Matt Leatherman is Director, Ariel Babcock is Head of Research, and Victoria Tellez is Senior Research Associate at FCLTGlobal. This post is based on a FCLTGlobal memorandum by Mr. Leatherman, Ms. Babcock, Ms. Tellez, and Sam Sterling. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, and Wei Jiang (discussed on the Forum here); and Who Bleeds When the Wolves Bite? A Flesh-and-Blood Perspective on Hedge Fund Activism and Our Strange Corporate Governance System by Leo E. Strine, Jr. (discussed on the Forum here).

Investment organizations around the world face an array of ever-changing external expectations. These expectations go well beyond traditional notions of achieving return targets or liability matching and can create important responsibilities that are broader than fiduciary duty or asset stewardship. Ripples of Responsibility provides tools for understanding and fulfilling these responsibilities. Together with our members and others, we have piloted this publication’s toolkit in workshops focused on six different domains of responsibility: economic impact at home and abroad, equity lending and stewardship, impasses in corporate engagement, racial and gender diversity of portfolio companies, climate and environmental impact, and reputation management.

The way that investment organizations navigate existing responsibilities and new expectations that arise has a tremendous effect on their long-term success.

When an investment organization fails to fulfill true responsibilities, staff can become distracted from their long-term focus, interrupting the organization’s long-term investment strategy. Consequences also can include turnover in leadership or responses by legal or regulatory authorities that narrow the discretion of leadership. Yet positive cases of investment organizations meeting evolving expectations abound: two examples are Future Fund’s efforts to ensure that external managers steward its reputation appropriately and the New Zealand Super Fund’s participation in the national response to social media firms live streaming the Christchurch atrocity. [1] [2]

Fundamentally, evolving expectations extend beyond what returns investment organizations earn to how they earn those returns.

Determining which expectations to accept as responsibilities is based on the long-term purpose of the organization, its constituents, and the trade-offs that accepting a particular responsibility would entail. Some—but not all—of these evolving expectations become true responsibilities, and investment organizations must make such determinations on a case-by-case basis. Making these judgments and managing responsibilities is a complex challenge, not amenable to a checklist.

Investment culture often involves solving problems and moving on, prioritizing numerical answers, and observing rather than creating markets. It can be tempting to try simplifying complex problems like responsibility into checklists—trading rules, exclusion flags, compliance reports. In truth, though, ongoing interaction and feedback are central to managing the complexity of investor responsibilities with inherent trade-offs and judgments.

Still, the process for making these decisions can be more standard. Keeping an inventory of existing responsibilities and anticipating potential new ones is part of the job for long-term investment organizations. Long-term funds also must fulfill their responsibilities reliably throughout their often large and complex organizations and communicate those responsibilities to a wide range of audiences, including the general public. Ripples of Responsibility provides a crisp way for investment organizations to understand the sometimes-abstract concepts of responsibility and offers a practical toolkit to help identify existing responsibilities, anticipate new ones, fulfill them, and communicate accordingly.

Understanding Investor Responsibilities

Expectations of long-term investors have expanded well beyond usual notions of their core purpose to include their broader impact on markets, society, and the environment. [3]

The fact that investors have broader responsibilities is clear. Defining those responsibilities is not. Investors need a common way to identify, anticipate, and communicate responsibilities before they can aspire to fulfill them across their organizations.

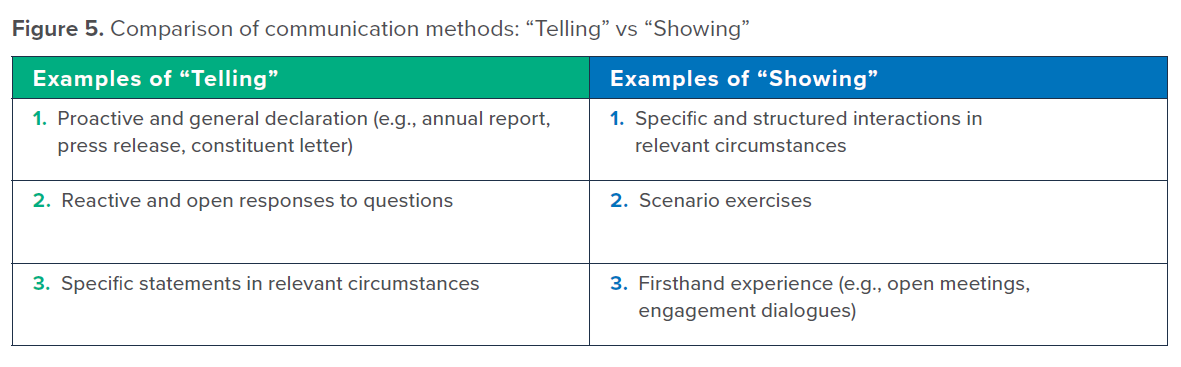

One way to think about investor responsibility is to compare it to a rippling pond. Expectations come from constituents standing on the shoreline tossing stones into the pond. The way that investors navigate these “ripples” of responsibility has a tremendous effect on their long-term success.

Long-term focus includes earning target returns through responsible behavior that creates opportunity. Neglecting responsibilities risks being forced into survival mode, with staff becoming distracted, strategy being interrupted, and leaders turning over. Neglecting responsibilities also could result in a response by legal or regulatory authorities, limiting investment organizations’ decision-making ability. [4]

Responsible behavior by an investor is necessary to focus on the long term. That behavior alone is not sufficient—returns still have to be earned and purposes fulfilled—but lack of clarity on responsibilities will inevitably detract from an investor’s long-term focus, jeopardizing the organization’s license to operate.

Managing these responsibilities is a complex challenge that is not amenable to a checklist. Complexity is uncomfortable for many investors. Investment culture often involves solving problems and moving on, prioritizing numerical answers, and observing rather than creating markets. It can be tempting to try to simplify the complex problems that responsibilities represent into checklists—trading rules, exclusion flags, compliance reports. Or it can be easy to dismiss a potential responsibility based on the source of the initial expectation. In contrast, ongoing interaction and feedback are central to managing the complexity of investor responsibilities with its inherent trade-offs and judgments.

In this post, our goal is to share research and provide tools that enable investment organizations to:

- Identify their core responsibilities,

- Determine how expectations become responsibilities, and

- Consider the steps necessary for the fund to meet those responsibilities.

Consequences

The consequences of an investment organization fulfilling—or not fulfilling—its responsibilities ripple widely.

Ongoing, short-term financial return is the narrowest consequence (as shown in Figure 1). Responsibility ripples outward from there to the organization’s long-term, cumulative return. Yet importantly, the rippling extends well beyond the return that an investment organization earns.

Institutional investors change their dimensions for measuring performance when they accept a new or evolved responsibility. The effect of accepting a responsibility can be to limit the investable universe, control externalities, require durability of performance over certain time horizons, or any combination of these standards.

Limiting the investable universe means narrowing the opportunity set from which investment organizations can build portfolios. The impact of such limits can range widely from potentially helping to add value to constraining investment staff tightly, and that impact depends in part on whether the limit correlates in some way with the patterns of investment returns. Responsibilities may limit opportunities in a variety of categories. Institutional investors may have to concentrate in certain jurisdictions and/or avoid others, favoring a home economy or accepting broader prohibitions in an investable economy. Similarly, the organization may voluntarily restrict activity in particular capital markets, as investors often do when they choose not to lend securities in significant names or at significant times. Institutional investors also commonly limit their universes with investment policies in industries like coal, tobacco, or armaments.

Investor Responsibility for Racial and Gender Diversity in the Portfolio Company

An Example

Racial and gender diversity in the portfolio company is an evolving area of responsibility for investment organizations and, on 17 February 2021, FCLTGlobal hosted a small workshop for investor Members to explore and address the implications for them. A major topic of discussion about diversity in the portfolio company is the importance of data that meets investors’ standards. One asset manager shared how, in that firm, data are helpful but not always necessary: “We need to agree more on disclosure… But in the meantime, investors can ask qualitative questions, drive disclosure efforts, and throw a big fishing net on the data you can get.”

Long-term investors recognize the externalities of their portfolio companies as well. The implication of an “externality”—a cost created by one business but borne by others—is that the business and its investors can shirk the cost. Many investment institutions increasingly feel that they have responsibilities not to shirk costs that they help to create, such as climate and environmental impacts. [5] Investment organizations’ tax strategies are coming under similar scrutiny, as is their role in the inequities of marginalized racial and ethnic communities, and many other issues. [6] [7] [8] [9]

Delivering sustained—rather than fleeting— performance can be a responsibility, but many strategies that maximize value today do so at the expense of cumulative performance over time, like allocating to short-term activists who generate return by pulling earnings forward. Indeed, fulfilling the organization’s purpose may mean living through the discomfort of markets to deliver long-term performance. Marcus Frampton, Chief Investment Officer of Alaska Permanent Fund Corporation, noted this point in the context of market volatility resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. “I think everyone didn’t sail through March [2020] that well,” he observed, “but these tests are the ones that show whether you’re being financially responsible with your portfolio.” [10]

Investors’ Recent, Real-World Cases of Responsibility

- Future Fund is Australia’s sovereign wealth fund, and its government sponsor has given it an investment mandate that “requires the Board to act in a way that… is unlikely to cause a diminution of the Australian Government’s reputation in financial ” [11] Staff anticipated and acted on the fact that its reputation rests, in part, on the reputation of its asset managers. They began a dialogue with external asset managers on that basis, documented learnings from those interactions in a formal way, and established a guide for their ongoing conversations about stewarding the fund’s reputation. [12]

- New Zealand Super Fund is a sovereign wealth fund with all of the responsibilities implied by sovereignty. It launched its social media collaborative engagement “after the 2019 Christchurch terrorist attack,” in an effort “to lead a global investment collaboration to engage with the world’s three leading social media companies: Facebook, Alphabet (YouTube) and Twitter.

- The objective of the engagement is for these social media companies to strengthen controls to prevent the live streaming and distribution of objectionable content.” [13]

- Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF) put a spotlight on the issue of responsibility with its December 2019 decision to suspend equity It based that decision on concern that the practice is “inconsistent with the fulfillment of stewardship responsibilities of a long-term investor,” notwithstanding the US$346 million in revenue generated over three years by share lending, through 2018. GPIF continued: “Moreover, the current stock lending scheme lacks transparency in terms of who is the ultimate borrower and for what purpose they are borrowing the stock.” [14] Hiro Mizuno, Chief Investment Officer of GPIF at the time of this decision, detailed part of this concern at a 2020 seminar co-hosted by FCLTGlobal and the Pacific Pension Institute: “Sometimes the engagement manager knocks on the door of the CEO the day after they sold everything.” [15]

- State Street Corporation, one of the world’s largest servicers and managers of institutional investments, also feels responsibility related to equity lending and stewardship. In a summary of a published interview with Marty Tell, State Street’s Global Head of Securities Finance, Patricia Hudson, State Street’s Global Head of ESG Strategy, concluded that “the key for responsible investors is to weigh carefully the costs and benefits of lending versus retaining shares and to acknowledge the important market structure role equity lending plays in promoting liquidity and price discovery. They also must be transparent with their security lending agent on their preferences and priorities and have a clear governance process in place.” [16]

- The COVID-19 pandemic challenged many institutional investors that allocate to physical Keeping critical infrastructure activeduring this time compromised return because of plummeting demand—yet it also revealed new ways in which some institutional investors can fulfill their purposes. Bryan Lewis, Chief Investment Officer at US Steel, has observedthat “we can focus more on real assets, more on commodities, more on diversified opportunities that I think are a lot more tangible, that also have a greater connectivity to the broader economy.” [17]

- APG and PGGM are Dutch pension investors. APG has the “ambition to achieve attractive and sustainable investment returns for our customers, in a responsible way. So that we can always ensure a good and affordable pension. For current and future generations.” [18] PGGM shares very similar values, indicating that “we primarily exist to serve the health and welfare sector… we support the financial future of people working in this sector and we contribute towards a healthy and vital sector.” [19] These and other Dutch pension funds learned from a 2007 televised investigative report that they held stock in companies which also manufactured components of landmines and cluster munitions. [20] Both accepted responsibility, acknowledging Dutch expectations, and began divesting the positions within a month. [21] This encounter is now a common case study in the Netherlands. [22]

Defining Expectations and Responsibilities

Many important responsibilities for investment organizations are not new or evolving; they already are formalized in law, regulation, or contract. These legal, regulatory, and contractual responsibilities are out of scope for this research because investment organizations generally do not have discretion relative to these issues. Please refer to FCLTGlobal’s prior research and publications on the topics of fiduciary duty, mandate contracts, and asset stewardship. [23] [24]

- Fiduciary duty defines the legal obligation that an asset owner has to its sponsors and savers and that an asset manager has to its clients.

- Mandates usually detail the contractual responsibilities that an asset manager accepts as part of an investment agreement with an asset In some parts of the world, “mandates” also include the requirements that sponsors set for asset owners.

- Stewardship encompasses the responsibilities of investment organizations, both asset owners and managers, to companies in their portfolios. One example is requiring funds to cast the proxy votes to which their shareholding entitles them.

Throughout this post, we center our analysis of new and evolving circumstances on the terms purpose, expectations, responsibilities, and constituents, and we define those terms as follows:

- Purpose is the reason that an investment organization Return objectives are not an organization’s purpose. Purpose is the outcome that meeting return objectives enables.

- Expectations are the broadest possible set of behaviors or outcomes for which others will try to hold an investment organization accountable.

- Responsibilities are those expectations for which an investment organization actually has accepted accountability.

- Constituents are the people and organizations outside of the institutional investor’s executive management structure who may be able to hold it accountable for fulfilling its purpose.

Investment organizations now usually have the opportunity to judge which expectations translate to responsibilities for them. Yet advocacy movements are working to reset the standards to which investment organizations are held. B Lab and The Shareholder Commons argued in a September 2020 report, for instance, that “laws and regulations must be changed to require business and financial institutions to look beyond their own financial returns and take responsibility for the impact they have on the social and ecological systems on which a more just, inclusive, equitable, and prosperous economic system depends.” [25] As Martin Lipton and Sabastian Niles also pointed out in a Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz memo, “corporations and institutional investors have in their own hands whether they are going to be subject to the type of legislation and regulation proposed by [these advocates].” [26] These authors and others further emphasize this choice between leading and being led in A New Paradigm.

Indeed, the wheels have already been set in motion, with a variety of regulatory reforms being actively considered across jurisdictions…Any regulatory mandates and restrictions imposed on institutional investors and corporations to address the problems of short-termism may well include heavy-handed, overly broad or costly mandates that do not afford investors and corporations flexibility in tailoring solutions that will best promote a long-term perspective. Private ordering… by corporations and investors who best know their respective concerns and needs is more likely to result in effective and balanced solutions than government intervention. [27]

How Expectations Become Responsibilities

A new or evolving responsibility for an investment organization begins as an expectation for how that organization will behave. The most important distinction between an “expectation” and a “responsibility” is whether actual accountability has been accepted. Investment organizations are not accountable just because someone expects something of them, but they become accountable when that expectation translates into a responsibility.

Investment organizations face choices about whether to drive, accept, decline, or defer expectations as responsibilities.

Investor Responsibility for Economic Impact at Home and Abroad

An Example

Economic impact at home and abroad is an evolving area of responsibility for investment organizations and, on 22 July 2020, FCLTGlobal hosted a small workshop for investor Members to explore and address the implications for them. One asset owner that has accepted this responsibility in specific contexts abroad finds that trust is a prerequisite. “When it comes to trust, there is a constant need to tend the garden.” Even in an organization that is generally trusted, “trust must be maintained and reintegrated as regulators and governments change over time.” Such trust can be maintained based on “how you behave toward your community and examples of what you do in your own country.”

- Driving a new or evolved responsibility involves active leadership. Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec has taken this position, including with regard to climate-change mitigation. For example, then-CEO Michael Sabia commented at the creation of the Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance that “there are so many opportunities to earn commercial returns by investing in low-carbon solutions and to work with portfolio companies to decarbonize.” [28] This is the essence of “driving” a responsibility—finding investment opportunity by creating the responsibility.

- Accepting a responsibility means that the organization recognizes the expectation and shoulders accountability for fulfilling Participating in the process of corporate democracy is a recent example. Various parties have the expectation that investment organizations will vote the ballots that come with their shares, and many investors have agreed with that stance, even to the point of defending that responsibility publicly when the US Department of Labor challenged it in 2020. [29]

- Declining responsibility happens when an investment organization determines than an expectation is ungrounded or irrelevant and chooses not to assume accountability for it. One example is market liquidity. The assertion that investment organizations have responsibility for liquid markets is common, but it is an expectation for which many have declined responsibility. “We’re a provider of liquidity in various ways because we’re countercyclical,” remarked Marlene Puffer, President and CEO of CN Investment Division, at a 2020 seminar co-hosted by FCLTGlobal and the Pacific Pension Institute. “We may not think we have a responsibility to

provide liquidity, but we do provide it.” [30] - Deferring responsibility reflects an agreement in principle with the root expectation but also the need for certain conditions to be met before taking responsibility. For instance, an asset owner may accept responsibility for disfavoring a particular economy or sector, fulfill that responsibility in its actively managed portfolio, but defer the responsibility specifically within its externally-managed indexed portfolio unless or until it takes control of managing that money internally.

Determining which expectations to drive or accept as responsibilities, rather than defer or decline, is based on the long-term purpose of the investment organization, its constituents, and the trade-offs that accepting such a responsibility would entail.

Purpose is the reason that an investment organization exists and why it delivers performance. Translating the broad, aspirational, qualitative language that commonly frames a purpose into practical instructions for investors can be difficult, and some short-cuts have become common. Specifically, many investment professionals consider their purpose to be maximizing financial value within the boundaries of law, regulation, and contract, and they expect that executive management and board trustees will put that money to work from there to fulfill the organization’s higher-order purpose.

General examples of investment organizations’ purposes include providing for the well-being of retirees, preparing scholarship students to participate in the workforce and society, defending a currency, contributing to the economic development of a country, insuring the essential assets of people and companies, providing broad access to markets for those who would not otherwise have it, and pairing individuals’ and institutions’ savings with businesses that can innovate and grow. These are the approximate purposes of a pension fund, a university endowment, a central bank’s investment

arm, a sovereign wealth fund, an insurer, and asset managers, respectively. Recognition of an organization’s purpose serves as a reminder that how financial performance is delivered can matter just as much as the performance itself. For instance, selling a local company in the private-equity portfolio to an international conglomerate may not be purposeful for a sovereign development fund, even if the return on investment is strong. The same may be true for a pension fund investing in a company with a heavy pollution footprint in the community.

Constituents are the people and organizations outside of the institutional investor’s structure who may be able to hold it accountable for fulfilling its purpose (as shown in Figure 2). Which constituent has raised an expectation and the avenue through which it is attempting influence can increase pressure, as can collaboration among constituents.

Some constituents are those that supervise institutional investors:

- Sponsors such as a university for an endowment or a corporate parent for a defined-benefit pension are the ultimate decision makers. They exert direct and decisive influence for asset owners because they have the power to dictate the terms of bylaws and contracts, as well as to make personnel choices. In the most consequential cases, a sponsor can change the purpose of a fund to conform to the sponsor’s own expectations.

- Savers entrust sponsors to invest for their benefit and, in the aggregate, can influence the sponsors in ways similar to those in which the sponsor can influence the asset owner. Collective-action challenges make it difficult for savers to act in the aggregate, so their influence can be less direct or even disjointed when they do not act collectively for an expectation to become a responsibility.

- Governments often are the saver in and the sponsor of an investment organization, including in the case of public pensions, central banks, and sovereign wealth and development funds, and they can act directly and decisively in those capacities. Governments also make legislation and regulations that apply to investors broadly, in which cases investors may have some room for interpretation and discretion about how an expectation translates to a responsibility.

- Asset owners are investment organizations with their own responsibilities and also constituents that, in their capacity as clients, shape the responsibilities of other investment organizations, especially asset managers. Specifically, they often are the “term makers” for contracts, and they choose which management firms to hire and fire. Future Fund addressed this relationship in an internal 2018 report: “The workings of the investment value chain, the relationships and interdependencies that exist, are increasingly exposed to public view and scrutiny. Expectations of who should be held accountable are changing. Those in the investment chain can no longer be confident that issues that arise elsewhere in the chain will not touch them.” [31] Asset owners also can be contract “term takers” when they invest in commingled funds, whether in the public or private markets, but this investment choice is itself an expression of responsibility. Allocating in this way does not alter responsibilities that belong to the institution.

Constituents that support institutional and retail savers also are important.

- Asset managers are institutional investors who support asset owners and individual savers (the latter also known as retail investors). Many asset owners access the markets through asset managers, either totally or in part, and most retail investors save through mutual funds that asset managers offer. Asset managers choose the investment strategies that they will provide, including how and with whom they will invest. In the context of owner relationships, they have the option of whether or not to accept a particular client, and they may choose not to do so for reasons ranging from capacity to concern about an owner’s alignment with their investment beliefs, strategies, or processes. In the context of retail relationships, the mutual fund or UCITS (Undertakings for the Collective Investment in Transferable Securities) board has an owner-like role and all of the responsibilities associated with it.

- Capital market intermediaries are institutional investors’ interface with companies, which for the purpose of navigating responsibilities includes exchanges as well as investment banks and index providers. All get to choose their offerings, and many have chosen in recent years to tailor their business based on their views of responsibility, ranging from diversity to the impact of share-class structures on corporate democracy. [32] [33] [34]

- Companies have expectations for how their investors will behave—for instance, that their investors will exercise the rights given to them in the system of corporate democracy. Their ability to influence institutional investors with these expectations may be indirect, through other actors such as government and media.

- Workforce in this context is the people who work for asset owners, asset managers, and companies. It is only through these people that organizations take action and create value. Many workers can choose the activities in which they are willing or unwilling to take part, and they can pressure their organizations to enshrine their expectations as responsibilities. [35] [36] [37]

Other types of institutions do not have direct control but amplify the effect of others, either purposefully or incidentally.

- Peer institutions lend legitimacy and momentum to expectations when they accept them as new or evolved responsibilities. This effect may or may not be intentional. When it is intentional, these institutions can directly encourage their peers to join them in the effort. For instance, Generation Investment Management has committed to working “with others to achieve five societal objectives by 2025,” including “commitments by all asset managers, asset owners, insurance companies and banks to a 2050 or sooner net zero target with robust portfolio alignment reporting.” [38] Even when they do not have a goal of influencing others, the constituent that raised an expectation can learn from the circumstances that led to success with a particular institution and seek out peer institutions in similar circumstances in an attempt to repeat that success.

- Media chooses which stories are told at a broadcast scale, and this often determines which issues get attention from all other constituents. Fact-based journalists do not advocate for their own expectations of institutional investors, but the issues that they choose to cover, or not, shape the expectations of other institutions. This is a very influential role, even though it is indirect, and expectations often emerge or evolve in response to media reporting or “headline risk.”

- Society includes the customers of business and the community in which the business operates. Expectations may be strongest and most durable when society expresses them in an organized fashion, which can include divestment campaigns against institutional investors, boycott campaigns against companies, and a suite of pressure campaigns on government ranging from social media to lobbying and all the way to civil unrest. [39]

Trade-offs are inherent in determining which responsibilities to accept. Institutional investors face a very complex challenge in choosing which expectations to drive or accept as responsibilities and which to defer or decline. Judgment is inherent, decisions can change, and no formula can provide a “correct” answer.

In addition to the complexity of a single expectation, investors grapple with multiple existing responsibilities at the same time, so optimization for any one responsibility is impossible and trade-offs are constantly necessary, despite being uncomfortable and delicate.

The guiding question for investors is whether accepting an expectation as a responsibility, and making trade-offs accordingly, would result in the organization being more able to fulfill its purpose. If so, making the trade-offs and accepting the responsibility is the best course of action; if not, deferring or declining the responsibility is better.

Investor Responsibility for Climate and Environmental Impact

An Example

Climate and environmental impact are evolving areas of responsibility for investment organizations and, on 22 April 2021, FCLTGlobal hosted a small workshop for investor Members to explore and address the implications for them. “We felt collectively that we will be called upon to” make a net-zero 2050 commitment, shared one asset owner, and “we wanted to ensure that the plan was well prepared and well positioned. There was a lot of uncertainty, and it was significant for us to get into this commitment without having all the answers.” Fulfilling this responsibility, now that it has been accepted, is the core challenge facing investment organizations in this position.

Five Steps for Investors to Operationalize Their Responsibilities

We learned in the course of numerous case studies with FCLTGlobal Members that long-term investment organizations take at least five steps, after reconfirming their purpose, to operationalize their responsibilities.

Long-term investment organizations take these steps sequentially in some circumstances but, in others, they will revisit prior steps based on learnings along the way, jump to subsequent steps when change happens so fast as to require it, or otherwise act out of sequence. Importantly, long-term investment organizations take these steps deliberately.

Reconfirming the organization’s purpose is the foundation of this process. Every subsequent decision will refer to this purpose. Giving attention to purpose and affirming it will establish purpose as the frame of reference for all involved.

“Framing” the minds of decision makers in this way will affect their behavior, namely which external expectations they accept and which they decline as responsibilities later in this process.

The default frame of mind for making these decisions easily can be the routine work of investment decision makers: beating a particular benchmark, achieving a certain type of exposure, or controlling the profile of risk. Yet these are instruments for accomplishing the organization’s purpose, not the purpose itself. The act of remembering and writing down the organization’s purpose will reframe minds so that decisions about responsibility are made on those terms. In their groundbreaking 1981 research, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman explained this behavioral framing effect in the context of mythical Ulysses being bound to the ship mast to avoid the Siren-song coming from the dangerous rocks. That explanation translates in this context also—pre-committing to purpose can keep an investment organization from making decisions about external expectations that are expedient in the short term but irresponsible in the long term. Tversky and Kahneman concluded in more scientific terms that “one may discover that the relative attractiveness of options varies when the same decision problem is framed in different ways. Such a discovery will normally lead the decision maker to reconsider the original preferences, even when there is no simple way to resolve the inconsistency. The susceptibility to perspective effects is of special concern in the domain of decision-making because of the absence of objective standards.” [40]

1. Taking inventory of current responsibilities also is important for establishing a frame of reference. Every organization, except for those just created, will have existing responsibilities and will have to make future decisions about responsibility in this context. In contrast, organizations do not have the luxury of making decisions in isolation because the commitments and resources required to fulfill existing responsibilities will affect which new and evolving expectations that an investment organization can accept. Long-term investment organizations note the constituents and trade-offs associated with each responsibility in their inventory because accepting a new responsibility can alter those previous decisions. Knowing which constituents might be encouraged or upset by new responsibilities or trade-offs is important groundwork for the decision-making process. Investment organizations consider the comprehensive set of trade-offs they have accepted, in addition to the individual trade-offs as they arise.

Institutional investors can benefit from keeping this inventory very clear and succinct so that they can

use it in board, client, and public communications.

2. Anticipating emerging expectations is an ongoing activity for long-term investment organizations because the investment organization does not choose when new expectations will arise. Investment organizations can be proactive by originating new responsibilities for themselves but will also need to respond to constituents’ expectations. Anticipating expectations as early as possible permits long-term investment organizations to prepare to drive, accept, defer, or decline them as responsibilities. Understanding the position and pressures of constituents may allow anticipation of expectations. The intention is to think ahead and consider their perspectives in order to anticipate how their expectations might change. Having strong relationships with constituents and seeing their emerging expectations allows an investment organization to shape those expectations and adapt to changing expectations. Yet the inverse also is true and raises the stakes of the relationship: disorganized or distracted interactions can undermine trust and lead to expectations becoming more confrontational.

Part of anticipating these expectations is knowing the boundaries of trade-offs that the investment organization could accept. This clear boundary-setting process can help investment organizations narrow the scope of their work. Expectations that come with trade-offs beyond the boundaries that an investment organization could, or would, accept can be declined more easily.

As with the inventory of existing responsibilities, investors can benefit from keeping this list of anticipated expectations very clear and succinct so that they can use it in board packages or other communications. Unlike inventorying existing responsibilities, however, anticipating expectations is much more complex and dynamic than just list-making. The goal is to elicit the critical thinking needed to anticipate new expectations, not simply to make a list.

3. Processing emerging expectations comes after anticipating them, once they have arrived for decision by the investment organization. A sequence of four key gating questions can help an investor

determine whether an expectation conveys a responsibility:

- Would accepting this expectation as a responsibility advance our purpose?

- Is this expectation relevant to our organization?

- Is it possible for our organization to meet this expectation?

- Does our organization have capacity to meet this expectation?

We present these questions as a process on page 26 of the complete publication.

The mechanics of this process are important. Decisions to drive or accept a responsibility are clear when the answers to all of these questions are “yes,” and decisions to defer or decline expectations are clear when the answer to any of these questions is “no.” Clear and conclusive answers may be less common; partial answers, like “perhaps,” may be more common. Long-term investment organizations will accept trade-offs that result in the organization being more purpose-oriented overall and decline those that do not.

Investor Responsibility at Impasses in Corporate Engagements

An Example

Decisions about whether, or how, to maintain holdings in issuers that are unresponsive to engagement provide real-world evidence about investors’ responsibilities. On 7 December 2020, FCLTGlobal hosted a small workshop for investor Members to explore and address the implications for them. The asset management company Schroders spoke of its responsibility to exhaust “all engagement options before determining that dialogue with a company is at an impasse” and said that it uses divestment as a last resort. After the workshop, FCLTGlobal and Schroders published an article detailing Schroders’ approach to navigating impasses in corporate engagement. [41]

Distinguishing the criteria of being “purposeful” and “relevant,” expressed in the first two of these questions, is important. It is possible for an expectation to advance an organization’s purpose but not be relevant to it. Consider, for instance, a hypothetical public pension plan for educators with the purpose of supporting the education sector and contributing to its vitality. An expectation may arise for the organization to favor education technology ventures. That expectation is potentially aligned with the organization’s purpose but not relevant: allocating to ventures irrespective of their expected return is a form of grant-making, not pension finance, and therefore not relevant to a pension investment organization.

Investment organizations finish this part of the process by making their decision to drive, accept, defer, or decline a new or evolved responsibility.

4. Fulfilling a new responsibility is an obligation after an investment organization has decided to drive or accept it. This requires collective effort across the institution, including not only the investors but also the legal, communications, compliance, human resources, executive, and governance functions.

Fulfilling responsibility in a standard manner is difficult because investment organizations are so large and complex. Investors have emphasized to FCLTGlobal that the task of operationalizing new or evolved responsibilities is entirely different from determining that they exist and that consistency is potentially the most challenging part of operationalizing investor responsibilities. One investor observed that fulfilling these responsibilities is not something it can do just by exhorting and encouraging individuals. The institution must organize to fulfill them. “But how?,” the investor asked. Another described the internal struggle to find a common language around this issue and remarked, “There are some who are less involved in this work who view this responsibility as impact investing and impact investing as charity.”

Views like these reveal a delicate management task. Many staff, including investors, may be burdened by trade-offs but not in a position to see firsthand the responsibility that requires them. Internal frustration, disagreement, and disorganization are clear risks. Indeed, investors can see the change for what it is—a reframing of their work so that “maximizing value” goes beyond the narrowest letter of law, regulation, or contract. Long-term investment organizations reward staff across the institution for helping to fulfill the organizations’ responsibilities and hold staff accountable if they do not.

Responsibilities are not implemented by fiat, however. Frontline staff in various functions may have the best view of trade-offs created by accepting a new responsibility. Long-term investors grapple honestly with those trade-offs so that staff can fulfill a responsibility. No amount of structuring and institutionalizing will operationalize a responsibility if staff are given incompatible goals.

Long-term investment organizations consider relationships, strategy, staffing, risk management, success metrics, and time horizon in fulfilling their responsibilities. Asking and answering a series of questions can help an investment organization determine whether it is fulfilling a new responsibility.

- Degree of responsibility: Accepting responsibility does not necessarily mean accepting it alone. Rather, the first step of fulfillment is knowing which other organizations, if any, share the responsibility. An investment organization’s responsibility may be sole, primary, or secondary. Knowing this extent of responsibility and which other organizations are involved will influence subsequent decisions about fulfillment.

- Overall investment strategy: Adjusting investment strategy is perhaps the most obvious way that investment organizations can implement decisions about responsibility. These organizations do not exist for the purpose of earning some particular return, but investing is their instrument for accomplishing their purpose. They exercise influence and respond to influence through the ways that they invest.

- Staff metrics: People implement strategies. Provided that the organization has hired the right people given its responsibilities, those people will behave accordingly so long as the organization is consistent in its focus, rather than saying it wants one thing and signaling elsewhere, in processes such as remuneration calculations or expansions of internal mandates, that it wants another.

- Risk management: Just as staff metrics can buttress or erode people’s focus, the risk parameters placed on an investment strategy can do the same for the organization itself. Accepting a responsibility amounts to changing how the organization will invest, usually without changing expectations of performance, and that means taking different risks. A strategy can work only if the parameters around it allow the organization to take on new risks, such as those associated with limiting the investable universe, booking externalities, and/or extending the required durability of performance over certain time horizons.

- Judging overall success: Rigorous processes tied to effective outcomes are necessary for an investment organization to credibly fulfill its responsibilities. An investment organization may have processes—strategy, metrics, risk management—for fulfilling responsibilities that are rigorous but ineffective. It is also possible to get lucky by being effective despite weak processes. Long-term investment organizations need methods to assure both the integrity of their processes and the effectiveness of their outcomes.

- Time horizon: Most responsibilities are continuous. Having a responsibility will come with a time frame for continuing to fulfill it. This process of operationalizing—including anticipating change—is routine for a long-term investor.

- Making adjustments: Institutional investors can expect rigorous processes for fulfilling a responsibility to occasionally be ineffective as new information arises or conditions change. Long-term investors behave responsibly not by committing permanently to their decisions but instead by adjusting and looping their new knowledge back into their decisions.

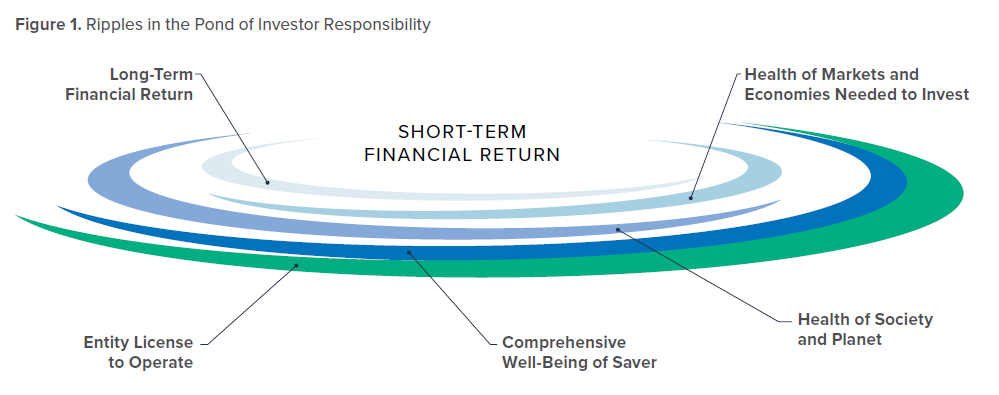

5. Communicating about responsibilities will be a component of fulfilling them for many long-term investment organizations because they will often need help from external collaborators and because the constituents that originated particular responsibilities will want verification. Consistency is necessary in this task too. Being consistent means having an answer to the question, “Who communicates our responsibilities, to whom do they communicate, and in what ways?” It also means that everyone involved in this communication shares an understanding of the division of labor. A chart that integrates and visually depicts these roles can assist with that shared understanding efficiently.

- By whom: Long-term investment organizations will have the right leaders ready to communicate about responsibilities relevant to their role. Organizations listen to their leaders, and investment organizations reliably fulfill their responsibilities only when their leaders communicate about these responsibilities consistently. Staff and other stakeholders may need or expect certain messages to come from certain leaders—and perhaps not from others. The messenger can matter as much as the message, so long-term investment organizations pick the right messenger based on the responsibility that is being communicated.

- To whom: Investment organizations often cannot fulfill a responsibility alone. Fulfillment depends to some extent on behavior by sponsors or clients on one side of an investment decision and by the portfolio companies on the other—as well as on the behavior of other organizations that may share the responsibility. Additionally, the constituents whose influence led to a new responsibility may reasonably expect verification before they consider the responsibility fulfilled. Communicating new or evolved responsibilities to others is part of fulfilling them in these cases. Indeed, communication about responsibilities can be part of mandate contracts, along with other long-term provisions. [42]

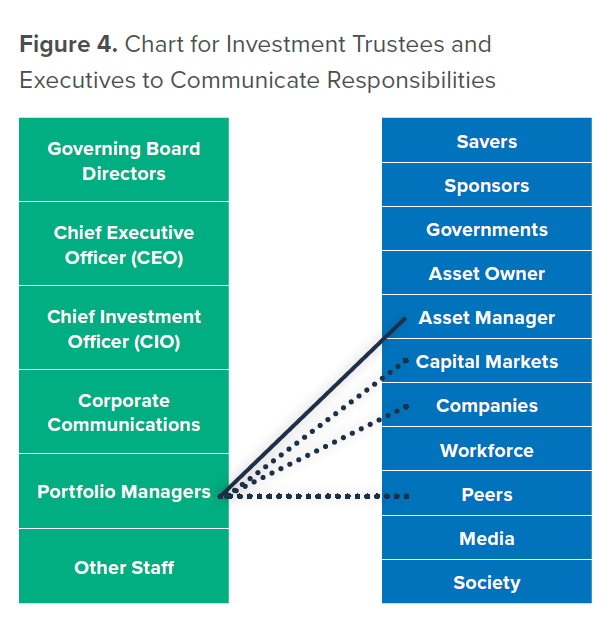

- Ways of communicating: How we communicate affects how others act, and there is a clear distinction between “telling” and “showing” (as shown in Figure 5). Broadly telling others about new responsibilities likely is sufficient when no action is required other than being informed, and it may also be sufficient for setting absolute and simple rules. Many institutional investors also will have responsibilities that can be met only in collaboration with others, like portfolio companies, third-party advisers, and—in the case of asset owners—the external managers that they hire. Collaborating consistently over time may involve showing these third parties the contours of responsibilities using methods such as structured interactions, scenario exercises, or even firsthand experience (e.g., attending client trustee meetings, regulatory hearings, or constituent engagement meetings).

Conclusion

Anticipating, fulfilling, and communicating responsibilities is a necessary long-term behavior for investment organizations because it preserves their strategic focus. Otherwise, organizations risk disruptive decisions by their constituents. Focusing on the long term is possible only if the organization can focus at all, rather than reacting to disruption or, in a worst-case-scenario, losing its license to operate.

Investor Responsibility for Equity Lending and Stewardship

An Example

Equity lending and stewardship are evolving areas of responsibility for investment organizations and, on 20 August 2020, FCLTGlobal hosted a small workshop for investor Members to explore and address the implications for them. The discussion made it clear that experiences of institutional investors with equity lending vary widely in terms of both why investment organizations choose to lend or not and how they do so. The result is that perspectives on responsibility range from abstaining altogether to viewing lending as a necessary tool. For example, one asset owner said, “We don’t lend domestic shares” because “having shares out would [be a] detriment” to engaging with these high-priority companies.

There are numerous examples of new and evolving responsibilities, including addressing social issues, environmental challenges, geopolitical concerns, or development needs. Such challenges illustrate the changing landscape of investor responsibilities, including the consequences on long-term focus.

Behaving responsibly is an intensely complex and ongoing challenge in practice. Feedback loops and interactions make the work perpetual, the most consequential decisions hinge on judgment rather than formula, and the circumstances that justify decisions will shift. Long-term investment organizations use processes and management practices to maintain their responsibilities as a result.

Ripples of Responsibility assists long-term investment organizations in two ways. The first is by developing an understanding of the concept of responsibilities for investment organizations. The second is by providing a toolkit for navigating these circumstances, including tools for anticipating, fulfilling, and communicating responsibilities.

Expectations of long-term investment organizations expand well beyond common notions of their purpose to include their broader impact on markets, society, and the environment. Determining which expectations to accept as responsibilities is based on the long-term purpose of the organizations, its constituents, and the trade-offs that accepting such responsibilities would entail. As investment organizations consider the ripples on the pond that the stones of expectations can cause, we hope that this research and toolkit help them navigate to long-term opportunity.

The complete publication is available here.

Endnotes

1Corporate Reputation in the Investment Industry,” Future Fund Research Report (unpublished), 2018.(go back)

2“Social Media Collaborative Engagement,” New Zealand Super Fund, 20 March 2020, https://www.nzsuperfund.nz/how-we-invest/responsible-investment/collaboration/social-media-collaborative-engagement/.(go back)

3International Corporate Governance Network, ICGN Guidance on Fiduciary Duties (London: ICGN, 2018), http://icgn.flpbks.com/icgn-fiduciary_duties/. Note: In 2018 ICGN members approved a new ICGN Guidance on Fiduciary Duties to extend investor duties beyond “care” and “loyalty” to address the impact of systemic risk, time horizons, and governance as part of stewardship obligations. The following year, the European Commission announced mandatory disclosure by investors around “the extent to which ESG [environmental, social, and governance] risks are expected to have an impact on returns.”(go back)

4“Corporate Reputation in the Investment Industry,” 1.(go back)

5Adam Morton, “Investors Lead Push for Australian Business to Cut Emissions More Than Government Forecasts,” The Guardian, 13 October 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/oct/14/investors-lead-push-for-australian-business-to-cut-emissions-more-than-government-forecasts(go back)

6Norges Bank Investment Management, “Tax Management,” 2019, https://www.nbim.no/en/organisation/governance-model/policies/tax-management/.(go back)

7Future Fund Board of Guardians, Statement of Investment Policies September 2020, 34–35, https://www.futurefund.gov.au/-/media/future-fund—documents/investment-policies/202009—ffbg-statement-of-investment-policies.ashx?la=en&hash=A95FE47D98B7AD78C7F3D3C05FACAA51DCA48F65(go back)

8“Going Long Podcast: Leo Strine,” FCLTGlobal, 16 November 2020, https://www.fcltglobal.org/resource/going-long-podcast-leo-strine/. Note especially Justice Strine’s remarks in minutes 21 and 23 of this tape. In the former, he observes that “the share of profits that have gone into worker pay from increases in productivity and profitability has gone way down in the last 30 years, and activist pressures have been a big part of that. That has created much greater economic insecurity in the US, has led to nativist appeals, and… we are not closing the racial equity gap.” He continues in the latter segment, saying, “these companies had 10 years to build up reserves. Why didn’t they do it? I think it’s because, to be honest, if they had any reserves, they would get savaged, as you know, by activists. Part of why they didn’t give workers things is because, frankly, some of the short-termism debate is a little off.”(go back)

9“Risk Webinar Series: Ramifications of Investment Risk Management on Income Volatility and Distribution,” FCLTGlobal, 10 February 2021, https://www.fcltglobal.org/resource/risk-webinar-series-ramifications-of-investment-risk-management-on-income-volatility-and-distribution/.(go back)

10“Crisis as Catalyst: Resetting Investor Responsibilities,” PPI webinar in partnership with FCLTGlobal, 07 May 2020, https://vimeo.com/416142954.(go back)

11“Future Fund Board of Guardians— Statement of Investment Policies,” Future Fund, September 2020, 5, https://www.futurefund.gov.au/-/media/future-fund—documents/investment-policies/202009—ffbg-statement-of-investment-policies.ashx?la=en&hash=A95FE47D98B7AD78C7F3D3C05FACAA51DCA48F65(go back)

12“Corporate Reputation in the Investment Industry,” 1.(go back)

13“Social Media Collaborative Engagement,” 2.(go back)

14“Suspension of Stock Lending Activities,” GPIF, December 2019, https://www.gpif.go.jp/en/topics/Suspension_of_Stock_Lending_Activities.pdf.(go back)

15“Crisis as Catalyst: Resetting Investor Responsibilities,” 10.(go back)

16State Street Corporation, Aligning Responsible Investing with Securities Lending (Boston: State Street, 2020), 7, https://www.statestreet.com/content/dam/statestreet/documents/Articles/aligning-responsbile-investing-with-securities-lending.pdf.(go back)

17“Risk Webinar Series: Ramifications of Investment Risk Management on Income Volatility and Distribution,” 9.(go back)

18“About APG—Asset Management,” APG, https://apg.nl/en/about-apg/asset-management/.(go back)

19“About Us—Our Mission,” PGGM, https://www.pggm.nl/en/about-us/our-mission/.(go back)

20Carolyn Bandel, “Dutch Funds Invest in ‘Cluster Bombs and Land Mines’—TV Claims,” IPE, 19 March 2007, https://www.ipe.com/dutch-funds-invest-in-cluster-bombs-and-land-mines-tv-claims/21620.article.(go back)

21“Dutch ABP, PGGM Say Sold Shares in Weapons Producers,” Reuters, 06 April 2007, https://www.reuters.com/article/instant-article/idUKL0648692120070406.(go back)

22Suzanne Oosterwijk, Dutch Case Study: A Ban on Cluster Munitions (Utrecht: PAX for Peace, 2015), https://stopexplosiveinvestments.org/wp-content/uploads/PAX_Rapport_Disinvenstments_FINAL_DIGI.pdf.(go back)

23Matthew Leatherman et al., Institutional Investment Mandates: Anchors for Long-Term Performance (Boston: FCLTGlobal, 2020), https://www.fcltglobal.org/resource/institutional-investment-mandates-anchors-for-long-term-performance/.(go back)

24Bhakti Mirchandani et al., Model Stewardship Code for Long-Term Behavior (Boston: FCLTGlobal, 2019), https://www.fcltglobal.org/resource/model-stewardship-code-for-long-term-behavior.(go back)

25Frederic Alexander, Holly Ensign-Barstow, Lenore Palladino, and Andrew Kassoy, From Shareholder Primacy to Stakeholder Capitalism (B Lab and The Shareholder Commons, September 2020), https://theshareholdercommons.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/From-Shareholder-Primacy-to-Stakeholder-Capitalism-TSC-and-B-Lab-White-Paper.pdf.(go back)

26Martin Lipton and Sabastian V. Niles, “The Spotlight on Investors—Proposed Expansive Regulation of Institutional Investors and Shareholder Behavior—Imposing New Fiduciary Duties on Investors (and Companies),” Wachtell, Lipton, Rozen & Katz, 29 September 2020, https://www.wlrk.com/webdocs/wlrknew/ClientMemos/WLRK/WLRK.27091.20.pdf.(go back)

27Martin Lipton, Steven A. Rosenblum, Sabastian V. Niles, Sara J. Lewis, and Kisho Watanabe, The New Paradigm—A Roadmap for an Implicit Corporate Governance Partnership Between Corporations and Investors to Achieve Sustainable Long-Term Investment and Growth (Wachtell, Lipton, Rozen & Katz and World Economic Forum, 2016), 7, https://www.wlrk.com/webdocs/wlrknew/AttorneyPubs/WLRK.25960.16.pdf.(go back)

28Michael Sabia, United Nations–Convened Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance testimonial, 2021, https://www.unepfi.org/net-zero-alliance/test-membership-page/.(go back)

29“Fiduciary Duties Regarding Proxy Voting and Shareholder Rights,” Federal Register, 04 September 2020, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/09/04/2020-19472/fiduciary-duties-regarding-proxy-voting-and-shareholder-rights.(go back)

30“Crisis as Catalyst: Resetting Investor Responsibilities,” 10.(go back)

31“Corporate Reputation in the Investment Industry,” 1.(go back)

32“Nasdaq to Advance Diversity through New Proposed Listing Requirements,” Nasdaq, 01 December 2020, https://www.nasdaq.com/press-release/nasdaq-to-advance-diversity-through-new-proposed-listing-requirements-2020-12-01.(go back)

33“Goldman Sachs’ Commitment to Board Diversity,” Goldman Sachs, 04 February 2020, https://www.goldmansachs.com/our-commitments/diversity-and-inclusion/launch-with-gs/pages/commitment-to-diversity.html.(go back)

34See rules on including companies issuing shares with multiple voting rights in S&P Composite 1500 indices at S&P Dow Jones Indices, “S&P Dow Jones Indices Announces Clarifications to the S&P U.S. Indices Methodology,” 20 December 2019, https://www.spglobal.com/spdji/en/documents/indexnews/announcements/20191220-1059762/1059762_US%20Indices%20methodology%20clarifications%20Dec%202019.pdf (go back)

35Employees of Microsoft, “An Open Letter to Microsoft: Don’t Bid on the US Military’s Project JEDI,” Medium, 12 October 2018, https://medium.com/s/story/an-open-letter-to-microsoft-dont-bid-on-the-us-military-s-project-jedi-7279338b7132.(go back)

36“Tell These Tech Companies to Divest from ICE & CBP Operations,” petition, Color of Change, https://act.colorofchange.org/sign/Microsoft_ICE.(go back)

37“Dear Sundar,” letter to Google CEO, NYT Files, 2018, https://static01.nyt.com/files/2018/technology/googleletter.pdf(go back)

38Generation Investment Management, “Senior Partner Letter,” 11 March 2021, 6, https://www.generationim.com/media/1819/gim_letter_210310_v2.pdf.(go back)

39Cecelie Counts, “Divestment Was Just One Weapon in Battle against Apartheid,” New York Times, 27 January 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2013/01/27/is-divestment-an-effective-means-of-protest/divestment-was-just-one-weapon-in-battle-against-apartheid.(go back)

40Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, “The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice,” Science 211 (1981): 5, http://www.stat.columbia.edu/~gelman/surveys.course/TverskyKahneman1981.pdf.(go back)

41“Schroders’ Approach to Navigating Impasses in Corporate Engagement,” FCLTGlobal, 28 January 2021, https://www.fcltglobal.org/resource/schroders-impasses-corporate-engagement/.(go back)

42Leatherman et al., Institutional Investment Mandates, 23.(go back)

Print

Print