Key findings

Introduction

Driven largely by market forces, business is in a third great wave of corporate governance evolution. This follows significant changes brought about over the last twenty years by the Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank Acts. This current wave is driving the modernization of long-standing governance practices, impacting how boards fulfill their decision making and oversight responsibilities. But the changes are also surfacing conflicts and discontent.

To explore how executives perceive board performance, PwC and The Conference Board conducted our third annual survey of more than 600 public company C-suite executives in the fall of 2022. This survey was augmented by a series of executive interviews to gain qualitative insights.

Most notably, there is a confidence deficit in the board’s ability to address key areas that appears to be growing. This widening confidence gap — increasingly evident in the year-over-year results — is only one key finding. But it’s a critical one. At a time when executives are looking for more input from their boards, many executives lack confidence in their boards’ ability to ask probing questions or make decisions consistent with the company’s purpose and values.

The news isn’t entirely grim. Most executives view their board as effective in core oversight areas. But a disconcerting number see their boards as lacking diversity and specific expertise, slow to replace underperformers and insufficiently engaged.

How can directors and executives move forward together to enhance both the governance process and shareholder value? The board of the future needs to:

- Become a less reactive or passive oversight body and more of a strategic advisor to management.

- Improve the mix of skills, knowledge, experience and backgrounds to align more closely with the company’s strategic direction.

- Increase understanding of and engage more effectively with the company’s various stakeholders to further build and maintain trust.

- Use the information they receive from management to engage in more strategic and robust dialogue, pose tough questions and appropriately challenge.

Our research, bolstered by findings from PwC’s 2022 Annual Corporate Directors Survey, indicates that there are significant differences in how board members evaluate their own performance compared to how executives evaluate board performance. The research also identifies key opportunities for boards to boost their effectiveness and value. Making these improvements will require an evolution in the way boards and management work together, and for both directors and executives to acknowledge their own blind spots.

Board blind spots

Risk oversight

Blind spot

Most executives believe their boards understand key business risks and devote sufficient time to risk oversight. But executives are unsure of whether their boards add value in overseeing today’s increasingly complex and ever evolving risk landscape.

- Only 45% of executives say their boards have good risk management expertise.

- But 95% think their boards give sufficient attention to risk management.

- And 72% think their boards have a good understanding of their companies’ key business risks.

How to address

The board’s oversight of risk starts with an objective review of management’s process for assessing and mitigating risks. To help deepen the board’s discussion of the company’s key risks and risk management process specifically:

- Executives can integrate discrete, emerging risk areas into their existing board briefings on the company’s enterprise risk management (ERM) program.

- Boards can ask how management is integrating these risk areas into the company’s overall ERM process, and then align on the best approach to overseeing those risks.

- Management can also provide directors with greater educational opportunities, both during and outside of meetings, to deepen their fluency in ERM as well as emerging risk areas.

Digital transformation

Executives question the ability of their boards to effectively oversee technological transformation:

- 50% say their boards do not adequately understand the impact of digital transformation or emerging technology on their companies’ businesses.

- 30% say their boards have poor technology expertise.

Most current C-suite executives and directors aren’t digital natives, raised in the era of cloud and smart technology. Yet many companies’ futures depend on not only getting to the cloud but reinventing themselves there. That requires both management and the board to align on, believe in and execute transformation efforts to drive a different future.

Not every director possesses a deep understanding of technology, but boards must nonetheless oversee digital transformation and hold management accountable — confirming management is effectively linking digital transformation to strategy, setting milestones for execution, making sure the right talent is involved and developing KPIs to measure success. Management should help the board:

- Understand broader trends in digital technology and consumer behavior that affect the company’s business and industry.

- Be familiar with how the digital transformation is affecting the company’s competitors, suppliers and customers.

- Draw lessons from the digital transformation in adjacent industries.

Corporate purpose

Blind spot

Research has confirmed that consumers and employees are more likely to buy from or want to work for companies that share their values. Leading companies see the value of articulating their purpose and values through their ESG or sustainability strategy, as a business imperative and as a key differentiator. During times of crisis or uncertainty, corporate purpose can be a unifying source to inspire not only senior leaders and board members, but also employees, investors, customers and other stakeholders. [1]

- But 50% of executives do not trust their boards to make decisions consistent with their companies’ purpose and values.

How to address

The threshold requirement is that the board and management reach consensus on the company’s purpose — that is, why it exists — along with its mission (what it does) and its values (how it conducts itself). Those baselines can provide key guidance for the board and management as it sets its strategy and sorts through which ESG issues are of utmost importance. Once a company has a clearly defined purpose specific to it, management can ensure the board puts its purpose into practice by noting how significant board decisions advance (or do not advance) that purpose.

Board effectiveness

With companies facing new and rapidly evolving strategic challenges and business risks, today’s board oversight responsibilities extend well beyond traditional areas. This expansion may be impacting management’s perception of board effectiveness.

Boards continue to perform well in the traditional areas of oversight like corporate strategy. But companies are revisiting and revising their strategies to address the digital and sustainability transformations for their industries and firms. Board efficacy in these other areas of oversight has room to improve.

Directors’ grasp on key areas of oversight is mixed

More surprising and concerning, across many key areas of board oversight, more executives reported that their boards do not understand certain areas at all compared to last year’s survey.

- Shareholder priorities: 24% of executives say their boards do not understand shareholder priorities at all.

- Executive compensation: 20% of executives say their boards do not understand their company’s executive compensation plans and incentives at all.

Some directors struggle with understanding executive compensation plans

Percentage of executives who say their directors do not understand their company’s executive compensation plans and incentives at all

Executives rate overall board performance as middle of the road

Overall, executives think their boards are doing a fair or better job — but only 29% of executives rated their boards’ overall performance as excellent or good, which is consistent with last year.

Survey results also suggest that large company (revenue of more than $10 billion) executives are increasingly critical of overall board effectiveness. Their positive ratings are declining while negative ratings are increasing year over year.

Executives at larger companies are increasingly critical of board effectiveness

60% of executives don’t trust their boards to effectively self-assess their own performance

Closing the gap: What can boards and management do?

- Broaden the board’s role in the oversight of strategy: There is an opportunity to take areas that were once considered the concern of management, or perhaps a single board committee, and now integrate them into the full board’s discussion of strategy. For example, corporate strategy increasingly incorporates human capital management, climate, cybersecurity and data privacy — and management is integrating KPIs to monitor company performance on each. Increasingly, setting and overseeing corporate strategy requires an understanding of these business issues.

- Evaluate the allocation of responsibilities between the board and its committees: This can expose gaps in the board’s charter or governance policy and its committee charters, identify the need for a new committee to pick up responsibilities from an overburdened one or help consolidate related topics currently spread across committees.

- Conduct robust board and committee self-assessments – Rigorous assessment often includes:

- Asking management for input during self-assessment processes: This can advance the sense of shared responsibility for the company. Often executives can offer actionable insights that can improve committee or board performance.

- Leveraging results to make and track action plans

Board composition

Executives are keen on refreshing their boards

Board refreshment is more than just bringing fresh perspectives into the boardroom. If done effectively, it means evaluating and aligning the mix of director experience, skills and backgrounds needed to add value to the board’s oversight of the company in the coming years.

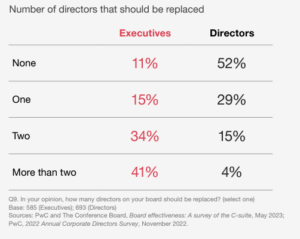

Consistent with last year’s survey, 89% of executives suggest that at least one of their directors should be replaced. Strikingly, 41% of executives suggest that more than two should be replaced.

The C-suite’s appetite for board turnover exceeds that of directors

The need for board refreshment may be accelerating — or may have just become more evident to executives. As issues such as ESG, climate, cybersecurity and human capital management become more central to business strategy, executives may increasingly see the need for directors that are better able to address these and other emerging issues.

For their part, directors cited two quite different reasons for wanting board refreshment: peers’ unwillingness to challenge management and the tendency to overstep the role of director. Both reasons relate to boards’ own ways of working as well as how boards and management work together.

Getting to “refreshment” can be difficult as nearly two-thirds of executives (64%) do not trust their boards to remove underperforming directors.

Board diversity is steadily increasing, but executives think there is a long way to go

Board diversity has increased slowly during the past decade, due to a variety of factors from disclosure requirements to investor, consumer and other expectations. Commitment to increasing board diversity over the past two years is evidenced in PwC’s 2022 director survey: 67% of directors say their boards replaced a retiring director with one that increased the board’s diversity, and 36% of directors report that their companies had increased board size to add a diverse director.

But executives believe that work remains to be done in recruiting and onboarding new and diverse directors.

Executives want increased board diversity, but are not seeing enough change

60% trust their boards to prioritize board diversity

But only 20% think their own boards are diverse enough

66% cite long-tenured directors’ reluctance to retire as the top reason for lack of board diversity

Closing the gap: What can boards and management do?

- Conduct individual director assessments. Individual director assessments can help current directors identify their own strengths and weaknesses, boost contributions and understand how peers perceive them. The results can form the basis for customized development plans and follow-up — or exit of underperforming board members.

- Ensure board leadership is up to the task. Consider whether the board’s current chair, lead director or governance committee chair is thinking strategically about the board’s refreshment needs and is willing and able to have what could be hard conversations with individual directors who need to improve their performance.

- Prioritize diversity. To broaden the board’s profile, director recruitment efforts need to go beyond standard sources of candidates and criteria. Boards should be mindful that diversity has multiple dimensions, including demographics, professional skills or expertise, management experience, board experience, personal backgrounds, and cognitive approaches and attitudes, such as risk tolerance. Boards naturally tend to consider these factors when recruiting new board members but may not be explicit about the multiple dimensions of diversity or what they are looking for in terms of cognitive diversity.

- Reconsider board size. Directors could increase the board size to allow room to add diverse members with new experiences and perspectives.

Board engagement

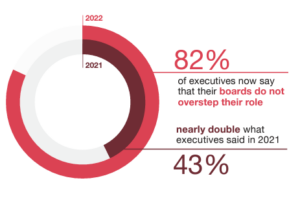

Executives say their boards are operating at the right level…

The dramatic increase in executives who say the board is not overstepping its role may reflect management’s appreciation for the board’s increased workload and scope of responsibilities due to heightened investor and constituency expectations, increased regulatory requirements, and an increase in the number and complexity of areas of board oversight. At the same time, the board’s increased remit may result in the board not having the time or knowledge to challenge management as effectively as in the past.

But question whether they are being effectively challenged

Only 33% of executives say their boards ask probing questions, suggesting that executives are worrying less about directors staying in their lane than whether the board is adding value by challenging management.

There is a disconnect in what executives say about the board’s time commitment and preparation

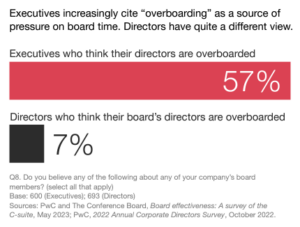

Are directors over-committed?

Executives increasingly cite “overboarding” as a source of pressure on board time. Directors have quite a different view.

What constitutes overboarding? A good starting point for that determination is the various policies of the company’s investors. In recent years, that generally has been four or five boards for non-executives and one or two outside boards for sitting executives.

Do boards have too much on their plate?

During the pandemic, boards met more frequently — focusing on pandemic-related topics and impacts. But indications are that meeting frequency and length are returning to normal.

Yet the number and complexity of topics requiring oversight continues to increase, making it harder to allocate adequate meeting time and attention to each. A too heavy or poorly prioritized agenda can leave too little time for robust discussion and probing questions. In PwC’s 2022 Annual Directors Survey, directors themselves lament a lack of time and overly packed agendas. In fact, directors noted several oversight areas that they feel currently receive insufficient board attention, including strategy (37%), talent management (33%) and cyber/digital/technology (26%).

Closing the gap: What can boards and management do?

- Prioritize the board’s work. It is important for the board’s meeting schedule and agendas to not be driven merely by regulatory requirements and the corporate SEC and financial reporting cycle. It should reflect, and vary in accordance with, the company’s strategic priorities and key risks. It is helpful for management to propose, and the board and committees to approve, annual work plans and individual meeting agendas designed to achieve those goals.

- Be transparent about board priorities and activities. If the board is transparent with management about its priorities and how it wants to spend its time, management can better support the board in achieving its goals. Also, because management is not present in executive sessions, boards must make those sessions effective and, as appropriate, inform management of topics discussed, any management follow-up needed and actions taken.

- Evolve the “ways of working.” During the pandemic, more frequent and less structured discussions between the board and management became the norm — and best practice. This approach can create a more collaborative dynamic in board meetings, leading to more valuable exchanges.

- Support appropriate and effective challenge through board materials. Management should provide the board and committees with materials far enough in advance to allow directors time to read and digest the information and frame effective questions. They should also be sure to highlight the areas of risk, opportunity and uncertainty for the matters that will be discussed, and identify where the board’s judgment would be especially helpful.

- Be candid with directors about director time commitment. When recruiting new directors, be candid and realistic about the time required to serve on the company’s board. During the board assessment process, address the time commitment holistically, going beyond the number of boards that they sit on to discuss the full breadth of their responsibilities.

Board expertise

Executives give boards high marks for knowledge and expertise regarding the more traditional areas of board oversight

We theorize that this sentiment is because companies tend to have mature and structured processes for reporting to the board on these areas.

Executives give their boards fair grades on cybersecurity and data privacy knowledge and expertise

But directors give themselves much higher marks

Ninety percent of directors think their boards understand cybersecurity and data privacy at least somewhat well. And more than 90% are comfortable that their companies are staying current on cyber defenses, have identified their most valuable digital assets and have done enough attack resistance testing.

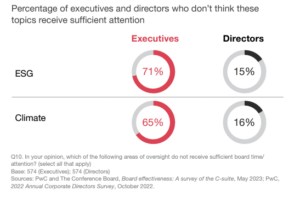

Building understanding — ESG and climate

Executives and directors also disagree about the board’s commitment to, understanding of, and expertise in ESG and climate.

Executives don’t think ESG and climate receive sufficient board attention — directors disagree

Executives and directors are more aligned on the board’s understanding of ESG

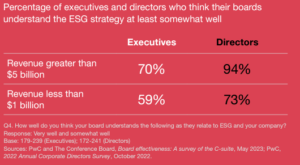

Company size matters when it comes to how well executives and directors think their boards understand ESG strategy

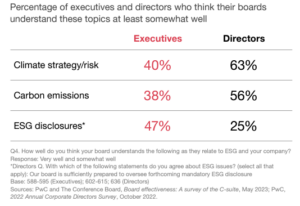

Executives and directors think their boards understand less about climate

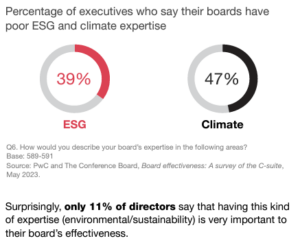

There is also a perceived lack of expertise across ESG and climate

Closing the gap: What can boards and management do?

- Improve board reporting. While management spends all day immersed in company information, directors don’t. Management must be thoughtful about the quality and quantity of information it provides directors to enable robust discussion and informed advice and decision making at board meetings. Management should also work to avoid presenting information with the goal of reassuring directors, rather than surfacing issues for discussion.

- Promote board education. While directors can take ownership of their upskilling by attending relevant seminars and reading more broadly, general director education is not, of course, company specific. Management can help. Every meeting and every board or committee discussion is a board education opportunity to address risk and crisis management in the context of the company’s business. For example, management should provide deep dives into the company’s top cyber risks and mitigations.

- Encourage more informal director interactions. Less-structured one-on-one or small group conversations can sometimes allow executives to better assess the director’s understanding of issues and offer executives an opportunity to share knowledge with directors.

- Be intentional about board refreshment and recruitment. A comprehensive assessment of board composition — comparing the totality of skills to the company’s needs in the coming five to 10 years — can help the board identify the gaps it needs to fill. Based on that assessment, the board can recruit new and diverse directors with expertise in these areas, especially in industries where cybersecurity and climate have become larger strategic concerns.

Connecting the dots to overall board performance

There appears to be a positive correlation between executives’ views on overall board effectiveness and how executives view their board’s composition, level of engagement, knowledge and expertise. At least 75% of executives who either think their board has sufficiently diverse backgrounds or skills, asks probing questions or spends sufficient time doing its job, also ranked their board’s overall effectiveness as either excellent or good.

However, only 32% of executives who think their boards do not overstep their roles rank their boards’ overall effectiveness as either excellent or good.

Stakeholder engagement

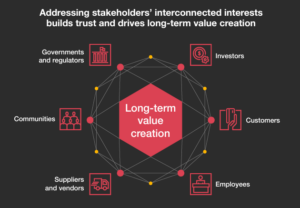

One board, many stakeholders — engaging and building trust

Not long ago, boards had relatively little engagement with shareholders. As the frequency of director engagements with investors has grown in recent years, so have demands. The bottom line has remained constant: Effective engagement is built on understanding and trust.

Management’s view of director engagement with shareholders reveals disconnects

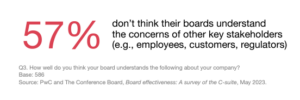

And executives are even less confident in director engagement with other key stakeholders

Closing the gap: What can boards and management do?

- Embrace multi-stakeholder governance. Before management and boards can take all appropriate stakeholders into account in planning and decision making, they need a framework to identify, understand, prioritize and address the sometimes-competing interests.

- Increase stakeholder understanding and engagement. To boost management’s confidence and prepare directors for effective engagement with all key stakeholders, management might consider: –

- Providing the board with periodic updates regarding the company’s varied stakeholders, and their priorities and policies. This should include information about the evolution and composition of the shareholder base.

- Developing a strategy and framework for stakeholder engagement and director involvement in those engagements.

- Briefing directors regarding likely stakeholder engagement topics.

- Adopting a written policy governing director-stakeholder engagement, to identify for directors, management and stakeholders the circumstances in which stakeholders should reasonably expect access to directors, the process for stakeholders to request director engagement, and how executives and directors will prepare for those engagements.

- Incorporate stakeholder information into key decision making. It is important to include stakeholder views or impact as part of the company’s key decisions (e.g., M&A). Management should build this information into board briefing materials.

Conclusion: A way forward

Effective corporate governance requires that management and boards develop new ways of working as the business landscape continues to shift. Directors are responsible for key decisions and oversight, but they cannot fulfill that responsibility without becoming more of a strategic partner with the C-suite. Building that stronger partnership can benefit companies over the long term.

In the final analysis, executives believe their boards are doing “okay,” but there is room to do better. Improving the board’s mix of skills, knowledge, experience, diversity and backgrounds to align more closely with the company’s strategic direction can enhance board effectiveness. In addition, increasing board understanding of, and promoting engagement with, the company’s various stakeholders can build and maintain needed trust.

Getting back to some of the basics and focusing on foundational governance can boost overall effectiveness even as boards seek ways to better address today’s and tomorrow’s challenges. Management must support the board, fully joining the directors in that evolutionary journey.

Download the complete report here.

Endnotes

1 See John Metselaar, How Company Purpose Can Guide the Board in Times of Crisis, The Conference Board, March 16, 2022. The 2023 edition of The Conference Board’s C-Suite Outlook report revealed that CEOs of US companies consider a pressing priority to revisit the mission and purpose of their organization; see Charles Mitchell, et al., On the Edge: Driving Growth and Mitigating Risk Amid Extreme Volatility, The Conference Board C-Suite Outlook 2023, January 12, 2023.(go back)

Print

Print