Lucian Bebchuk is Professor of Law, Economics, and Finance at Harvard Law School; Alon Brav is Professor of Finance at Duke University; Wei Jiang is Professor of Finance at Columbia Business School; and Thomas Keusch is Assistant Professor at the Erasmus University School of Economics. This post relates to a recent article, Hedge Find Activism and Long-Term Firm Value, by Cremers, Giambona, Sepe, and Wang, which was recently made publicly available on SSRN. This post is related to the study on The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, and Wei Jiang (discussed on the Forum here).

This post replies to a study by Cremers, Giambona, Sepe, and Wang (“the CGSW Study”), Hedge Find Activism and Long-Term Firm Value. The CGSW study, which has recently been publicly released on SSRN and simultaneously announced in a Wachtell Lipton memorandum, aims at contesting existing evidence on the long-term effects of hedge fund activism. As we explain below, the paper overlooks prior opposing evidence on the subject, offers a flawed empirical analysis, and makes claims that are contradicted by its own reported evidence. Furthermore, the paper’s conclusions are inconsistent not just with our work, but with a large body of empirical studies by numerous researchers. CGSW’s claims, we show, should be given no weight in the ongoing examination of hedge fund activism.

In a paper titled The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism, (“the LT Effects Study”), three of us tested empirically the “myopic activism claim” that has long been invoked by opponents of shareholder activism. According to this claim, hedge fund activism produces short-term benefits at the expense of long-term value. The LT Effects Study shows that the myopic activist claim is not supported by the data on targets’ Tobin’s Q, ROA, or long-term stock returns during the five years following the activist intervention.

CGSW focus on one part of the results of the LT Effects Study—those concerning Q (financial economists’ standard metric of firm valuation). Accepting that industry-adjusted Tobin’s Q improves in the years following activist interventions, CGSW assert that what has been missing is a comparison of how activist targets perform relative to a matched sample of similarly underperforming firms. CGSW claim that their matched sample analysis shows that the Q of activist targets improves less in the years following the intervention than the Q of matched control firms and that activism therefore decreases, rather than increases long-term value. Although CGSW do not look at stock returns, their conclusions imply that the announcement of an activist intervention represents “bad news” for investors that should be expected to be accompanied immediately or ultimately by negative stock returns for the shareholders of target companies.

Below we in turn comment on:

(i) Our obtaining different results than those reported by CGSW when applying CGSW’s empirical methodology to the same data;

(ii) The inconsistency of CGSW’s claims with some of their own reported results;

(iii) CGSW’s puzzling “discovery” of a well-known selection effect;

(iv) CGSW’s failure to engage with prior work conducting matched sample analysis and reaching opposite conclusions;

(v) CGSW’s flawed empirical methodology;

(vi) The inconsistency of CGSW’s conclusions with the large body of evidence on stock returns accompanying activist interventions; and

(vii) CGSW’s implausible claim that activist interventions have destroyed over 50% of the value of “innovative” target firms.

Although CGSW direct their fire at the Long-Term Effects Study, the discussion below explains that their conclusions are inconsistent not just with this study but with a large number of empirical studies by numerous researchers, including the many studies cited below.

CGSW’s Data and Results

The CGSW paper is based on a dataset of activist interventions that two of us collected and that the LT Effects Study used. Although we are still working with the data to produce additional papers, we agreed to provide the authors with our data to facilitate research in this area. To our surprise, the authors did not provide us an opportunity to comment on their paper before making their paper public, and we first learnt about the paper from Wachtell Lipton’s memorandum announcing it.

Although we view the empirical procedure used by CGSW as flawed, we have attempted to replicate their results using our data (which CGSW used), following the procedure described in their paper and making standard choices for elements of the procedure that the paper does not fully specify. Doing so, we have obtained results that are very different from those of CGSW.

We asked the authors to provide us with the list of the matched sample companies used in their tests. Even though their paper is based on data we shared with them, CGSW declined to provide us with the requested list and stated that they would not do so prior to the publication of their paper in a journal (which might be many months away).

Claims Inconsistent with CGSW’s Own Results

CGSW claim that their matched sample analysis shows that “firms targeted by activist hedge funds improve less in value … than similarly poorly performing firms that are not subject to hedge fund activism.” However, the patterns displayed in the authors’ key Figure 1 do not support this central claim.

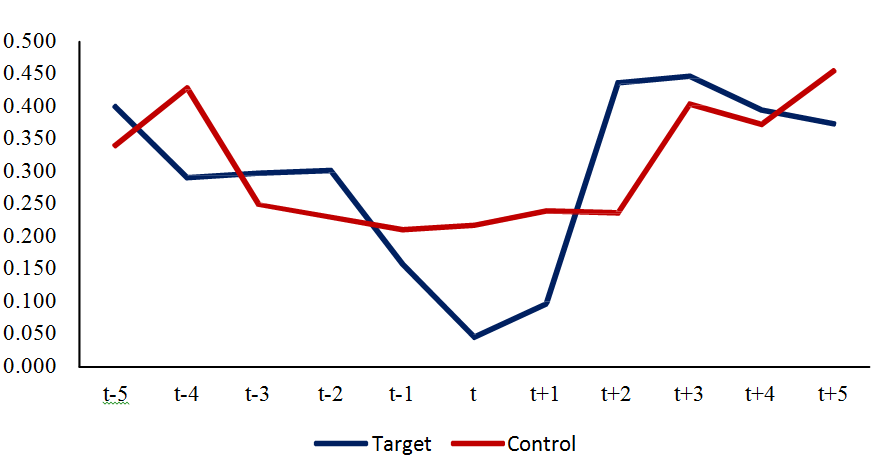

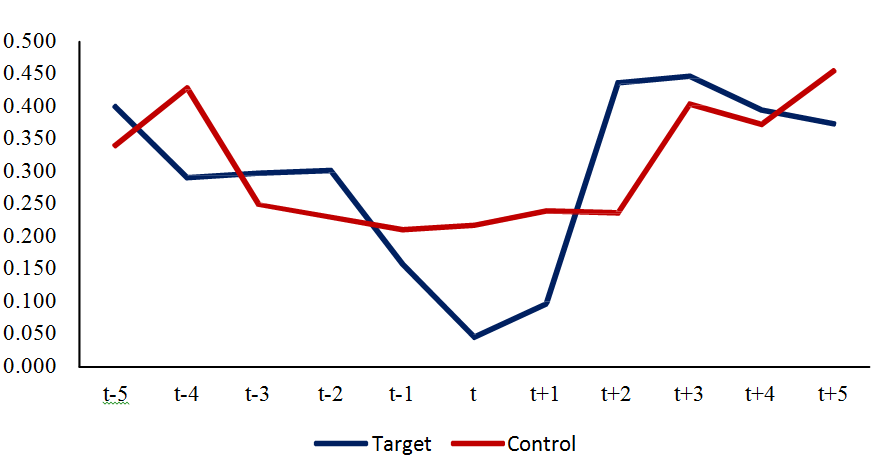

This Figure 1, which we reproduce below, reports industry-adjusted Tobin’s Q for firms targeted by hedge funds (blue graph) and industry-adjusted Tobin’s Q for the matched control firms (paired with the target firms by CGSW) during the years before and after the year at which target firms became a target.

Although the authors state that the Figure “confirms” their conclusions, it does not appear to do so. The Figure vividly shows that targets’ valuation increases more sharply than that of matched control firms that are not subject to hedge fund activism during the years following time t (denoting the end of the intervention year).

CGSW might argue that, although target valuation increases more sharply relative to matched control firms from time t (the end of the intervention year) forward, the activist intervention is responsible for the short-term decrease in value relative to control firms that targets experience from time t-1 (the beginning of the year of the intervention) to time t (the end of the year of the intervention). However, this short-term decrease is likely to at least partly precede the intervention and thus be a potential cause rather than a product of it. Furthermore, while opponents of hedge fund activism have been seeking to ground their opposition in claims regarding long-term effects, we are unaware of any claims by such opponents that such activism decreases value in the short term, and the well-documented stock market gains accompanying announcements of activist interventions would make such a claim implausible.

Indeed, CGSW themselves explain that the view that is empirically supported by their paper is that hedge fund interventions pressure management to produce short-term gains that come “at the potential expense of long-term performance.” This view implies a short-term increase in valuation followed by a decline in valuation during the years following the intervention year. The clear improvement in target valuation (relative to control firms) from time t forward displayed in Figure 1 thus contradicts CGSW’s claims and conclusions.

Tobin’s Q around the start of activist hedge fund campaigns (sample of all hedge funds campaigns)

Source: Cremers et al., November 2015, page 44.

Although the inconsistency of CGSW’s claims with their own Figure 1 is worth noting in assessing CGSW’s paper, we should stress that, due to the methodological problems noted below, we otherwise do not attach weight to the authors’ results, including those in Figure 1.

READ MORE »

Comment Letter of 18 Law Professors on the Trust Indenture Act

More from: Adam Levitin

Adam J. Levitin is Professor of Law at Georgetown University Law Center, specializing in bankruptcy, commercial law, and financial regulation. This post contains the text of a letter spearheaded by Prof. Levitin, and co-signed by 18 professors of bankruptcy and corporate finance law, regarding a proposed omnibus appropriations rider that would amend the Trust Indenture Act of 1939. The complete letter is available here.

We are legal scholars of corporate finance. We write because we are concerned by a proposed omnibus appropriations rider that would amend the Trust Indenture Act of 1939 without any legislative hearings or opportunity for public comment on the proposed amendment.

As you may know, the Trust Indenture Act is one of the pillars of American securities regulation. Congress passed the Trust Indenture Act in the wake of the Great Depression to protect bondholders in restructurings. Among other things, the Trust Indenture Act provides that no bondholder’s right to payment or to institute suit for nonpayment may be impaired or affected without that individual bondholder’s consent. These provisions are intended to protect bond investors by requiring any restructuring of bonds to occur subject to the transparency of a court supervised bankruptcy process, absent bondholder consent to a debt restructuring.

READ MORE »