority engagement topics; this ties further into broader public policy concerns of structural under-investment in antibiotic development. Human capital continues to be a material issue across sectors. Biopharma companies are expected to have a clear story on the attraction and retention of specialist talent; providing personal development opportunities, compelling projects, and disseminating a strong sense of corporate purpose to their highly educated and sought-after workforce is a must. It is also expected that the industry sets targets for diversity and inclusion and meets heightened disclosure expectations, such as the public disclosure of workforce composition data (for example, as set out in Form EEO-1, which has been the subject of several investor engagement efforts).

It is also worth highlighting that the industry’s significant exposure to litigation risk and high intensity regulatory oversight is tied to material ESG issues (i.e., issues likely to affect the operating performance or financial condition of a business) for the industry (such as drug pricing and business ethics).

We acknowledge that companies in the Biopharma industry are actively working to enhance their ESG stance (both in disclosure and practice). Building on that work, in a recent report titled “Integrating Sustainability for the Biopharma Sector”, [8] CECP’s CEO Investor Forum and the Biopharma Sustainability Roundtable issued guidance for the industry on how to better communicate ESG risks and opportunities and a longer-term outlook. This builds on the CEO Investor Forum’s work across research, frameworks, and investor-facing conferences, to provide guidance and a forum to enable CEOs to talk to the capital markets about a long-term time horizon.

More Forward-looking ESG: The view from Biopharma Analysts

We spoke to both buy-side and sell-side Biopharma analysts on general themes that speak to issues of relevance for this paper. Below is an aggregated summary of their feedback.

ESG: As a broad class of themes, ESG is seen to be growing in importance. Several of the buy-side analysts we spoke with expected to see target-setting from firms to better enable progress tracking and an assessment of the focus and value-relevance of ESG-related initiatives. Sell-side analysts noted that the interaction of price and access was an area where ESG issues became much more relevant to a valuation analysis. Many “ESG issues” were, of course, not new issues for the industry or analysts. However, the ESG lens had expanded the manner in which these themes were assessed; for example, the equity element of price coming in for closer analysis.

Some areas that had been a focus for ESG disclosures seemed to be a relatively low priority. For example, some analysts saw that the value of creating a Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) report was, in many ways, to show that climate was not a highly material issue for the company. Consequently, it would not be a meaningful feature of analyst assessments for these companies. Nonetheless, given that climate was a system-level issue, the expectation was clear: companies needed to demonstrate awareness and capability on the theme of climate and should use the available reporting infrastructure (TCFD) to do so.

Human capital—encompassing both intellectual and relationship capital—was a key consideration. R&D—the industry’s primary source of long-term value creation—is fundamentally a people-centric activity. Several analysts noted that there was still work to be done on connecting culture and purpose to the core Biopharma function of R&D. Of course, understanding R&D effectiveness is critical for analysts, i.e., how successful a company is at converting clinical assets into products.

Several analysts noted that ESG is still often thought of and engaged with through a scandal and controversy lens. This is often reflected in the way ESG is dealt with in rating taxonomies, which pick up issues that generate public attention (such as pricing and selling practices) that can result in litigation, Department of Justice or FDA involvement, and/or garner significant press attention.

Forums and guidance: Investor/capital markets days were generally highlighted as critical forums for sharing a long-term outlook. In any industry, any form of truly long-term guidance is laced with uncertainty; that is particularly so in Biopharma where long-term prospects rely on progressing through drug development phases and, ultimately, achieving regulatory clearance. Some frustration was expressed by the analysts with regards to generic disclosure documents, like annual reports, which are viewed as having a bit too much “fluff” and “don’t add much to the valuation picture”.

Of course, forward-guidance practices vary widely across the industry and are driven particularly by the respective development stage of potential clinical assets. Nonetheless, providing a long-term time horizon was important, particularly to providing insights around how performance interacts with patent expiration timelines. Several analysts noted that much of the industry could provide some level of strategic insight out to five years.

Of course, the further into the future you are seeking to disclose, the more probabilistic disclosure becomes. That makes such insights hard to provide but highly valuable. Overall, analysts place a high value on long-term guidance in various forms but are realistic about the challenges of issuing such guidance. Long-term guidance is often taken with a pinch of salt—with analysts fully aware of the very real concerns management has of giving guidance that they then may regret.

Research Approach: Assessing against the CECP Long-Term Plan Framework

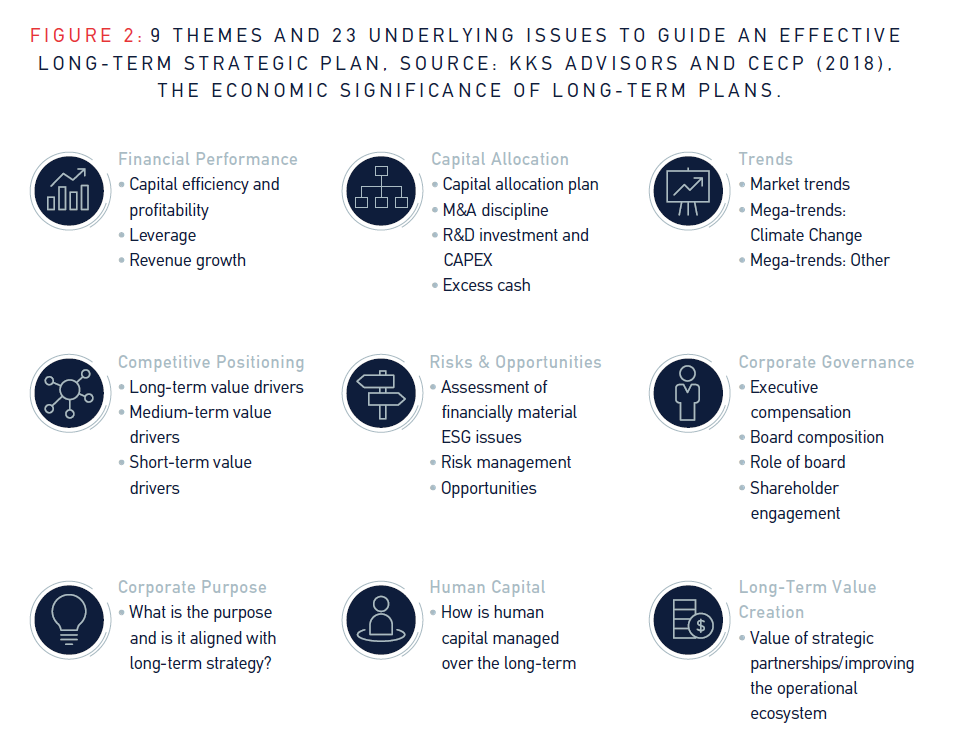

To evaluate and quantify the Biopharma sector’s forward-looking disclosures in a systematic way, we used an updated version of the CECP Long-Term Plan Framework (“LTP Framework”) from our 2018 whitepaper “The Economic Significance of Long-Term Plans”. The framework provides companies with a set of nine themes designed to effectively communicate the critical elements of a long-term strategic plan and respond to the informational needs of institutional investors.

We made a small change to the framework by adding “Mega-trends: Climate Change” as a separate issue under the broader “Trends” theme. We did this to enable more granularity across non-climate “Trends”, given the volume of climate-related disclosure we found. In summary, the revised framework has a set of 23 issues across 9 themes and one new subdivision (see Figure 2).

Research Sample:

For our analysis, we focused on the 25 constituents in the S&P 500 Pharmaceuticals, Biotechnology & Life Sciences GICS industry. We selected fiscal year 2019 as the year of analysis for two main reasons: 1) data for this research study was collected in the first quarter of 2021. In many cases, sample companies had not yet made key disclosure documents (i.e., sustainability reports) available to the public for 2020; 2) 2019 represented a more ‘business as usual’ period given the extraordinary business circumstances the global pandemic presented for much of 2020. Since companies tend to hold investor days every other year, we expanded the time horizon of assessed investor days to include the years 2018 through 2020; given the role of the investor day in providing long-term guidance we also did not want to omit it from our analysis.

Our data collection process focused on four key disclosure channels:

- Annual Reports/10-K,

- Stand alone Sustainability Reports,

- Proxy Statements, and

- Investor Day Transcripts.

Among the assessed companies, 23 or 92% published a sustainability report for 2019 (in line with the proportion of S&P500 companies that issue sustainability reports).

Less than half of the sample (44%) held an Investor Day for which transcripts are publicly accessible.

Scoring:

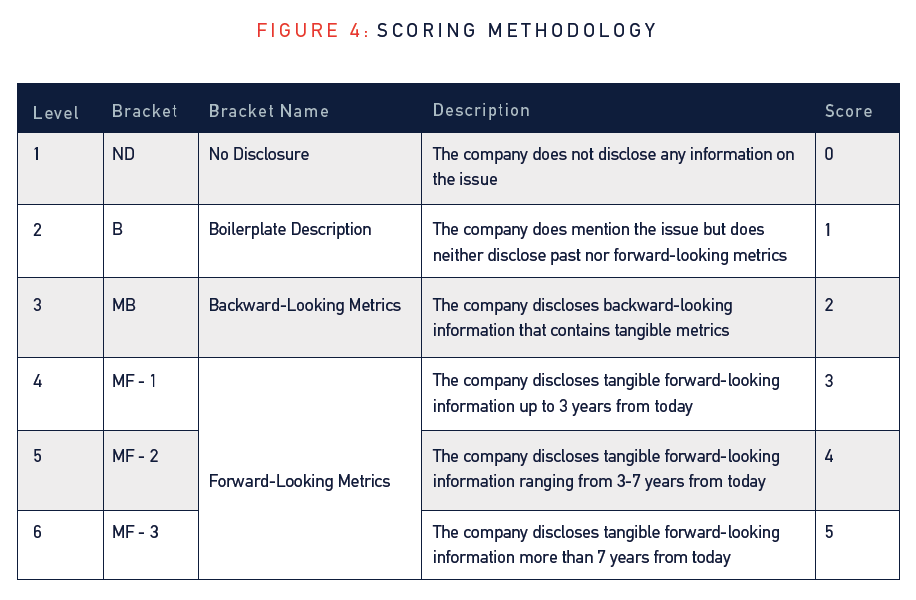

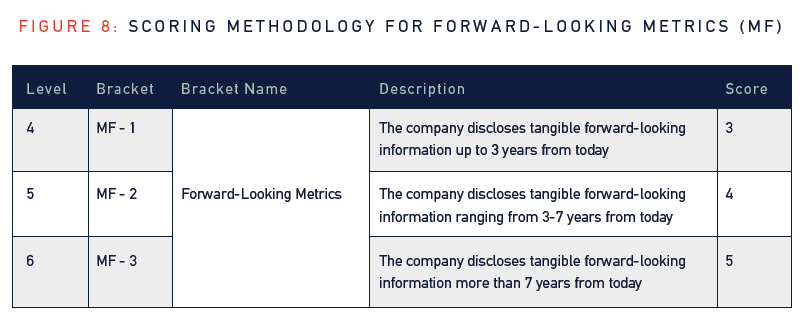

To evaluate the disclosures against the adjusted LTP Framework, we created and applied a scoring system (see table below). This scoring system was split into 4 levels (i.e., no disclosure, boilerplate description, backward-looking metrics, forward-looking metrics.

However, in contrast to our previous scoring framework, we allowed for more granular scoring by introducing 3 additional layers in the forward-looking bracket (i.e., MF-1, MF-2, MF-3). This enabled us to not only assess the quantity of forward-looking metrics, but to also distinguish between timeframes addressed. We split the forward-looking bracket at 3+ and 7+ year intervals as a compromise between structurally different themes and issues (i.e., those more prone to short-term disclosures such as issues in the “Financial Performance” theme vs. issues in the “Trends” theme that tend to be more long-term oriented). Each level is linked to a number score that allowed us to rank and compare the information disclosed by our 25 sample companies. For each of the 23 issues in the adjusted LTP framework, we focused on the “highest attained level” of company disclosure. The purpose of the scoring analysis was not to gather a representative disclosure analysis, but to identify and reward the best disclosure we found in each category (i.e., the most forward-looking / specific statement).

Example of the disclosure assessment workflow by theme:

- Assess Company X’s disclosure on the issue “Mega-trends: Climate Change” within theme

“Trends” - Find a statement claiming that the company has reduced global carbon emissions by 40% over the past five years; this disclosure is first awarded with MB (Backward-Looking Metrics)

- Further review the disclosures and, in a different location, find a section on the firm’s plans to

reduce absolute global emissions by a further 30% by 2025; this disclosure is then awarded with MF-2 (Forward-Looking Metrics with a 3—7 year time horizon) - If we identify a MF-3 disclosure, we do not seek additional disclosures that could be categorized as MF-2, MF-1, MB, or B

Disclosure assessment workflow

Data Collection Issues (disclaimer):

We applied a thorough data collection approach involving multiple researchers and data checking

mechanisms. While the total page count of information assessed exceeded 7,000 pages, we tracked each information point and applied peer review to minimize data collection issues. However, there are inherent challenges presented by attempting to manually capture all relevant forward-looking information; unsystematic and diffuse disclosure presents stakeholders with accessibility and analysis issues.

Findings: The State of Forward-looking Disclosures

As mentioned in the previous section, the objective of this research was to assess the 1) accessibility, 2) quantity, and 3) time frame of forward-looking information. We aimed to uncover current disclosure practices and provide insights into the state of forward-looking information, in terms of their clarity and usefulness, by focusing on “representative” rather than “comprehensive” disclosures by each theme. Our scoring methodology then sought to reward “the best” disclosures (i.e., by metrics and time-horizon).

Accessibility: Hunting for Forward-Looking Disclosures

We have previously encountered the challenge of reaching a developed understanding of a company’s long-term strategic outlook and prospects. In a prior paper, we found that a review of more than ten disclosure formats was required to form a picture, across key themes, of a long-term outlook; the information provided often being at only a boilerplate level of detail. [9] As expected, we found that there is no “one-stop-shop” for disclosure materials; these were dispersed across the reviewed disclosures (i.e., Annual Reports/10-K, Proxy Statements, Sustainability Reports, Investor Day Transcripts). To assess just 25 companies, we reviewed more than 7,000 pages of corporate disclosures. On average, that is 300 pages across the four disclosure forums per company.

A primary objective of corporate reporting is to not bury investors under an “avalanche of trivial information”. Nonetheless, the significant expansion we have seen in the reporting ecosystem is welcome overall as it represents an effort to communicate to capital markets and stakeholders across a broader set of themes than conventional financial reporting. Nonetheless, it can make locating information complex and time-consuming.

Quantity overall:

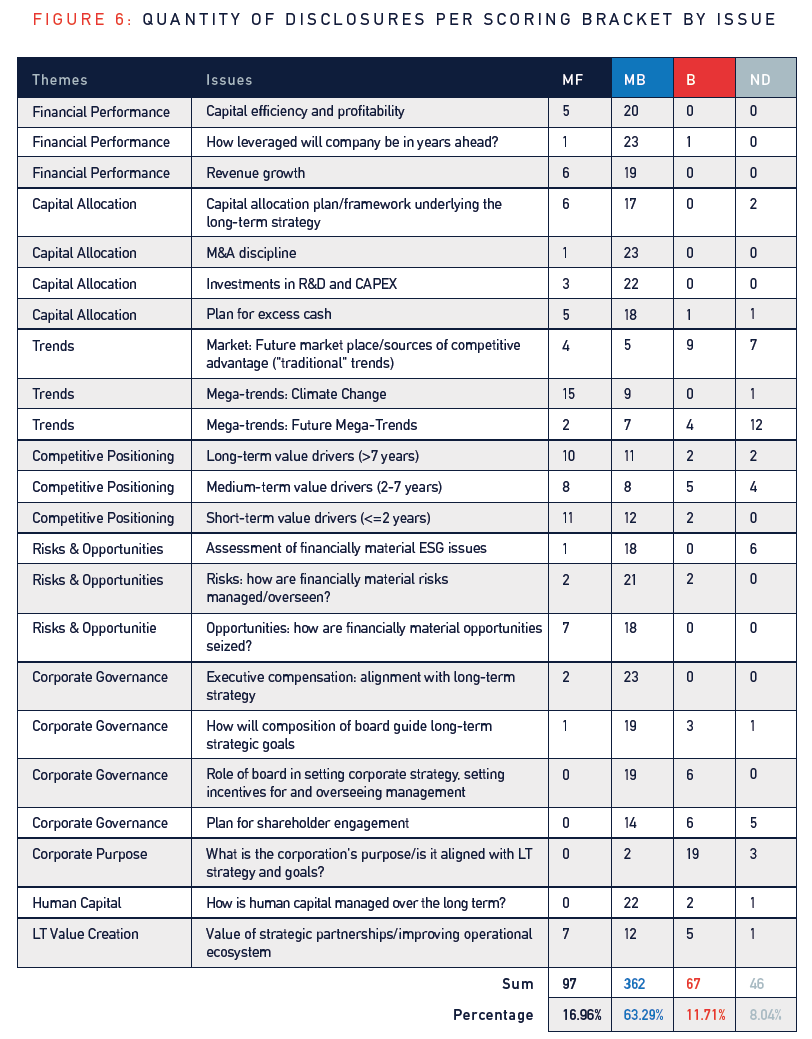

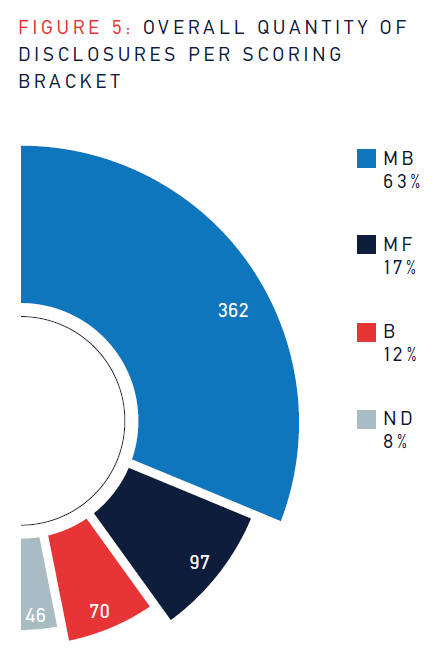

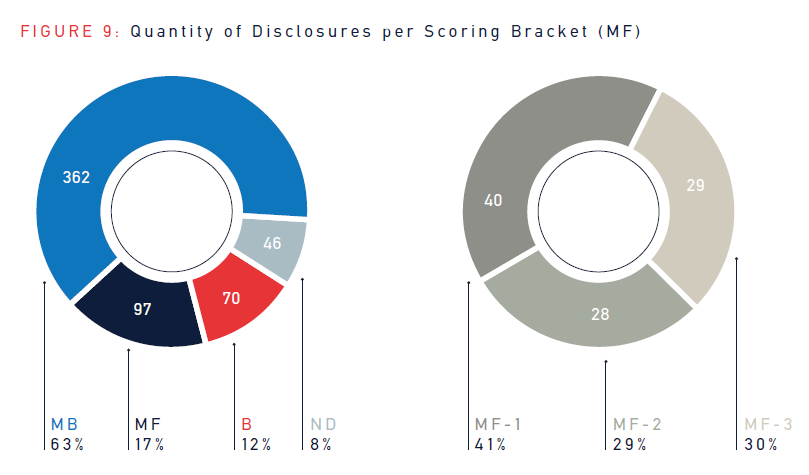

In total, we collected 575 datapoints for the 25 companies and 23 issues included in the LTP Framework. As shown in the graph, nearly 2/3rds of the datapoints are backward-looking (MB). In contrast, forward-looking statements (MF) account for only 17% of disclosures collected. 70 datapoints (approximately 12% of disclosures) were identified as boilerplate information. In those cases, the company referenced an issue included in the LTP Framework (e.g., Corporate Purpose) but neither disclosed forward- or backward-looking metrics.

Quantity per theme:

As you would expect, the amount of forward-looking disclosure varies across the LTP Framework’s 9 themes: some are intrinsically forward-looking (trends), others involve more complex work to provide targets, and still others where target-setting is expected to become standard, but we are not there yet (e.g., certain topics in the S of the ESG spectrum). The table below depicts the final distribution of disclosures:

On a theme level, we find that companies most often disclosed the most forward-looking information on: “Competitive Positioning” (29 datapoints across 3 issues) and “Trends” (21 datapoints across 3 issues), with the issue of “Mega-trends: Climate Change” dominating by far (15 datapoints). On the flipside, on some themes, forward disclosure appears largely absent, such as in “Human Capital”.

Spotlight—Competitive Positioning:

As expected, given the nature of the Biopharma industry, companies disclose significant volumes of forward-looking metrics on their competitive positioning. The issues in our framework focus on value drivers and how actions are linked to key milestones and goals. The value drivers are broken down further to include long-term value drivers (more than 7 years’ time horizon, relating to strategic health), medium-term value drivers (between 2-7 years’ time horizon, relating to commercial/cost structure and asset health), and short-term value drivers (less than 2 years’ time horizon, relating to sales, operating cost, or capital productivity).

- Example Disclosure 1: “We are confident that our current and emerging portfolio of medicines matches up well with the needs of patients in the Asia-Pacific region–so much so that we expect roughly 25% of our total sales growth to come from this region over the next 10 years”

(Forward-Looking Metric, Competitive Positioning: Capital Allocation: Long-term value drivers (>7 years), Source: Annual Report) - Example Disclosure 2: “We expect to realize $2.5 billion of synergies resulting from cost savings and avoidance through 2022 and our integration efforts across general and administrative, manufacturing, R&D, procurement and streamlining the Company’s pricing and information technology infrastructure” (Forward-Looking Metric, Competitive Positioning:

Capital Allocation: Medium-term value drivers (2-7 Years), Source: Annual Report)

Spotlight—Trends:

Our “Trends” theme covers disclosures that are split into “market trends” and “mega-trends”. The market trends involve projections of the future marketplace and sources of competitive advantage in the new marketplace (so-called “traditional” trends). Mega-trends are those affecting people and operations and may not be industry-specific in scope. We assess disclosures on climate change-related risks and opportunities separately from disclosures on other mega-trends (e.g., automation).

Given the current widely acknowledged urgency for companies to act on climate change, it comes as no surprise that this issue—with 15 MF disclosures—provides the single most forward-looking statements. Climate-related disclosures require a mix of short-term, medium-term, and long-term disclosures to meaningfully outline strategy and impacts and meet investor expectations; this is assisted by the availability of supportive reporting infrastructure (TCFD). Though climate change is systemically urgent, we also note that it may not currently be regarded as a highly material issue for Biopharma companies themselves (particularly when compared to other sectors such as oil and gas).

Other ESG issues are found to be of greater significance for investors assessing operational performance and financial prospects, an outlook confirmed by the analysts we spoke with.

- Example Disclosure 1: “[Company name] recognizes the potential impacts associated with climate change and the risks of severe weather events. We set aggressive targets for improving energy efficiency and, as a result, reducing our greenhouse gas emissions intensity […] 2020 Environmental Goals: Reduce GHG by 20%, Waste Efficiency: 20%” (Forward-Looking Metrics, Trends: Mega-trends: Climate Change, Source: Sustainability Report)

- Example Disclosure 2: “We have a goal to reduce our greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions by 30% by 2025, from a 2016 baseline. We have already cut GHG emissions by 9%” (Forward-Looking Metrics, Trends: Mega-trends: Climate Change, Source: Proxy Statement)

In our view, a limited number of firms report meaningful future-oriented information on other mega-trends in the disclosure documents we examined; though of course, these companies provide significant quantities of backward-looking or boilerplate information in relation to this theme (such as those set out in Risk Factor disclosures). Additionally, some mega-trend-type content is, to some extent, addressed in the projections of competitive positioning.

- Example Disclosure: “Data science is a driver of astonishing health technology innovation today, and we are at an inflection point where health, technology and consumer industries are converging in new ways. Across the Company, we are employing leading-edge analytical tools, including machine learning, deep learning, natural language processing, and more to analyse new and expanded sources of data.” (Backward-Looking Metric, Trends: Future Mega-trends, Source: Sustainability Report)

Spotlight—Human Capital:

Investors are increasingly focusing on understanding how a company currently manages its human capital and how it seeks to address potential future shortcomings; a trend reflected in the SEC’s recent adjustments to reporting human capital issues in Regulation S-K. This is driven by many factors, including evidence that talent attraction and retention play an important role in the long-term success and continuity of a business. There are also expanded expectations of diversity and inclusion practices, with investors expecting data to understand workforce composition (for example, through public disclosure of EEO-1 data).

Yet, in this analysis we find that forward-looking human capital targets are largely absent in the examined disclosures. However, we acknowledge that our research focuses on data from 2019 and that the increased focus on social issues in 2020 may have already increased the amount of reporting on forward-looking human capital management disclosures. As such, progress is reported, but we find limited to no target setting.

- Example Disclosure 1: “From the end of 2015 to the end of 2019, we increased the number of women in management globally from 41% to 45%. For racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S., we increased management representation from 18% to 24% of total management. (Backward-Looking Metric, Human Capital, Source: Sustainability Report)

- Example Disclosure 2: “[Company name] is focused on having a pipeline of talent advancing through our organization and on providing opportunities for all employees to develop within a role as well as toward their next role. We will continue to consider a diverse slate of candidates for progression through our succession planning process. (Boilerplate Description, Human Capital, Source: Sustainability Report)

Spotlight—Corporate Purpose:

Now more than ever, employees seek to work for companies with a clear purpose. Most companies included in our research sample were found to communicate a purpose statement. However, when assessing whether the firm’s purpose is aligned with long-term strategy and goals, we predominately identified boilerplate disclosure (80%). As the purpose statements suggest, Biopharma companies do not intrinsically “have a purpose problem”. Purpose is built into most business models; the discovery of therapeutic solutions to problems presented by human health. We of course see Biopharma companies that largely pursue M&A strategies, rather than developing solutions, and companies that have used practices regarded as unethical in terms of drug pricing and drug distribution. We do, however, think that more companies can connect to “purpose” more clearly via the technical aspects of their core work of developing therapies and treatments. For example, how does purpose connect with the R&D pipeline and the decision-matrix for what gets funded and what does not. This is also an emerging expectation among some analysts.

- Example Disclosure 1: “Our purpose is to unite caring with discovery to create medicines that make life better for people around the world.” (Boilerplate Disclosure, Corporate Purpose,

Source: Annual Report & Proxy Statement) - Example Disclosure 2: “At [company name], our passion for our Mission is what inspires us to succeed. We can’t think of a better purpose than to use our talent and expertise to enable our customers to make the world healthier, cleaner and safer for future generations. The past 10 years have been incredible. But knowing how quickly science continues to evolve, I know that our achievements will be even greater as we set our sights on 2030.” (Boilerplate Disclosure, Corporate Purpose, Source: Annual Report)

Spotlight—Firm Focus on ESG:

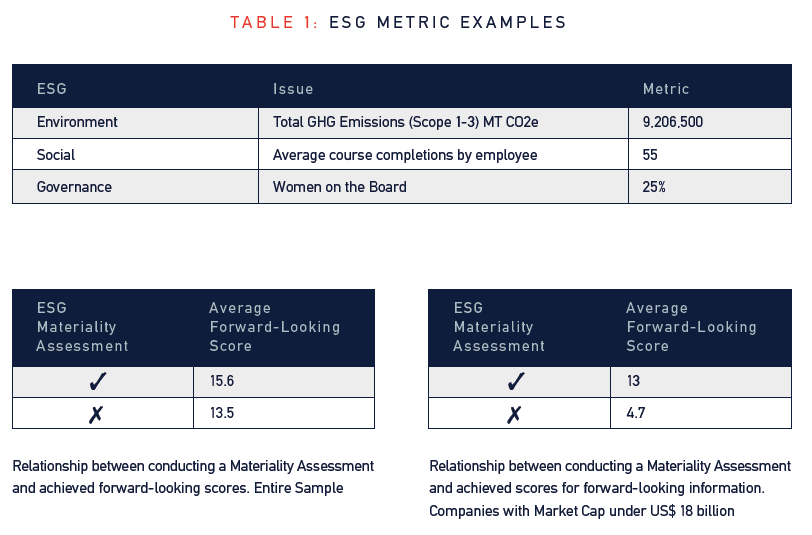

There is a maturity curve for corporations developing ESG awareness and practice. We have addressed that in prior work, but it requires cross-functional collaboration, information sharing, and reaching shared understanding on new and emerging themes. [10] A key element in that development is often conducting a materiality or priority issue assessment. Under the “Risk and Opportunities” theme we verified whether companies conducted a materiality assessment and subsequently analyzed the impact of such an assessment within our research.

According to our review, close to 75% of the analyzed companies completed a materiality assessment. Companies without a materiality assessment, on average, provide less forward-looking disclosure and hence achieved a lower disclosure score. This pattern is especially clear among smaller companies in the sample. Those that conducted a materiality assessment achieved significantly higher disclosure scores than those that have not conducted a materiality assessment.

- Example Disclosure 1: “In 2018, we laid the groundwork to begin our Materiality Assessment, completing the process in 2019. These results will continue to inform our evolving sustainability strategy and our business planning until our next Materiality Assessment in 2021. (Forward-Looking Metric, Assessment of financially material ESG issues, Source: Sustainability Report)

Quantity by size of company:

Establishing comprehensive, forward-looking targets is not a straightforward task, and the type of disclosure that can be provided is theme dependent; to provide reliable and actionable insights, a company must make substantial operational investments. Based on these associated costs, we would expect bigger and more resourced firms to perform better in our analysis. However, our data showed only a medium correlation between market cap and disclosure.

We also observed an uptick in forward-looking information for the smallest companies in our sample, suggesting that those companies do recognize the benefits of committing to providing long-term information. It is also possible that smaller firms see a long-term orientation as a potential source of competitive advantage and a strategic way to attract long-term focused investors. In prior work, we described how companies can use their disclosure stance to adjust the composition of their investor base. It may also be that smaller firms, more reliant on future approvals, need to put more work into explaining their forward value proposition given its inherent risks and uncertainties.

Time frame

We also sought to assess the time frame of forward-looking disclosures in a scalable, comparable way. We implemented more granular scoring by introducing 3 additional layers in the forward-looking bracket, namely: less than 3 years; 3 to 7 years; and 7 years and beyond.

Our results reflect and reinforce the inherent challenges companies face when considering long-term guidance across a range of themes. By further breaking down the 97 datapoints we identified as Forward-Looking Metrics (MF), we found that: the short-term bracket (next three years) contains the most forward-looking disclosures (40%). Both mid-term and long-term brackets, 3-7 and above 7 years respectively, contain close to 30% of the disclosures. We acknowledge again the complexity involved in providing truly long-term guidance and targets; the longer the time horizon a disclosure addresses the more probabilistic the disclosure is likely to become. Such long-term disclosures are also likely to be more strategic and high-level rather than seeking to provide metrics, depending on the theme addressed (for targets on GHG reduction are now expected).

Example disclosures for each time horizon:

- Example Disclosure 1: “Starting in 2020, we will provide patients in China with affordable access to key treatments for hepatitis B, HCV and HIV” (Forward-Looking Metrics, Time Horizon: <3 years, Risks & Opportunities: Opportunities, Source: Sustainability Report)

- Example Disclosure 2: “The [company name] also estimates that approximately 270 new molecular entities (“NMEs”) are expected to be approved between 2021 and 2025” (Forward-Looking Metrics, Time Horizon: 3-7 years, Risks & Opportunities: Opportunities, Source: Form 10-K)

- Example Disclosure 3: “In 2019, [company name] publicly committed to invest more than $500 million over the next four years in discovery, development and delivery programs to advance the global effort to eliminate HIV and TB by 2030. HIV and TB are two of the world’s deadliest diseases, together claiming more than two million lives every year, primarily in resource-limited settings” (Forward-Looking Metrics, Time Horizon: >7 years, Risks & Opportunities: Opportunities, Source: Sustainability Report)

Recommendations:

Building on our work over the last several years and the findings of this report, we set out the following recommendations for corporate managers:

- Set targets: Companies should set targets (including on ESG). The targets they set should be in relation to material issues for the business—or in response to broad-based expectations from institutional investors and civil society.

- Disclose process: Companies should identify their basis for target setting. Where do the goals come from and why were they set? Targets are not in themselves good, particularly if they relate to irrelevant or immaterial themes. As such, companies can provide context and commentary about how targets connect to financial outcomes and why targets were set at particular thresholds.

- Prospective materiality/regular refresh: The relevance of issues evolves over time. Issues that are not material today may become so. Companies can talk about how they engage with this. Two examples: (1) outline the process and periodicity to re-visit and refresh the materiality or priority issue assessment; (2) provide ongoing, non-boilerplate, commentary on mega-trends

and how these connect to strategic opportunities. - Focus disclosure: It should not be too hard and/or time-consuming to build an integrated picture, incorporating ESG themes, of a company’s forward story. After all, an objective of securities laws is not to bury investors under an avalanche of trivial information. Given the expansion of the reporting ecosystem, companies should ease the analytical burden on the consumers of the information disclosed by taking the time to identify those disclosures that they consider the most material and explain why.

- ESG maturity curve: There is a maturity curve for engaging with and disclosing ESG issues. Companies should demonstrate candor about the development of their approach to different elements of the ESG issue spectrum and communicate progress (i.e., what we have done so far and how our stance will evolve). For example, this can be done by referencing the sequence of engagement with different reporting frameworks, whether company-wide (e.g., SASB) or on specific themes (e.g., EEO-1 disclosure). Additionally, companies can begin with output metrics and over time progress to outcomes and impacts.

Reports related to recommendations:

- ESG and the Earnings Call

- The Return on Purpose

- Method of Production of Long-Term Plans

- Emerging Practice in Long-Term Plans

- ExxonMobil: Constructing a Mock Long-Term Plan

Plus, related recommendations from the Biopharma Sustainability Roundtable:

Plus, related recommendations from FCLTGlobal:

The complete paper is available for download here.

Endnotes

1Whelan et al., ESG and ESG AND FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE: Uncovering the Relationship by Aggregating Evidence from 1,000 Plus Studies Published between 2015—2020,

https://www.stern.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/assets/documents/NYU-RAM_ESG-Paper_2021%20Rev_0.pdf(go back)

2Eckerle, Kevin and Tomlinson, Brian and Whelan, Tensie, ESG and the Earnings Call: Communicating Sustainable Value Creation Quarter by Quarter (May 27, 2020). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3607921(go back)

3Securities laws in the United States provide a broad safe harbor for public companies making forward-looking statements. The SEC, in April 2020, also reiterated the importance of public companies providing robust forward-looking information: https://www.sec.gov/news/public-statement/statement-clayton-hinman(go back)

4KKS Advisors and CECP (2018), The Economic Significance of Long-Term Plans,

https://www.kksadvisors.com/the-economic-significance-of-long-term-plans(go back)

5Krieger, Joshua and Li, Danielle and Papanikolaou, Dimitris, Missing Novelty in Drug Development (May 2018). NBER Working Paper No. w24595, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3177954(go back)

6Biopharmaceutical Industry Consolidation Diminishes Future Drug Discovery by John LaMattina (2014): https://www.forbes.com/sites/-johnlamattina/2014/06/10/biopharmaceutical-industry-consolidation-diminishes-future-drug-discovery/?sh=381eddd12c9b; Killer Profits by Rep Katie Porter (2020): https://porter.house.gov/uploadedfiles/final_pharma_ma_and_innovation_report_january_2021.pdf;

Keum, Daniel, Innovation, Short-termism, and the Cost of Strong Corporate Governance (January 1, 2018). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3634364 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3634364(go back)

7Tomovic and Atukeren (2010), Long-term value creation in the pharmaceutical sector: an event study analysis of big pharma stocks, http://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJSE.2012.049609(go back)

8Integrating Sustainability and Long Term Planning for the Biopharma Sector by Myrto Kontaxi (Biopharma Sustainability Roundtable) and Brian Tomlinson (Chief Executives for Corporate Purpose): https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2021/04/17/integrating-sustainability-

and-long-term-planning-for-the-biopharma-sector(go back)

9Krzus, Michael P. and Tomlinson, Brian, ExxonMobil: Constructing a Mock Long-Term Plan (March 23, 2019). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3359658(go back)

10Tomlinson, Brian and Krzus, Michael P., Method of Production of Long-Term Plans (January 25, 2019). CECP: Strategic Investor Initiative White Paper No. 3, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3332342 (go back)

Print

Print