Audra Cohen and Melissa Sawyer are partners at Sullivan & Cromwell LLP. This post is based on a Sullivan & Cromwell memorandum by Ms. Cohen, Ms. Sawyer, Eric Krautheimer, and Matthew Goodman.

Executive Summary

Many investors take into account corporate governance in their investment decisions. Retail companies are generally in-line with the governance norms of companies across the S&P 500, although differences exist in corporate governance trends between brick-and-mortar retail companies and e-commerce retail companies. For example, e-commerce retailers have greater rates of board refreshment and are more likely to separate the roles of CEO and chair than their brick-and mortar counterparts. Furthermore, e-commerce retailers are more likely to permit shareholders to act via written consent and are less likely to permit shareholders to call a special meeting.

Retail companies should consider what governance practices work best for their particular products, customer base, board composition, investor base and strategic objectives. Analyzing broader industry trends can be helpful, but companies should determine their practices based on conversations with directors, investors and key stakeholders. [1]

For purposes of our analyses, we reviewed the corporate governance practices of the 14 retail companies identified in Annex A (the “Retail Companies”). Of those Retail Companies, nine are historically brick-and-mortar companies (the “Brick-and-Mortar Retailers”) and five are historically e-commerce companies (the “E-Commerce Retailers”). However, it should be noted that the line between brick-and-mortar companies and e-commerce companies is becoming increasingly blurred, as brick-and-mortar companies continue to expand into the e-commerce space and vice versa.

I. Trends in Board Composition

A. Board Refreshment

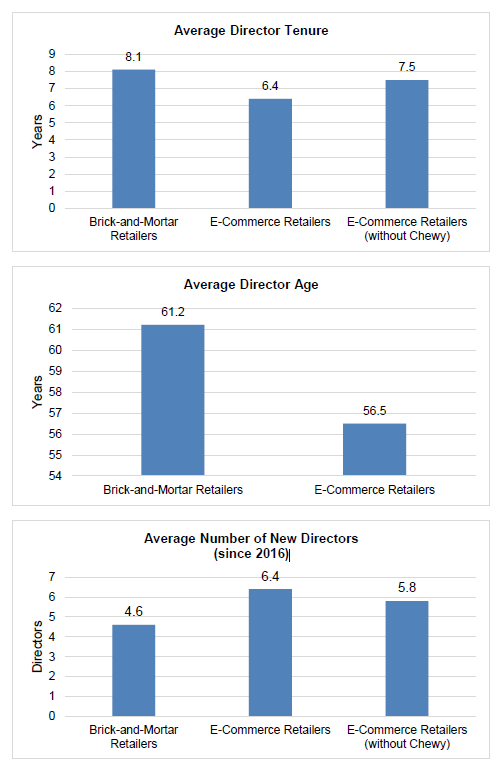

Retail Companies have an average director tenure of about 7.5 years (7.9 years excluding Chewy, [2] which has been public for less than two years), which is largely consistent with the average director tenure of 7.9 years for S&P 500 companies. [3]

The institution of a specified retirement age is the most common board refreshment policy among the Retail Companies sampled. However, while 67% of the Brick-and-Mortar Retailers have implemented a specified retirement age, no E-Commerce Retailer has followed suit. Two Brick-and-Mortar Retailers also instituted term limits in conjunction with a mandatory retirement age of 72.

While none of the E-Commerce Retailers have a specific retirement age or term limit, the E-Commerce Retailers on average have added more new directors in the last five years (6.4 directors, or 5.8 directors excluding Chewy) than the Brick-and-Mortar Retailers (4.6 directors). [4] Similarly, the average director tenure amongst the E-Commerce Retailers is slightly lower at approximately 6.4 years compared to 8.1 years for Brick-and-Mortar Retailers. This lower average tenure of the E-Commerce Retailers may be attributable, in part, to the fact that many of the E-Commerce Retailers sampled completed their initial public offerings relatively recently—the average director tenure for each of Wayfair, Chewy and Etsy is roughly equal to the number of years the companies have been public. For the recently IPO’d E-Commerce Retailers, a better measure of board refreshment may be the number of new directors they have added to their boards since their IPOs. Using this framework, E-Commerce Retailers add slightly fewer directors per year (0.82 directors) than Brick-and-Mortar Retailers (0.91 directors).

Directors at the E-Commerce Retailers tend to be younger than directors at Brick-and-Mortar Retailers—the directors at the E-Commerce Retailers average approximately 56.5 years of age, whereas directors at Brick-and-Mortar Retailers average approximately 61.2 years of age. In comparison, the average age of directors in S&P 500 companies overall is 63.4 years, which exceeds the average age of directors at both the E-Commerce and Brick-and-Mortar Retailers.

B. Board Evaluation

All Retail Companies conduct annual board evaluations and director self-evaluations overseen by their respective governance committees. With the exception of Chewy, all Retail Companies have a lead independent director that is appointed annually when the board chair is not an independent director, and this lead independent director is often involved with the evaluation process. Chewy currently separates its CEO and board chair positions, though it does not expressly require a lead independent director when the board chair is not independent. Three Brick-and-Mortar Retailers also noted in their proxy statements that they periodically engage a third-party consulting firm to lead the evaluation process and provide independent assessments of board and director performance, while no E-Commerce Retailers noted the same.

C. Board Expertise

The Retail Companies tend to prioritize retail or merchandise experience in their directors, with over half of the Retail Companies reporting that five or more directors bring retail experience to the board. E-commerce or technology experience is also prevalent on the Retail Company boards, even amongst the Brick-and-Mortar Retailers. Over half of the Brick-and-Mortar Retailers and three of the five E-Commerce Retailers reported having at least three board members with experience in e-commerce or technology.

Three of the Retail Companies also have board members with media experience. Amazon, which produces its own media content for streaming customers, has a director with experience in television and content creation. Walmart and Wayfair also each have one director with media experience.

D. CEO/Chair Structure

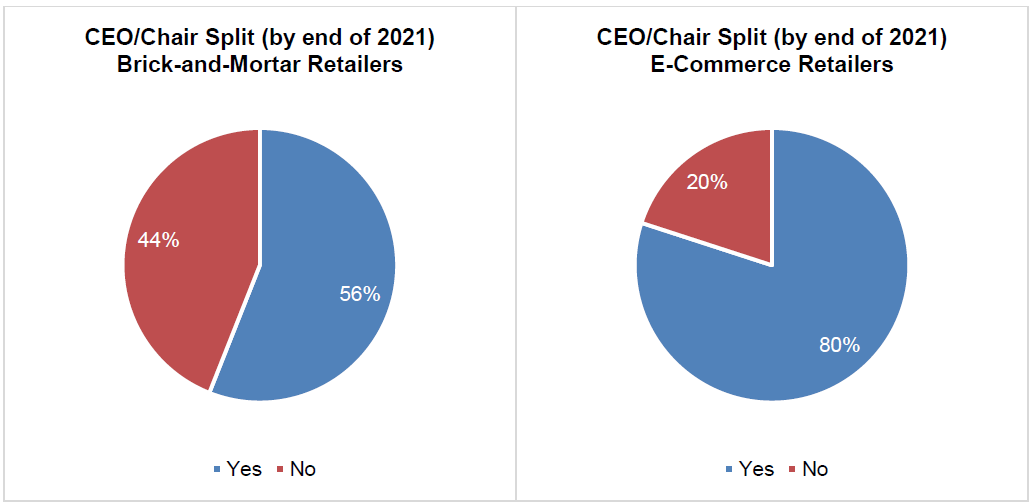

The Retail Companies increasingly follow the trend among S&P 500 companies of separating the CEO and board chair positions. According to Spencer Stuart, in 2020, 55% of S&P 500 boards have split the two positions, which is an increase from 40% of boards in 2010. [5] Nine of the Retail Companies surveyed out of 14 currently have a CEO/chair split. However, Brick-and-Mortar Retailers are less likely than E-Commerce Retailers to separate the CEO and board chair positions. Some institutional investors take the position that a separation in the positions allows for better independent decision-making by the board. The five Retail Companies that do not have a CEO/chair split have a lead independent director, in addition to the board chair, which can help alleviate these concerns. Three of the Retail Companies have an Executive Chair who is a former or current officer of the company. Due to the Executive Chair’s non-independent status, the relevant boards have also elected an independent lead director.

While nine of the Retail Companies currently have a CEO/chair split, every company sampled except for Walmart explicitly maintains flexibility to combine the CEO/chair role in the future by not having a strict policy on separating the positions. These companies, with the exception of Chewy, also specify that the board will select a lead independent director in the event that the CEO serves as chair.

Finally, all of the Retail Companies surveyed have a single person serving in the role of chair, except for Wayfair. The two co-founders of Wayfair, one of whom serves as the CEO, are co-chairs of the board.

E. Number of Board Meetings

Retail Company boards generally disclosed fewer meetings than the average S&P 500 company board in 2020. In 2020, S&P 500 boards disclosed they met an average of 7.9 times, while Retail Company boards disclosed they met an average of 6.9 times, excluding Home Depot. [6] Only Home Depot explicitly reported a significant increase in the number of formal board meetings in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, with the board meeting 18 times in 2020 instead of the company’s normal five. Excluding Home Depot, the boards of Brick-and-Mortar Retailers disclosed they met an average of 6.1 times in 2020, which is slightly less than the average of seven times the boards of E-Commerce Retailers disclosed they met in 2020.

II. Trends in Committee Structure and Membership

A. Number of Committees

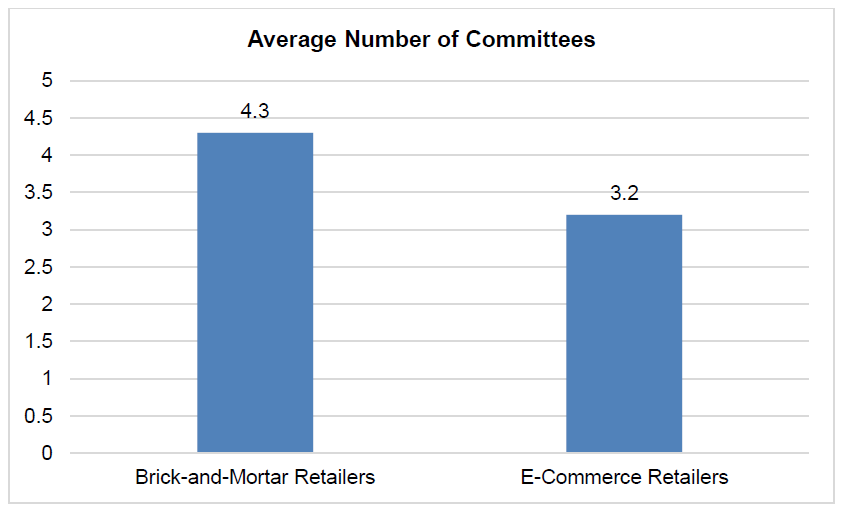

Pursuant to stock exchange rules, public companies must have audit, compensation, and governance standing committees. [7] All of the Retail Companies have these three committees, but some also have additional committees. On average, Retail Companies have four committees, which aligns with the S&P 500 average of 4.2 committees. However, Brick-and-Mortar Retailers have more committees on average than E-Commerce Retailers. For example, two Brick-and-Mortar Retailers have additional e-commerce or technology committees, whereas other Retail Companies delegate responsibility for technology or e-commerce issues to their audit or risk compliance committees. One Brick-and-Mortar Retailer, Lowe’s, also has a separate sustainability committee, and another, Kroger, has a separate public responsibilities committee governing corporate responsibility. Target also has an infrastructure and investment committee and a separate risk and compliance committee. Comparatively, all E-Commerce Retailers sampled have only three standing committees, with the exception of eBay, which has an additional committee governing risk.

III. Trends in Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (“DEI”)

A. Board Diversity [8]

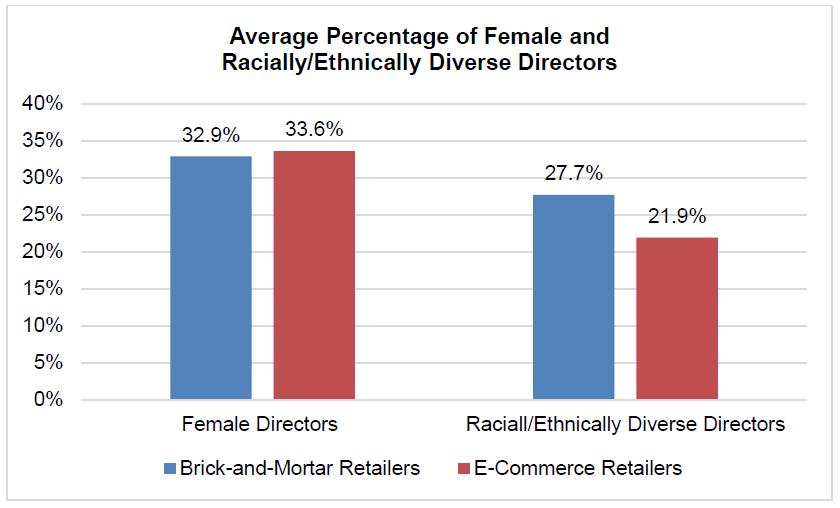

The Retail Companies have a higher percentage of female directors relative to the S&P 500 average. According to Spencer Stuart, 28% of S&P 500 directors were women in 2020. [9] Amongst the Retail Companies, women make up 34.2% of directors. Women hold anywhere from 25% to 50% of each Retail Company’s board seats. Furthermore, every Retail Company explicitly discloses the number of female directors in its annual report. There does not appear to be a significant difference between the percentage of female directors on Brick-and-Mortar Retailer boards (32.9% female directors on average) and E-Commerce Retailer boards (33.6% female directors on average).

Most Retail Companies did not explicitly report how many committee chair positions are held by women. However, the majority of the Retail Companies have at least one woman serving as a committee chair. [10] While women have a strong presence on the Retail Company boards, only one woman serves in a board chair position.

Similarly, all but one Retail Company board explicitly reported the number of ethnically diverse directors in their proxy statements. Ethnically diverse directors make up approximately 25.4% of Retail Company boards that report the statistic, which is slightly higher than the S&P 500 average of 20% in 2020. [11] The E-Commerce Retailers on average have less racial/ethnic diversity on their boards with an average of 16.1% racially/ethnically diverse directors, while Brick-and-Mortar Retailers have an average of 28.2% racially/ethnically diverse directors. Only two of the Retail Companies disclosed the number of self-reported LGBTQ+ directors. One Retail Company, Etsy, also reports that one director self-identifies as disabled.

Of the Retail Companies sampled that are subject to various diversity requirements imposed by stock exchanges or state laws, all fulfilled these requirements. For example, all five Retail Companies listed on the NASDAQ Stock Exchange complied with NASDAQ’s requirement for a certain minimum number of diverse directors. [12]

B. DEI Policies and Programs

Twelve of the 14 Retail Companies publish information about their DEI programs on their websites. Many Retail Companies offer formal programming to foster diversity. These initiatives include affinity groups for employees, free educational programming and implicit bias training for managers.

Some of the Retail Companies have adopted so-called “Rooney Rule” policies, which at the board level require that the board consider female or ethnically diverse candidates. Three Retail Companies (two E-Commerce Retailers and one Brick-and-Mortar retailer) apply this rule only to director candidate pools, while one Brick-and-Mortar Retailer also expands the requirements to salaried leadership positions.

C. Diversity Statistics

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 requires companies with 100 or more employees to submit an EEO-1 report annually. The report consists of demographic data about the race/ethnicity and sex of employees who serve in different job positions at the company. [13]

Currently, only three of the Retail Companies (two Brick-and-Mortar Retailers and one E-Commerce Retailer) have released annual EEO-1 data, and one additional Brick-and-Mortar Retailer has committed to start reporting the data in 2021. While the percentage of Retail Companies currently committed to releasing EEO-1 information is low, there is likely to be a large shift in this industry trend in the near future. In the 2021 proxy season, there were 42 shareholder proposals submitted relating to EEO-1 reporting and EEO policies compared to only 15 proposals in 2020. [14] Furthermore, the average percentage of shareholder votes cast in favor of such proposals drastically increased by nearly three-fold, from an average of 25% in 2020 to an average of 70% in 2021. [15] In 2020, State Street also sent a letter to board chairs calling for the disclosure of EEO-1 data. [16] Similarly, in 2021, the New York State Comptroller filed shareholder proposals about the disclosure of the data. [17]

Only three of the Retail Companies disclose data on gender pay equity (two E-Commerce Retailers and one Brick-and-Mortar Retailer). Of the Retail Companies that do report the data, women on average earned at least 99.9% of what men are paid in the U.S., and 99.7% of what men are paid globally. Only Amazon released racial pay equity statistics, reporting that minority employees on average earned 99.2 cents for every dollar that white employees earned in 2020.

IV. Trends in Shareholder Rights

A. Special Meeting Rights

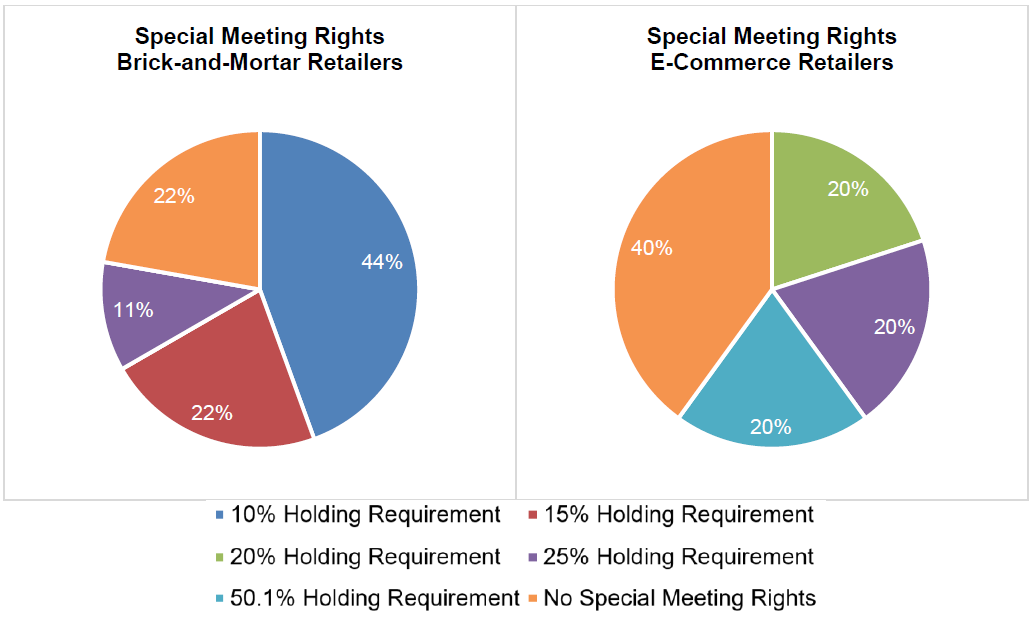

Most of the Retail Companies allow shareholders to call special meetings. However, there is a lot of variability in the implementation of this right. Four of the Retail Companies allow shareholders holding 10% of the company’s stock to request a special meeting. Other Retail Companies providing for this right, however, require higher holding thresholds in order to call a special meeting, ranging from 15% to 50.1%. The E-Commerce Retailers are more likely to take a more restrictive approach to special meeting rights by either not granting the right at all (Etsy and Wayfair), or setting a higher holding threshold of at least 20% (20% for eBay, 25% for Amazon, and 50.1% for Chewy).

B. Written Consent Rights

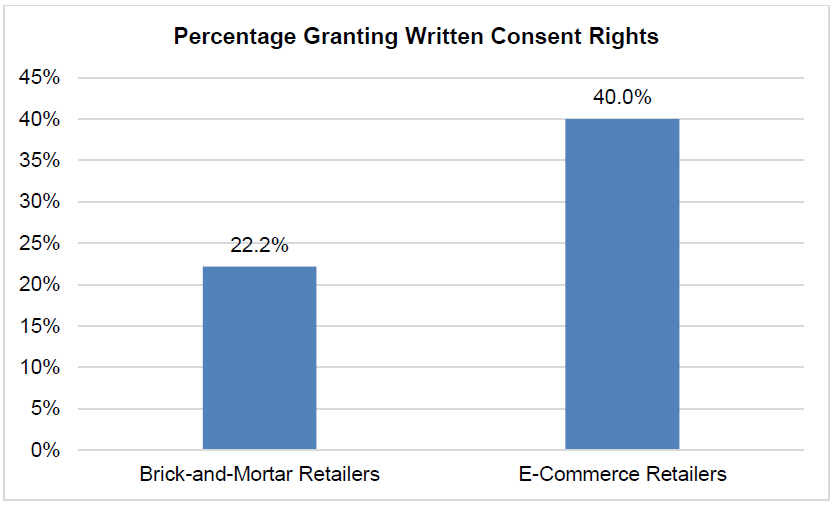

Action by written consent allows shareholders to act outside of a formal shareholder meeting. Only four of the Retail Companies—two E-Commerce Retailers and two Brick-and-Mortar Retailers, or 40% of the E-Commerce Retailers and 22.2% of the Brick-and-Mortar Retailers—provide such a right. These four companies have a shareholder-friendly written consent formulation that only requires over 50% consent, consistent with 29.4% of S&P 500 companies. [18] All of the other Retail Companies explicitly prohibit action by written consent.

C. Proxy Access

Proxy access allows shareholders to include shareholder director nominees on the company’s proxy card. All of the Brick-and-Mortar Retailers grant shareholders this right, which exceeds the S&P 500 average of 81.6%. [19] Comparatively, the E-Commerce Retailers appear less likely to allow proxy access, with only two of the five E-Commerce Retailers granting the right to shareholders. Furthermore, all of the Retail Companies that allow proxy access have the same basic requirements in place—a 3% holding requirement for three years. Shareholders that meet these holding requirements can nominate up to the greater of two individuals or 20% of the board.

D. Voting for Directors

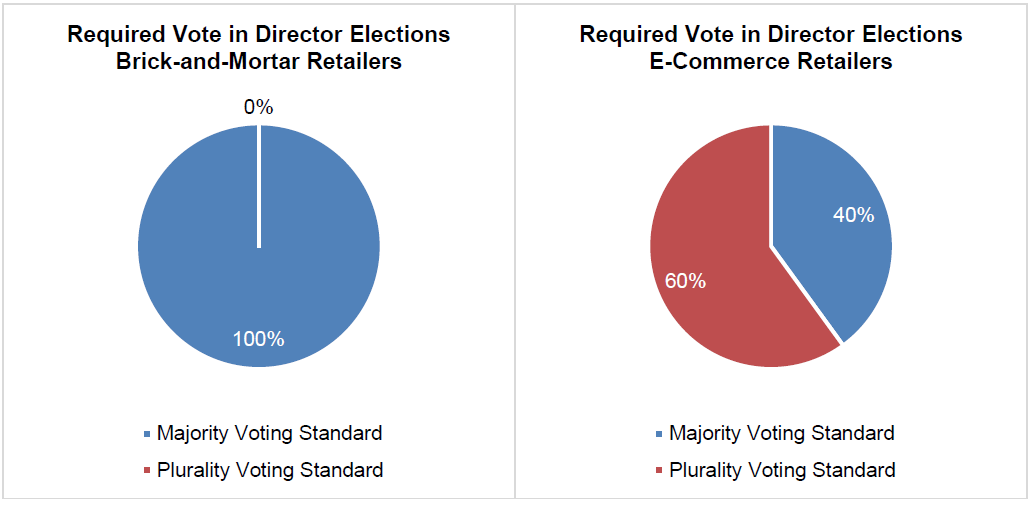

The Retail Companies have followed the trend of S&P 500 companies shifting to a majority voting standard in the election of directors in uncontested elections. [20] Proponents argue that majority voting creates better board accountability to shareholders. [21] All of the Brick-and-Mortar Retailers and two of the E-Commerce Retailers require directors to receive a majority of the votes cast to be elected in an uncontested election. Three out of five E-Commerce Retailers, however, only require that directors receive a plurality of votes (i.e., receive more votes than a competing candidate) in order to be elected to the board. These three E-Commerce Retailers all went public in the last seven years. In contrast, the two E-Commerce Retailers with a majority voting standard, Amazon and eBay, have been public for over two decades.

E. Say-On-Pay Approval

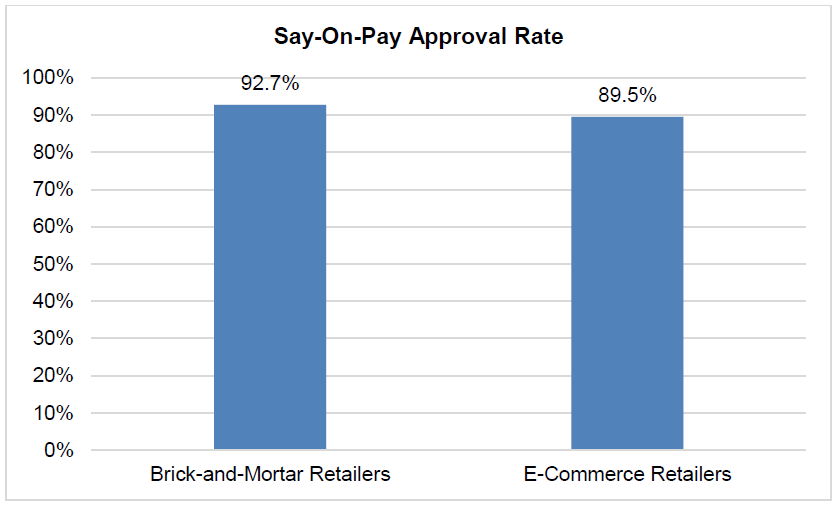

Section 14A of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 requires all public companies to hold a “say-on-pay vote,” which is an advisory vote of the shareholders to approve executive officer compensation. The average “say-on-pay” approval rate for the Retail Companies at their most recent shareholder meetings was 91.6%, or just above the average approval rate of 91% for Russell 3000 companies in 2020. [22] Only four Retail Companies received approval rates of less than 90%, with the lowest approval rate at 70.3%. This aligns generally with trends in say-on-pay approval rates for public companies overall, with approximately 93% in 2021 having say-on-pay approval rates of at least 70%. [23] E-Commerce Retailers had a slightly lower approval rate, with an average of 89.5% as compared to the average approval rate of 92.7% amongst Brick-and-Mortar Retailers.

F. Shareholder Proposals

Brick-and-Mortar Retailers are more likely than E-Commerce Retailers to have shareholder proposals included in their proxy statement for voter consideration at their annual meetings. In their most recent proxy statements, 78% of Brick-and-Mortar Retailers noted at least one potential shareholder proposal for voter consideration compared to only 40% of E-Commerce Retailers.

V. Trends in Corporate Disclosures

A. Corporate Responsibility Reports

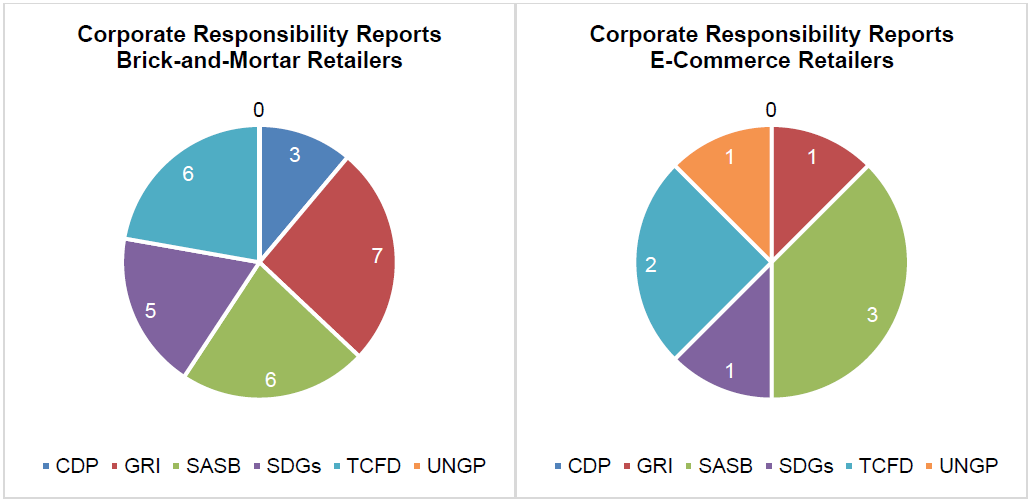

Many companies have enhanced their disclosures related to their environmental, social, and governance (“ESG”) practices. Companies frequently publish ESG information in corporate social responsibility (“CSR”) reports. Companies also commonly benchmark their ESG data, particularly sustainability data, using one or more third-party reporting frameworks, including the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (“TCFD”), the Global Reporting Initiative (“GRI”), and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (“SASB”) frameworks. [24]

Eleven of the Retail Companies sampled published CSR reports in 2020, with Brick-and-Mortar Retailers being more likely to publish ESG disclosures than the E-Commerce Retailers sampled. Amongst Brick-and-Mortar Retailers, GRI, SASB, and TCFD were the most popular frameworks used. This aligns generally with the most popular frameworks used by E-Commerce Retailers, though E-Commerce Retailers were more likely to favor SASB metrics than Brick-and-Mortar Retailers. Most Retail Companies tended to follow their chosen frameworks strictly, though Walmart and Dollar Tree only provided selected disclosures “guided by” these frameworks.

Conclusion

The Retail Companies are increasingly well-aligned with the recent governance trends and profiles seen at companies across the S&P 500. While the E-Commerce Retailers may in some instances offer more limited shareholder rights, both the Brick-and-Mortar Retailers and E-Commerce Retailers are generally in-line with, and in some instances, ahead of, the S&P 500 with respect to diversity, committee structures, and board expertise. Analyzing broader industry trends can be helpful, though retail companies should continue to determine their governance practices based on their particularized needs and objectives.

Annex A: Retail Companies Reviewed

| Brick-and-Mortar Retailers | E-Commerce Retailers |

|---|---|

|

|

Endnotes

1To evaluate current governance trends in the retail industry, we reviewed the recent proxy statements, annual reports, and website disclosures of a representative sample of retail companies with a market capitalization above $24 billion. Of these companies, nine are traditional retail companies whose business model is based around brick-and-mortar stores, and five are e-commerce companies that operate few, if any, physical stores. A list of the specific companies reviewed is provided in Annex A to this post. Thank you to Molly Mueller and Angela Wu for their research contributions to this publication.(go back)

2Chewy’s relatively recent IPO in 2019 may impact some of the data. For selected impacted data points for the E-Commerce Retailers, we show the data with and without Chewy.(go back)

3Spencer Stuart, 2020 U.S. Spencer Stuart Board Index (2020), https://www.spencerstuart.com/media/2020/december/ssbi2020/2020_us_spencer_stuart_board_ index.pdf.(go back)

4The average number of new directors added per year was calculated using the number of new directors added in the last five years for each company except the recently IPO’d E-Commerce Retailers (Wayfair, Chewy, and Etsy), where we used the number of new directors added since each company’s IPO.(go back)

5Spencer Stuart, supra note 3.(go back)

6Id.(go back)

7Nasdaq, Continued Listing Guide March 2021 (2021) https://listingcenter.nasdaq.com/assets/continuedguide.pdf; NYSE, Listed Company Manual (2021), https://nyseguide.srorules.com/listed-company-manual.(go back)

8Where a company did not explicitly disclose the demographic characteristics of directors in relation to gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, etc. in its official publications, we did not make assumptions or inferences on the basis of individual director photos, biographies or other publicly available information.(go back)

9Spencer Stuart, supra note 3.(go back)

10Every company used “Mr.” or “Ms.” prefixes, which formed the basis for our identification of female committee chairs.(go back)

11Spencer Stuart, supra note 3.(go back)

12NASDAQ, NASDAQ’s Board Diversity Rule (Aug. 17, 2021), https://listingcenter.nasdaq.com/assets/Board%20Diversity%20Disclosure%20Five%20Things.pdf.(go back)

13EEO-1 Data Collection, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (July 12, 2021), https://www.eeoc.gov/employers/eeo-1-data-collection.(go back)

14Sullivan & Cromwell LLP, 2021 Proxy Season Review: Part 1—Rule 14a-8 Shareholder Proposals (July 27, 2021), https://www.sullcrom.com/files/upload/sc-publication-2021-Proxy-Season-Review-Part-1-Rule14a-8.pdf.(go back)

15Id.(go back)

16Diversity Strategy, Goals & Disclosure: Our Expectations for Public Companies, State Street Global Advisors (Aug. 27, 2020), https://www.ssga.com/us/en/intermediary/etfs/insights/diversity-strategy-goals-disclosure-our-expectations-for-public-companies.(go back)

17NY State Comptroller DiNapoli Calls on Corporate America to Address Lack of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion, Office of the New York State Comptroller (Feb. 25, 2021), https://www.osc.state.ny.us/press/releases/2021/02/ny-state-comptroller-dinapoli-calls-corporate-america-address-lack-diversity-equity-inclusion.(go back)

18Takeover Defense Comparison Statistics, Deal Point Data(Sep. 23, 2021), https://www.dealpointdata.com/rj?vb=Action.intras&app=corp&id=q-1290847373.(go back)

19Id.(go back)

20Edward B. Rock, Does Majority Voting Improve Board Accountability, Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance (Nov. 27, 2015) https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2015/11/27/does-majority-voting-improve-board-accountability/.(go back)

21Id.(go back)

22Todd Sirras et al., 2020 Say on Pay & Proxy Results, Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance (Mar. 13, 2021), https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2021/03/13/2020-say-on-pay-proxy-results/.(go back)

23Sullivan & Cromwell LLP, 2021 Proxy Season Review: Part 2—Say-On-Pay Votes and Equity Compensation (Aug. 23, 2021), https://www.sullcrom.com/sc-publication-2021-Proxy-Season-Review-Part-2-Say-on-Pay-Votes-Equity-Compensation.(go back)

24Other frameworks used include the Carbon Disclosure Project (“CDP”), United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (“SDGs”), and the United Nations Global Compact (“UNGC”).(go back)

Print

Print