Lane T. Ringlee is a Managing Partner at Pay Governance LLC. This post is based on a Pay Governance publication by Mr. Ringlee, Maggie Choi, Marizu Madu, and Peter Ringlee.

Companies have migrated a significant portion of equity compensation to performance-based long-term incentive (LTI) awards—typically performance shares or stock units (PSUs)—from stock options.[1] Over 80% of companies in the S&P 500 now have such plans; these also now comprise the majority weighting among LTI vehicles. This trend has been driven in, large part, by the desire of Compensation Committees to place at least one-half equity compensation in the form of “performance-based” pay as defined by the proxy advisory firms. With increasing pressure, committees have further focused these performance share plans to ensure clear and convincing alignment with total shareholder return (TSR), largely due to the pay for performance (P4P) evaluation methodologies employed by the proxy advisors and the diminution of stock options in the long-term incentive portfolio. In addition, the use of relative TSR as a PSU metric has provided another benefit to Compensation Committees: delivering a multi-year performance goal without the need for an annual target-setting exercise or justification of performance targets and ranges to the external world. We have referred to this trend relative TSR in PSU plan reliance in prior Pay Governance Viewpoints as a leading cause of the “homogenization” of pay programs.

Key Takeaways

- Performance share or unit (PSU) plans have largely used relative total shareholder return (TSR) or financial metrics partially due to many Committees’ preference for a “safe harbor” approach that proxy advisory firms will view favorably.

- Recent Pay Governance research indicates that just under 10% of large companies use strategic goals or objectives (SBOs) in their PSU plans.

- SBO use may help in motivating and rewarding executives for achieving critical strategic initiatives, organizational capabilities, or non-financial performance areas critical for future success. Moreover, SBOs can be particularly useful in setting the right goals during important transitional or turnaround situations.

- If SBOs are used, several important design considerations should be evaluated, including proxy advisor preferences and 162(m) deductibility.

The use of multi-year relative TSR and financial goals, as a large part of this transition, have come to dominate the performance scorecards for PSU plans and have resulted in a strict focus on “shareholder outcomes.” While these relative PSU plans provide the transparency and objectivity that appeal to the proxy advisory firms, they remain far from perfect. Common criticisms of plans that have exclusive or majority use of TSR and some financial measures include:

- Lack of impact: Management has little influence over stock price, especially measured against other companies’ performance, due to the impact of exogenous factors.

- Non-strategic: TSR and financial metrics measure outcomes rather than strategy. While these measures reflect quantity of performance, they do not necessarily reflect the underlying strategic initiatives that management must accomplish in order to drive improved enterprise value or the quality of management execution.

- Retrospective: Market and financial measures, in particular, will reflect value added or subtracted but won’t reflect the course that management must take to redirect or reorient the business model to drive shareholder value.

- Non-situational: An incentive scorecard needs to reflect the unique characteristics and life cycle of a company; TSR and many financial measures do not, although actual targets can be adjusted to reflect the financial situation. For a company engineering a strategic repositioning, creating a new venture through seed investments, or ensuring focus on critical non-financial capabilities, typical TSR or financial scorecards fall short of motivating and rewarding executives to achieve these critical milestones.

Pay Governance has often discussed the framework for executive compensation in our Viewpoints: executive rewards need to balance the tension between motivating and retaining top talent in a SOP world. This challenge reflects the conflict that companies face in developing scorecards for performance that balance the emphasis on achieving shareholder value-enhancing objectives with reflecting an environment that measures P4P using TSR over a defined measurement period.

Balancing the Focus: Shareholder Outcome and Strategy Execution

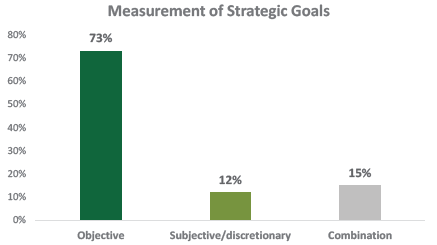

In our research of performance share plans, we have found that companies attempt to balance this tension between the “shareholder outcome” focus and the need to motivate and reward executives for “strategy execution.” One way companies have attempted to achieve this balance is through the combined use of financial and non-financial (or non-quantitative) goals in PSU plans. At this point, we view this as a potentially emerging practice that may represent a design applicable in specific instances. In our 2016 review of S&P 500 companies, we found that just under 10% of PSU plans include non-financial or non-quantitative goals that can be classified as “strategic business objectives” or “SBOs”; these objectives cover areas such as customer service, market share, safety, reliability, transformational initiatives, and strategic milestones. While the majority of companies set strategic goals that can be objectively measured, some continue to employ a subjective assessment of strategic achievements or performance.

Objective Subjective/discretionary Combination

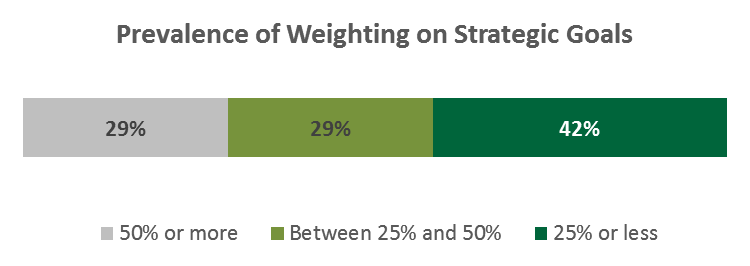

While significant percentage of the award opportunity is dependent upon achieving SBOs. More than 50% of companies place ≥25% weight on SBOs, with an average weighting of 35%.

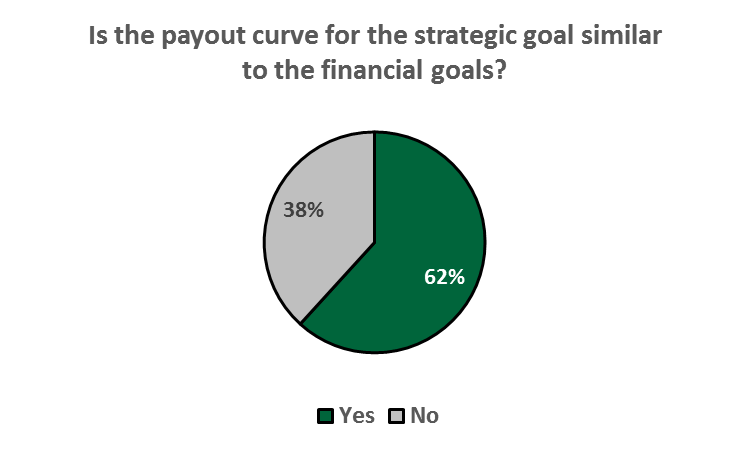

In terms of award calculation, SBOs are used much the same as financial metrics. The majority of companies (82%) add the weighted score of the strategic objectives to the weighted scores of other financial or market-based goals (an “additive” approach) instead of using a multiplicative or modifier approach. This additive method allows companies to segregate the performance assessment of SBOs and their impact on the overall award as opposed to blending SBO performance with all other results. In determining P4P leverage, the payout curve—threshold award and maximum award—for SBOs generally reflects the same structure as for the other financial or market-based measures on the scorecard. However, the performance levels for financial and non-financial goals are individually tailored to the measure.

As noted earlier, there are external influences on committees driving the adoption of 3-year measurement periods for PSU plans. In our research, we find that most companies with PSUs do have 3-year performance cycles (80%). For plans that include SBOs, a similar trend is observed: most companies have applied the 3-year period to all measures, including the SBOs (76%).

Why Include SBOs in PSUs?

We are not advocating this approach for all PSU plans; however, we believe there are situations where the inclusion of SBOs in an LTI plan can be particularly valuable and beneficial:

- Reward for key initiatives/milestones: In many instances, the use of SBOs reflects a company’s need to achieve crucial milestone goals or implement enhanced capabilities, such as technology-related improvements.

- Reflect leading performance indicators: Where companies have identified key performance drivers that will drive future financial performance and shareholder returns, such drivers should be communicated to management and included in incentive plans in the form of SBOs.

- Quality of performance: To complement TSR and financial performance goals, companies have used the SBO component to reflect the quality of organizational performance in key competency areas (eg, implementing the strategic plan, organizational culture, diversity, and others) that are not directly reflected in TSR or financial metrics.

Design Issues

IRC § 162(m) Deductibility

IRC § 162(m) limits the deduction for compensation above $1 million to qualified performance-based pay. Generally, this requires the compensation to be based on a formula or objective criteria. Companies can qualify compensation aligned to SBOs in PSU plans through several methods:

- Pre-Established Objective Goals: If the SBOs represent objective metrics included in the goals in the shareholder-approved stock plan, set in advance, and approved by the Compensation Committee, these will generally result in qualified compensation for purposes of deductibility. To be considered an objective goal, the SBO must meet the “third party test”: a third party must be able to reasonably determine if the SBO was met or not met after receiving all necessary facts.

- Threshold performance criteria: Requiring an objective, measurable threshold level of performance to be achieved before SBO performance is subjectively measured and used to determine a payout will allow for the deductibility of compensation in excess of the IRC § 162(m) limit. This “plan within a plan” approach is similar to the design used to qualify time-vested RSUs for deductibility: establish a threshold level of performance using a shareholder-approved goal in the stock plan. This structure allows the committee to apply discretion and subjective judgement in considering performance relative to the SBOs while still complying with IRC § 162(m).

As noted previously, 74% of companies in our 2016 review used pre-established objective goals to measure SBOs in their PSU plans, partially to qualify compensation for IRC § 162(m) deductibility. Companies should seek counsel from their legal, accounting, and tax advisors to identify the structure that best meets their compensation philosophy while complying with IRC § 162(m).

Proxy Advisor Views

A concern for companies making changes to incentive programs relates to the views of the proxy advisory firms and ISS in particular. The initial consideration for companies is to ensure that payouts from PSU plans do not conflict with the notion of P4P in the proxy advisor quantitative test. Additionally, from a qualitative review standpoint, effective goal disclosure is an important factor to avoid external criticism unless a company is able to limit disclosure under the exception provided for confidential information or information that could cause competitive harm. The use of strategic goals in PSU plans does not automatically trigger additional scrutiny or criticism from ISS.

A Case Study

A large energy company uses a combination of relative TSR, operational performance indicators, and progress toward implementing its strategic plan as its “inside plan.” The SBOs include organizational areas such as balance sheet strength, relationships with key stakeholders, and key organizational initiatives (ie, organizational culture, progress in diversity initiatives, adherence to governance principles, and organization reputation). The outside plan has multiple IRC § 162(m) thresholds for financial and TSR performance before the inside plan performance is assessed and awards are determined.

This case example illustrates the efficacy of including SBOs in a PSU plan:

- Focusing executives on long-term strategic decisions that will ultimately increase shareholder value

- Providing the committee flexibility, via the outside plan feature, to evaluate performance on the SBOs

- Including key areas reflecting the “quality” of performance and progress toward important company milestones and initiatives

Emerging Practice

In our research, we find that no more than 10% of large companies with PSUs currently include SBO goals and objectives. This is not surprising, given the unique circumstances or needs that may drive an organization to adopt these alternative performance areas, in addition to the preference of many committees to use a “safe harbor” approach that will receive favorable views from the proxy advisory firms.

Conclusion

The challenge of structuring a PSU performance scorecard that reflects the priorities of the organization persists for Compensation Committees. All too often, the exclusive use of relative TSR or financial metrics becomes the default selection without any consideration for the need to motivate and reward executives for achieving critical strategic initiatives, organizational capabilities, or non-financial performance areas crucial for future success. Consideration of SBO use in the performance scorecard for a PSU plan should be evaluated against these needs.

Endnotes:

1Pay Governance’s analysis of S&P 500 companies with the same incumbent CEO from 2009–2013 found the prevalence of PSUs to be 76% in 2013, an increase from 53% prevalence in 2009. (go back)

Print

Print