Ramey Layne, Brenda Lenahan, and Sarah Morgan are partners at Vinson & Elkins LLP. This post is based on a Vinson and Elkins publication by Mr. Layne, Ms. Lenahan, Ms. Morgan, Zach Swartz, K. Stancell Haigwood, and Layton Suchma.

Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (“SPACs”) continue to be increasingly popular vehicles for entities or individuals to raise capital to pursue merger opportunities, and for private companies seeking to raise capital, obtain liquidity for existing shareholders and become publicly traded.

This post provides an update to SPAC structures and transactions since a 2018 post (Special Purpose Acquisition Companies: An Introduction) and provides an expanded discussion of considerations for De-SPAC transactions and a description of recent SEC positions.

SPAC IPO Activity and Structure

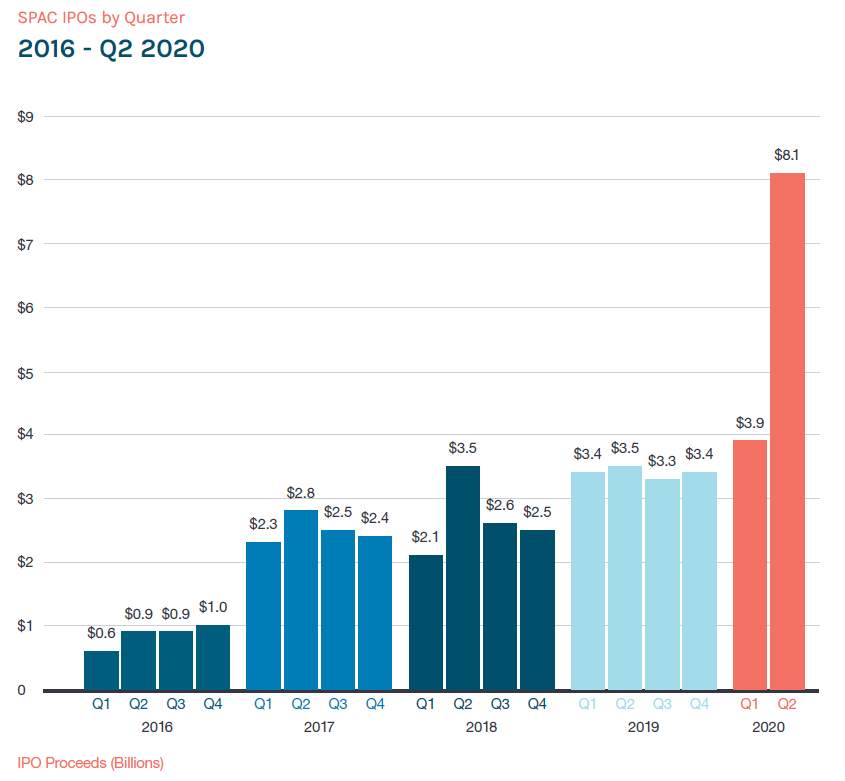

Since the beginning of 2016, each year has set a record in terms of total number of SPAC IPOs and the amount of capital raised in those IPOs. Through June 30, 2020, the year was on pace to exceed the prior year once again and, through the date of this article, the amount of capital raised in SPAC IPOs in 2020 has already eclipsed all of 2019. Since the beginning of 2020 through July 22, 2020, 48 SPAC IPOs have been completed, raising almost $18 billion in proceeds, with another $5.4 billion of SPACs on file to complete IPOs this year. SPACs have remained popular notwithstanding the COVID-related market disruption, perhaps because of the flexibility of SPACs to pivot to attractive industries based on changing market fundamentals, and in part because SPAC IPO investors have the downside protection of redemption decisions.

Source: VitalSigns IPO Data—Totals Exclude Overallotment Exercises

Since the 2018 post, SPAC IPOs continue to be typically structured as the issuance of a unit comprised of a share of stock and a warrant component. In some respects, the warrants have become more issuer friendly. For example, there are now examples of one-quarter warrants and one-fifth warrants—and one deal with no warrants at all—and several SPACs have included an option for the SPAC to redeem the warrants for stock. However, most SPACs now include an anti-dilution adjustment applicable to the warrants, commonly referred to as the “crescent term,” as described in the following paragraph.

In approximately a third of recent SPACs, the SPAC has the option to redeem the warrants for stock, with the amount of stock determined based on a grid of the period until expiration of the warrants and the fair market value of the common stock. The notice period required to exercise this feature is sufficiently long that warrant holders should have the ability to exercise it for cash if they would prefer.

The majority of SPACs since 2019 have included a “crescent term”—which is a provision to adjust the warrant strike price in the event of the issuance of additional securities below a specified threshold in connection with a business combination. Essentially, if a SPAC issues additional shares of common stock or other equity-linked securities for capital raising purposes (e.g., in a PIPE) in connection with its business combination and the price of those securities is below a specified threshold (generally, $9.20 or $9.50 per share), then the strike price for the warrants will be adjusted to 115% of the higher of (i) the market value or (ii) the price of the newly issued securities. Certain of the 2020 SPACs that include a crescent term also require that the gross proceeds of any such additional issuances exceed 60% of the IPO proceeds held in the SPAC trust account (plus interest and net of redemptions) in order for there to be an adjustment. Of the SPACs that went public in 2019 and the first half of 2020, a substantial majority included a crescent term.

Pershing Square Tontine Holdings: An Eleph-i-corn Hunter with Deviations from the Typical SPAC Structure

In July 2020, Pershing Square Tontine Holdings went public, as a SPAC focusing on “Mature Unicorns” that might need substantial liquidity or capital resources. It was the largest SPAC IPO ever, raising $4.0 billion, with another $1.0 billion under a committed forward purchase agreement and another $2.0 billion under options with the forward purchase subscribers. The SPAC has a number of notable aspects/ features, which distinguish it from typical SPACs:

- It is considerably larger than existing SPACs

- It does not have the typical founder share structure, equal to 20% of the post-IPO shares. Instead the sponsor and directors purchase warrants to buy roughly 6% of the shares of the company (calculated on a fully diluted basis as of the closing of the De-SPAC. The warrants are exercisable at $24.00 (20% above the IPO price) after 3 years

- The public warrants are a collective 1/3 warrant, but with a 1/9 warrant included in the unit having typical terms and a 2/9 warrant per IPO share having a “tontine” structure. To quote Monty Burns, “How many of you are familiar with the concept of a ‘tontine’?” Effectively, any 2/9 warrants of redeeming public shareholders are distributed among non-redeeming public shareholders, pro rata

- Underwriter compensation is considerably lower than typical, and there is no green shoe

- The Pershing Square Tontine SPAC was marketed as having competitive advantages over other SPACs due to its (1) larger amount of committed capital, (2) willingness to acquire a minority stake in a company, (3) ability to give a private company access to the public equity markets and (4) lower cost of capital compared to other blank check companies. The first (committed capital) and fourth (cost of capital) points have merit, while the second is less of a differentiator—most (62%) of the recent De-SPAC transactions referenced herein resulted in the SPAC shareholders (including PIPE investors) owning a minority interest in the resulting companies. The third point (access to public equity markets) is a feature of every SPAC, although there are examples where massive redemptions have resulted in the company effectively closing into a private transaction.

De-SPAC Considerations

SPACs and target companies considering De-SPAC transactions face an involved process. A De-SPAC transaction combines elements of a public company merger with considerations not generally applicable to transactions between operating companies and strategic or private equity buyers. These special considerations include: limited recourse to the SPAC’s IPO proceeds if the transaction does not close; the requirement for the SPAC to make redemption offers to its common shareholders; and the SPAC’s outside date. However, from the operating company’s point of view, merging with a SPAC may be an attractive alternative to an IPO due to market conditions, the amount of cash consideration offered relative to cash proceeds from an IPO, and speed of execution. From the SPAC’s point of view, a De-SPAC transaction is its raison d’être, so the complexities and considerations are what they are, but some De-SPAC transactions are simpler and more easily closed than others.

Each SPAC and operating company target will present unique considerations for the De-SPAC transaction. Not every SPAC is a suitable acquisition candidate for every operating company target and vice versa. Key issues for SPACs and operating companies participating in a De-SPAC transaction include obtaining the financial statements necessary for SEC filings, addressing the financing of the transaction, increasing transaction certainty, and evaluating and negotiating post-closing equity and governance structures. Due to the requirement of the shareholder vote and redemption offer, as well as the typical need for substantial third-party capital, both SPACs and target companies should be prepared for the potential renegotiation of the merger consideration or terms and ownership of the founder shares and warrants.

Between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2019, 47 De-SPAC transactions closed for SPACs that had IPO proceeds in excess of $100 million (an aggregate value of roughly $15.5 billion), with an aggregate consideration paid, excluding earn-outs and value of warrants, of approximately $38 billion. References below to “recent De-SPAC transactions” are to those 47 completed De-SPAC transactions.

SPAC Size and De-SPAC Transaction Value

While there is no maximum size of a target company, there is a minimum size (roughly 80% of the funds in the SPAC trust account), so a relatively small company would not be a suitable acquisition candidate for a relatively large SPAC unless combined with another sizable target. Occasionally, SPACs acquire multiple small targets simultaneously, where the individual targets are not sufficiently large to justify a bilateral transaction. SPACs typically seek to combine with target companies that have a value of two to four times the amount of their IPO proceeds in order to reduce the dilutive impact of the founder shares and warrants. Of the recent De-SPAC transactions, the average post De-SPAC equity capitalization (excluding earn-outs) has been approximately 2.9 times the size of the post-IPO SPAC capitalization.

Outside Date

As discussed elsewhere herein, each SPAC has an outside date by which time it is required (by its charter) to either consummate a De-SPAC transaction or liquidate. The outside date for each SPAC is different and is generally based on the SPAC’s IPO date. However, some SPACs include contingent extension provisions that can lengthen the SPAC’s life upon the occurrence of certain triggering events, which are most commonly the signing of a definitive purchase agreement or letter of intent or the contribution of additional funds into the trust account by the SPAC’s Sponsor.

Of the recent De-SPAC transactions, the average time from signing of the definitive agreements for the De-SPAC transaction to closing of the transaction has been approximately 4.5 months. Accordingly, a SPAC that has a short duration until its outside date needs to amend its charter (which must be accompanied by a redemption offer to its common stockholders) to extend its outside date to provide the necessary time to close the De-SPAC transaction.

Of the recent De-SPAC transactions, the duration from IPO closing to signing and announcement of the De-SPAC transaction has ranged from approximately 3.5 months to almost 35 months, with an average of approximately 15.5 months. Generally, the De-SPAC transactions that have the shortest duration from signing to closing are those where the proxy statement is filed shortly after signing the business combination agreement.

Approximately one-third of the recent De-SPAC transactions closed past the SPAC’s original outside date, requiring a shareholder vote to extend the date. One SPAC had a contingent extension feature permitting it to close the De-SPAC transaction past the original outside date without a charter amendment. Where an extension of the outside date is required, the extension vote is typically held within a few days of the original outside date and the SPAC must offer to redeem the public shares. Of the recent De-SPAC transactions completed after an extension and redemption offer, redemptions in connection with the extension averaged approximately 40%, and ranged from a de minimis number to 100% of the public shares.

Where a SPAC has a business combination announced at the time of the extension vote, the SPAC can often obtain an extension without providing any incremental value to shareholders. However, where the SPAC does not have a business combination announced, the SPAC will often provide for additional cash to be contributed to the trust account (for example $0.033 per non-redeemed share per month) to provide an economic incentive for shareholders not to redeem. These funds are most commonly provided by the SPAC’s Sponsor.

Capital Structure and Contractual Arrangements

The specifics of a SPAC’s post De-SPAC capital structure and contractual arrangements will be important to the SPAC’s Sponsor, management, financing sources (including the public shareholders) and, if the sellers will receive equity consideration in the SPAC, the target company shareholders. The dilutive effect of the founder shares, particularly as applicable to a backstop or PIPE investment, should be understood and may need to be modified.

In some recent transactions, the seller, PIPE investors, backstop investors, or debt financing sources received a portion of the founder shares or founder warrants. Where the dilutive effect of the founder shares is too large, the SPAC Sponsor can forfeit a portion of the founder shares or relinquish them subject to specified earn-in rights.

30 of the 47 recent De-SPAC transactions had founder shares forfeited, made subject to forfeiture or vesting, forfeited with conditional re-issuance, or transferred to PIPE or debt investors. Of the 30 transactions with forfeiture, vesting, etc., on average 37% of the founder shares were forfeited or made subject to vesting, etc.

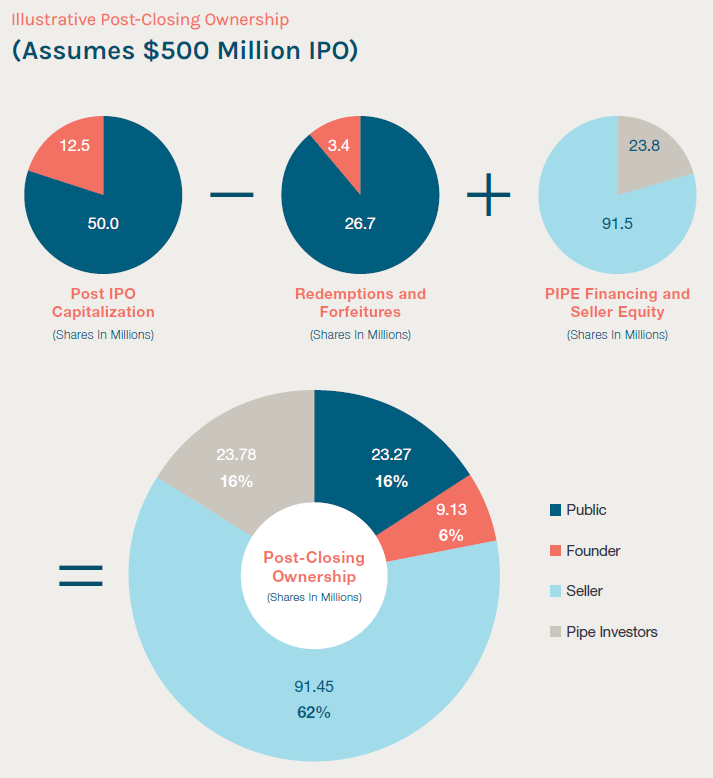

The above charts reflect an illustrative average of the adjustments in the 47 recent De-SPAC transactions, normalized to assume a hypothetical $500 million IPO. Post-IPO, the public owns 50 million shares in the SPAC and the founder owns 12.5 million shares, for the standard 80%/20% split. On average, the founder forfeited 3.6 million shares (27% of its 12.5 million) and the public redeemed 26.7 million shares (53% of their 50 million), inclusive of redemptions in connection with extension and redemption offers. On average, SPACs issued an incremental 23.8 million shares of common stock (or convertible preferred equity) in a PIPE to fund cash consideration and the seller received 91.5 million shares of common stock as stock consideration.

Available Capital

One of the most important considerations or constraints applicable to participants in the De-SPAC transaction is availability of capital. All of the SPAC’s IPO proceeds will generally be unavailable for the SPAC to pay deposits, break-up fees, expense reimbursements, etc., because the proceeds will be held in the SPAC’s trust account. In certain circumstances, the SPAC may have a small amount of cash on hand after its IPO or interest income it can withdraw from the trust account, but this amount will often be insufficient for the SPAC to pay its own expenses, let alone the expenses of the target company or a deposit, commitment fee or break-up fee. A key differentiator among SPACs is whether the SPAC has an affiliate or third party willing to commit to backstop redemptions and purchase additional equity to the extent necessary to fund the cash purchase price for the De-SPAC transaction. These parties may also be willing to enter into alternative purchase agreements with the target company, commit to purchase SPAC common stock on the market (and agree not to redeem such shares), fund transaction fees and expenses, and provide capital for termination fees if the De-SPAC transaction does not receive the necessary approvals or is otherwise not consummated.

Of the 47 recent De-SPAC transactions, 38 were funded with common equity only PIPEs, six had common and preferred equity PIPEs, and one had a preferred equity only PIPE. The amount of cash raised in these 38 transactions ranged from roughly 3% of the IPO size to 358% of the IPO size.

Financial Statements Required

The 2018 post stated that the proxy and tender offer rules provide that the audited financial statements of the target business in the proxy statement or tender offer materials may be audited under the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (“AICPA”) rules. However, the staff of the SEC has issued informal guidance and comment letters indicating that the SEC’s position is that the proxy statements and tender offer materials should contain financial statements audited under the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (“PCAOB”) rules, notwithstanding that the proxy and tender rules permit AICPA audits. The practice of the SEC appears to be to review initial submissions (i.e., the staff

is not issuing bedbug letters, also known as “Series Filing Deficiencies” letters), and perhaps one amendment, of proxy or tender offer materials with AICPA-compliant audited financial statements, but thereafter to insist on PCAOB-compliant audited financial statements before reviewing proxy or tender offer materials further. However, practical considerations may mitigate to deferring filing until the PCAOB-audited financial statements are available prior to filing the preliminary materials.

Of the 47 Recent De-SPAC Transactions Surveyed:

- Total redemptions (including at extension vote) ranged from no redemptions to 100% redeemed, with an average of 53%

- While the transactions ranged from all cash consideration to all equity consideration, on average, consideration paid to the owners of the target averaged 71% equity/29% cash

- 83% had PIPE Cash raised ranged from roughly 3% of the IPO size to 358% of the IPO size, with an average of 56%

- Two thirds of transactions had founder shares forfeited, subjected to forfeiture, or transferred to PIPE or debt investors. On average, roughly one third of the founder shares were forfeited, conditioned or transferred

- Almost half raised debt in connection with the transaction

Resulting Form and Domicile

All SPACs to date have been structured as corporations, whether domiciled in Delaware, the Cayman Islands, or another jurisdiction, and all SPACs have been subject to U.S. federal income tax. The choice of post-IPO jurisdiction is driven by a strategic decision of where the ultimate target business may reside, balanced with certain tax considerations. As a general rule, U.S.-domiciled SPACs will face inversion issues in transitioning to a foreign domicile in the De-SPAC transaction, and all SPACs will be practically prohibited from converting from corporate to pass-through taxation. Accordingly, the entity resulting from a De-SPAC transaction will:

- likely be a corporation for S. federal income tax purposes;

- likely be a U.S. domestic entity if it were a Delaware SPAC, although there are exceptions to this general rule—of the recent De-SPAC transactions, 30 were Delaware SPACs and five of these redomesticated to the Cayman Islands, the Bahamas, Jersey (the Channel Islands), The Netherlands or Luxembourg; and

- be able to domesticate into the United States or most other jurisdictions if it were a non-U.S. SPAC—of the recent De-SPAC transactions, 17 were non-U.S. SPACs and 11 redomesticated to Delaware, Maryland or New York.

Despite being a corporation for U.S. federal income tax purposes, the resulting entity could use the Up-C structure to permit pass-through tax treatment for the owners of the target business and other participants.

SPAC Regulatory Treatment and Transition from Shell Company Status

SPACs, as registrants with assets consisting solely of cash and cash equivalents, are “shell companies” under the Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the “Securities Act”), and forms and regulations thereunder. [1] SEC regulations prohibit or limit the use by shell companies (SPACs) and former shell companies (former SPACs) of a number of exemptions, safe harbors and forms that are available for other registrants. Some of these restrictions were adopted by the SEC in 2005 in response to the perceived use of certain shell companies as vehicles to commit fraud and abuse the SEC’s regulatory processes. The restrictions apply to SPACs and former SPACs for varying periods, depending on the specific rule.

For example, a former SPAC is not eligible to register offerings of securities pursuant to employee benefit plans on Form S-8 until at least 60 days after it has filed a “Super 8-K,” which is a special 8-K that SPACs must file following the completion of their business combination. In addition, stockholders of former SPACs are required to hold their equity for a period of 12 months, measured from the date of the filing of the Super 8-K, before they can rely on Rule 144 under the Securities Act. Rule 144 provides a means by which persons who might otherwise be considered “statutory underwriters” (and therefore required to register their offer of equity under the Securities Act prior to their public sale) may sell their equity without registration, typically after a six-month holding period.

Further, SPACs and former SPACs (i) are not eligible to be well-known seasoned issuers or to use Free Writing Prospectuses (other than those limited to a description of the offering or the securities) until at least three years after the De-SPAC transaction and (ii) are limited in their ability to incorporate by reference information into long-form registration statements on Form S-1. [2] SPACs always qualify as “emerging growth companies” at IPO, entitling them to conduct “testing the waters” meetings with institutional investors at any time. But, as “shell companies” under SEC rules, SPACs are unable to use graphic materials in roadshows or use recorded roadshows due to restrictions on using Free Writing Prospectuses described previously.

In addition to special treatment under SEC regulations, the SEC has also adopted several positions applicable to former SPACs, including a position that former SPACs are not eligible to use Form S-3 until 12 full calendar months from the filing of the Super 8-K.

Conclusion

Since the 2018 post, pace of SPAC IPOs and De-SPAC transactions has continued to grow. SPACs have gotten larger, aggregate amount of capital hunting has increased, and more and more well-known names have endorsed the SPAC structure (either as founder or as merger counterparty). SPACs appear to now be a mainstream alternative to an IPO.

Endnotes

1SPACs are similar to “blank check companies,” which the SEC describes as “a development stage company that has no specific business plan or purpose or has indicated that its business plan is to engage in a merger or acquisition with an unidentified company or companies, or other entity or person[.]” The SEC sometimes describes SPACs as “blank check companies.” However, blank check companies are defined as development stage companies that have indicated that their business plan is to engage in a merger or acquisition with an unidentified company or companies and that are issuing “penny stock” under Rule 3a-51 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Blank check companies are subject to Rule 419 of the Securities Act. SPACs are not blank check companies within the scope of Rule 419 because SPACs have charter restrictions prohibiting them from being “penny stock” issuers (the term “penny stock” generally refers to a security issued by a very small company that trades at less than $5 per share). The major differences between SPACs and blank check companies/penny stock issuers are that SPAC equity may trade on an exchange prior to the SPAC’s business combination, brokers are not subject to heightened requirements on trades in SPAC securities, SPACs have a longer time period to complete their business combinations and SPACs are not prohibited under SEC rules from using interest earned on the trust account prior to the business combination.(go back)

2In addition, as a technical matter, former SPACs may not use the “Baby Shelf Rule” (which permits registrants with a public float of less than $75 million to use short-form registration statements on Form S-3 for primary offerings of their shares) for twelve months after the Super 8-K filing. However, the SEC Staff’s position that former SPACs are not eligible to use Form S-3 until 12 full calendar months from the filing of the Super 8-K renders this technicality moot, suggesting that the SEC should change their policy to match the form, or change the form to match their policy.(go back)

Print

Print

One Comment

Great article!

Which is the smallest spac ipo ever created?

Is it possible to create a small spac ipo in the otcmarkets??? If is, which are the smallest amount that a spac ipo can raise in order to fund a small business? Many thanks in advance