The accountability processes of government and business are each ideal for optimizing different policy issues, and we get into trouble when we let one take on the role of the other. What has made the US capital markets the most robust and respected in the world is the combination of market- and government-based structures and especially the comprehensive transparency of our public companies. The nature of capitalism is to maximize profits, and it is up to the government to make sure that happens without externalizing costs onto the public who have no capacity to provide a market-based response. Corporate executives would always prefer less disclosure. Investors would prefer more. Because of the collective choice problem, there is no way for investors to make a market-based demand for more information as effectively and efficiently as having the government set the floor for what must be disclosed.

It is within this context that the questions will always arise about when it is time to add more to the already extensive information that issuers must provide to investors. As the request for comments and Commissioner Lee’s outstanding presentation on materiality suggest, that time has come for ESG. The reason it is the fastest-growing sector of investment vehicles is a reflection of increasing concerns about the inadequacy of GAAP numbers in assessing investment risk. Let me emphasize that; ESG and climate change disclosure concerns are entirely and exclusively financial. That is what makes them a have-to-have, not a nice-to-have.

This is not surprising. After more than a century of working with GAAP, there is still a lot of inconsistency in the way accounting rules are applied. GAAP may allow for a lot of options in disclosing the value of factory equipment, but at the end of the process, hard assets are something you can count and the tax code is helpful, too, in validating those numbers. And GAAP is based on data that corporations are already required to disclose in fairly consistent apples-to-apples form. ESG, which is a recent response to the inadequacy of GAAP in assessing investment risk, is still in its earliest stages. ESG factors are inadequately and inconsistently disclosed and harder to quantify. Even so, they are already vitally important in providing guidance that traditional GAAP cannot. GAAP is focused on what values are today. ESG is about evaluating the risks of tomorrow and five and ten years from now.

There is one thing ESG is unequivocally not: non-financial. Imperfect and inconsistent as ESG data are, they are entirely and exclusively methods for better assessing investment risk and return. The comments that claim otherwise, like those of the fossil fuel companies, have failed to provide a single example to prove that there is any trade-off in shareholder value. And when it comes to what shareholders need, the Commission should rely more on what investors say they need than what issuers would prefer to give them. As a matter of law and economics, investors have the fewest conflicts of interest in determining what they need to make a buy/hold/sell decision.

ESG is focused on factors that will affect the enterprise as a sustainable concern. Black Rock, for example, announced that it has added 1200 “sustainability metrics” to its calculus in 2020. The UK’s Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) was created by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to develop consistent climate-related financial risk disclosures for use by companies, banks, and investors in providing information to stakeholders. In the US, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) is merging with the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) to provide investors and companies a comprehensive corporate reporting framework to drive global sustainability performance.

Admittedly, there is no consensus and a lot of inconsistency in defining what ESG is, which is another reason to be grateful for the Commission’s involvement. The interest in ESG is far ahead of the capacity to assess or evaluate it. And, as with any topic that has reached the tipping point, a lot of people and organizations are slapping ESG labels on themselves to get a piece of the action, all the more reason for additional guidance from the Commission.

I have a brokerage account. The online interface now includes what they call an “ESG” analysis and a separate “impact analysis” tied to goals like ethical leadership and racial equality. It is not clear what data or which data providers are used for these assessments. There are ads on television now for “ESG-neutral” investment 2ndVote Funds. “ESG-neutral” is a meaningless term. The offerings include pro-gun and anti-abortion ETF filters that can only be categorized as Social. These are unquestionably ESG funds; the managers just assign different weights to the ESG factors than funds based on analysis that gun stocks, for example, may be a sub-optimal investment. That is fine, of course. Just as some portfolio managers may be buying a stock as others, even in the same organization, are selling it. What is important is making sure that investors have a clear idea of what factors and investment goals are the basis for those decisions. I note that despite repeated requests, 2ndVote has not provided me with their proxy voting policies or records of past votes, but it is likely that ESG analysis is involved in at least some of those votes. I look forward to reviewing their N-PX forms.

All of this further shows why we need clearer, more consistent information. When consumers demanded organic foods, government standard-setting was the only way to make sure that term was used only when it meets some consistent and supportable standard. That is where we are with ESG. The exponential increase in the use of ESG and related terms in investment and corporate communications makes it an urgent priority for guidance from the Commission to prevent misleading or confusing investors.

E, S, and G

We sometimes forget that E, S, and G are three very different categories, with very different levels of consensus and understanding about them.

For example, look at one small part of the almost catch-all category, S, for Social. The annual reports that accompany proxy statements almost always claim that the company’s greatest asset is its people. But GAAP tells us almost nothing about how to assess their value. How many PhDs? How many economists/MBAs/programmers/sales representatives? What incentives are provided for worker education and promotion? How is diversity supported by management? Other questions that might fall into the S of ESG could pertain to whistleblower protection, supply chain issues like the ones highlighted in the July 7, 2020 statement issued by four cabinet agencies, cybersecurity, and the increasingly controversial issue of political contributions. Or the possibility of a pandemic, a risk only a small fraction of issuers were prepared for in 2020.

The E can be misleading. Companies that have to disclose problems, violations, and fines may appear higher-risk than those that have not (yet) been the subject of investigations. As some of the commenters have already said, it is important that the E not be limited to a company’s carbon footprint. Every company has environmental risk, whether it is the direct result of operations or products, as in the fossil fuel industry, or the impact of climate change on supply chains, coastal properties, or insurance.

There is more consensus at the moment around the G factors. Many are thoroughly covered by state law and current SEC disclosure rules, like those pertaining to executive compensation, related party transactions, board member stock ownership and meeting attendance. I find, though, that the best way to judge governance effectiveness is to look at the results, rather than the policies, and “resume independence” does not always translate to more effective oversight. So, some improvement there might also be called for.

In all three categories, the Commission must make sure the focus is on what counts, not just what can be counted.

Evidence about the increasing sophistication of institutional investors in using ESG indicators to evaluate risk and return and the increasing importance of those factors:

Just a few examples:

- The Environmental Protection Agency published a 150-page document about coping with the debris from natural disasters across the country, which said, “Start planning for the fact that climate change is going to make these catastrophes worse. This is an essential issue for every element of corporate strategy, from supply chain issues to core operations and risk management.”

- A study published in Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal by Michael Magnan and Hani Tadros found that better disclosure of environmental performance correlated with better performance at the 78 companies in environmentally sensitive industries that they examined.

In this paper, we aim to bridge the gap in the literature about the association between environmental disclosure and environmental performance by analyzing the motivation of firms with high or low environmental performance to disclose proprietary environmental information that could compromise the firm’s competitive position or have direct impact on its cash flow. Consistent with some prior research, we argue that economic- and legitimacy-based incentives both drive a firm’s environmental disclosure. However, revisiting prior research, we put forward the view that a firm’s environmental performance (either high or low) moderates the effects of these incentives on environmental disclosure in a differential fashion.

Of course, you do not have to be an economist to conclude that companies will be more transparent when there is good news to report. What matters here is what investors can conclude from the level of transparency in these disclosures, and what it means about the potential— or necessity— for engagement. We point the Commission to the work of Tensie Whelan of NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business on ESG data as a key indicator of supply chain risk, and to ESG Shareholder Engagement and Downside Risk by Andreas G.F. Hoepner, Ioannis Oikonomou, Zacharias Sautner, Laura T. Starks, and Xiao Y. Zhou, which found that investor engagement on ESG issues can significantly reduce investment risk.

- The Bank of England takes note of climate-related investment risk:

[A] speech by Sarah Breeden, head of international banks supervision, suggests…that time is running out to prevent catastrophic climate change and previous efforts to combat the problem have been nowhere near vigorous enough.

Breeden’s message to the financial sector was that they need to incorporate climate change into their corporate governance, their risk management analysis, their forward planning and their disclosure policies or face the prospect of losing a heck of a lot of money.

The financial markets have a term for a sudden drop in assets prices known as a Minsky moment (after the economist Hyman Minsky). Breeden said a climate Minsky moment was possible, in which losses could be as high as $20tn (£15.3tn).

If the Bank of England is calling on companies to address the risks of climate change, then the Commission should recognize that investors need this information to assess investment risk.

- A July 2020 report from GAO documents the financial/”pecuniary” priority of institutional investors use of ESG factors in calculating investment risk. We incorporate that entire report by reference in this document. An excerpt:

Institutional investors with whom we spoke generally agreed that ESG issues can have a substantial effect on a company’s long-term financial performance. All seven private asset managers and representatives at five of seven public pension funds said they seek ESG information to enhance their understanding of risks that could affect companies’ value over time. Representatives at the other two pension funds said that they generally do not consider ESG information relevant to assessing companies’ financial performance. While investors with whom we spoke primarily used ESG information to assess companies’ long-term value, other investors also use ESG information to promote social goals. A 2018 US SIF survey found that private asset managers and other investors, representing over $3.1 trillion (of the $46.6 trillion in total U.S. assets under professional management), said they consider ESG issues as part of their mission or in order to produce benefits for society….

These investors added that they use ESG disclosures to monitor companies’ management of ESG risks, inform their vote at shareholder meetings, or make stock purchasing decisions. Most of these institutional investors noted that they seek additional ESG disclosures to address gaps and inconsistencies in companies’ disclosures that limit their usefulness. [emphasis added, footnotes omitted]

GAO has done the kind of thorough analysis that can be helpful to the Commission in understanding the way investors are looking at ESG factors. And what we learn is that not one of the investors surveyed made any “pecuniary” trade-offs and the overwhelming majority look at ESG exclusively in financial terms.

- Pensions and Investments reported on an ISS study:

A link exists between a company’s ESG performance and its financial performance, according to a study published from ISS ESG, the responsible investment arm of Institutional Shareholder Services.

Firms with high or favorable ISS ESG corporate ratings tend to be more profitable through an economic value-added lens, the study found.

“While one can argue that the relationship between ESG and financial performance is perhaps due to the fact that more profitable firms have the resources to invest in areas that positively influence ESG, it could also be that profitability rises as a result of a company better managing its material ESG risks, or it could be a little bit of both,” the study said. “If it is a little bit of both, then this means that good-ESG initiatives drive up financial performance, which then provides the monetary resources to invest to be an even better ESG firm, which then drives up performance again, and so on.”

Moreover, companies with better ESG ratings are also less volatile, noted Anthony Campagna, global head of fundamental research at ISS EVA.

- A January 2021 report produced by the United Nations in collaboration with 22 major insurance firms found that the insurance industry needs to adopt an integrated approach in order to manage future climate change risk. The report is making a “ground-breaking, yet still preliminary” effort to develop a methodology to assess climate-change related litigation risk, encompassing potential costs, fines and penalties, prosecutions of executives, impacts on valuation and credit ratings, policyholder claims and exclusions between the insured and insurer.

As society’s early warning system, the insurance industry has the unique opportunity to become its global navigation system—an industry that will help society manage the risks of today, navigate the risk landscape of tomorrow, and reap the opportunities along the way.

A few responses to a few of the comments already submitted, with thanks to Tulane professor Ann M. Lipton for highlighting some of these issues:

- There is no possible definition of “solicitation” that can be stretched and distorted to include independent evaluations voluntarily purchased or obtained by investors and therefore no possible reason to include ESG ratings or analyses within the regulatory restrictions imposed on firms hired as advocates. The reason for regulation of solicitors is that they are paid by corporate insiders to make the best case for one side, and therefore not objective. Providers of research and analysis purchased (or not) by financial professionals are market-tested. But ESG claims made by financial professionals to investors, like solicitations, are likely to be self-serving and may require some standard-setting.

- The suggestion that ESG policies be included with codes of ethics (see comment of Morrison Foerster) seems to be just a way of making sure that investors will have no meaningful oversight or response as failure to follow the code is not necessarily disclosed or actionable.

- Obviously, the comments that attempt to remind the Commission that any guidance or regulation on ESG should depend on materiality are creating a straw man. Commenters in favor of ESG disclosures may differ in their ideas of what is material, which is the reason for undertaking this inquiry, and that includes portfolio-based materiality. But no one is asking for disclosures that are anything but vitally financially material to investment risk and return.

- Many of the industry comments recognize that they can no longer pretend that some kind of ESG is not inevitable, so they begin with assertions that they are on board then quickly move to suggest approaches that undermine any meaningful disclosure, most often a “go slowly and trust us” or “furnished rather than filed” approach that will make it impossible to get reliable and consistent data. While we support a first step that allows for some flexibility and innovation (see below), we hope the Commission will be cautious in evaluating comments with rhetoric that obscures efforts to, well, obscure climate and ESG risks.

- There are still a few holdouts who put quotation marks around climate “risk” to show that they are not yet willing to accept that such a thing is real. That has led to some self-owns, as when the National Mining Association admitted that what they fear from climate risk disclosures is that the information will make them look like a less attractive investment. (“NMA is concerned that mandatory disclosure rules—particularly related to non-material climate-related risks—could proliferate investment bias and practices by investors and financial institutions to exclude certain energy-intensive companies and sectors from investment portfolios or restrict access to or significantly increase the cost of capital.” Needless to say, they provide no evidence or examples to show that “non-material” climate risk indicators exist.) This is, of course, the actual purpose of disclosure and the meaning of materiality. Indeed, to keep this information from investors is to give these companies a government-authorized subsidy that is contrary to efficient markets and capital formation. In summary, investors are in a far better and less conflicted position to determine what is material to their evaluation of investment risk and return than issuers or service providers.

Next steps:

The consensus on the need for ESG and climate change disclosures is ahead of anyone’s capacity to provide them. For that reason, I recommend that the Commission approach this question in stages, coordinating with international groups to promote consistent standards while continuing to keep the United States as the most comprehensively transparent capital markets in the world. The first stage should have two goals: encouraging innovation and transparency of process, with a “comply or explain” approach whenever possible. Ideally, I’d like to see some move toward widespread adoption of SASB disclosures within five years in an XBRL format (we reiterate our plea for XBRL reporting of proxy votes by fund managers), unless the issuer explains why a different approach is better for their company. But even I would not support guidance or rulemaking along those lines without further study, beginning with hearings so that we can better understand the strengths and weaknesses of current ESG reporting and ratings.

In the meantime, guidance on disclosure should focus on clarity about how each reporting entity defines ESG, with care to avoid the problem of boilerplate, near-identical disclosures as we now have in the CD&A language from board compensation committees. The Commission can be helpful here by releasing a list of sample questions that each company should answer, including: Which board committee is responsible for evaluating ESG risk? What does the board consider its primary ESG vulnerabilities and opportunities and what steps are they taking to address them? What ESG priorities are reflected in the incentive compensation of the top executives? How is the company preparing for the prospect of regulatory changes from agencies other than the SEC, for example the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the Department of Transportation, OSHA, the FTC, and EPA? How about regulatory changes from the EU or other trading partners?

Disclosure of any ESG related campaign contributions and lobbying expenditures, direct or indirect, should be a top priority for guidance. The recent release of recordings by Keith McCoy, senior director of ExxonMobil for federal relations makes absolutely clear the gulf between what some companies tell their customers and investors and what they advocate and support with undisclosed campaign contributions and lobbying. This kind of material misdirection and outright misrepresentation is made possible by lack of transparency.

I concur with the comments asking that private companies and investment managers should be covered as well.

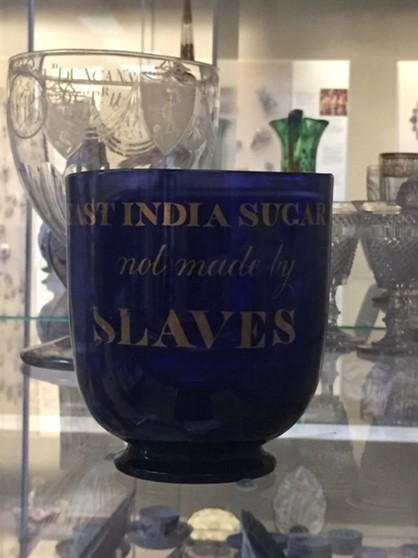

I conclude with a reminder that ESG is not new. I took this photograph of a jar from the early 19th century in the British Museum.

The ESG disclosure from the East India Sugar Company is larger than the name of the company or the identification of the product. It was produced in a time of the first major consumer boycotts, which would lead to the abolition of slavery in England decades before it took a war to abolish it in the US. Today’s investors and consumers are continuing in a tradition that goes back to the earliest days of capitalism. It is now up to the Commission to make sure the ESG disclosures investors need are as accurate and reliable as materiality requires.

Endnotes

1Every major financial institution and every significant institutional investor now has one or more ESG options. US ESG index funds reached over $250 billion in 2020. More significantly, ESG factors are permeating every aspect of even the most traditional investment vehicles. A 2020 survey of 809 institutional asset owners, investment consultants and financial advisers found that 75 percent of them use ESG factors in their investment strategies, up from 70 percent in 2019. Nearly 13 percent of respondents were pension plan sponsors. The largest institutional investor in the US is Black Rock, which has announced that 100 percent of its approximately 5,600 active and advisory BlackRock strategies are ESG integrated— covering U.S. $2.7 trillion in assets. Reflecting the demand, BlackRock introduced 93 new sustainable solutions in 2020, helping clients allocate U.S. $39 billion to sustainable investment strategies, which helped increase sustainable assets by 41 percent from December 31, 2019.(go back)

2https://www.forbes.com/sites/palashghosh/2021/03/24/gun-sales-are-soaring-so-why-are-gun-stocks-languishing/?sh=48b709f72f8f(go back)

3On July 1, 2020, the U.S. Department of State, along with the U.S. Department of the Treasury, the U.S. Department of Commerce, and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, issued a Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory (Business Advisory) to caution businesses about the risks of supply chain links to Chinese entities that engage in human rights abuses, including forced labor, in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang) and elsewhere in China.(go back)

4Detailed new guidance on ESG from the EU. makes clear that any effort to limit investor access to ESG in evaluating risk and return will put US investors and issuers at a serious disadvantage in global markets if we do not do as well or better.(go back)

5https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/30/climate/exxon-greenpeace-lobbyist-video.html(go back)

Comment on Climate Disclosure

More from: Nell Minow, ValueEdge Advisors

Nell Minow is Vice Chair of ValueEdge Advisors. This post is based on her comment letter to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here); For Whom Corporate Leaders Bargain by Lucian A. Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel, and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here); Socially Responsible Firms by Alan Ferrell, Hao Liang, and Luc Renneboog (discussed on the Forum here); and Restoration: The Role Stakeholder Governance Must Play in Recreating a Fair and Sustainable American Economy—A Reply to Professor Rock by Leo E. Strine, Jr. (discussed on the Forum here).

The accountability processes of government and business are each ideal for optimizing different policy issues, and we get into trouble when we let one take on the role of the other. What has made the US capital markets the most robust and respected in the world is the combination of market- and government-based structures and especially the comprehensive transparency of our public companies. The nature of capitalism is to maximize profits, and it is up to the government to make sure that happens without externalizing costs onto the public who have no capacity to provide a market-based response. Corporate executives would always prefer less disclosure. Investors would prefer more. Because of the collective choice problem, there is no way for investors to make a market-based demand for more information as effectively and efficiently as having the government set the floor for what must be disclosed.

It is within this context that the questions will always arise about when it is time to add more to the already extensive information that issuers must provide to investors. As the request for comments and Commissioner Lee’s outstanding presentation on materiality suggest, that time has come for ESG. The reason it is the fastest-growing sector of investment vehicles [1] is a reflection of increasing concerns about the inadequacy of GAAP numbers in assessing investment risk. Let me emphasize that; ESG and climate change disclosure concerns are entirely and exclusively financial. That is what makes them a have-to-have, not a nice-to-have.

This is not surprising. After more than a century of working with GAAP, there is still a lot of inconsistency in the way accounting rules are applied. GAAP may allow for a lot of options in disclosing the value of factory equipment, but at the end of the process, hard assets are something you can count and the tax code is helpful, too, in validating those numbers. And GAAP is based on data that corporations are already required to disclose in fairly consistent apples-to-apples form. ESG, which is a recent response to the inadequacy of GAAP in assessing investment risk, is still in its earliest stages. ESG factors are inadequately and inconsistently disclosed and harder to quantify. Even so, they are already vitally important in providing guidance that traditional GAAP cannot. GAAP is focused on what values are today. ESG is about evaluating the risks of tomorrow and five and ten years from now.

There is one thing ESG is unequivocally not: non-financial. Imperfect and inconsistent as ESG data are, they are entirely and exclusively methods for better assessing investment risk and return. The comments that claim otherwise, like those of the fossil fuel companies, have failed to provide a single example to prove that there is any trade-off in shareholder value. And when it comes to what shareholders need, the Commission should rely more on what investors say they need than what issuers would prefer to give them. As a matter of law and economics, investors have the fewest conflicts of interest in determining what they need to make a buy/hold/sell decision.

ESG is focused on factors that will affect the enterprise as a sustainable concern. Black Rock, for example, announced that it has added 1200 “sustainability metrics” to its calculus in 2020. The UK’s Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) was created by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to develop consistent climate-related financial risk disclosures for use by companies, banks, and investors in providing information to stakeholders. In the US, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) is merging with the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) to provide investors and companies a comprehensive corporate reporting framework to drive global sustainability performance.

Admittedly, there is no consensus and a lot of inconsistency in defining what ESG is, which is another reason to be grateful for the Commission’s involvement. The interest in ESG is far ahead of the capacity to assess or evaluate it. And, as with any topic that has reached the tipping point, a lot of people and organizations are slapping ESG labels on themselves to get a piece of the action, all the more reason for additional guidance from the Commission.

I have a brokerage account. The online interface now includes what they call an “ESG” analysis and a separate “impact analysis” tied to goals like ethical leadership and racial equality. It is not clear what data or which data providers are used for these assessments. There are ads on television now for “ESG-neutral” investment 2ndVote Funds. “ESG-neutral” is a meaningless term. The offerings include pro-gun and anti-abortion ETF filters that can only be categorized as Social. These are unquestionably ESG funds; the managers just assign different weights to the ESG factors than funds based on analysis that gun stocks, for example, may be a sub-optimal investment. [2] That is fine, of course. Just as some portfolio managers may be buying a stock as others, even in the same organization, are selling it. What is important is making sure that investors have a clear idea of what factors and investment goals are the basis for those decisions. I note that despite repeated requests, 2ndVote has not provided me with their proxy voting policies or records of past votes, but it is likely that ESG analysis is involved in at least some of those votes. I look forward to reviewing their N-PX forms.

All of this further shows why we need clearer, more consistent information. When consumers demanded organic foods, government standard-setting was the only way to make sure that term was used only when it meets some consistent and supportable standard. That is where we are with ESG. The exponential increase in the use of ESG and related terms in investment and corporate communications makes it an urgent priority for guidance from the Commission to prevent misleading or confusing investors.

E, S, and G

We sometimes forget that E, S, and G are three very different categories, with very different levels of consensus and understanding about them.

For example, look at one small part of the almost catch-all category, S, for Social. The annual reports that accompany proxy statements almost always claim that the company’s greatest asset is its people. But GAAP tells us almost nothing about how to assess their value. How many PhDs? How many economists/MBAs/programmers/sales representatives? What incentives are provided for worker education and promotion? How is diversity supported by management? Other questions that might fall into the S of ESG could pertain to whistleblower protection, supply chain issues like the ones highlighted in the July 7, 2020 statement issued by four cabinet agencies, [3] cybersecurity, and the increasingly controversial issue of political contributions. Or the possibility of a pandemic, a risk only a small fraction of issuers were prepared for in 2020.

The E can be misleading. Companies that have to disclose problems, violations, and fines may appear higher-risk than those that have not (yet) been the subject of investigations. As some of the commenters have already said, it is important that the E not be limited to a company’s carbon footprint. Every company has environmental risk, whether it is the direct result of operations or products, as in the fossil fuel industry, or the impact of climate change on supply chains, coastal properties, or insurance.

There is more consensus at the moment around the G factors. Many are thoroughly covered by state law and current SEC disclosure rules, like those pertaining to executive compensation, related party transactions, board member stock ownership and meeting attendance. I find, though, that the best way to judge governance effectiveness is to look at the results, rather than the policies, and “resume independence” does not always translate to more effective oversight. So, some improvement there might also be called for.

In all three categories, the Commission must make sure the focus is on what counts, not just what can be counted.

Evidence about the increasing sophistication of institutional investors in using ESG indicators to evaluate risk and return and the increasing importance of those factors:

Just a few examples:

Of course, you do not have to be an economist to conclude that companies will be more transparent when there is good news to report. What matters here is what investors can conclude from the level of transparency in these disclosures, and what it means about the potential— or necessity— for engagement. We point the Commission to the work of Tensie Whelan of NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business on ESG data as a key indicator of supply chain risk, and to ESG Shareholder Engagement and Downside Risk by Andreas G.F. Hoepner, Ioannis Oikonomou, Zacharias Sautner, Laura T. Starks, and Xiao Y. Zhou, which found that investor engagement on ESG issues can significantly reduce investment risk.

If the Bank of England is calling on companies to address the risks of climate change, then the Commission should recognize that investors need this information to assess investment risk.

GAO has done the kind of thorough analysis that can be helpful to the Commission in understanding the way investors are looking at ESG factors. And what we learn is that not one of the investors surveyed made any “pecuniary” trade-offs and the overwhelming majority look at ESG exclusively in financial terms.

A link exists between a company’s ESG performance and its financial performance, according to a study published from ISS ESG, the responsible investment arm of Institutional Shareholder Services.

Moreover, companies with better ESG ratings are also less volatile, noted Anthony Campagna, global head of fundamental research at ISS EVA.

A few responses to a few of the comments already submitted, with thanks to Tulane professor Ann M. Lipton for highlighting some of these issues:

Next steps:

The consensus on the need for ESG and climate change disclosures is ahead of anyone’s capacity to provide them. For that reason, I recommend that the Commission approach this question in stages, coordinating with international groups to promote consistent standards while continuing to keep the United States as the most comprehensively transparent capital markets in the world. The first stage should have two goals: encouraging innovation and transparency of process, with a “comply or explain” approach whenever possible. Ideally, I’d like to see some move toward widespread adoption of SASB disclosures within five years in an XBRL format (we reiterate our plea for XBRL reporting of proxy votes by fund managers), unless the issuer explains why a different approach is better for their company. But even I would not support guidance or rulemaking along those lines without further study, beginning with hearings so that we can better understand the strengths and weaknesses of current ESG reporting and ratings.

In the meantime, guidance on disclosure should focus on clarity about how each reporting entity defines ESG, with care to avoid the problem of boilerplate, near-identical disclosures as we now have in the CD&A language from board compensation committees. The Commission can be helpful here by releasing a list of sample questions that each company should answer, including: Which board committee is responsible for evaluating ESG risk? What does the board consider its primary ESG vulnerabilities and opportunities and what steps are they taking to address them? What ESG priorities are reflected in the incentive compensation of the top executives? How is the company preparing for the prospect of regulatory changes from agencies other than the SEC, for example the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the Department of Transportation, OSHA, the FTC, and EPA? How about regulatory changes from the EU or other trading partners? [4]

Disclosure of any ESG related campaign contributions and lobbying expenditures, direct or indirect, should be a top priority for guidance. The recent release of recordings by Keith McCoy, senior director of ExxonMobil for federal relations [5] makes absolutely clear the gulf between what some companies tell their customers and investors and what they advocate and support with undisclosed campaign contributions and lobbying. This kind of material misdirection and outright misrepresentation is made possible by lack of transparency.

I concur with the comments asking that private companies and investment managers should be covered as well.

I conclude with a reminder that ESG is not new. I took this photograph of a jar from the early 19th century in the British Museum.

The ESG disclosure from the East India Sugar Company is larger than the name of the company or the identification of the product. It was produced in a time of the first major consumer boycotts, which would lead to the abolition of slavery in England decades before it took a war to abolish it in the US. Today’s investors and consumers are continuing in a tradition that goes back to the earliest days of capitalism. It is now up to the Commission to make sure the ESG disclosures investors need are as accurate and reliable as materiality requires.

Endnotes

1Every major financial institution and every significant institutional investor now has one or more ESG options. US ESG index funds reached over $250 billion in 2020. More significantly, ESG factors are permeating every aspect of even the most traditional investment vehicles. A 2020 survey of 809 institutional asset owners, investment consultants and financial advisers found that 75 percent of them use ESG factors in their investment strategies, up from 70 percent in 2019. Nearly 13 percent of respondents were pension plan sponsors. The largest institutional investor in the US is Black Rock, which has announced that 100 percent of its approximately 5,600 active and advisory BlackRock strategies are ESG integrated— covering U.S. $2.7 trillion in assets. Reflecting the demand, BlackRock introduced 93 new sustainable solutions in 2020, helping clients allocate U.S. $39 billion to sustainable investment strategies, which helped increase sustainable assets by 41 percent from December 31, 2019.(go back)

2https://www.forbes.com/sites/palashghosh/2021/03/24/gun-sales-are-soaring-so-why-are-gun-stocks-languishing/?sh=48b709f72f8f(go back)

3On July 1, 2020, the U.S. Department of State, along with the U.S. Department of the Treasury, the U.S. Department of Commerce, and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, issued a Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory (Business Advisory) to caution businesses about the risks of supply chain links to Chinese entities that engage in human rights abuses, including forced labor, in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang) and elsewhere in China.(go back)

4Detailed new guidance on ESG from the EU. makes clear that any effort to limit investor access to ESG in evaluating risk and return will put US investors and issuers at a serious disadvantage in global markets if we do not do as well or better.(go back)

5https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/30/climate/exxon-greenpeace-lobbyist-video.html(go back)