Barnabas Reynolds is head of the global Financial Institutions Advisory & Financial Regulatory Group at Shearman & Sterling LLP. This post is based on a Shearman & Sterling client publication by Mr. Reynolds, Thomas Donegan, and James Webber. Related posts on the legal and financial impact of Brexit include Brexit: Possible Options and Impact, also from Shearman & Sterling; Brexit: Legal Implications, from Sullivan & Cromwell LLP; and The Day After Brexit, from Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft LLP.

[On June 24, 2016], it was announced that the UK public has voted to leave the European Union. There will now be a negotiation of a new relationship between the UK and Europe. The fact of the vote itself has no legal effect on the laws of the UK or EU. The UK will remain a member of the EU until there is either an agreement to exit or expiry of a two-year period after issuance of a formal notice of exit by the UK government. That notice, when served, triggers a negotiation period of up to two years during which time the current EU laws continue to apply in the UK. The UK will lose some of its rights to participate in EU political processes during this period.

This post discusses potential legal models for any post-Brexit negotiated solution in the context of financial business in particular.

Introduction

There are a number of possible models for a new UK deal with the rest of Europe. We discuss these below. It seems unlikely that any of the existing treaty infrastructures underpinning these models will be followed exactly in light of the size and importance of the UK as an economy within Europe and due to some of the policy issues behind the UK’s vote. Instead, a unique new arrangement is likely to be negotiated, perhaps containing some elements of the arrangements that other non-EU countries such as Switzerland or Norway currently have in place (which are outlined below).

One key element of any deal from a financial services perspective will be the status of financial services “passports.” These currently provide financial institutions incorporated within the EU (including the UK) with access to customers and markets across the EU based on a single home country regulatory authorization. Financial institutions can conduct financial business under the passport out of the UK with customers in European countries subject only to UK supervision under broadly EU-based rules, rather than being dually regulated. One possible post-Brexit scenario is for the UK to remain in the European Economic Area (“EEA”), giving it full EU passporting rights. However, this arrangement gives no vote to UK representatives on EU laws and comes with the “free movement of persons.” As immigration from other EU countries has been one of the main issues in the referendum, such an arrangement is probably unacceptable to the UK people. The lack of ability to negotiate would most likely also prove to be a barrier. As a result, some level of tailored access solution is likely to be required even if this starting point were to be adopted. If the UK opts to stay out of any such arrangements with the EU entirely (at least temporarily), in order to get the relationship it wants, it could become what in European parlance is known as a “third country.” There are two passports for third country entities that are being introduced in 2018 under the arrangements known as MiFID II, which give investment firms, and banks in their investment business activities, passports to access for professional and more sophisticated clients. MiFID II may provide the base level framework for a new arrangement for the City with the rest of Europe.

The Different Models

There are several legal models that the UK government could negotiate. These could include:

I. Complete withdrawal from the EU, with new bespoke bilateral agreements that retain freedom of trade and/or establishment, without membership of an existing European bloc.

II. Joining the European Free Trade Association (“EFTA”) and re-joining the EEA (i.e. like Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland).

III. Joining EFTA and relinquishing membership of the EEA whilst gaining access to the European markets through bilateral agreements (i.e. like Switzerland).

IV. Entering into a customs union with the EU (i.e. like Turkey, although the Turkish-EU customs union is limited to trade in goods).

V. Entering into a free trade agreement with the EU within the World Trade Organisation framework (i.e. like Canada).

The map below depicts the countries that are currently in the EEA as well as the candidate EU member states.

Brexit Negotiation Process

The process for exiting the EU is established under the Treaty on European Union. The provisions were inserted into the Treaty after Greenland exited the EU, as there was no mechanism at that time. An exit under the Treaty provisions has therefore not occurred before. The Treaty provides that a member state may withdraw from the EU following the negotiation and conclusion of an agreement with the EU, outlining the exiting member state’s arrangements for withdrawal from the EU and its future relationship with the EU. EU Treaties would cease to apply to the UK upon an agreement taking effect or the expiry of two years from the date of the UK’s notification to exit from the EU. The UK could apply to the European Council for an extension of the two-year period. Approval of any such extension requires unanimous consent of the other EU heads of state. Agreement to leave only needs a qualified majority vote at Council and majority ratification by Parliament, not unanimity.

In principle, the exit process could be triggered by the UK once a new arrangement has been negotiated; or it could be triggered before negotiations have been finalised. After notice is given, the UK would no longer have a presence in European Parliament and the exit negotiations would be led within the EU by representatives of the remaining EU member states in the relevant institutions. If no agreement is settled within the prescribed two-year period, and no extension of time is granted, the UK will be deemed to have effectively exited the EU and all associated constitutional, trade and other arrangements would largely cease to apply, unless other steps are taken.

Transitional arrangements necessary for the two-year period to be observed will add a layer of complexity concerning: (i) the validity of existing EU legislation; (ii) the nature of the legislation, in particular, whether it is directly effective or not; and (iii) the terms of the exit.

UK Legal Framework for EU Membership: Background

The UK legal framework for its EU membership and the manner in which it fulfils its current EU obligations is found in the European Communities Act 1972 (“ECA”). The ECA provides for all pre-existing EU texts to apply as UK law, although the method of transposition varies depending on the nature of the EU legislative instrument. All “directly effective” EU legislation (i.e. EU regulations and certain articles of the EU treaties) is automatically incorporated into national law without the need for further enactment through an Act of Parliament. In practice, some UK legislative changes are often needed to eliminate any inconsistencies with a particular EU regulation. In contrast, EU directives are binding on EU member states but require national implementation measures, often done in the UK by statutory instrument under authority of the ECA. In addition, in sectors which are subject to regulation, such as financial services, rules and guidance are often issued by the regulators to implement or further detail the requirements. It is unclear what will replace the ECA on a Brexit or whether existing EU legislation would be grandfathered.

EU law includes the principle of direct effect. EU law may be of vertical direct effect, which means that individuals can invoke an EU provision in relation to a country, or of horizontal direct effect which means that an individual can invoke an EU provision in relation to another individual. The EU treaties are of direct effect, both vertically and horizontally, provided that the obligations are precise, clear, unconditional, do not require additional measures at either national or European level and do not give member states any discretion. EU regulations are always of direct effect, both horizontally and vertically. EU directives are of vertical direct effect when the provisions are unconditional, clear, precise and have not been transposed by the relevant member state by the required deadline.

Another key EU principle is the precedence principle, which provides that European law is superior to the national laws of member states and that member states may not apply a national law that is contrary to European law. If a member state law is contradictory to EU law, then the member state law is invalid. The precedence principle applies to all EU laws of binding force—the treaties, regulations, directives, decisions and international agreements. The Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) is responsible for ensuring compliance with both the precedence principle and the principle of direct effect.

These EU laws will remain in effect during the period after the termination notice has been served. After a post-Brexit agreement has been reached or the two-year notice period has expired, UK law would prevail in its entirety (as a matter of EU law) and EU courts would cease to have competence over UK issues. The ECA would have to be amended through a new Act of Parliament in the UK. Also, any EU measures which the UK wishes to retain will have to be enacted to form part of UK law, either specifically or through national grandfathering legislation. Interpretations could also change somewhat, since the CJEU will no longer be the ultimate arbiter of the meaning of previously EU provisions.

Complete Exit from EU

The most extreme option is complete withdrawal from the EU without a meaningful new relationship post-Brexit. All EU legislation, including treaties, would cease to form part of UK law.

Effect of Brexit on Existing EU Regulatory Framework

Legal Implications

On any Brexit situation, the ECA will need to be repealed or substantially amended. This will require an Act of Parliament. Interestingly, this will be against a backdrop where probably no more than a third of MPs have openly supported Brexit. Any amendment to, or removal of, the legislative framework for implemented EU law will have several constitutional, administrative and practical implications relevant to a broad field of laws implemented under the ECA. In addition, EU regulations will cease to apply in the UK. This means that a grandfathering system would need to be implemented or a large legislative drafting exercise undertaken or a combination of both followed by a review to assess which laws the UK wants to keep, remove or tailor. This will be particularly important in areas where EU legislation on a particular issue has been implemented by both regulation and directive. For example, the EU legislative framework on capital standards for banks is contained in the Capital Requirements Regulation (“CRR”) (of direct effect in the UK) and the Capital Requirements Directive (“CRD IV”) (which has been implemented through UK legislation). Without a grandfathering system or new laws being drafted expeditiously to replace the EU legislation, the UK legislation implementing CRD would not, without the CRR sitting alongside it, have practical application. This situation would lead to legal uncertainty.

In theory, UK and EU businesses currently operating on a cross-border basis may find that they have to comply with different (unharmonised) laws in both the UK and a post-Brexit EU, although it seems likely that arrangements would be put in place to prevent that. All references to EU bodies such as the European Securities and Markets Authority (“ESMA”) and the European Commission in UK legislation will need to be removed.

Financial Services Sector

Loss of Influence over EU Legislation but ability to Develop more Free-Market UK Legislation

By revoking its membership of the European Union, the UK will lose its ability to influence directly in the framing of any EU legislation. This is mostly viewed as a negative aspect of leaving the EU. However, the corresponding increase in national sovereignty would also present an opportunity to remove or modify those aspects of EU legislation that the UK has opposed in the past, for example, the bonus cap for bankers and the framework for marketing and managing funds under the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (“AIFMD”). Many more examples abound. The UK will now need to negotiate its access to the EU markets through bilateral agreements. If one looks at the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (“CETA”), the EU appears to be more willing than in the past to create favourable terms for the financial services sector. For individual pieces of legislation where equivalence determinations are required, the UK could likewise request some kind of access on the basis that, while its laws do not exactly mirror those of the EU, they achieve similar outcomes and there is no threat to the financial stability of the EU.

Whether and how UK businesses would have access to the EU after membership is revoked will depend on what substitute arrangements are negotiated between the UK and EU. Some financial businesses have announced that they would move some staff and operations to continental Europe, presumably if “passporting” was not replicated in a post-leave settlement. It is difficult to predict what would happen in any Brexit situation.

However, it does seem inconceivable that the UK government would seek to manage Brexit in such a way as to damage the City and broader national economy.

The converse situation of EU firms’ access to the UK post-Brexit would contrast starkly, at least under current laws. Pursuant to the UK’s “overseas persons exclusion,” all EU and non-EU firms have access to wholesale UK markets. This exclusion allows a non-UK firm to enter into certain regulated activities (such as dealing in derivatives as principal or agent) with UK client or counterparties from outside the UK, without needing to be authorised, provided that the firm enters into transactions with or through a locally regulated entity or if marketing laws are complied with. Despite the UK voting to leave the EU, the overseas persons exclusion will continue to apply to EU firms for the time being. As regards branches of EU firms, many of these are likely to have to subsidiarise, with consequent capital consequences, since the UK takes the view that any significant or systemically risky business should be conducted through subsidiaries. This situation is a considerable negotiating chip for the UK since EU firms will require access to the UK’s markets in order to conduct many forms of business.

Cross-Border Passporting Regimes

Full exit from the EU will result in loss of access to the EEA single financial market and the corresponding rights to freedom of trade and establishment. Various laws allow EEA banks, brokers, exchanges, fund managers, clearing houses, funds and payment service providers the right to “passport” into other EEA member states without the need for further regulatory approval. Passport rights can be exercised by either establishing a branch or providing services cross-border in the other member state. The basis of the EEA “passporting system” is founded in the Treaty on European Union and the EEA Agreement, in particular the freedoms of establishment and provision of services, but has been built upon in legislation by sector. Some freedoms of access have not been implemented or replicated in domestic UK legislation and are instead directly effective in the UK by virtue of the UK’s accession to the EU or because they are in EU regulations.

Reduced Access to EU Financial Markets?

The EU has set up a framework through which financial institutions, insurers and reinsurers, funds and market infrastructure (trading venues, central counterparties, trade repositories, benchmark administrators and central securities depositories) established outside of the EU (third countries) can access European investors and markets. For these financial sector participants to access the EU markets, in addition to being properly authorized and supervised in their own countries, there are various requirements relating to the legal and regulatory regime of those countries that need to be fulfilled. The requirements vary by sector but typically revolve around the “equivalence” of the third country regime to the EU regime, co-operation arrangements between the third country and EU countries or ESMA and the anti-money laundering and tax arrangements in the third country.

Access to the EU markets for these UK-established financial sector participants will therefore depend on how closely aligned the UK’s legal and regulatory regime is to the EU regime. It is likely that initially the UK’s regime would be deemed automatically equivalent to the EU regime for those areas where the UK has already adopted EU laws (for example, under the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (“EMIR”)) but this depends on how the UK approaches grandfathering. For those areas where EU legislation is due to be introduced or which have not been fully implemented in the UK, equivalence determinations would need to be made and a negotiation would be required. Equivalence determinations can take time if there are material differences to be considered. The UK would need to ensure that its financial regulatory regime achieved similar outcomes to that of the EU regime if it wanted any immediate access.

The Impact of MiFID II

For the passporting of investment businesses, the position could be largely unaffected at least in the medium to short term, assuming MiFID II comes into effect on schedule. The current date for implementation of MiFID II has recently been moved from 3 January 2017 to 3 January 2018. MiFID II will therefore come into force during the 2-year exit period.

MiFID II allows non-EU firms to provide wholesale services on a cross-border basis across the EU upon registration with ESMA, subject to those services only being provided to wholesale clients and the authorisation of the firm in its own country covering the same services. Registration with ESMA requires, amongst other things, an equivalence determination that the conduct and prudential rules of the relevant third country are equivalent to those in the EU. Non-EU firms that want to provide wholesale services across Europe may alternatively do so through a retail branch which is authorised in a relevant member state, again subject to certain conditions most notably including equivalence.

The timing of the UK’s exit from the EU and the effective date for MiFID II is key for the passporting of investment business and how these businesses structure themselves to gain access to the EU markets and investors.

The above considerations will apply equally if the UK entered into a Customs Union with the EU or if it adopted the Swiss or the Canadian models. Each of these options is discussed below.

Joining EFTA and Re-joining the EEA

The Transition

EFTA was created in 1960 as a separate organization from the European Economic Community (which is the precursor to the EU). Like the EU, EFTA’s goal is to establish free trade, but it does not adopt uniform external tariffs and does not include the establishment of supranational institutions such as the European Commission, Council of the European Union or the CJEU. There are currently four countries in EFTA—Iceland, Norway, Liechtenstein and Switzerland (the “EFTA States”). Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein are also members of the EEA (the “EEA EFTA States”). The EEA is made up of the EU member states and the three EEA EFTA States.

The UK is currently a member of the EEA as a result of its EU membership. Upon exiting the EU, it could re-join the EEA by joining EFTA as an EEA EFTA State.

There are various challenges, both legal and political, involved in joining EFTA. The existing EFTA States would have to agree to the UK’s accession to the EFTA Convention and the terms and conditions for doing so would need to be negotiated. The current EFTA States are fairly homogenous in terms of their size, economic development and trade preferences. They may have concerns regarding the UK’s suitability and other changes which could be perceived as being to their disadvantage.

From a legal perspective, the route to leaving the EU and becoming an EEA EFTA State will likely require three new treaties. It will involve negotiations with all of the EU member states and the EFTA States. The agreements that will need to be entered into are between:

- all current EU member states on the UK’s withdrawal from the EU (or two years’ expiry post exit notice, as above);

- the EFTA States and the UK agreeing to the terms of the UK’s EFTA accession; and

- remaining EU member states, the EEA EFTA States and the UK, formalizing the UK’s EEA membership based on it becoming a member of EFTA.

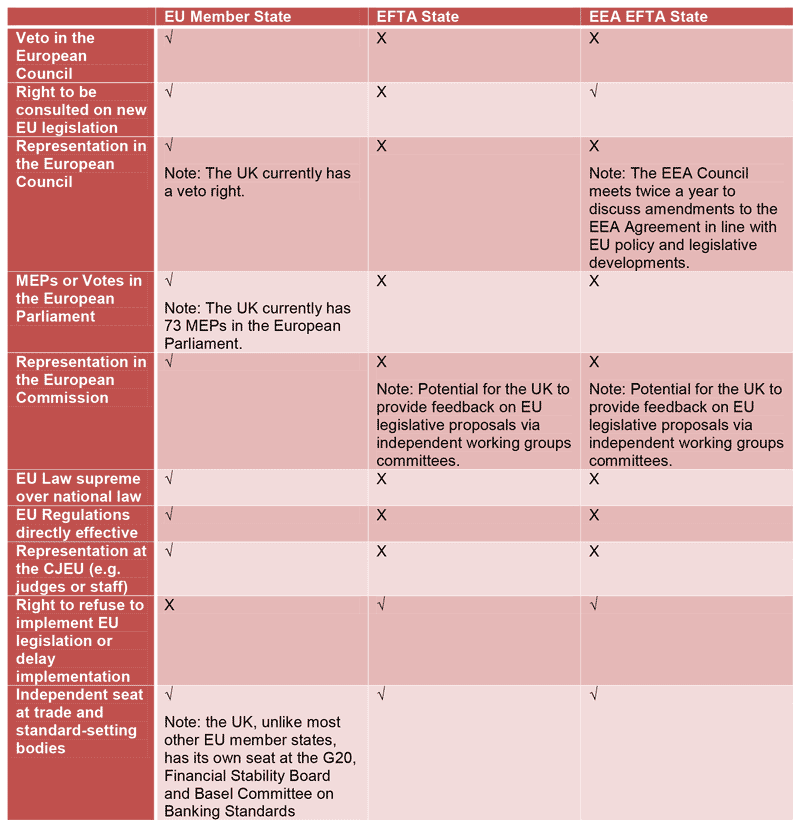

The main differences between being an EU member state, an EFTA State and an EEA EFTA State are set out in Table A below.

Legal Differences

In terms of substance, EU law will likely continue to apply in a similar manner should the UK become an EEA EFTA State. The EEA EFTA legislative process primarily consists of making “appropriate amendments” to the EEA Agreement to ensure that it reflects the body of EU legislation that is EEA-relevant. Once an EEA-relevant piece of legislation has been formally adopted by the EU, the Joint Committee of the EEA then decides whether to amend the EEA Agreement “with a view to permitting a simultaneous application” of legislation in the EU and the EEA EFTA States. All of the EEA EFTA States must agree to the adoption of the legislation. To date, the majority of EU legislation with EEA relevance is adopted by the EEA joint Committee into the EEA Agreement.

The EEA institutional structure also has supervisory mechanisms to ensure that implementation of EU legislation “with EEA relevance” is appropriately monitored. This structure mirrors the supervision of compliance by member states within the EU. Once implemented, EU legislation “with EEA relevance” is therefore enforced through the EFTA Surveillance Authority (which mimics the European Commission) and the EFTA Court (which mimics the CJEU).

Impact

EEA EFTA States do not have a right to negotiate or seek to influence EU law or policy as an EU member state. The EEA EFTA States have the opportunity to contribute to the work that the European Commission does before proposing new EU legislation. However, they have little or no formal opportunity to influence the Council of the European Union or the European Parliament who take the final decisions on all EU legislation.

As an EEA EFTA State, the UK would have certain access to European markets. As a counterpoint to this, the UK should be able to increase control of access to its territorial waters for activities such as fishing. The UK would also no longer need to contribute to the “common agricultural policy” (a subsidy scheme for European (including, currently, UK) farming). However, access to EU markets for these activities and their products might become subject to tariffs. The UK would not be a part of the EU customs union, which means that any trade in goods between the UK and the EU would be subject to customs procedures and any beneficial rates could only be obtained if additional criteria were found to be met.

The UK would need to negotiate its own trade and investment deals with countries outside of the EU. It could do this on its own or through EFTA.

There would be no automatic right to participate in the EU cooperation on police and criminal justice. The UK would need to negotiate a bilateral agreement with the EU to establish such arrangements.

Becoming an EEA EFTA State would, notably, include signing up to the “free movement of people” from both EU and EEA countries. EU immigration has been widely cited in public discourse as a key consideration by politicians that championed Brexit, so becoming an EEA EFTA State under the current framework may be unattractive to politicians and the UK public.

Financial Services Sector

Retention of Cross-Border Passporting Rights

Joining EFTA and becoming an EEA EFTA State would mean that UK entities would retain their cross-border passporting rights. The passport rights would be based on the EEA Agreement instead of the Treaty on European Union.

Loss of Access to EU Financial Markets

To the extent that any EU legislation has not been incorporated into the EEA Agreement, the EU framework for entities established outside of the EU to access European investors and markets would apply to the relevant UK entities (see above discussion under “Complete Exit from the EU”). To date, there are several significant pieces of EU legislation which have not been incorporated into the EEA in the area of financial services, for example, EMIR. If EMIR is incorporated, then presumably a UK clearing house or central counterparty (“CCP”) would remain entitled to provide services in the EU and would not be considered a CCP that should be subject to the third country regime. The position is less clear for a UK trade repository. Unlike CCPs, which are authorised and supervised by regulators in their country of establishment, an EEA trade repository would be recognised and supervised centrally by ESMA. Some form of cooperation arrangement would need to be found.

Joining EFTA but Exiting the EEA: the Swiss Model

This would entail becoming an EFTA State (see discussion above) and leaving the EEA. The same position would apply for the situation where the UK opted to become an EEA EFTA State with regard to trade and investment deals with countries outside of the EU and cooperation on police and criminal justice. For access to the EU internal market the UK would need to negotiate bilateral agreements. Switzerland has only partial access to the internal market. Some products, such as agriculture, remain subject to tariffs. As a non-EU member state, some trade deals between the UK and the EU would be subject to the common external tariff.

The EU imposes a common external tariff on exports from countries outside the EU, except those countries that have negotiated preferential trade agreements with it. The increased costs associated with any such tariffs would be compounded by additional administrative burdens, such as customs.

For the financial services sector, if not included in any of the bilateral trade agreements, the position would be the same as that discussed above under “Complete Exit from the EU.”

Customs Union: the Turkish Model

The UK could seek to participate in a Customs Union with the EU, similar to that which Turkey has negotiated. This would mean that the UK would have partial access to the EU markets. Customs checks would not be required for goods falling within the UK-EU Customs Union (which would depend on the outcome of negotiations). As part of a Customs Union, the UK would need to implement rules equivalent to the EU rules for the relevant areas, such as competition, environmental rules and state aid. The UK would also need to negotiate trade agreements with any non-EU countries. However, tariffs under those agreements would need to match the EU tariffs.

The same implications for the financial services sector that apply to the Swiss model would apply under this model. Note that on any model where the UK does not take the benefit of European to third country trade arrangements, new treaties with other (non-EU) countries will also be needed.

Free Trade Agreements: the Canadian Model

Under this model, there would be more limited access to the EU markets but also fewer obligations on the UK. The UK would negotiate the market access arrangements and tariff levels with the EU and set quotas for trade between the EU and the UK. Currently, final approvals are pending before CETA can be implemented. The agreements are negotiated by the European Commission but must be approved by member states and the European Parliament.

While the EU acknowledges that CETA goes further than any other trade agreement, it does not grant Canada full access to the EU markets. If the provision of financial services was not included in any such trade agreement, the same issues that would arise upon a full exit from the EU would apply in this scenario (see discussion above).

Other Issues

Human Rights

The European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (known as the “European Convention on Human Rights” or “ECHR”), along with immigration laws, is among the pieces of legislation that were highlighted in public discourse on Brexit as being objectionable. For example, the UK has been under continuing pressure to change its law with regard to voting rights for prisoners as a result of various decisions by the European Court of Human Rights. However, this is not an EU body.

The UK has ratified the ECHR. It has also implemented the ECHR into its national law through the Human Rights Act 1998 (“HR Act”). The principal purpose of the HR Act is to give power to the UK courts to decide issues that fall under the ECHR, albeit that the courts must still follow the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights. Any judgment of the European Court of Human Rights under the ECHR is binding on the country to which the decision applies.

The HR Act provides that UK legislation must be given effect to the extent possible in a way which is compatible with the rights set out in the ECHR. If a UK court is satisfied that a provision of UK legislation is incompatible with one of those rights, it may make a declaration of incompatibility. Such a declaration does not affect the validity, continuing operation or enforcement of the provision and is not binding on the parties to the proceedings in which it is made. However, upon a declaration of incompatibility being made, the UK Parliament has powers to revoke or amend the relevant UK legislation.

Revocation of EU membership will not terminate membership of the Council of Europe and the UK will continue to remain in the ECHR. Both the ECHR and the HR Act would remain law. Therefore, any rights protected under the ECHR and HR Act would remain in place even if the UK votes to leave the EU. If the UK seeks to withdraw from the ECHR, it will need to cease membership of the Council of Europe, which is a separate matter.

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print