Geeyoung Min is an Assistant Professor of Law at Michigan State University. This post is based on her recent article published in the UC Davis Law Review.

Corporate compliance is at an inflection point, putting pressure on companies to reinforce their compliance programs more than ever before. Corporate policies serve as a blueprint for company-wide compliance programs, implementing compliance efforts into companies’ daily operations. Various internal and external factors have contributed to this increased formalization and disclosure of corporate policies, including the Department of Justice (DOJ)’s corporate enforcement policy, Caremark duties, shareholder proposals and litigations, and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)’s disclosure requirement. Corporate policies have evolved from relatively informal internal documents meant primarily for employees into critical sources of information for various stakeholders and government authorities.

Corporate policies are rules and regulations that companies create and enforce internally and are a prime example of private ordering. Existing literature on the roles and limits of corporate private ordering has focused mostly on corporate governance issues, and little is known about the interaction between regulatory compliance and private ordering. Given the predominantly mandatory nature of regulatory compliance, it raises fundamental questions: how much discretion do corporate managers use, and how much should they use in customizing compliance using corporate policies?

To investigate the exercise of discretion in crafting corporate policies, this article examines written, stand-alone corporate policies disclosed on S&P 500 companies’ websites on two important issues: insider trading and related party transactions. The analysis reveals that companies not only tailor internal procedures to conform to external regulations but also actively customize the scope of prohibited actions in their policies, particularly when legal ambiguity exists. They often push the boundaries of external regulations, either in stringent or lenient directions, depending on the issue at hand.

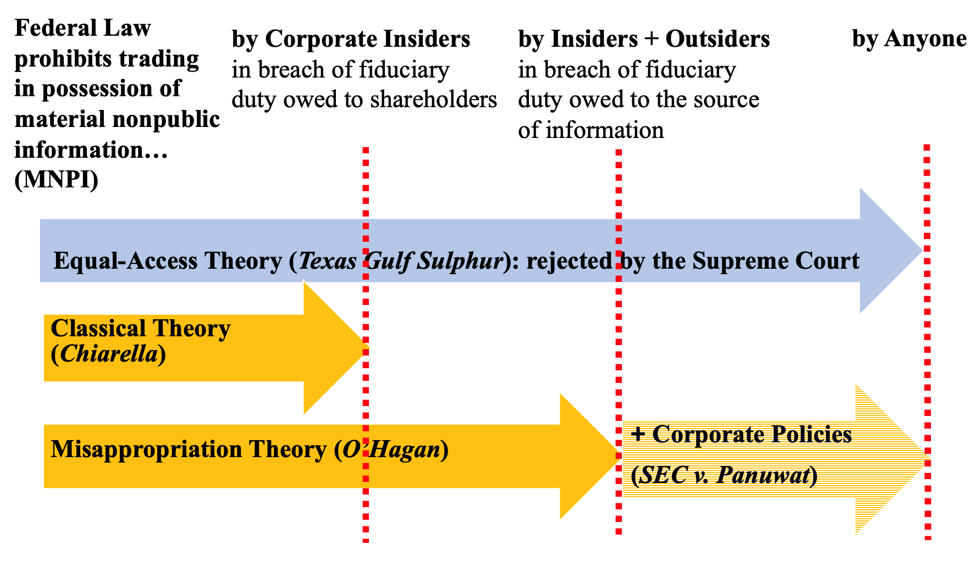

The first set of sample policies deals with insider trading — trading of securities using material, nonpublic information (MNPI). Insider trading is strictly prohibited under federal law, but what exactly the term “insider trading” entails is unclear because neither Congress nor the SEC has expressly defined it. Its definition has evolved mainly through federal common law, and companies tend to define prohibited insider trading in their corporate policies as broadly as possible. An analysis of the sample insider trading policies shows that such expansive insider trading prohibition is prevalent across companies. Approximately seventy-six percent of the disclosed, stand-alone insider trading policies from S&P 500 companies prohibit the trading of any other publicly traded companies’ stock based on MNPI.

Such broad prohibitions entail significant legal consequences, as exemplified in a recent case. In SEC v. Panuwat, the court said that the trading of a separate, third-party company’s stock could fall under the SEC’s “misappropriation theory” of insider trading, particularly because the trader breached the fiduciary duty to his employer by not complying with its insider trading policy, which prohibited insider trading more expansively than federal securities law does. As the trader would not have violated federal insider trading law if the corporate policy had not broadly defined insider trading, the case demonstrates how internal corporate policies can affect external regulators, courts, and other companies. The figure below graphically demonstrates this relationship.

On the other side of the spectrum, companies can also narrow the scope of prohibited actions, which makes corporate policies more lenient than the applicable external rules. Contrary to the trend among insider trading policies, eighty-one percent of sample related party transaction policies grant categorical waivers, narrowing the scope of prohibited transactions. For instance, if a transaction falls under the categorical exceptions predetermined by a company’s policy, a corporate insider does not need to disclose the transaction to the company. Such categorical waivers can create information blackouts on related party transactions, potentially undermining the cleansing mechanism under corporate law.

These findings reveal the divergence puzzle: why do corporate managers tend to relax internal policies on related party transactions while ratcheting up the scrutiny of insider trading?

The article explains why the prevalent theories in the business law sphere (agency cost theory and efficiency theory) cannot fully explain the divergence of stringency in corporate policies. While agency cost theory offers a plausible explanation for lenient policies, it does not clarify why corporate managers make insider trading policies stricter than required by federal securities laws. Furthermore, the agency cost theory does not account for the policy-to-policy difference within a firm, as corporate managers’ agency problem in tailoring the level of stringency will likely be consistent across various policies.

On the other hand, the efficiency theory will interpret the current variation in stringency as a result of the corporate managers’ quest to make the process more efficient for the firm and its shareholders. Despite such benefits, the efficiency theory tends to focus too heavily on procedural efficiency while disregarding substantive efficiency. This bias may underestimate the consequences of failing to screen harmful related party transactions. Also, this theory, similar to the agency cost theory, falls short of offering a satisfactory explanation. When we consider the harms inflicted by each underlying action, the policy-to-policy divergence becomes more puzzling. Setting aside the issues of external enforcement, related party transactions can directly harm companies, but insider trading impairs the integrity of the external securities market without necessarily directly harming the company.

The article introduces a complementary theory called “strategic compliance,” where companies strategically customize their corporate policies in response to the intensity of external enforcement rather than company-specific risks. Strategic compliance seeks to minimize liability risks by implementing stringent internal monitoring when external enforcement is robust and adopting lenient policies when external enforcement is weak. While not inherently problematic, it can lead to compliance failures in the long term by channeling firms’ compliance resources uniformly to areas with rigorous external enforcement, leaving certain other compliance areas unattended. Particularly when using categorical inclusion or exclusion in corporate policies, strategic compliance may impair effective coordination between external and internal monitoring. It can also undermine the regulatory goal of encouraging each company to implement the best-tailored policies responding to its own level of compliance risk. Thus, strategic compliance has potential benefits but also carries risks, emphasizing the need for a nuanced understanding of the evolving landscape of corporate compliance. The full paper, with more nuanced implications of the theory, is available here.

Print

Print