Joni S. Jacobson, David H. Kistenbroker, and Angela M. Liu are partners at Dechert LLP. This post is based on a Dechert memorandum by Ms. Jacobsen, Mr. Kistenbroker, Ms. Liu, Christopher J. Merken, Andrew Stahl, and Austen Boer.

Introduction

In 2022, plaintiffs filed 34 securities class action lawsuits against non-U.S. issuers. [1]

- As was the case in 2021 and 2020, the Second Circuit continues to be the jurisdiction of choice for plaintiffs bringing securities claims against non-U.S. issuers. Roughly 80 percent of these 34 lawsuits (28) were filed in courts in the Second Circuit. A majority (20) of these lawsuits were filed in the Southern District of New York, followed by the Eastern District of New York (8). The Third (3), Ninth (2), and Fourth (1) Circuits followed.

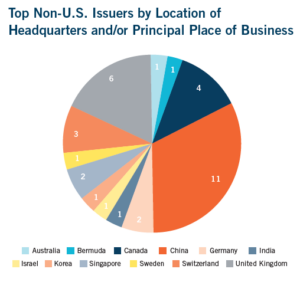

- Continuing the trends in 2021 and 2020, most non-U.S. issuer lawsuits were against companies with headquarters and/or principal places of business in China. Of the 34 non-U.S. issuer lawsuits filed in 2022, 11 were against non-U.S. issuers with headquarters and/or principal places of business in China, followed by the United Kingdom (6), Canada (4), and Switzerland (3).

- Pomerantz LLP led with the most first-in-court filings against non-U.S. issuers in 2022 (10), followed by The Rosen Law Firm, P.A. (8), and Robbins Geller Rudman & Dowd LLP (7). Although Pomerantz and The Rosen Law Firm jockey for the most active plaintiff’s law firm, in 2022 Pomerantz took the top spot that The Rosen Law Firm had occupied from 2018 through 2021. Also, like the trend of the last several years, The Rosen Law Firm was appointed lead counsel in the most cases in 2022 (with 6), followed closely by Pomerantz and Levi & Korsinsky, LLP (with 4 each) and Robbins Geller (with 3).

- A slim majority of securities class actions against non-U.S. issuers (18 of 34) were filed in the first and second quarters of 2022, a departure from 2021, where the majority of lawsuits were filed in the third and fourth quarters.

- Although the suits cover a diverse range of industries, the largest portion of the suits involved the education and schooling industry (5), the retail industry (4), and the software and programming, money center banks, and biotechnology and drug industries (3 each).

An examination of the types of cases filed in 2022 reveals the following substantive trends:

- Five cases were filed against online Chinese tutoring companies alleging misrepresentations in connection with China’s regulatory requirements and/or approvals.

- Compared to the prior three years, 2022 saw relatively no change in the number of dispositive decisions issued in securities fraud cases against non-U.S. issuers. In 2022, courts rendered eight dispositive decisions in favor of defendants in cases filed in 2020 and 2021.

- Although it is hard to discern trends from eight dispositive decisions, the courts’ reasoning underlying the dismissal orders is still instructive for non-U.S. issuers that find themselves defending a securities class action. In the dismissal orders issued in 2022, most courts held that plaintiffs failed to allege an actionable misstatement or omission, while several courts also held that plaintiffs had failed to allege a strong inference of scienter.

Non-U.S. Companies Remain Popular Targets for Securities Fraud Litigation

In recent years, non-U.S. issuers have become targets of securities fraud lawsuits, a trend that continued in 2022. In 2022, there was a small decrease in securities class actions filed against non-U.S. issuers but this was against the backdrop of a decrease in the overall number of securities class actions filed in 2022. This survey is intended to give an overview of securities lawsuits against non-U.S. issuers in 2022. First, we analyze the number of cases filed, including trends relating to location filed, types of companies that were targeted, and the nature of the underlying claims. Next, we analyze certain dispositive decisions rendered in 2022 and how they may impact the legal landscape of these types of suits. Finally, we set forth best practices non-U.S. issuers should consider implementing to reduce the risk of such lawsuits.

The Second Circuit, and particularly the Southern District of New York (“SDNY”), continued to see the most activity in 2022. With 20 filings in SDNY, it was the preferred court for about 59 percent of all lawsuits brought against non-U.S. issuers in 2022 (up from about 48 percent in 2021). After the Second Circuit, the Third (3), Ninth (2), and Fourth (1) Circuits followed in number of suits filed.

Filing Trends

In 2022, there was a decrease in the total number of federal securities class actions, with 197 cases filed. Interestingly, as compared to the total number of federal securities class actions filed in 2022, the percentage of cases filed against non-U.S. issuers also decreased significantly from the previous year, with just over 17 percent of lawsuits (34) filed against non-U.S. issuers, compared to 2021 in which 20 percent of the class actions were filed against non-U.S. issuers. As in years past, certain filing trends emerged:

- The majority of suits were filed against companies headquartered in China (11), the United Kingdom (6) and Canada (4).

- The SDNY was the most popular venue for suits against companies headquartered in China, with 10 of 11 cases filed in the SDNY, followed by 1 filed in the Eastern District of New York (“EDNY”). [2]

- Of the 6 suits filed against United Kingdom-based companies, 3 were filed in SDNY, 2 were filed in the EDNY, and 1 was filed in the District of New Jersey. [3]

- Of the 4 suits filed against Canada-based companies, 3 were filed in the EDNY and 1 was filed in the District of Maryland. [4]

- Although the suits cover a diverse range of industries, the largest portion of the suits involved (i) the

education and schooling industry (5) – all of which were against companies headquartered in China; and (ii) the retail industry (4) – three of which were against companies headquartered in China.

Substantive Trends

Misrepresentations and/or Omissions Relating to Government Regulations and Their Effect on Private Chinese Tutoring Companies

An emerging trend in 2022 involved Chinese companies’ alleged failure to disclose that the Chinese government had adopted stringent new regulations for the online education market. After one lawsuit was filed in 2021 alleged the defendants failed to disclose these new regulations prior to the company’s Initial Public Offering (“IPO”), [5] this trend grew in 2022. Five of the 11 lawsuits filed against Chinese companies related to newly adopted regulations for after-school tutoring companies.

As one complaint explains, “for-profit tutoring in China emerged in the 1980s and 90s as the country began its shift toward market economies,” particularly after the Chinese government reinstated the Gaokao—China’s national college entrance exam—in 1977. [6] By 2004, “almost three-quarters of primary school students in China had received tutoring lessons in both academic and non-academic subjects.” [7] Another complaint alleged that “Chinese parents were willing to spend significant sums of money – tens of thousands of dollars each year – for after-school tutoring services. In fact, estimates indicate that some Chinese parents spent between 25 percent and nearly 50 percent of their annual income on after-school tutoring.” [8]

In 2018, the Chinese government began restricting the private tutoring industry. In February 2018, the Ministry of Education issued the “Circular on Alleviating After-school Burdens on Primary and Secondary School Students and Implementing Inspections on After-school Training Institutions,” and in August 2018, the Chinese State Council issued Circular 80 “which limited curriculum content, imposed additional certification requirements for after-school tutoring institutions, banned homework,

imposed early class stopping times and forbade tutoring companies from collecting more than three months’ worth of fees.” [9] Eventually, in July 2021, Chinese authorities issued new regulations banning after-school tutoring companies that teach the school curriculum from making profits, raising capital, or going public. [10]

Several of the non-U.S. issuer complaints relate to material misstatements and/or omissions Chinese tutoring companies made in their Registration Statements and related prospectuses ahead of their IPOs. For example, in Zhang v. 17 Education & Technology Group Inc., [11] the tutoring company held its IPO on December 4, 2020. [12] Plaintiffs allege that “[t]hroughout the Registration Statement, 17EdTech neglected to raise the real and existential concerns about the ongoing discussions and actions of Chinese authorities related to 17EdTech’s K-12 education services . . . .” [13] Principally, plaintiffs contend that statements in 17EdTech’s Registration Statement were false and/or misleading and/or failed to disclose that: (1) 17EdTech’s K-12 Academic Services would end less than a year after its IPO; (2) as part of its ongoing regulatory efforts, Chinese authorities would imminently curtail and/or end 17EdTech’s core business; and (3) as a result, the defendants’ statements about the company’s business, operations, and prospects were materially false and misleading and/or lacked a reasonable basis. [14] “Since the IPO, and as a result of the disclosure of material adverse facts omitted from the company’s Registration Statement, 17EdTech’s ADS price has fallen significantly below its IPO price,” with an alleged decline of 85 percent from the IPO price. [15]

Plaintiffs do not allege that the 17EdTech defendants had any specific knowledge of the impending changes in China’s tutoring regulatory scheme. Instead, Plaintiffs’ allegations focus broadly on China’s “long-standing plan to reform the after-school tutoring industry,” including speeches made by Chinese President Xi Jinping, meetings of China’s State Council, and publications addressing coming reforms. [16] But the Amended Complaint contains no allegations regarding any defendant’s specific knowledge of these speeches, meetings, or publications.

For its part, 17EdTech’s IPO Registration Statement included the following warning about the Chinese

regulatory risk factor:

Uncertainties exist in relation to new legislation or proposed changes in the PRC regulatory requirements regarding online private education and smart in-school classroom solutions, which may materially and adversely affect our business, financial condition and results of operations. [17]

The Registration Statement also disclosed that its 17EdTech’s services were subject to Chinese regulations and included “a lengthy summary of existing regulations formally promulgated by PRC authorities” including many of those discussed in plaintiffs’ broader factual allegations. [18]

Other non-U.S. issuer complaints focus on material misstatements and/or omissions relating to the

potential impact of the anticipated regulations on the company’s business. For example, in Zhang v. Gaotu Techedu Inc., [19] Plaintiffs allege that Gaotu made material misrepresentations and/or omissions between March 5, 2021 and July 32, 2021. [20] On March 4, 2021, the company held its Q4 2020 Earnings Call, during which Gaotu’s CEO stated he anticipated revenue growth in the range of 70 percent to 80 percent. [21] When asked about the Chinese government’s regulation of after-school tutoring programs, the company’s CFO explained the company was “operations-oriented” and not “trafficoriented.” [22] Plaintiffs allege these statements were materially false and misleading and that the defendants made false and/or misleading statements and/or failed to disclose, among other things: (1) that China was barring tutoring for profit in core school subjects and the policy changes would restrict foreign investment in a sector that had become essential to success in Chinese school exams; and (2) the impact those regulations would have on Gaotu’s operations and profitability. [23]

These complaints based on the Chinese government’s regulations of after-school tutoring continue the 2021 trend of lawsuits filed against non-U.S. issuers related to regulatory requirements.

Cases Against Other Non-U.S. Issuers Involved a Wide Variety of Misrepresentations and/or Omissions

Cases against other non-U.S. issuers included a wide variety of claims against businesses in a wide variety of industries.

Several pharmaceutical companies faced suits based on their alleged overstatement of their drugs’ commercial prospects. In Fernandes v. Centessa Pharmaceuticals, [24] PLC, plaintiffs sued Centessa, a clinical-stage pharmaceutical company, because it allegedly failed to disclose its drugs were less safe than it had represented and it overstated the drugs’ clinical and commercial prospects. [25] Centessa is based in England. [26] Similarly, in Ortmann v. Aurinia Pharmaceuticals Inc., [27] plaintiffs sued Aurinia, a biopharmaceutical company, claiming it allegedly failed to disclose its only product was suffering declining sales and it overstated the drug’s commercial prospects. [28] Aurinia is based in Canada. [29]

Other companies were sued over alleged bribes or anticompetitive or corrupt practices. In In re

Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson Securities Litigation, [30] for example, Plaintiffs sued Ericsson, a multinational telecommunications company, alleging that it “made a series of misrepresentations concerning growth in Iraq and the legality and compliance of its operations in Iraq . . . when in truth, Ericsson was carrying out an elaborate scheme to grow its business by making bribes and protection payments to corrupt officials and terrorist organizations in Iraq.” [31] Ericsson is based in Sweden. [32] And in Choi v. Coupang, Inc., [33] plaintiffs sued Coupang, an e-commerce business “commonly referred to as the Amazon.com of South Korea” alleging that it was engaged in anti-competitive practices with its suppliers and other third parties and that its “lower prices, historical revenues, competitive advantages, and growing market share were the result of systematic, improper, unethical, and/or illegal practices.” [34] Coupang is based in South Korea. [35]

Motion to Dismiss Decisions

In 2022, for cases filed in 2020 and 2021, there were eight dispositive motions to dismiss granted with

judgments entered, one motion denied, and six motions granted in part. [36] Of the eight decisions in 2022, five of the securities class actions were filed in the S.D.N.Y. [37] Although it is challenging to discern trends from only eight dispositive decisions, the courts’ reasoning

for dismissing these cases is still instructive for non-U.S. issuers who find themselves the subject of class actions lawsuits. In 2022, the primary reason courts dismissed complaints was for failures to allege any actionable or material misstatement, though certain courts also found that plaintiffs failed to allege a strong inference of scienter.

Failure to Allege an Actionable or Material Misstatement or Omission

In 2022, courts dismissed claims that failed to allege actionable or material misstatements or omissions relating to, among other things, risks relating to COVID-19, financial and performance forecasts, and regulatory risk factors.

A common theme was dismissal for attempting to plead “fraud by hindsight,” i.e., alleging a defendant’s statement was false based on subsequently available information without also alleging the defendant knew the statement was false when it was made. In Benedetto v. Qudian Inc., [38] plaintiffs challenged several of the defendants’ statements, alleging that defendants made a number of false and misleading statements and omissions, including by misrepresenting that Qudian’s business was compliant with China’s new regulations focused on the online consumer lending industry, and by misrepresenting that Qudian was experiencing significant growth while remaining conservative in its lending practices. [39] Qudian had issued several optimistic updates to its 2019 financial guidance but then experienced poor performance, causing it to abandon its financial guidance and eventually report revenue far below that originally projected. [40] In dismissing the complaint, the S.D.N.Y. found that the plaintiffs engaged in “a clear attempt to plead fraud by hindsight.” [41] Although the court found a minority of the challenged statements to be materially false or misleading—specifically, statements that Qudian was fully compliant with all regulations and that Qudian’s funding partners performed required credit assessments—it also found that the plaintiffs failed to adequately plead scienter. [42] Allegations regarding potential misconduct by Qudian’s funding partners, standing alone, were insufficient to establish that the defendants lacked a basis to believe in their guidance statements or were aware of that alleged misconduct. [43] Similarly insufficient were broad allegations that the individual defendants held board positions and were therefore privy to information that was misrepresented or omitted. [44] Further, the court found insufficient plaintiffs’ allegations regarding potential motives of executive compensation or a desire to appear successful following past business failures. [45]

In another case concerning defendants’ optimistic opinions, Cachia v. BELLUS Health Inc., [46] the plaintiff alleged that BELLUS Health misled investors as to the “design, enrollment, and ability to demonstrate the efficacy of” the company’s one potential product, a drug for treating chronic coughing. [47] In response, the defendants argued “that they had truthfully disclosed the specifics of the trial and believed in the strength of the trial’s design.” [48] The court agreed with the defendants and ruled that “Plaintiff’s securities fraud theories fail because he does not identify a single false statement or omission that makes any statement misleading.” [49] Similar analysis controlled in Alperstein v. Sona Nanotech Inc., [50] another suit concerning a failed attempt to develop medical technology.

Other dispositive decisions continued to implicate “fraud by hindsight,” particularly where irregularities in financial data were concerned. In In re GOL Linhas Aereas Inteligentes S.A. Securities Litigation, [51] the plaintiffs alleged that defendants made misleading statements in a May 2020 earnings report in which defendants “touted” the company’s “effective and structured liquidity management.” [52] Plaintiffs’ justification for this allegation was that the defendants’ external auditor released a report the following month stating that it had “substantial doubt about GOL’s ability to continue as a going concern and had identified material weaknesses in GOL’s internal controls over financial reporting.” [53] The court dismissed the complaint, finding that plaintiffs had failed to adequately plead that defendants knew about the audit report at the time of the statements or that they acted with scienter. [54]

In another case, Yaroni v. Pintec Technology Holdings Limited, [55] plaintiffs alleged that defendants made material misstatements or omissions in defendants’ offering materials concerning internal controls, cash loans made to purportedly related parties, revenue recognition practices, and certain line items in the company’s financial statements. However, the court found that the claims were not actionable because the defendant had precisely warned of exactly those risks. [56] And, to the extent that plaintiffs alleged that defendants warned of risks that had already materialized, they failed to allege that defendants knew, or should have known, about those issues at the time of the company’s IPO. [57]

In 2022, two dispositive decisions arose, in part, from purported nondisclosures of the risks posed by COVID-19 during the early stages of the pandemic. In both cases, the court found that plaintiffs failed to plausibly plead that defendants had actual knowledge that COVID-19 would have material impacts on their businesses. In Gutman v. Lizhi Inc., [58] plaintiffs asserted securities violations arising from defendants’ January 17, 2020 IPO and related Registration Statement. Although the Registration Statement warned that “health epidemics” may negatively impact the company, plaintiffs alleged that COVID-19 was “already ravaging China” and “negatively affecting Lizhi’s business. [59] Plaintiffs alleged that, because Lizhi was a Chinese business with at least some operations in Wuhan, it was “uniquely situated to recognize the then-existing impact was having on their business and operations, and the serious, foreseeable threat the coronavirus continued to pose to their future financial condition and operations.” [60] The court disagreed and dismissed the complaint, finding that plaintiffs had failed to allege an actionable omission because “COVID-19 was not a known trend at the time of the January 17, 2020 IPO.” [61]

The court further found that the “allegations at most suggest that defendants knew COVID-19 existed, not that it would persist and spread globally.” [62]

In a similar case, Wandel v. Phoenix Tree Holdings Limited, [63] the S.D.N.Y. dismissed a complaint alleging, in part, that the defendants omitted information on the risks of COVID-19 in their January 17, 2020 IPO documents. The court dismissed these allegations under nearidentical reasoning to that in Lizhi, finding that “the risk of COVID-19 was neither known nor knowable to Phoenix Tree by the start of the IPO.” [64] Plaintiffs further alleged wrongdoing unrelated to COVID-19, namely that defendants misleadingly withheld information on renter complaints and company finances for the fiscal quarter immediately preceding the company’s IPO. [65] The court dismissed these allegations. The court found that the company’s filings “discussed renter satisfaction (and the risks of dissatisfaction) multiple times,” thereby adequately warning reasonable investors. [66] Further, because the IPO occurred shortly after the end of the previous quarter and defendants “clearly warned investors that Phoenix Tree still needed time to assess its financial results. . . and that any data it did report were merely preliminary,” there was no actionable misstatement. [67]

Finally, in In re 360 DigiTech, Inc. Securities Litigation, [68] plaintiffs a series of misrepresentations concerning defendants’ compliance with Chinese regulations governing the collection of user data. In a brief opinion, the court dismissed the complaint as the plaintiff failed to allege that defendants’ practices violated Chinese law during the relevant period, did not name which laws were allegedly violated, or what specific acts or practices violated those laws. [69] The court also found that the plaintiff failed to adequately plead scienter. [70]

Conclusion

Though the overall number of securities class actions has gone down in 2022, the proportion of cases against non-U.S. issuers has not changed significantly. A company does not need to be based in the United States to face potential securities class action liability in U.S. federal courts. As such, it is imperative that non-U.S. issuers take steps to mitigate their risks in not only their home jurisdictions but also in the United States.

non-U.S. issuers should be particularly cognizant when

making disclosures or statements to:

- speak truthfully and to disclose both positive and negative results;

- ensure that a disclosure regimen and processes are well-documented and consistently followed;

- work with counsel to ensure that a disclosure plan is adopted that covers disclosures made in press releases, SEC filings and by executives; and

- understand that companies are not immune to issues that may cut across all industries.

non-U.S. issuers should work with the company’s insurers and hire experienced counsel who specialize in and defend securities class action litigation on a full-time basis.

Finally, to the extent that a non-U.S. issuer finds itself the subject of a securities class action lawsuit, the bases upon which courts have dismissed similar complaints in the past can be instructive.

Endnotes

1Unless otherwise noted, the figures in this white paper are based on information reported by the Securities Class Action Clearinghouse in collaboration with Cornerstone Research, Stanford Univ., Securities Class Action Clearinghouse: Filings Database, Securities Class Action Clearinghouse (last visited January 6, 2023), http://securities.stanford.edu/filings.html. A company is considered a “non-U.S. issuer” if the company is headquartered and/or has a principal place of business outside of the United States. To the extent a company is listed as having both a non-U.S. headquarters/ principal place of business and a U.S. headquarters/principal place of business, that filing was also included as a non-U.S. issuer.(go back)

2Two lawsuits were originally filed in the Central District of California, and one lawsuit was originally filed in the EDNY. All three were transferred to the SDNY upon the parties’ consent.(go back)

3One lawsuit was originally filed in the Central District of California but was transferred to the SDNY upon the parties’ consent.(go back)

4One lawsuit was originally filed in the EDNY but was transferred to the District of Maryland upon the parties’ consent.(go back)

5See Banerjee v. Zhangmen Educ. Inc., 21-cv-09634 (S.D.N.Y.). On June 10, 2022, defendants moved to dismiss the plaintiffs’ operative complaint. See ECF No. 40. The motion was fully briefed on September 9, 2022 and is pending before the court.(go back)

2In re New Oriental Educ. & Tech. Grp. Inc. Sec. Litig., 22-cv-1014 (S.D.N.Y.), ECF No. 63, ¶ 47 (Plaintiffs’ Second Amended Complaint).(go back)

7Id. 48(go back)

8N.M. State Inv. Council v. Tal Educ. Grp., 22-cv-1015 (S.D.N.Y.), ECF No. 46, ¶ 4 (Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint).(go back)

9Id. 6.(go back)

10Zhang v. 17 Educ. & Tech. Grp. Inc., 22-cv-9843 (S.D.N.Y.), ECF No. 37 (Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint), ¶ 11; see also Alexandra Stevenson & Cao Li, China Targets Costly Tutoring Classes. Parents Want to Save Them., N.Y. Times (Oct. 21, 2021), bit.ly/402ldwi (discussing China’s ban on “private companies that offer after-school tutoring and targeting [of] China’s $100 billion for-profit test-prep industry.”).(go back)

1122-cv-9843 (C.D. Cal.).(go back)

12Id. at ECF No. 1, ¶ 2.(go back)

13Id. ¶ 44.(go back)

14Id. ¶ 47.(go back)

15Id. ¶ 55.(go back)

16See id. ¶¶ 42–62.(go back)

17Id. ¶ 108.(go back)

18Id. ¶ 72.(go back)

1922-cv-7966 (E.D.N.Y.).(go back)

20Id. at ECF No. 1, ¶ 1.(go back)

21Id. ¶ 15.(go back)

22Id. ¶ 16.(go back)

23Id. ¶ 19.(go back)

2422-cv-8805 (S.D.N.Y.).(go back)

25Id. at ECF No. 1, ¶ 6.(go back)

26Id. ¶ 20.(go back)

2722-cv-1335 (D. Md.).(go back)

28Id. at ECF No. 1, ¶ 3.(go back)

29Id. ¶ 12.(go back)

3022-cv-1167 (E.D.N.Y.).(go back)

31Id. at ECF No. 39 (Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint), ¶ 192.(go back)

32Id. ¶ 62.(go back)

3322-cv-7309 (S.D.N.Y.).(go back)

34Id. at ECF No. 1, ¶¶ 3, 9(a), (f).(go back)

35Id. ¶ 16.(go back)

36A decision is considered “dispositive” if it is a decision that closed the case (i.e., voluntary dismissals are not included), and there are no pending motions for reconsideration or pending appeals. Additionally, decisions on motions to approve settlements are not considered “dispositive” as that term is used herein.(go back)

37The other actions were filed in the E.D.N.Y. (2), the Central District of California (1), and the District of New Jersey (1).(go back)

3820-cv-00577 (S.D.N.Y. Sep. 13, 2022) – ECF No. 61.(go back)

39Id. at p. 1.(go back)

40Id. at pp. 7–8.(go back)

41Id. at p. 23.(go back)

42Id. at pp. 28–29.(go back)

43Id. at p. 24. The court further found that some related statements constituted non-actionable puffery. Id.(go back)

44Id. at p. 48.(go back)

45Id. at p. 46.(go back)

4621-cv-02278 (S.D.N.Y. Sep. 21, 2022) – ECF No. 88.(go back)

47Id. at p. 7.(go back)

48Id. at p. 11.(go back)

49Id. at p. 8.(go back)

5020-cv-11405 (C.D. Cal. Mar. 18, 2022) – ECF No. 73.(go back)

51No. 20-cv-04243 (E.D.N.Y. Apr. 12, 2022) – ECF No. 45.(go back)

52Id. at p. 3.(go back)

53Id. at pp. 3–4.(go back)

54Id. at pp. 10–14.(go back)

5520-cv-08062 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 25, 2022) – ECF No. 40.(go back)

56Id. at p. 13.(go back)

57Although the court found that some statements may have been actionable, namely those concerning loans to purportedly related parties, the court dismissed those claims as being time-barred. Id. at p. 17.(go back)

5821-cv-00317 (E.D.N.Y. Sep. 30, 2022) – ECF No. 63.(go back)

59Id. at pp. 2–3.(go back)

60Id. at p. 4.(go back)

61Id. at p. 8.(go back)

62Id. at p. 11.(go back)

6320-cv-03259 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 14, 2022) – ECF No. 82.(go back)

64Id. at p. 15.(go back)

65Id. at pp. 7–8.(go back)

66Id. at p. 20.(go back)

67Id. at p. 21.(go back)

6821-cv-06013 (S.D.N.Y. July 26, 2022) – ECF No. 70.(go back)

69Id. at p. 2.(go back)

70Id.(go back)

Print

Print