Matteo Tonello is Managing Director of ESG Research at The Conference Board, Inc. and Paul Hodgson is Senior Advisor to ESGAUGE. This post relates to Corporate Board Practices in the Russell 3000, S&P 500, and S&P MidCap 400: 2021 Edition, an annual benchmarking study and online dashboard published by The Conference Board and ESG data analytics firm ESGAUGE, in collaboration with Debevoise & Plimpton, the KPMG Board Leadership Center, Russell Reynolds Associates, and The John L. Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware.

Corporate Board Practices in the Russell 3000, S&P 500, and S&P MidCap 400: 2021 Edition documents corporate governance trends and developments at US publicly traded companies—including information on board composition and diversity, the profile and skill sets of directors, and policies on their election, removal, and retirement. The analysis is based on recently filed proxy statements and complemented by the review of organizational documents (including articles of incorporation, bylaws, corporate governance principles, board committee charters, and other corporate policies made available in the Investor Relations section of companies’ websites).

The project is conducted by The Conference Board and ESG data analytics firm ESGAUGE, in collaboration with Debevoise & Plimpton, the KPMG Board Leadership Center, Russell Reynolds Associates, and the John L. Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware.

The following are the key findings and insights.

For the first time in our annual analysis of proxy statements, in 2021 the majority of S&P 500 companies have disclosed the racial (ethnic) makeup of their boards. According to the disclosure available, boards remain overwhelmingly white, with some business sectors disclosing far more racial diversity than others. This is also true for newly elected directors for which demographic information is made public—less than one-fourth of them are non-white. Companies should consider committing to a multi-year board succession plan where the search for strategic skills and expertise is accompanied by a sustained focus on diversity. They should also investigate best practices on the integration of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) metrics into senior executives’ incentive plans, and continue to improve disclosure of board racial and ethnic diversity.

Corporate disclosure of the racial (ethnic) diversity of board of directors has grown exponentially in the last couple of years. According to proxy statements filed as of June 30, 2021, for the first time a majority of S&P 500 companies (59 percent) included this type of information, which is based on self-disclosure by individual directors; the figure was 24 percent last year, 15 percent in 2019, and a mere 3.1 percent in 2016. Unlike other governance disclosure practices, which typically take years to extend to market segments beyond the large group of companies that compose the S&P 500 index, the practice of providing more granular disclosure on the diversity makeup of corporate boards is rapidly expanding to the S&P MidCap 400 and the Russell 3000. In the 2021 proxy season, 32.6 percent of S&P MidCap 400 companies and 26.9 percent of the Russell 3000 companies included information on the racial (ethnic) composition of their board.

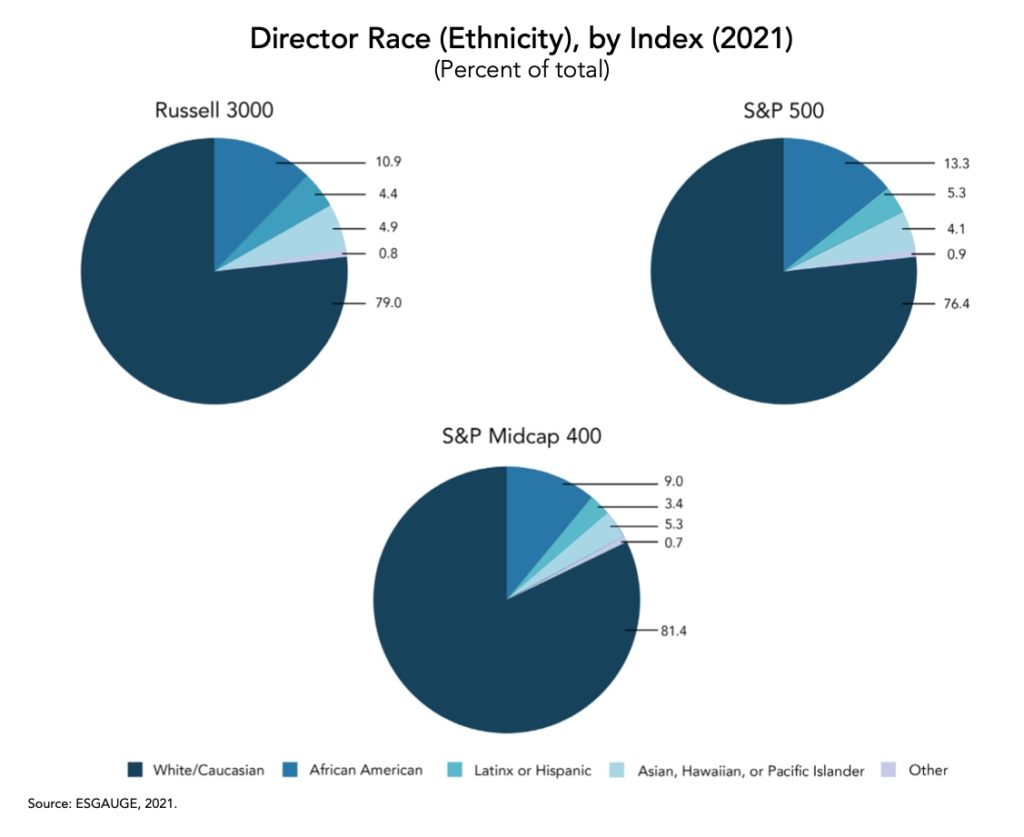

Among S&P 500 companies that disclose their directors’ race (ethnicity), 76.4 percent self-identify as white, 13.3 percent as African American, 5.3 percent as Latinx or Hispanic, and 4.1 percent as Asian, Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander. The remaining 0.9 percent report a different ethnic background from those listed above. There are slightly more Asian, Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander directors among S&P MidCap 400 companies (5.3 percent) and in the Russell 3000 (4.9 percent). However, in the S&P MidCap 400, the percentage of African American directors sitting on boards providing this type of disclosure is lower than the level of the S&P 500, or 9 percent. In the Russell 3000, it is 10.9 percent.

The Russell 3000 index breakdown reveals stark differences in disclosure practices by business sectors. For example, the companies that are more likely to disclose the racial (ethnic) background of their board members are in the utilities and consumer staples sectors (50 percent and 43.8 percent, respectively). In contrast, only 16.7 percent of health care companies and 19.8 percent of communications services firms provide this type of public disclosure.

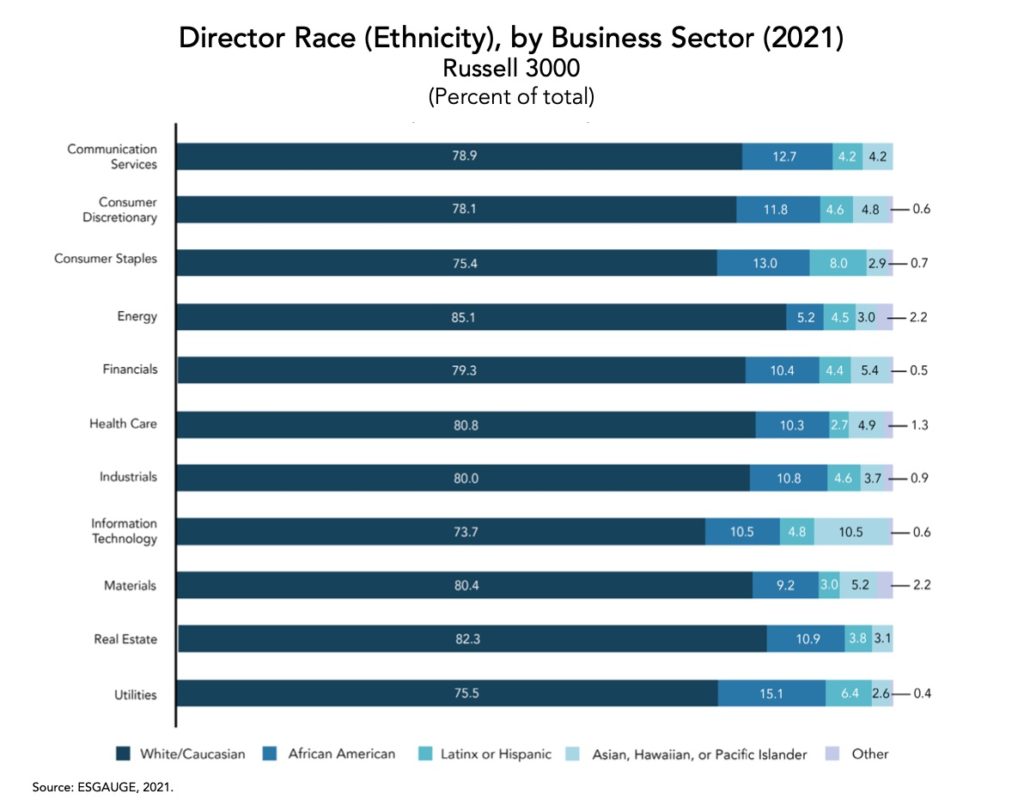

Among the Russell 3000 companies that provide such disclosure, the highest percentage of directors who self-identify as African American is found in the utilities sector (15.1 percent), followed by the consumer staples and the communications services sectors (13 percent and 12.7 percent, respectively). The lowest percentages are in the energy and materials sectors (5.2 percent and 9.2 percent, respectively). Only 2.7 percent of the Russell 3000 companies in the health care sector that disclose information on their directors’ race (ethnicity) report board members who self-identify as Latinx or Hispanic. Of directors at consumer staples companies including such disclosure, 8 percent self-identify as Latinx or Hispanic. Of all sectors, information technology companies report the highest percentage of Asian, Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander (10.5 percent) while utilities companies report the lowest (2.6 percent).

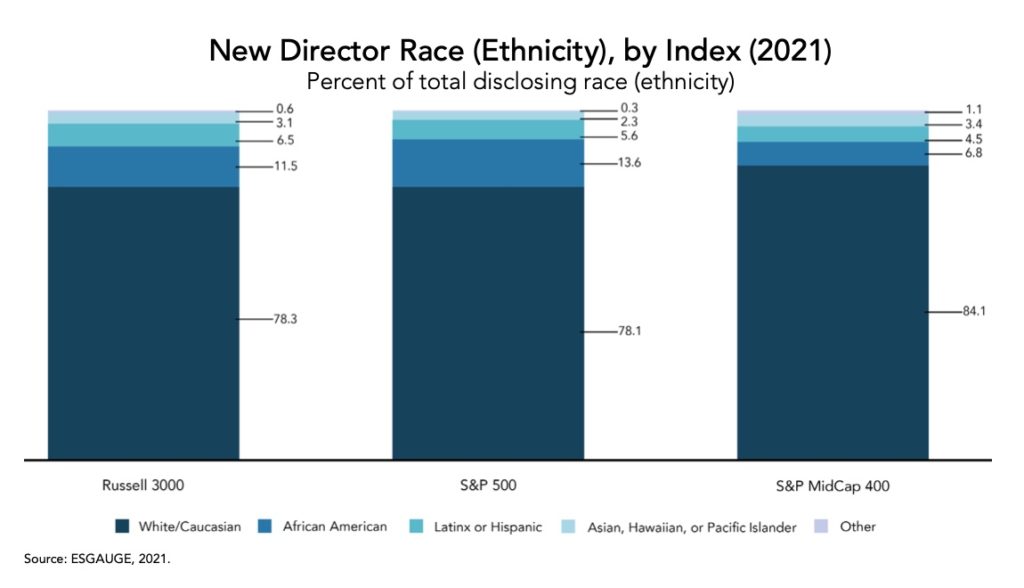

The diversity analysis was complemented with a review of the population of newly elected directors in 2021. In all examined indexes, of all new directors at companies that publicly shared the self-disclosure of racial (ethnic) backgrounds, more than three quarters continue to be white or Caucasian. The S&P 500 had the highest percentage of newly elected African American directors so far this year, or 13.6 percent, compared to 11.5 percent of the Russell 3000 and only 6.8 percent of the S&P MidCap 400.

What’s ahead? Ensuring the racial (ethnic) diversity of board members will be an imperative for US public companies in the next few years, as pressure from multiple stakeholders will only rise from here. In the last year alone, we have witnessed a social reckoning on a scale that was not seen before. The racial justice movement has galvanized consumers and employees. [1] It has also become a catalyst for bold actions from legislatures and large institutional investors, ultimately urging corporate leaders to move DEI issues to the front and center of their corporate policy agendas. [2] To mark the adoption of a new, unambivalent stance on this matter, in July 2020, a coalition of trade organizations including the US Chamber of Commerce and the American Bankers Association sent a letter to the US Senate Banking Committee in support of a bill already adopted by the US House of Representatives that would mandate proxy disclosure of self-identified race, ethnicity, and gender of corporate board members and executive officers. [3] (Following the inauguration of the new US Congress in January 2021, that bill was reformulated into a new legislative proposal titled “Improving Corporate Governance Through Diversity Act of 2021”). [4]

Board members and senior executives should help their companies navigate these business and social changes. They should appreciate the historical importance of this moment and embrace the values that underpin it. To do so, they should lead by example and address diversity imbalances in board composition and senior management. Those companies that do not yet have any diverse board members should make a clear, public commitment to change. The following should become key priorities, especially for boards that have not yet given a clear public indication of their commitment in this area:

- Revisit director performance assessment processes to ensure they promote skill renewal and the injection of new ideas and perspectives. Directors should appreciate the importance of maintaining diversity of tenures across the board and commit to a healthy rate of refreshment.

- Develop a multi-year board succession plan where the need for strategic skills and expertise is evaluated through the lens of diversity and inclusion. The long-term plan should include developing relationships with diverse junior executives who may one day become attractive director candidates for boards of other companies. Rather than an episodic exercise, director succession should align with an ongoing board development program and be rigorously informed by an emphasis on diversity.

- Investigate best practices on the integration of DEI metrics into senior executives’ incentive plans. Recent studies illustrate how more and more companies, including large ones, have started to set executive targets meant to raise minority representation in managerial positions. [5] Many companies that are still lagging in the promotion of diversity, equity, and inclusion have much to learn from peer experiences. Moreover, setting DEI objectives can help to develop a diverse pool of senior managers who could one day aspire to become board nominees. To support these endeavors, in July 2021, The Conference Board has introduced a new screening tool to its ESG Advantage Benchmarking Platform that allows access to granular information on the use of ESG-related metrics of performance across the Russell 3000 index. [6]

- Consider adopting a Board Diversity Matrix disclosure model that complies with the guidelines recently published by the NASDAQ Listing Center. The information provided (whether in the proxy statement or the company’s corporate website) must be based on the self-identification of each member of the board of directors. For a US incorporated company, any director who chooses not to disclose a gender should be included under “Did Not Disclose Gender” and any director who chooses not to identify as any race or not to identify as LGBTQ+ should be included in the “Did Not Disclose Demographic Background” category. Following the first year of adoption of the Matrix, to allow readers to appreciate the progress made, the guidelines establish that all companies must include in their disclosure the current year and immediately prior year diversity statistics. [7]

- Some commentators have observed that the new California law, other similar new state laws, and the NASDAQ listing rule have missed the opportunity to extend the notion of board diversity to executives with disabilities. In a press release following the approval of the NASDAQ rule, in particular, Disability:IN (a global organization driving disability inclusion and equality in business) and the American Association of People with Disabilities (AAPD) expressed their deep disappointment with the SEC’s decision, which took place despite the vigorous lobbying campaigns by a wide group of stakeholders—including New York State Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli, the Leadership Council on Civil and Human Rights, the National LGBT Chamber of Commerce, the US Black Chamber and Women Impacting Public Policy. [8] Boards of directors committed to a more diverse and inclusive leadership development and board recruitment program can remedy this omission. They can learn from experiences such as the Valuable 500, a global disability network launched at the annual Davos gathering of business leaders hosted by the World Economic Forum in 2019: the organization recently announced having reached its target of 500 major companies that officially put disability inclusion on their boardroom agenda—including Microsoft, Unilever, Google, and Coca-Cola. [9]

The corporate boardroom, which has long been a predominantly male preserve, continues to make progress on gender diversity. Both in small and mid-size companies, the number of female directors is showing marked increases and, among new directors, more than one-third are women. By now, the largest companies have more boards with three, four or more than four females than boards with one or two. Those smaller entities that do not yet have any female board members should make a clear, public commitment to change. While a sound succession planning process is the most effective way to promote refreshment and the election of diverse candidates, boards may also wish to consider other practices. These include endorsing the model proposed by the Committee for Economic Development of The Conference Board (CED), where every other board seat vacated by a retiring board member is filled by a woman. In addition, directors could temporarily increase the size of the board, introduce (and adhere to) overboarding restrictions, and adopt guidelines on expected board tenure.

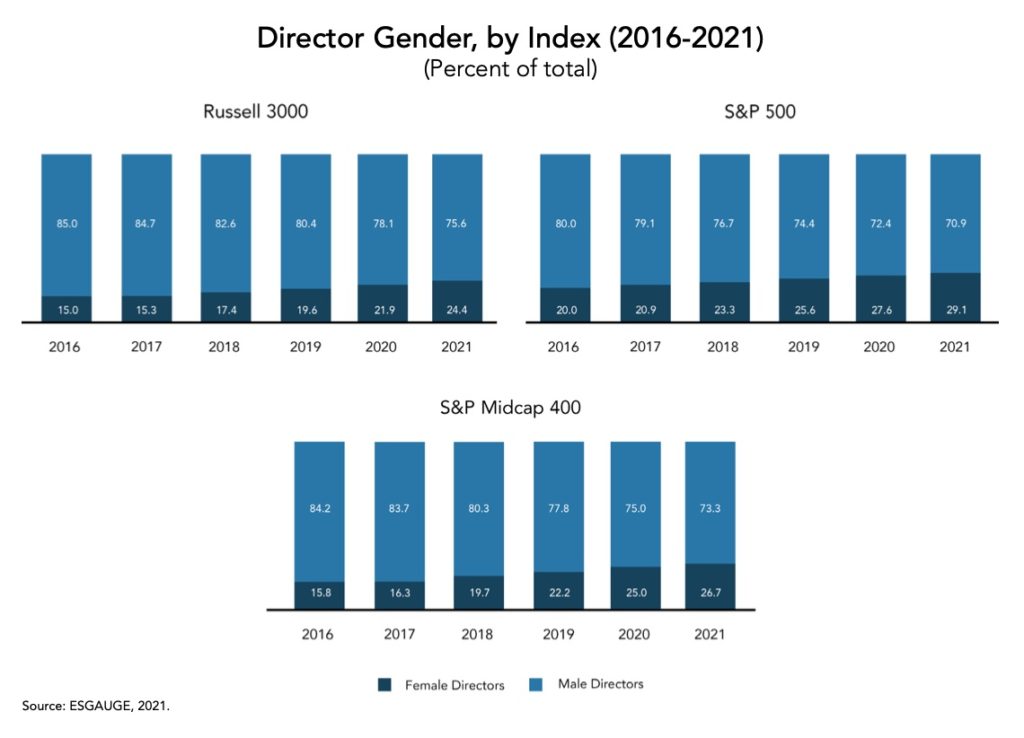

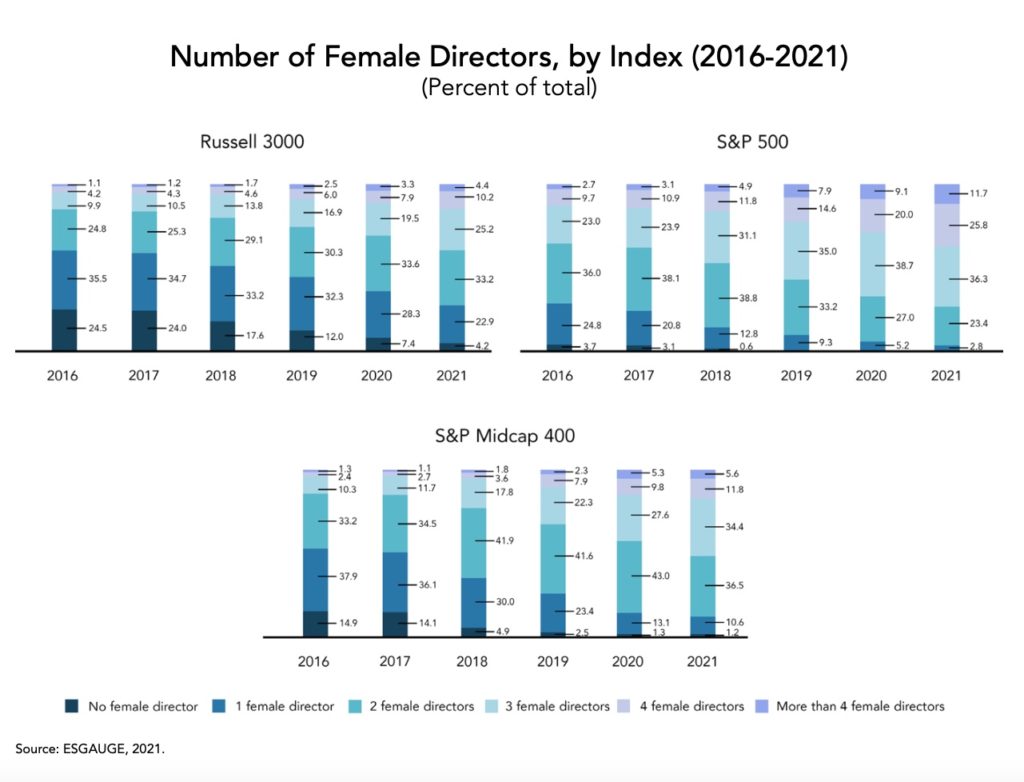

The average percentage of women serving on the board of directors continues to rise in both the S&P 500 (from 20 in 2016 to 29.1 in 2021) and the Russell 3000 index (from 15 to 24.4), but the largest increase is reported by S&P MidCap 400 companies—from 15.8 percent in 2016 to 26.7 percent in 2021.

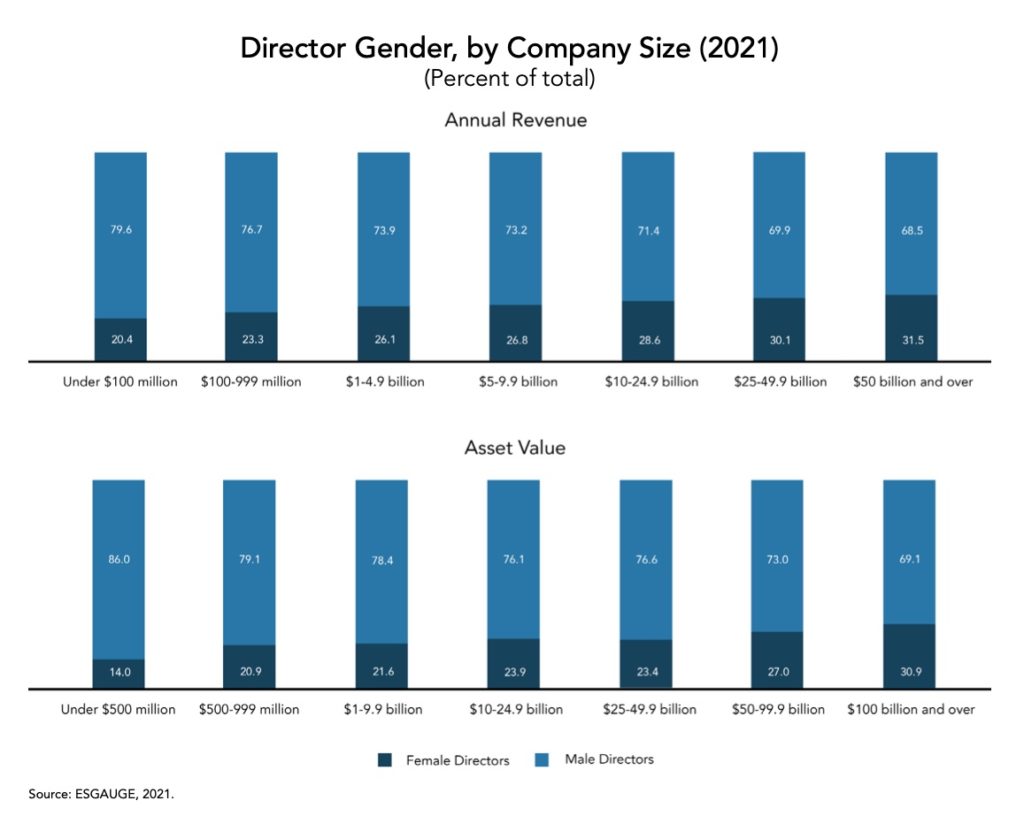

Generally, there is a direct correlation between company size and gender diversity in the boardroom, with the highest percentage of female directors concentrated among boards of larger companies. For example, according to 2021 proxy disclosure, 31.5 percent of directors at manufacturing and nonfinancial services companies in the Russell 3000 with annual revenue of $50 billion or more are women, compared to only 20.4 percent of those in smaller companies with annual revenue of $100 million or less. In the financial and real estate sectors, the 30.9 percent of female directors disclosed by companies with asset value of $100 billion or more compares to the 14 percent found at companies valued under $500 million.

In the Russell 3000 index, 4.2 percent of companies still have no female representative on their board of directors. The number has dropped significantly from 2016 levels, when it was 24.5 percent; it is also just one-third of what was recorded in 2019 alone (12 percent). By comparison, in the S&P MidCap 400 only just over 1 percent of companies have no female directors and the S&P 500 celebrated in 2019 the disappearance of the all-male board. An equally remarkable finding is that, while the percentage of companies with only one or two female directors is lower than it was in 2016, in the same time period the percentage of companies with three, four and more than four female directors has been growing exponentially. This trend can be generally observed across indexes but is quite pronounced in the S&P 500 index. For example, about one-fourth of companies had only one female director in 2016, and the percentage has dropped to a mere 2.8 percent in 2021; on the other hand, in 2016, 23 percent of the S&P 500 companies had three female directors and 9.7 percent had four, and those shares have grown to 36.3 percent and 25.8 percent, respectively, in 2021. Today, more than 11.7 percent of S&P 500 companies have more than four female board members, or more than four times as many as those reported in 2016.

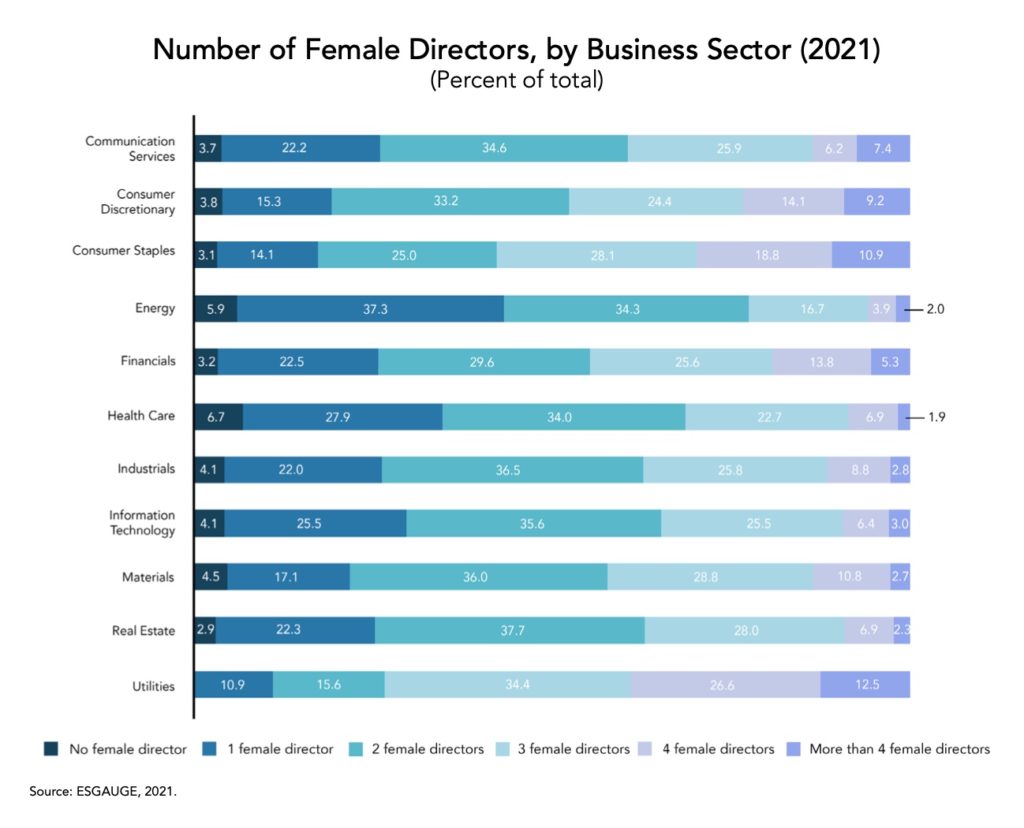

The utilities sector has the highest percentage of Russell 3000 companies with more than four female directors (12.5 percent), while the health care sector has the lowest (1.9 percent). Health care companies disclosed the highest percentage of boards with no female representation (6.7 percent), while none of the utilities companies in the Russell 3000 index reported still having all-male boards. The energy sector reported the highest percentage of companies with just one female directors (37.3 percent) and the lowest with three female directors (16.7 percent—it is 34.4 percent among utilities firms).

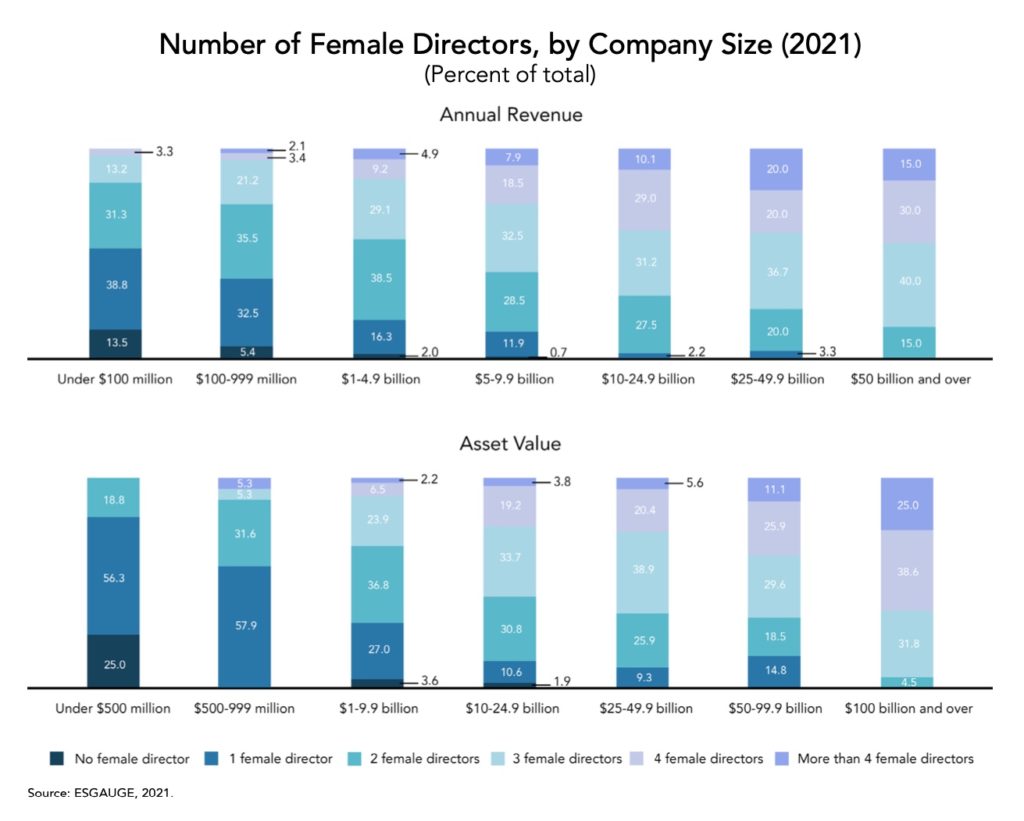

The company size analysis is also quite insightful as it shows that larger organizations have been the most responsive to the demand for gender diversity in the boardroom. First, none of the largest manufacturing and nonfinancial services companies (with revenue of $25 billion or higher) and none of the largest financial services and real estate companies (with asset value of $100 billion and over) have all-male boards of directors. On the contrary, in the smallest manufacturing and nonfinancial services companies, with annual revenue under $100 million, 13.5 percent continue to have no female directors, and the share is even higher in financial services and real estate firms with asset values under $500 million, at 25 percent. Second, the analysis clearly shows that the largest companies have gone well beyond the election of one or two female directors. For example, of financial services and real estate firms with asset value of $100 billion and over, 31.8 percent have three female board members, 38.6 percent have four, and as much as 25 percent have more than four. In that subgroup of companies, only 4.5 percent have only two female directors and there are no companies with only one woman serving on the board.

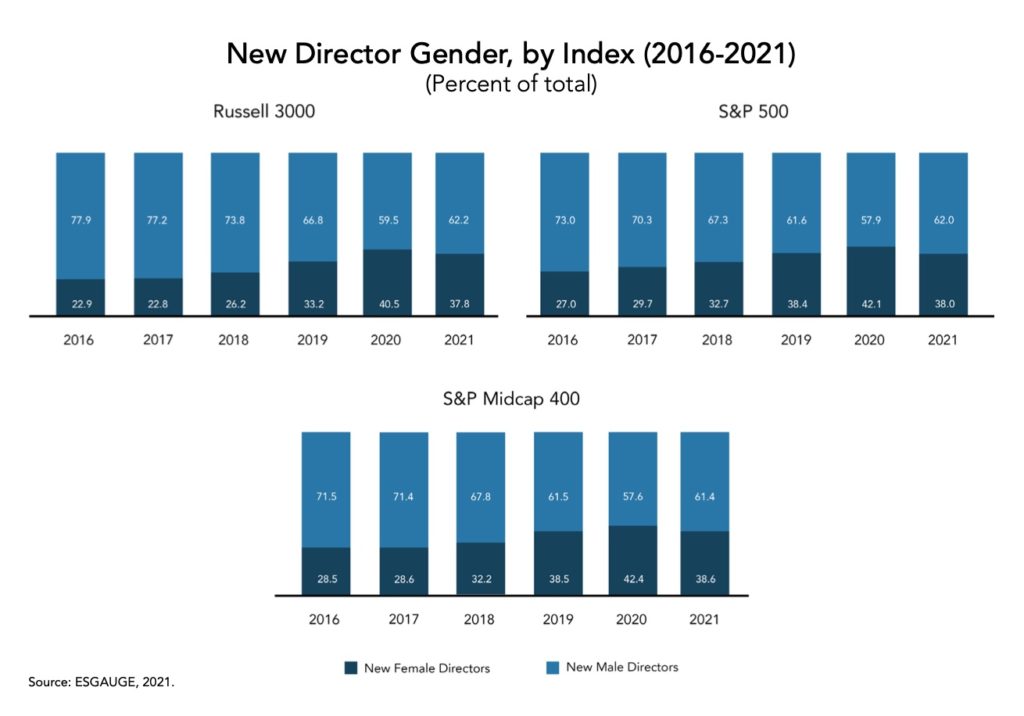

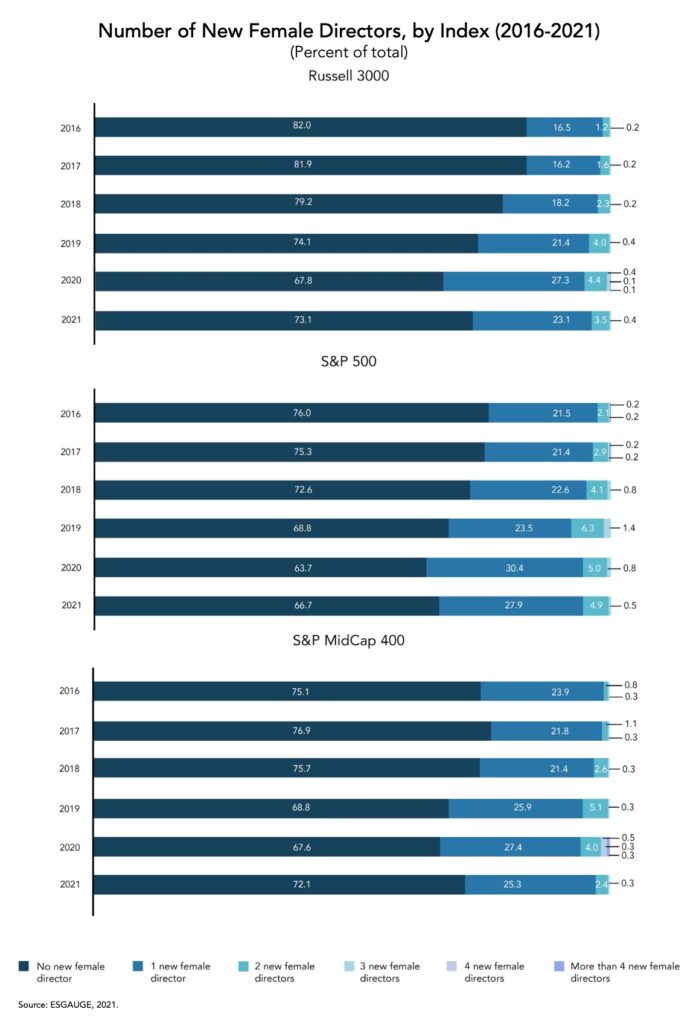

The analysis zeroed in on the population of newly elected directors in 2021 and found that, despite the progress on diversity, most new directors continue to be male. In the S&P MidCap 400, for example, 38.6 percent of newly elected directors in 2021 were female, compared to 61.4 percent who were male. Statistics for the S&P 500 and Russell 3000 indexes are quite similar. While these findings show that corporations are changing the gender balance of their boards, what is most striking is the increase in the proportion of new female directors compared to 2016. For example, in the Russell 3000, the proportion of new directors who were women has almost doubled, from 22.1 percent to 37.8 percent. Nonetheless, about three-quarters of companies in the Russell 3000 and the S&P MidCap 400 as well as 66.7 percent of companies in the S&P 500 elected no new female directors in 2021, while almost all of the remaining companies elected just one.

Why does it matter? Drawing on research that links diversity and firm performance, investors demand that boards become more gender diverse and promote diversity in their organizations. [10] State Street Global Advisors was among the first large asset managers to be vocal on gender diversity, launching its Fearless Girl campaign on the eve of International Women’s Day in 2017. [11] And in the last few years alone the request to elect diverse directors has rapidly been embraced by other high-profile shareholders. BlackRock, for example, now encourages companies to have at least two women on their boards. Although their approach is to first engage portfolio companies on the need to improve their board diversity of genders, BlackRock may vote against directors (for example, those serving on the nominating committee) if insufficient progress is made. [12]

Legislative and self-regulatory initiatives aimed at advancing board diversity also continued to intensify in the last year. In August 2021, the SEC approved NASDAQ’s new listing standards on board diversity. [13] In addition to requiring “transparent diversity statistics regarding their board of directors”, the provisions expect most NASDAQ-listed companies “to have, or explain why they do not have, at least two diverse directors, including one who self-identifies as female and one who self-identifies as either an underrepresented minority or LGBTQ+.” Yet, only a few days after its approval by the SEC, the new listing provision was challenged in court. [14]

The NASDAQ listing standard was not alone in coming under challenge. California’s board diversity legislation, [15] which became the model for several other bills at the state legislature level, was also met with opposition. In particular, a shareholder of a publicly traded company filed suit [16] against the Secretary of State of California, alleging that the diversity statute was unconstitutional under the equal protection provisions of the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution. While the litigation was initially dismissed, in June 2021 a higher court reversed this decision and allowed the case to go forward. [17]

Despite these forms of resistance to change, the all-male board is fast becoming obsolete and the vast majority of corporate boards recognize the value of gender diversity. Diversity is not a check-the-box compliance exercise and companies should not relent in the pursuit of some form of gender balance on their board. Those smaller entities that do not yet have any female board members must make a clear, public commitment to change. While a sound board succession planning process is the most effective way to promote refreshment and the election of diverse candidates, boards may also consider other practices, including endorsing the model proposed by the Committee for Economic Development of The Conference Board (CED), where every other board seat vacated by a retiring board member is filled by a woman. [18] In addition, directors could temporarily increase the size of the board, introduce (and adhere to) overboarding restrictions, and adopt guidelines on expected board tenure.

The scope of directors’ oversight responsibilities has been expanding in the last decade, including in the ESG area. But an analysis of board committee structures shows that companies still opt for the delegation of new duties to existing committees rather than the creation of new standing committees. Some exceptions may be found in certain sectors—notably, the energy, materials, and utilities sectors, where more boards are forming specialized environment, health & safety committees. Smaller companies, which tend to have smaller boards and committees, may find it more practical to keep the oversight of new ESG issues at the full board level and frequently add those issues to the board meeting agenda—just as a board committee would do for any of its own core responsibilities.

The Conference Board and ESGAUGE have conducted a historical analysis of existing board committees across the Russell 3000, the S&P 500, and the S&P MidCap 400. The review indicates that most US public companies have not (yet) responded to the steady expansion of director responsibilities observed through the last decade by substantially reorganizing their governance structure. This finding corroborates the anecdotal evidence that, when new duties are added to board committee charters, they tend to be delegated to existing committees or retained at the full-board level. [19]

In all examined indexes and company size groups, the only committee types that show a slow rise in numbers are the risk committee, the science & technology committee, and the environment, health & safety committee. And yet those committees continue to be found only in a small minority of boards of directors. For example, despite the growing concerns about issues of climate change risk oversight and the pressure to expand disclosure on the matter, the review of board committee names as of December 31, 2020 shows that only 3.2 percent of Russell 3000 companies have instituted an environment, health & safety committee, up from the 2.8 percent registered in 2016. (The percentages are only slightly higher in the S&P MidCap 400 and the S&P 500, at 4.3 and 8.5 percent).

Some exceptions may be emerging in specific business sectors, a finding that could reflect the heightened scrutiny of certain ESG-related matters to which those industries are subject. For example, the energy sector has the largest share of Russell 3000 companies with environment, health & safety committees of the board of directors (or 23.9 percent), though materials and utilities companies are close behind (22.2 and 19.4 percent, respectively). About one out of five real estate companies have instituted an investment/pension committee (17.6 percent, followed by financials at 8.6 percent). Across business sectors, highly regulated utilities companies have the most committee types, including the highest percentage of public policy committees (9.7 percent, up from 2.9 percent in 2016).

Aside from the traditional audit, compensation, and nominating/governance committees, the most common standing committees of the board of directors are the executive committee and the finance committee. They are seen more often among larger and more complex organizations: For example, executive committees are found in 38 percent of boards of directors of Russell 3000 companies with annual revenue of $50 billion or higher (the largest size group in our size breakdown), and their presence becomes more and more sporadic across smaller company size groups—down to only 2.2 percent of boards of companies with annual revenue under $100 million (the smallest size group in our size breakdown). Similarly, 36 percent of boards in the largest size group have a finance committee, compared to only 2.8 percent of those in the smallest size group.

What’s ahead? As with most other governance matters, there is no single answer to the question of what committees the board of directors should institute to perform its duties. This is particularly true now that issues of ESG risk oversight are increasingly being elevated to the attention of the board. The ESG Center at The Conference Board, in collaboration with ESGAUGE, has started to examine how committee charters are being amended to reflect the responsibility for ESG oversight. The data collection will inform a new tool in the ESG Advantage Platform that maps the delegation of new duties to board committees and the formation of new standing committees.

In general, while some tasks related to ESG oversight should be kept at the full-board level (or assigned to a dedicated ESG committee), the breadth and interdisciplinary nature of ESG warrants the delegation of specific responsibilities to the audit, compensation, and nominating/governance committees:

- The full board is better suited to address top-level issues such as the alignment between ESG and the business strategy, which is critical to allocate resources to ESG risk mitigation and to ESG opportunities. Also, the full board should consider overseeing and holding management accountable for setting the direction the company should follow with respect to ESG disclosure, given that for the most part this type of disclosure continues to be voluntary.

- Data collection processes and the controls needed to ensure that information on ESG gathered across the company is investor grade are generally tasks for the audit committee, given the experience audit committee members already have with financial disclosure controls and procedures. Similarly, the audit committee is the best suited to make decisions on ESG disclosure assurance, when an independent assurer is involved.

- As discussed above, more and more companies are exploring how to set executive incentives to drive ESG and other types of extra-financial performance. The compensation committees can perform a critical role in aligning executive compensation to ESG objectives and integrating ESG into considerations of incentive design.

- The increasing importance of ESG matters raises the question of whether the company board and senior leadership have the skill set and experience necessary to oversee and carry out an ESG-informed strategy. [20] This issue is becoming relevant to board recruitment, and it can be logical for the nominating/corporate governance committee to be tasked with it. As with the desire to recruit directors from more diverse backgrounds, board nominating committees need to focus on a more diverse skill set for directors in order to meet future challenges such as climate change, DEI, cyber security, and technological advances such as artificial intelligence. They should also evaluate the need for internal skill sets against the opportunity to access specialized knowledge by retaining outside advisors.

- The Conference Board recently found that, for the first time in many years, the role of total shareholder return (TSR) as a driver of CEO succession decisions might be starting to diminish, in a sign of the growing importance of ESG and extra-financial performance. [21] Nominating/corporate governance committees, which are typically responsible for CEO succession planning and leadership development, can ensure that leadership development programs give enough attention to developing ESG-related skills.

- Smaller companies, which tend to have smaller boards and committees, may find it more practical to keep the oversight of new ESG issues at the full board level and frequently add those issues to the board meeting agenda—just as a board committee would do for any of its own core responsibilities.

The trend toward CEO-board chair separation, previously more pronounced among smaller businesses in the Russell 3000, is extending to the S&P MidCap 400. Amid these governance changes, some companies are tapping leaders with different backgrounds, including in the military or the government. Regardless of the chosen leadership model, boards should safeguard their oversight authority and assure investors of their independence. In their periodic performance assessment, directors should conduct a candid review of the effectiveness of the leadership structure in place. Disclosure on the rationale for the chosen board leadership model should avoid generic, boilerplate language and discuss the specific circumstances that drove the decision at the company.

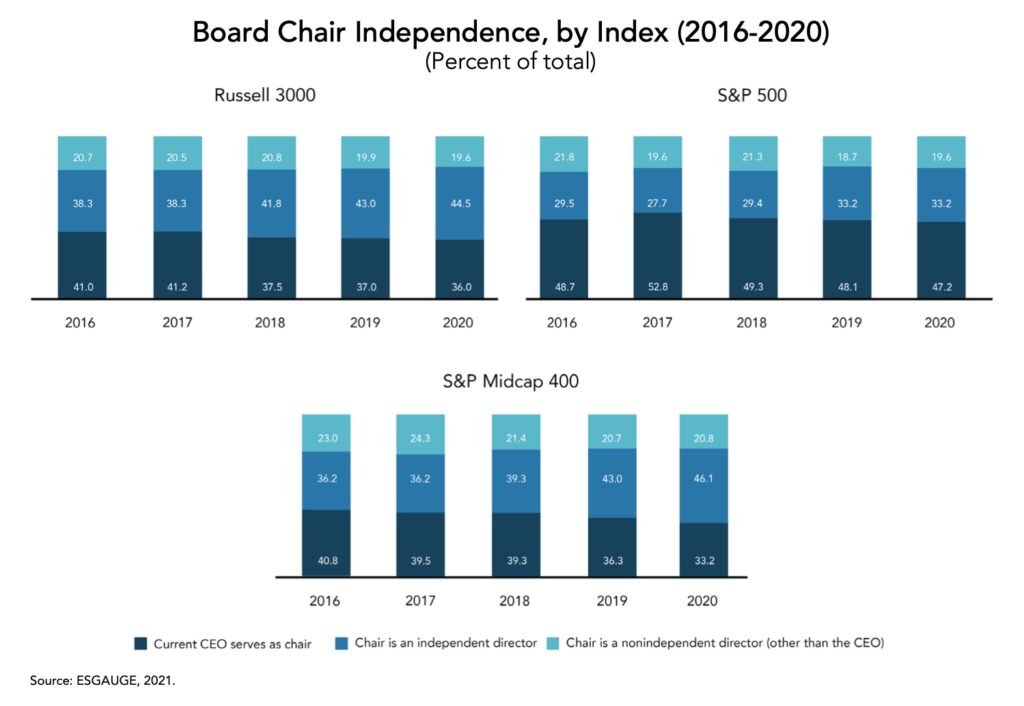

A review of board leadership structures across market indexes shows that more and more mid-sized companies are departing from the traditional model of CEO-chair combination. Only until recently, this trend was more common among the smallest companies in the Russell 3000. However, new data reveals that the rate of change to independent board leadership has been faster in the last couple of years in the S&P MidCap 400 than in the entire Russell 3000 index.

In 2016, the percentage of companies combining the roles of CEO and board chair was almost identical in both indexes: 41 percent in the Russell 3000 and 40.8 percent in the S&P MidCap 400. But the decline in prevalence of the combination model has since accelerated in the mid-market sector and, according to the most recent disclosure, only 33.2 percent of S&P MidCap 400 companies still combine the two roles, compared to 36 percent of Russell 3000 companies.

Our findings also show that, outside of the S&P 500 index, today’s most common approach to board leadership is to entrust the role of the chair to an independent member of the board of directors. Some 44.5 percent of Russell 3000 companies and 46.1 percent of S&P MidCap 400 companies have an independent board chair, whereas in 19.6 percent of Russell 3000 companies and 20.8 percent of S&P MidCap 400 companies the chair duties are performed by a non-independent director other than the CEO (e.g., the company founder).

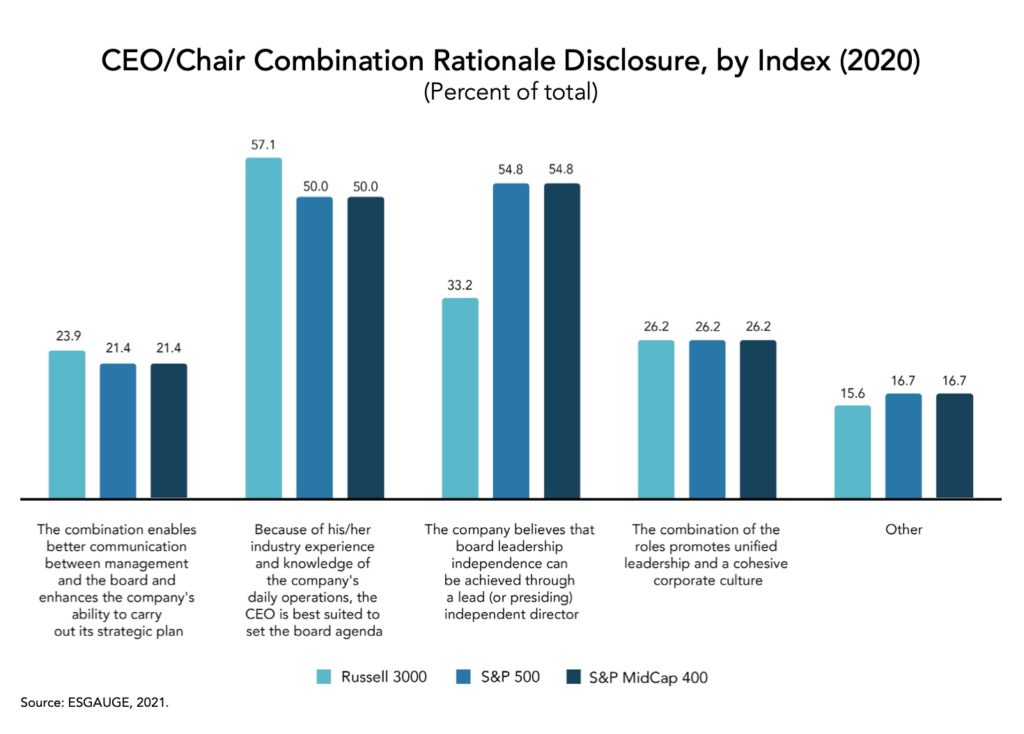

These board leadership practices contrast those found in the S&P 500 index, where only one third of companies (33.2 percent) have an independent board chair and almost half (47.2 percent, or a very small change from the 48.7 percent recorded in 2016) continue to combine the CEO and board chair roles. According to a review of corporate disclosure by these larger entities, the most commonly cited rationales for not separating the roles are the beliefs that board leadership independence can still be ensured through a lead (or presiding) independent director (an explanation found in 54.8 percent of S&P 500 cases) and that CEOs, because of their industry experience and knowledge of the company’s daily operations, are best suited to set the board agenda (50 percent). In fact, in almost all cases where the roles are combined, the company balances the authority of the CEO within the board by instituting a lead independent director. Most often, the lead director performs such duties as calling and chairing executive sessions (a responsibility described in 83.8 percent of the role descriptions included in S&P 500’s lead director charters) and acting as a liaison between non-executive directors and the CEO-chair (76.1 percent).

Our analysis extended to the professional background and to the qualifications and skills of board chairs. Even when independent, they have extensive strategy experience—gained either through their (current or former) service as CEOs (about 44.9 percent in the Russell 3000, 35.3 percent in the S&P MidCap 400, and 55.6 percent in the S&P 500) or through other (current or former) board leadership positions (20.8 percent in the Russell 3000, 26.1 percent in the S&P MidCap 400, and 17.1 percent in the S&P 500). There are also indications that some boards are increasingly seeking leadership skills developed outside of the top executive team or directorship roles. In particular, one fourth of manufacturing and nonfinancial companies with annual revenue under $4.9 million have a board chair that brings experience from below the C-Suite, while 22.2 percent of board chairs of manufacturing and nonfinancial companies with annual revenue between $25 million and $49.9 million spent their careers in government or the military. In the S&P MidCap 400, since 2016, the proportion of former CEOs serving as independent chairs fell from just under 40 percent to just over 30 percent, making room for other types of leadership backgrounds. Cases of board chairs with non-corporate backgrounds, for example in military or the government, are emerging in particular among utilities (13 percent), real estate (11.7 percent), and financial companies (7.8 percent), whereas they are absent or almost absent in other business sectors.

What’s ahead? In the United States, while endorsing the need for board independence, proxy advisors and the institutional investment community have generally rejected a strict one-size-fits-all approach to board leadership and entrusted the board to establish the best working relationship between the CEO, the chair, the lead independent director, and other directors.

Shareholder proposals requesting the separation of the CEO and board chair roles are common. In fact, according to the review of shareholder voting at annual general meetings conducted by The Conference Board and ESGAUGE, they were the second-most voted proposal type in the 2021 proxy season (with 44 voted proposals in the January 1-June 30 period), following resolutions to allow the company to act by written consent (87 proposals). However, these many filings most often come from individual investors (the main proponents this year were Kenneth Steiner and John Chevedden) and typically fail due to the lack of wide support from institutional shareholders and proxy advisors. [22] In its voting guidelines, ISS, in particular, identifies a few factors that will increase the likelihood of a recommendation in favor of these proposals—including evidence that the board has failed to oversee and address material risks facing the company or to adequately respond to material concerns raised by shareholders. The most recently approved proposals to appoint independent board chairs were put to a vote last year at Baxter International (NYSE: BAX) and The Boeing Company (NYSE: BA). [23] Following those votes, the companies amended their corporate governance principles to accommodate the new separation policies: Lawrence Kellner now serves as independent chair at Boeing, while at Baxter the new leadership model will be implemented upon the next CEO transition. [24]

Corporations should carefully weigh their own governance needs when choosing a board leadership model, as no single structure works for every business. When making this decision, the organization should consider existing board-management dynamics and regard director independence as its paramount interest. Some of the large companies that have traditionally used the combination model may hesitate to abandon it unless directors experience specific circumstances where the CEO infringed their independence or silenced them. On the other hand, research shows that director independence increases at CEO turnover and falls with CEO tenure, and those same organizations may conclude that the CEO succession event offers the right opportunity to transition the board leadership from the duality to the separation model. [25] In the last decade, in particular, the broadening scope of the board of directors’ risk oversight responsibilities has more clearly differentiated the role of board chair from the top executive function; by separating the two, a company can not only reinforce its public commitment to strong corporate governance but also draw on the leadership skills and business experience of two different individuals.

Whatever the choice of board leadership, companies should fully explain its rationale in their disclosure documents. This disclosure should avoid generic, boilerplate language and discuss the specific circumstances that drove the board leadership decision at the company. In particular, if the duality model is retained, the disclosure should detail the responsibilities that the lead independent director role will perform to counterbalance the concentration of powers in the combined CEO-chair functions.

Director election practices that are well established among larger US companies—including board declassification and majority voting—continue to elude much of the broader Russell 3000 index. But the demand for director diversity is not going to subside, and smaller businesses caught unprepared to execute a solid board succession plan may ultimately find themselves not only facing shareholder activism but also at a disadvantage in the competition for leadership talent.

There continues to be a significant divide between the S&P 500 and the Russell 3000 when it comes to governance practices that are critical to a sound board succession and refreshment process—including board declassification and the adoption of a majority voting system of director elections. Just as observed for board independence and the separation of CEO and board chair positions, the most interesting recent developments in this area can be ascribed to mid-size companies in the S&P MidCap 400.

A governance analyst reviewing organizational documents of S&P 500 companies would have the impression that a classified board, where directors do not face annual elections, is a thing of the past. [26] A closer look at the Russell 3000 does, however, belie that conclusion. While only one out of ten S&P 500 companies still have different classes of directors, each subject to staggered-year elections, the percentage rises to 40.8 in the Russell 3000—a mere 1.7 percentage point lower than in 2016. Classified boards, which make it more difficult for hostile or activist shareholders to gain control of the board, are also present in as much as 62.6 percent of small companies with annual revenue under $100 million and in 54 percent of those with revenue in the $100 million-999 million bracket. Most of the recent progress toward a declassified structure can be appreciated in the S&P MidCap 400, where the prevalence of staggered boards has declined by almost 10 percentage points in the last four years (or from 40.3 to 30.9 percent).

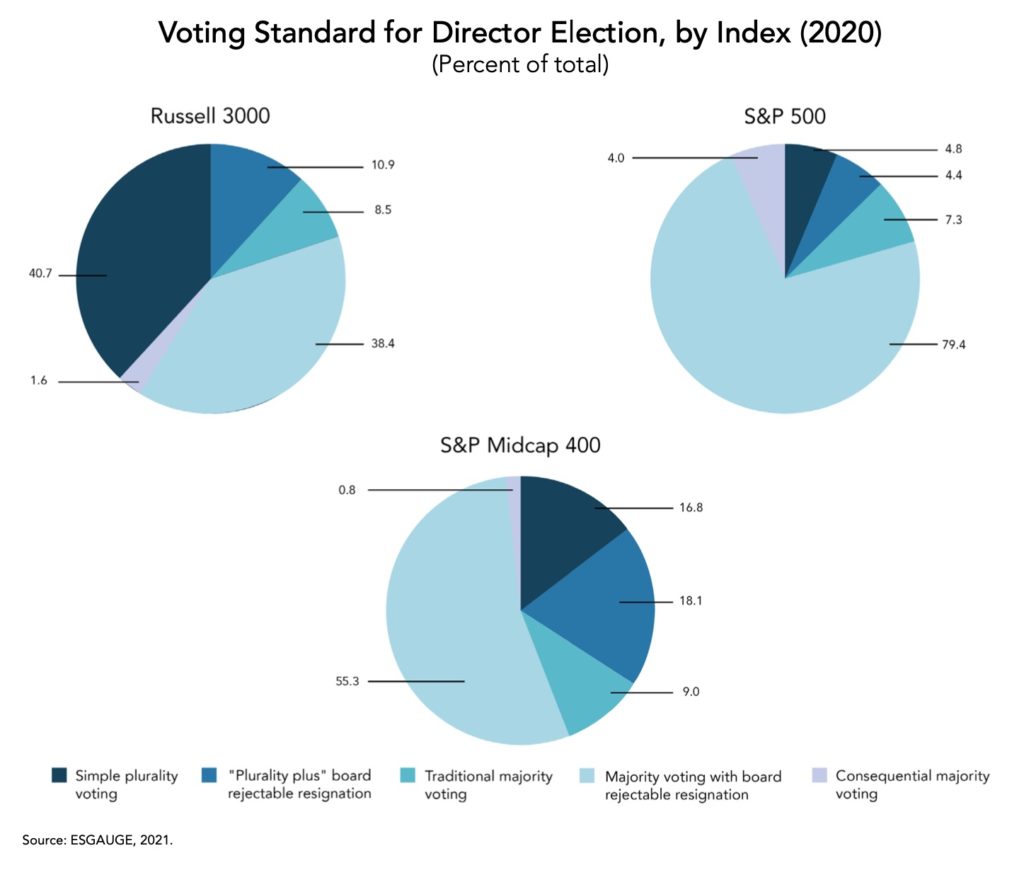

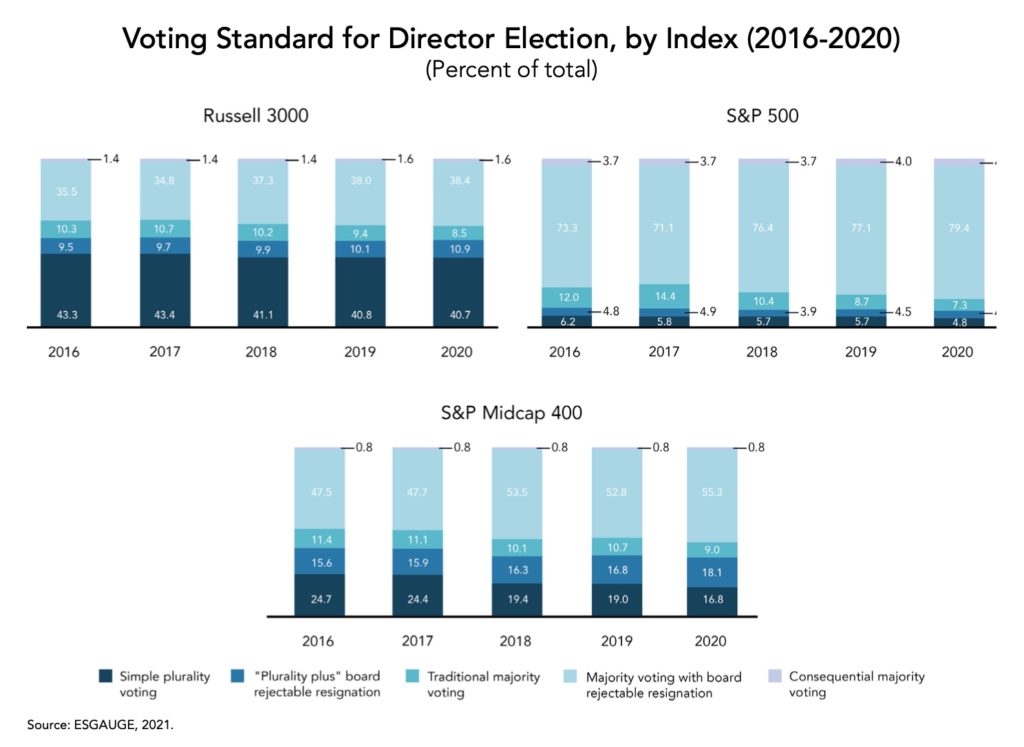

Voting standards for director elections also differ greatly depending on the size of the company. The main choice is between a plurality voting standard (where uncontested nominees who receive the most “for” votes are elected to the board until all board seats are filled, even if a majority of shares are voted against those individuals) and a majority voting standard (where a director generally loses her seat if she receives more against votes than for votes). Though declining in popularity, a plurality voting standard remains the norm at many smaller companies. According to the latest disclosure, 51.6 percent of Russell 3000 companies still had some form of plurality voting system (whether the straightforward one or the “plurality plus” variation, where a director who did not receive the support of a majority of votes cast must tender her resignation to the board and the board may accept or deny that resignation). Some form of plurality voting is also found in 85.5 percent of Russell 3000 companies with annual revenue under $100 million and in 67.8 percent of those with annual revenue in the $100 million–$999 million bracket. By way of comparison, in the S&P 500, only 9.3 percent of companies continue to rely on plurality voting. Instead, more than 90 percent of S&P 500 companies have adopted a majority voting standard for uncontested director elections.

If we now take a look at how director election practices have changed over the last four years, once again the S&P MidCap 400 ranks as the most dynamic of the three examined. Since 2016, the number of companies with some type of majority voting bylaws has grown by 1.7 percentage points in the S&P 500, by only 1.2 percentage points in the Russell 3000, and by as much as 5.4 percentage points in the S&P MidCap 400.

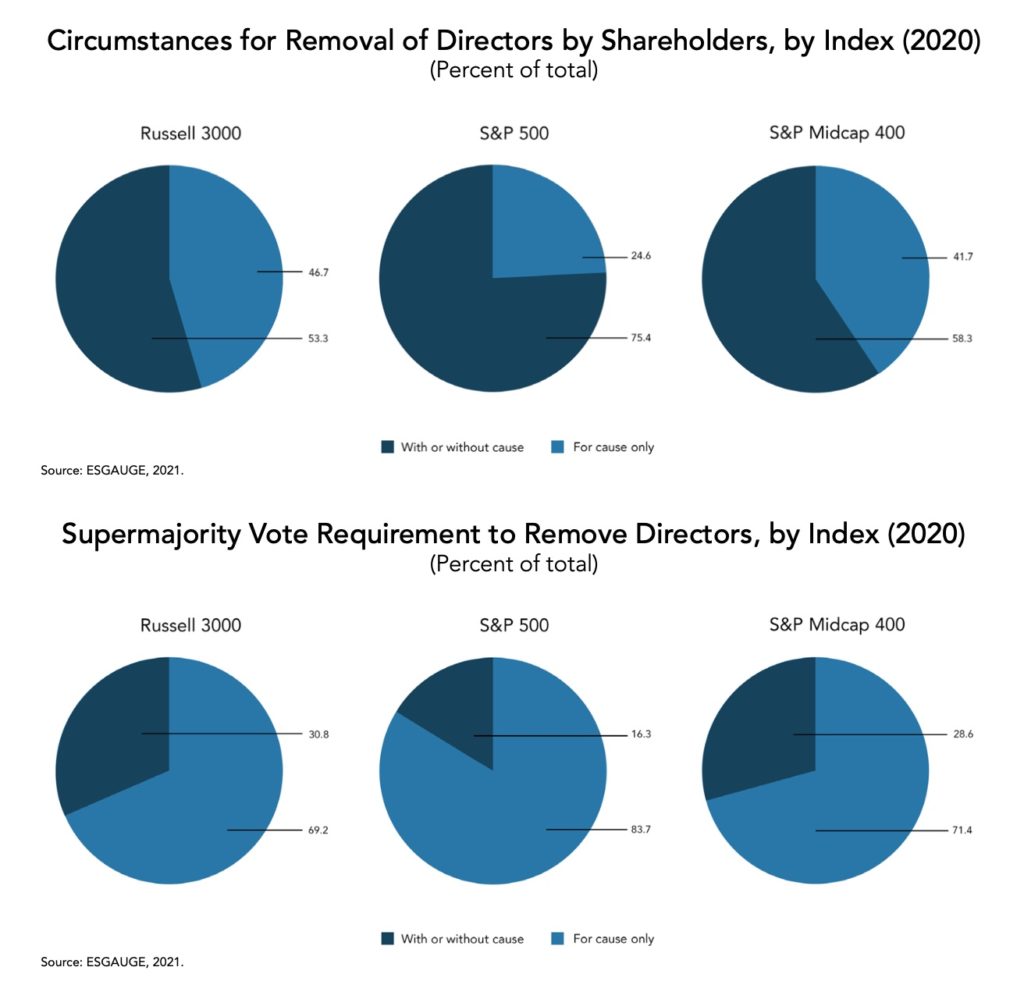

Our data also show that restrictions to shareholder rights are not always limited to the director election process and may extend to the right to remove directors. Under most state laws, shareholders representing a majority of shares entitled to vote at an election of directors may remove any director even without cause, unless the company has a classified board or allows cumulative voting. However, several companies with recently declassified boards still retain old charter provisions restricting shareholders’ authority to remove directors to situations where there is a “cause” of removal (e.g., unethical behavior, recurring absence from meetings, or other violations of corporate policies). In fact, this restriction is present in almost half of Russell 3000 companies, though only a quarter of S&P 500 companies and only two-fifths of S&P MidCap 400 companies. Where shareholders do have the authority to remove directors, almost a third of the Russell 3000 require some form of supermajority vote to accomplish this.

What’s ahead? As discussed above, board composition and director succession planning have become priorities for investors, amid renewed scrutiny of the effectiveness of board oversight [27] and rising demands for board diversity.

Companies that retain plurality voting and/or staggered board structures may be targeted by activists if it becomes apparent that their election process shuns shareholder rights or impairs board refreshment and diversity. They may consider the following developments:

- Shareholder proposals on board declassification and to repeal supermajority vote requirements have been the most successful governance-related proposal types in recent proxy seasons. In the January 1-June 30, 2021 period, all proposals of these kinds that were brought to a vote at Russell 3000 companies (24 in total, mostly targeting smaller companies) received ample shareholder support and passed. The same 100 percent success rate was recorded for resolutions on board declassification that were voted during any of the last three proxy seasons. [28] Today, many large institutional investors expect director elections to be held annually, to avoid entrenchment and promote refreshment. [29] Unless there is a specific justification for it, such as the need for stability during a strategic restructuring or the immediate post-IPO phase of a newly public company, the classified board structure is often red flagged as a governance shortcoming. [30]

- Similarly, as pension funds and other institutional investors embark in stewardship campaigns to promote board diversity and ESG oversight, they increasingly appreciate majority voting as a tool to hold directors accountable and curb inaction. After years of decline, the number of shareholder resolutions calling for majority voting has risen again in the last few proxy seasons and proponents are shifting their attention to smaller public companies outside of the S&P 500. Investors filed 16 such resolutions in 2021, up from only six in 2018; of those, 10 went to a vote and three passed (at Redfin Corporation (NASDAQ: RDFN), Axon Enterprise Inc. (NASDAQ: AXON) and Sonoco Products Company (NYSE: SON)). Ending a few years of hiatus, since 2019 CalPERS has been resuming its push in this area and was the top proponent of these types of requests in 2021. To be sure, most of CalPERS’ success takes place outside of annual meetings: The fund reported that, in 2020, its private engagement led as many as 20 companies to agree to adopt majority voting standards. [31] At a minimum, businesses that still use plurality voting in uncontested elections should consider using their proxy statement and investor engagement efforts to explain the rationale for their choice.

- “Just Vote No” campaigns for the removal of directors are becoming more frequent. These campaigns are being mounted to express dissatisfaction with the company’s performance with respect to ESG goals—whether on climate change risk mitigation, DEI policies, or political spending disclosure. In 2018, only 27 directors in the entire Russell 3000 failed to receive the support of a majority of votes cast; in the 2021 proxy season, that number was 68. In 2018, 86 directors were reelected with less than 70 percent support level; in 2021, that number more than tripled, to 308. [32] While the typical target is the small-cap company, the case of the ExxonMobil board, which recently made headlines for losing three directors in a proxy fight initiated by a small 0.02% shareholder, is indicative of how real this risk has become, including among larger companies. That shareholder won because it made a persuasive argument on the future direction of the energy industry (including by releasing a scholarly white paper on the topic) and received the backing of several major institutional investors (including Vanguard, BlackRock and State Street, but also large public pension funds such as CalPERS, CalSTRS and the public employee retirement funds of New York State and New York City). [33] While it remains to be seen whether the ExxonMobil case will become the playbook for future ESG-driven proxy contests, underperformance on these matters would only be amplified by director election policies perceived to shield the board from shareholder demands and reduce its accountability.

- The process for contested director elections may be simplified in the near future, in favor of dissidents, if the SEC approves its proposed rules on the use of universal proxy cards in solicitations. In April 2021, the SEC has reopened the comment period on such proposed rules, which were first issued in 2016 and would require all duly nominated board candidates—both a company’s own nominees and any brought forward by dissident shareholders—to be listed equally on a single proxy voting card, whether physical or electronic. [34] In its proposing release, the SEC observed that it has become “aware of concerns that some company proxy statements had ambiguities and inaccuracies in their disclosure about voting standards in director elections.” For this reason, the Commission proposed additional amendments to voting standards that would be applicable to all director elections, including uncontested elections: Specifically, under the proposed amendments, all proxy cards would also need include an against voting choice instead of a “withhold authority to vote” option, where permitted by state law, or to disclose the effects of a withhold [35] In the making for several years, the reform of the proxy voting process is a priority for the SEC. Even in light of the position expressed by the Commission in the proposing release on universal proxy cards, companies should review their director election policies and practices and, if it is found that they could hinder shareholder rights, introduce the opportune changes.

Endnotes

1Consumers Are More Likely To Use Or Drop Brands Based on Racial Justice Response, Survey Finds, Wall Street Journal, May 6, 2021; Pinterest Employees Demand Gender and Race Equality, New York Times, August 14, 2020.(go back)

2See the last edition of this report for an overview of key initiatives by State legislatures and institutional investors: Matteo Tonello, Corporate Board Practices in the Russell 3000 and S&P 500: 2020 Edition, The Conference Board, Research Report, October 1, 2020.(go back)

3See Improving Corporate Governance Through Diversity Act of 2019, H.R. 5084—116th Congress (2019-2020), which passed the US House of Representatives on November 19, 2019. Also see the letter sent by the US Chamber-led group of organizations to the US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs on July 27, 2020.(go back)

4See Improving Corporate Governance Through Diversity Act of 2021, H.R. 1277—117th Congress (2021-2022). H.R. 1277 would require public companies to disclose annually information on the racial, ethnic, gender, and veteran composition of its board of directors (including nominees) and executive officers to the extent that information is voluntarily provided. The bill also would require public companies to disclose if their boards of directors have adopted plans to promote diversity. Under the bill, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) would issue three recurring reports, including one on the best practices for complying with the new disclosure requirements. Finally, the SEC would be required to establish an advisory group on diversity to study and report to the Congress on the diversity of boards of directors of public companies.(go back)

5Allen Smith, More Companies Use DE&I As Executive Compensation Metrics, SHRM, July 12, 2021.(go back)

6ESG Incentive Plan Metrics Screening Tool, ESG Advantage Benchmarking Platform, The Conference Board, July 2021.(go back)

7See Board Diversity Matrix Disclosure Requirements and Examples (including the Board Diversity Matrix Instructions), NASDAQ Listing Center, August 20, 2021.(go back)

8Disability:IN and the American Association of People with Disabilities Say NASDAQ’s New Board Diversity Reporting Rule is a Missed Opportunity for People of Disabilities, Disability:DI, Press Release, August 6, 2021.(go back)

9See TheValuable500.com for an updated list of companies that have publicly committed to putting disability inclusion on their business leadership agenda.(go back)

10See, among others, Why Diversity and Inclusion Matter, Catalyst, June 24, 2020.(go back)

11State Street Global Advisors Marks Third Anniversary and Progress of Fearless Girl Campaign, Press Release, State Street Global Advisors, March 5, 2020.(go back)

12Our Approach to Engagement on Board Diversity, Investment Stewardship Commentary, BlackRock, March 2021.(go back)

13Statement on Nasdaq’s Diversity Proposals—A Positive First Step for Investors, US Securities and Exchange Commission, August 6, 2021.(go back)

14NASDAQ Board Diversity Quotas Challenged in Federal Court by the Alliance for Fair Board Recruitment, Alliance for Fair Board Recruitment, Press Release, August 18, 2021.(go back)

15Senate Bill No. 826, October 2018, and Assembly Bill No. 979, September 2020.(go back)

16Meland v. Padilla, E.D. Cal., Case No. 2:19-cv-02288, April 20, 2020. Creighton Meland, Plaintiff, brought suit against Alex Padilla, then California’s Secretary of State, Defendant, now Dr. Shirley N. Weber, as a shareholder of OSI Systems, Inc.(go back)

17Meland v. Weber, US Court of Appeal, 9th Cir, D.C. No. 2:19-cv-02288, June 21, 2021.(go back)

18Every Other One: A Status Update on Women on Boards, Committee for Economic Development (CED), The Conference Board, Policy Brief, November 14, 2016.(go back)

19Sehirsh Siddiqui, The Critical Role of Board Oversight of ESG Matters, Corporate Counsel, March 2, 2021.(go back)

20According to a recent academic review of the credentials of more than 1,000 directors at large US public companies, 29 percent of board members had a relevant ESG background, even though such expertise is largely concentrated in the S (social) element of ESG. Twenty-one percent of directors have relevant S experience, compared to only 6 percent with governance (G) experience and 6 percent with environmental (E) experience. A fifth of directors on a board is sufficient to staff a committee, 6 percent is not. However, it is likely that those industries where additional standing or special committees are more common—namely, utilities and environment, real estate and investment/pension—will have more directors with the relevant skills. See Tensie Whelan, U.S. Corporate Boards Suffer from Inadequate Expertise in Financially Material ESG Matters, NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business, forthcoming, as posted on SSRN.com on January 11, 2021.(go back)

21Jason D. Schloetzer, Matteo Tonello, and Francine McKenna, CEO Succession Practices in the Russell 3000 and S&P 500: 2021 Edition, The Conference Board, Research Report, June 2021.(go back)

22See United States Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations, Institutional Shareholder Services, November 19, 2020, p. 20.(go back)

23Matteo Tonello, 2021 Proxy Season Preview and Shareholder Voting Trends (2017-2020), The Conference Board, Research Report, January 2021.(go back)

24For the revisions, see Corporate Governance Principles, The Boeing Company, July 30, 2021; Corporate Governance Guidelines, Baxter International, November 16, 2020. In the case of Baxter, the revised governance guidelines clarify that the new board chair will be independent “unless the board determines that it would be in the best interests of the Company and its shareholders to have a non-independent director serve as Chair.”(go back)

25John R. Graham, et al., CEO-Board Dynamics, NBER Working Paper No. w26004, July 1, 2019.(go back)

26When a board is classified, directors are organized into two or three classes; each class faces election every two or three years. Under most state laws, the default rule provides for all directors to be elected annually. However, to make it more difficult for hostile or activist shareholders to gain control of the board, organizational documents (charters, initial bylaws, or bylaws adopted by a majority of shareholders) can prescribe the longer, staggered terms of a classified structure: in this case, the activist must win more than one proxy contest at successive shareholder meetings to elect a majority of the board members and exercise control of the target. See Lucian Arye Bebchuk, John C. Coates, and Guhan Subramanian, The Powerful Antitakeover Force of Staggered Boards: Theory, Evidence, and Policy, Stanford Law Review 54, 2002, p. 887.(go back)

27Survey: C-Suite Executives Say Boards Have Deep Understanding of the Business, But Could Be More Effective, Press Release, PwC, December 16, 2020.(go back)

28Based on data retrieved as a June 30, 2021 from Shareholder Voting Screening Tool, ESG Advantage Benchmarking Platform, Powered by ESGAUGE, The Conference Board/ESGAUGE, January 2021. Also see Merel Spierings, Matteo Tonello, and Paul Washington, 2022 Proxy Season Preview and Shareholder Voting Trends (2019-2021), Research Report, The Conference Board, forthcoming.(go back)

29During three academic years (2011-2012 through 2013-2014), Harvard Law School operated a clinic that assisted institutional investors (several public pension funds and a foundation) in moving S&P 500 and Fortune 500 companies towards annual elections. This work contributed to board declassification at about 100 S&P 500 and Fortune 500 companies. See Shareholder Rights Project, Harvard Law School, August 12, 2014.(go back)

30See BlackRock Investment Stewardship, Proxy Voting Guidelines for U.S. Securities, BlackRock, January 2021, p. 7. A classified board structure may also be justified, in certain circumstances, at public non-operating companies (e.g., closed-end funds or business development companies (BDC—a special investment vehicle designed to facilitate capital formation for small and middle-market companies). BlackRock would, however, expect boards with a classified structure to periodically review the rationale for such structure and consider when annual elections might be be appropriate.(go back)

31Simizo Nzima, Proxy Voting & Corporate Engagement Update, CalPERS, March 15, 2021, p. 3.(go back)

32Based on data retrieved as a June 30, 2021 from Shareholder Voting Screening Tool, The Conference Board/ESGAUGE, Id.(go back)

33ExxonMobil Loses A Proxy Fight With Green Investors, The Economist, May 29, 2021. Also see See Rusty O’Kelley and Andrew Droste, Why ExxonMobil’s Proxy Contest Loss Is A Wakeup Call for All Boards, Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, July 5, 2021.(go back)

34SEC Reopens Comment Period for Universal Proxy, Press Release, US Securities and Exchange Commission, April 16, 2021. The rule proposal also requires company and dissidents to notify each other of their respective nominees. Dissidents would be expected to solicit at least a majority of the voting powers of shares entitled to vote. Initially proposed in October 2016, the rules underwent a first comment period until the beginning of the following year. The reopening release requests comments on, among other things, whether dissidents should be required to solicit more than a majority of the voting power of shares entitled to vote, as was proposed in 2016.(go back)

35SEC Release No. 34-79164 (Universal Proxy), US Securities and Exchange Commission, October 26, 2016. In addition, under the proposed amendments to Rule 14a-4(b) under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, when the election is governed by a majority voting standard, shareholders that neither support nor oppose a nominee should be given the opportunity to abstain, as opposed to withholding authority to vote.(go back)

Print

Print

One Comment

Another thing coming is the disclosure of EEO-1 reports to the public. Companies are already collecting. Those who disclose now will get ahead of the game and are likely to be those with lower discrimination rates.