Yu An is an Assistant Professor of Finance at Johns Hopkins University, Matteo Benetton is an Assistant Professor of Finance at the University of California, Berkeley, and Yang Song is an Associate Professor of Finance at the University of Washington. This post is based on their recent paper, forthcoming in the Journal of Financial Economics. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Index Funds and the Future of Corporate Governance: Theory, Evidence and Policy (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian Bebchuk and Scott Hirst; New Evidence, Proofs, and Legal Theories on Horizontal Shareholding (discussed on the Forum here) and Horizontal Shareholding (discussed on the Forum here) both by Einer Elhauge.

Introduction

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) have experienced remarkable growth in recent years. According to the 2021 Investment Company Institute Fact Book, total assets under management (AUM) in ETFs increased from $992 billion in 2010 to $5.4 trillion by the end of 2020.

By design, the vast majority of ETFs passively replicate the performance of an underlying index, which in most cases is constructed and maintained by a designated index provider. As S&P Dow Jones, the world’s largest index provider, writes on its website, “An index provider is a specialized firm that is dedicated to creating and calculating market indices and licensing its intellectual capital as the basis of passive products.” Thus, most ETFs exhibit a two-tiered organizational structure: (i) an index provider builds and maintains the index that underlies an ETF and charges index licensing fees to an ETF issuer, and (ii) the ETF issuer services ETF investors and charges expense ratios to ETF investors.

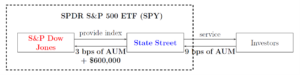

Figure 1: Two-tiered organizational structure for SPDR S&P 500 ETF as of December 2020.

Figure 1 illustrates the two-tiered organizational structure for the largest ETF in the world, the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY), as an example. In this case, the ETF issuer is State Street, and the index provider is S&P Dow Jones, which owns the underlying ETF index—the S&P 500 index. State Street charges SPY investors 9 basis points (bps, one basis point is 0.01%) per year and in turn, pays 3 bps of the ETF assets plus a flat fee of 600,000 per year to S&P Dow Jones. In other words, more than one-third of SPY’s total revenue is paid to the index provider as index licensing fees. For example, the SPY AUM totaled about $400 billion in 2021, implying that the total fees collected by State Street from SPY investors were roughly $360 million in 2021, with more than $120 million paid to S&P Dow Jones in index licensing fees.

$120 million per year seems a significant amount of money for a seemingly simple task of computing indexes. Motivating by this simple evidence, we ask three questions:

- Are high index licensing fees special to the SPY ETF, or is it a general feature of the indexing industry?

- Are high index licensing fees due to the high cost of index provisions, or the high markup charged by index providers as a consequence of lack of competition?

- Do high index licensing fees hurt end ETF investors?

Main analysis

To answer the first question, we manually collect the first data on the licensing fees between index providers and ETF issuers by reading all ETF filings on the Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval (EDGAR) system of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Since licensing fees are disclosed by ETF issuers on a voluntary basis, only about 10% of ETFs in our sample disclose their licensing fees. Despite this limitation and possible selection bias, our novel data enable us to look into the black box of ETF index licensing fees.

Based on this best available information that we can obtain, we find that more than 95% of the licensing fees are imposed in the form of “percentage-of-AUM” fees, with the remainder applied as flat fees. In other words, index licensing fees are mostly tied to the assets of ETFs. We estimate that the index licensing fees comprise about one-third of all ETF expense ratios that ETF issuers collect from ETF investors. This fraction has also increased steadily over time, from 31.4% in 2010 to 35.7% in 2019.

Having established that licensing fees account for a major fraction of ETF expense ratios, we proceed to answer the second question using both reduced-form and structural analysis. The first reduced-form evidence is that the ETF indexing business is highly concentrated among a few large index providers. For example, about 53% of all ETF assets in our sample track the indexes built by S&P Dow Jones. The five largest index providers in the U.S. equity ETF market—S&P Dow Jones, CRSP, FTSE Russell, MSCI, and NASDAQ—capture in aggregate about 95% of the entire ETF market. Specifically, over our sample period from January 2010 to the end of 2019, the time-series average of the Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI) of the index provider industry is 3,294, which is deemed highly concentrated according to by the standard of the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission.

Second, we find that, when choosing among ETFs, investors care about the identities of index providers, although there is no material difference in return profiles between indexes that various index providers construct. Specifically, we find that index-provider fixed effects alone can explain about 21% of the variation in ETF assets. Even after controlling for ETF-issuer, time, and ETF-category fixed effects, expense ratios, and past returns, index providers can still explain 8% of the residual variation in ETF assets. In contrast, we find that the index-provider fixed effects have literally zero explanatory power for ETF returns. This finding is consistent with a brand value interpretation of index providers, where ETF investors choose indexes with more trustworthy brands or better recognition.

The reduced-form evidence supports the interpretation of a lack of competition among index providers. To provide a quantitative estimate, we build a structural model that incorporates the two-tiered competition among index providers for ETFs and among ETFs for investors.

Our structural estimation reveals several results. First, the key structural parameter shows that the index provider market is highly uncompetitive. Specifically, if index provider A can offer 1% higher profits for ETFs than index provider B, the probability that an ETF chooses index provider A is only 0.53% higher than the probability that the ETF chooses index provider B. In contrast, if index providers were perfectly competitive, index provider A should always be chosen over index provider B. Such a low elasticity implies very limited substitutability across index providers, which is consistent with persistent indexing relationships and significant market power wielded by index providers.

Second, we estimate that about 60% of index licensing fees are markups. In 2019, the estimated licensing fees were 4.4 bps of an ETF’s AUM on average, while the estimated marginal costs of index provision were about 1.6 bps on average. Hence, average markups are about 2.8 bps and the Lerner index (=markup/licensing fees) of index providers is about 63%, indicating that index providers charge very high markups for index provision. In comparison, we estimate that about 40% of the expense ratios that investors pay to ETF issuers reflect markups of ETF issuers.

Having established high markup and under-competitiveness of index providing markets, we proceed to answer the third question through our structural model. Specifically, we conduct two main sets of counterfactual analyses to understand the equilibrium effect of (i) entry by a new competitive index provider and (ii) increased elasticity of ETF issuers to index providers’ licensing fees. We find that the entry of a new index provider that charges low licensing fees is ineffective in promoting competition in the market, leaving equilibrium index licensing fees and ETF expense ratios almost unaffected. This result is consistent with limited effects from entry when the demand side is inelastic to prices and is captured by existing brands. Aligned with our findings, the launch of Morningstar’s “Open Indexes Project” in 2016, which aimed to provide low-cost substitutes for the major index providers’ equity indexes, had little effect on equity index licensing fees.

Next, we directly promote competition among index providers in our model. We find that, with perfectly competitive index providers, ETF marginal costs decrease by about 2.8 bps, and the ETF expense ratios decline by a similar amount, which represents a 30% reduction relative to the baseline scenario. In dollar amount, this decrease will generate approximately $700 million in yearly savings for ETF investors.

Ongoing regulatory investigation

Overall, our results show promoting competition among existing index providers could significantly benefit end ETF investors.

In fact, the Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) have recently called for studies about disclosure and competition in the index provision markets in the US and the UK (See, for example, https://www.sec.gov/rules/other/2022/ia-6050.pdf and https://www.ft.com/content/58946854-72b8-4c0d-9507-b9ec1c350a85) Our work is also cited in a recent SEC rule https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2022/33-11125.pdf

Relatedly, the licensing fee contracts are not disclosed publicly, which might contribute to the opacity of the index providers. A better disclosure mandated by the regulators could potentially help end ETF investors, academics, legal experts, and general public better understand this market. Of course, any such disclosure must be carefully designed to protect any confidential information and the benefits must be compared to possible disclosure/reporting costs.

Key takeaways

- Index providers change high fees for ETFs to use the indexes, which average about one-third of ETF expense ratios.

- The high indexing fees are largely driven by high markups charged by index providers, due to a lack of competition.

- Reducing the market power of index providers could significantly benefit end ETF investors through a reduction in expense ratios.

- Ongoing regulatory investigation are targeting the index provision market.

Print

Print