J.B. Heaton is a managing member of One Hat Research LLC.

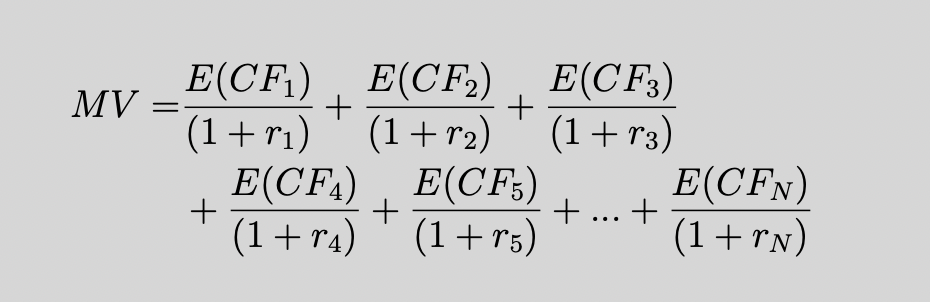

The goal of discounted cash flow (DCF) valuation analysis is to answer the question, “What is this asset worth?” as in, what is the price that a rational person would be willing to pay for this asset in a competitive asset market. It is a question to which good answers are often needed. The DCF valuation model is a hypothesis about the answer: market value (MV) equals the sum of the discounted expected future cash flows that the asset will provide to its owner:

where E(CFi) is the expected cash flow at future time i, ri is the discount rate for cash flows to be received from this asset at future time i, and N is the number of dates where cash flow is expected to be received. The cash flow expectations and discount rates are those of the equilibrium asset buyer who competes with other potential buyers facing—at least when the asset is fungible and has a perfect substitute owned by others—numerous potential sellers.

Economist Irving Fisher is credited with first suggesting in his 1907 book, The Rate of Interest, that any asset’s value is equivalent to the present value of its future income. Three decades later, J.B. Williams took a further step in his 1938 book, The Theory of Investment Value, asserting that the true value of a common stock could be calculated as the present value of its future dividends. In the early 1950s, Joel Dean proposed that capital projects could be evaluated by projecting future cash flows, discounting them to present value, and comparing present value to investment cost. It may have been Dean who first referred to this method by the term “discounted cash flow.” As financial economists got more precise about the theory of asset pricing, the theory of DCF valuation grew to encompass the assertion that market values were determined by discounted expected cash flows. Along with theoretical and empirical efforts to demonstrate that economic models could be used to estimate discount rates in the 1960s and 1970s, DCF valuation was, by the 1980s, in use for asset valuation and capital budgeting throughout the world by business financial analysts, stock analysts, investment bankers, and consultants.

DCF valuation “works” in one undeniable sense: a formula of the form

can “explain” any asset price. Equation (1) is a single equation expressing market value as a function of a large (potentially-infinite) number of variables. Because the right-hand side variables are unobservable expected values and discount rates, any known market value has a potentially-infinite number of DCF explanations. If, as is usually the case, the left-hand side market value is unknown and is calculated from the right-hand side of equation (1), then there are a potentially-infinite number of potential market values for any given asset, each with a potentially-infinite number of right-hand side choices of expected cash flows and discount rates.

But explanation is not prediction. What users of DCF valuation are nearly always interested in is an accurate prediction of the market value of an asset. The DCF hypothesis is not the trivial one that a single equation in potentially-infinite number of unknowns can generate any market value desired. Of course, it can. Users of the DCF valuation methodology—and consumers of its results—rely on the methodology’s ability to predict the value at which an asset would trade hands under some assumed market conditions. DCF valuation methodology, as presented in valuation texts and finance classes, says that if an asset with these expected cash flows and discount rates was offered in an asset market, then it would sell for such-and-such an amount.

The DCF Emperor Has No Clothes

Despite the ubiquitous use of the DCF valuation method, however, there is no evidence that it works for predicting the market value of capital projects, businesses, and common stocks. Apart from the inability to observe the inputs to the DCF calculation—expected cash flows and discount rates—we do not even have good reasons to believe that those quantities exist in any real sense.

It may come as a surprise to those who learned these methods in business school or are told by such people that DCF is a reliable tool that not one of its assumptions has good evidence behind it. There is no compelling evidence that real investors decide what to pay for assets whose future cash flows are not specified by contract (as with bonds or annuities) by discounting their “expected’” future cash flows in a linear fashion, no compelling evidence that investors form expectations of a series of future cash flows in the way theory assumes, and no compelling evidence that discount rates of the kind assumed in theory exist in any real sense, much less that we know how those imagined discounts would be determined. Indeed, there is compelling evidence against every one of the three reasons necessary to the reliability of DCF.

What About Bonds?

When I ask fellow financial economists what evidence they would point to if asked whether DCF works, they come up with only one answer: bonds. Bonds do lend themselves to a DCF interpretation, of course, but only because they have contractually-specified cash flows that can be matched to an observed price. Default-free bonds with observed prices can thus be interpreted as satisfying the DCF valuation methodology, but only because the relevant equation is then one in a single unknown, the yield-to-maturity which, for default-free cash flows, equals the expected return over the life of the bond. But the bond analogy breaks down quickly when bonds bear default-risk, since bond interest and principal repayment then become uncertain and the yield-to-maturity is no longer equivalent to an expected return.

Projects, Businesses, and Stocks Are Not Bonds

Unlike bonds, capital projects, businesses, and common stocks do not promise fixed cash flows and usually have uncertain longevity. We can always fit a given market value—say, for the stock market capitalization of public corporation—to a discounted cash flow expression, but that expression will be one of an infinite set of possible combinations of expected cash flows and discount rates. Competing models cannot be distinguished after-the-fact because there will be an infinite number of realized cash flow paths and time-varying discount rates that are consistent with any given expected cash flow and discount rate assumption at the time of modeling. The untestable nature of the DCF valuation method explains why there is almost no work even purporting to test the method. One exception, Kaplan and Ruback, The Valuation of Cash Flow Forecasts: An Empirical Analysis, Journal of Finance, 50(4), 1059-1093 (1995), illustrates the problem well, “testing” DCF by fitting known deal prices in highly-leveraged transactions to disclosed cash flow forecasts. But that is akin to the default-free bond, especially given the incentive to match deal prices to cash flow forecasts.

DCF Angels on DCF Pins

The untestable nature of the DCF valuation methodology explains two interesting facts about the use of DCF in practice. First is the near-obsession in valuation texts with arcane methodologies for cash flow estimation and discount rate calculations. Lacking empirical results as to which cash-flow forecasting methodologies and discount rate estimations lead to the best predictions—impossible because DCF is untestable in its typical applications—financial analysts and appraisers instead debate endlessly about proper ways to convert accounting numbers to cash flow estimates, proper ways to calculate terminal values, and proper ways to estimate discount rates. Because DCF is untestable, these debates are merely contests of persuasion.

Second is that DCF’s wide acceptance is justified in a duplicative manner by appeal to its general acceptance. For example, the DCF methodology is used widely in business litigation. While courts usually require scientific and technical evidence to be based on methodologies that are testable and have known accuracy and precision, courts justify the use of DCF valuation on the basis of its general acceptance without inquiry into its scientific validity. Reported cases involving DCF valuation often involve the sort of battles of experts described above and are usually decided by little more than which expert persuades the judge, or by a judge that considers himself expert enough to decide on his own the methodological issue at hand.

Consequences of Untestability

The untestable nature of DCF combines with its wide use to generate two potentially troubling (and related) consequences for business decisions.

First, the essence of the DCF valuation is heavy discounting of long-term cash flows. Discounting of future cash flows so heavily means that many long-term investments will look bad relative to the cost of investment and projects that pay off very quickly, that is, in the short-term. This may bias corporate investment against some long-term investments in the corporate C-Suite and boardroom and among stock analysts. Contrary to the laments of many commentators, there is no reason to believe that the stock market discounts long-term investments too heavily relative to short-term investments. Indeed, we know from real-world data that investors seem quite willing to provide very low-cost capital to firms in return for the gains that arise when a few of those firms does extraordinarily well. But business decision makers who use DCF will often reject good long-term business projects simply because they assume the validity of the DCF theory and use its methods to select corporate investments.

Second, the DCF valuation methodology encourages the belief that corporate managers and financial analysts can make accurate predictions about cash flows several years into the future. There is no reason to believe that is true, and much reason to believe it is not. Worse, people tend not to make unbiased forecasts that are equally likely to be wrong in either direction, neither biased upward nor downward on average. Instead, evidence from research in psychology shows that people are excessively optimistic, believing that bad outcomes are less likely than they are. The combination of heavy discounting and optimistic cash flow forecasting combine in a noxious way. Business projects most likely to look good in a DCF analysis are those that are least likely to see their forecasts come to fruition, since the best-looking projects will be those with overly-optimistic cash flow forecasts. This makes the DCF valuation methodology a recipe for corporate disappointment. Fee-seeking investment bankers can generate intentionally-overly-optimistic cash flow forecasts to sell mergers and acquisitions that destroy corporate value at the acquiring company, transferring that value to target shareholders. It is worth considering whether an untestable valuation methodology helps explain the strong empirical result in corporate finance that mergers and acquisitions benefit only target shareholders and not acquiring firms.

Conclusion

Assuming that users of the DCF valuation method want prediction and not just explanation, we need to know not whether we can fit the DCF equation to an asset price (we always can) but whether there is a way to apply the methodology to reliably estimate—with some measurable rate of error—the market value that an asset would have under assumed market conditions. Without an answer, we have no basis for confidence that DCF valuations are anything more than quantitative narratives, “stories” about asset prices rather than scientific estimates. General acceptance is not enough. The same was true for thousands of years about astrology, a field most now consider unscientific because, as one author puts it, astrology “is not falsifiable: astrologers cannot make predictions which if unfulfilled would lead them to give up their theory.” One must wonder if the same is now true of those who apply the DCF valuation methodology.

The complete paper is available for download here.

Print

Print