Filippo Lancieri is a Postdoctoral Researcher at ETH Zurich and a Research Fellow at the Stigler Center at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, and Luigi Zingales is the Robert C. McCormack Distinguished Service Professor of Entrepreneurship and Finance at University of Chicago Booth School of Business. This post is based on their recent paper.

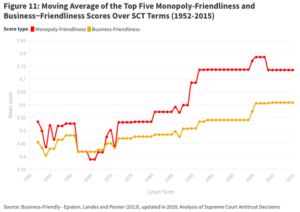

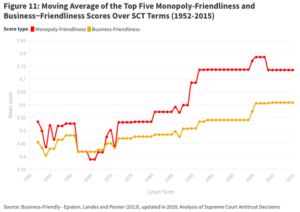

According to a familiar narrative, the demise of antitrust enforcement in the United States was caused by the spreading of the Chicago School approach to antitrust. In the late 1960s and 1970s, scholars affiliated with or trained at the University of Chicago challenged U.S. antitrust law by arguing that antitrust enforcement was incoherent and harmful to competitive markets. They argued that antitrust should be based on economic principles of price theory and industrial organization, with emphasis on maximizing consumer welfare, and argued that antitrust law and enforcement should be narrowed. These ideas found receptive ears in different administrations and in the U.S. judiciary, which significantly reduced civil antitrust enforcement.

This is a positive story of “enlightened technocrats” reflecting the best ideas in academia in their design of law and public policy. The major evidence for this theory is that Chicago-School ideas (and accompanying citations) made their way into supreme court opinions, lower court opinions, and various guidance documents issued by regulators, and that indeed the law and enforcement priorities moved radically in the direction of Chicago views in the decades following their publication.

However, this narrative raises several questions. First, the stated objective of the Chicago School approach was to improve antitrust enforcement and increase market competition by focusing antitrust policy on the most serious violations (for example, price-fixing), while limiting its impact on other types of commercial behavior that could be understood as pro-competitive (for example, vertical restraints). Yet the evidence indicates that market competition declined and markups increased during the era of Chicago-School ascendency. Second, the Chicago School approach was almost immediately challenged by economists who rejected its simple price-theoretical approach—many drawing on the burgeoning fields of game theory and information economics. By the 1980s and 1990s, the “post-Chicago” approach had largely overtaken the earlier Chicago view in economics departments and law schools. If the enlightened technocratic story were to be believed, the post-Chicago view would have displaced the Chicago view in law and policy, but it has not, except on the margins. Third, the enlightened technocrat narrative does not explain (or demonstrate) causation between the emergence of the ideas and the implementation of policy. Indeed, it flies in the face of another contribution of the University of Chicago: public choice theory. George Stigler, an exponent of the Chicago School, famously affirmed that “as a rule, regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefit”. Yet the technocratic narrative assumes exactly the opposite—that an antitrust law that benefited inefficient producers was replaced by an antitrust law that advanced the public interest.

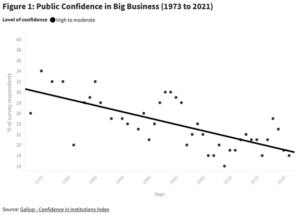

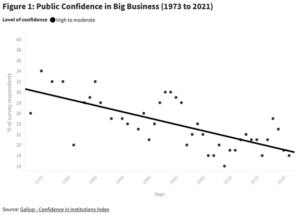

In a new working paper (from where we base this contribution) we focus on the political economy of the decline of antitrust enforcement between the 1950s and today. We start by documenting the decline in US civil antitrust enforcement since the mid-1970’s. We then move to establish that this decline was not driven by voters’ preferences. Our conclusion is based on an examination of polling data, presidential speeches, and related sources.

In American democracy, elected officials are not required to follow the polls; they may use their discretion in determining policy and then take their chances during elections. The president also appoints powerful regulators with the consent of the senate, and those regulators too enjoy significant policy discretion. Our analysis then considers these more complex forms of public accountability. We start by looking at instruments employed by elected officials—the passage of new laws and the enactment of Presidential Executive Orders—and then look at regulations, nomination hearings, enforcement decisions, and judicial decisions. We find that elected officials have almost never used their powers in an overt way to restrict antitrust law—either directly (by passing laws or issuing executive orders) or indirectly (by nominating or voting to confirm judges and regulators who during confirmation hearings publicly advocated restriction of antitrust enforcement). For example, antitrust was not a salient topic during the nomination hearings of Supreme Court nominees until the rejection of Robert Bork in 1987—when Bork received significant pushback for his antitrust views. From then on, most justices gave assurances that they would promote strong enforcement. However, they did otherwise once they reached the Court, and in a manner that was significantly more salient than their pro-business votes.

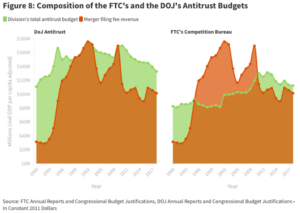

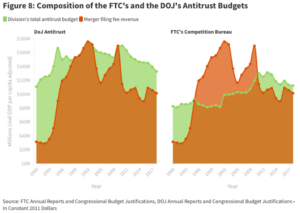

Indeed, nearly all key decisions that reshaped antitrust policy were made by regulators and judges with relatively little democratic accountability. These range from internal FTC and DOJ prioritization to hidden budget cuts sponsored by Congress.

These data, however, are not enough to separate the enlightened technocrat story from a potential capture of public policy. To disentangle both explanations, we focus on overall economic outcomes, opportunities and mechanisms.

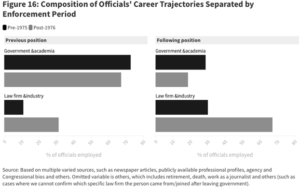

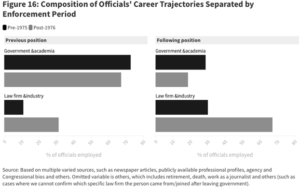

There is more and more evidence that the weakening of antitrust enforcement that has continued in an almost steady manner since the mid 1970’s did not increase overall economic efficiency—rather, it benefited big businesses. We bolster this hypothesis by examining a range of historical factors starting in the 1970s that explain why big business would turn its attention to antitrust enforcement and how business obtained advantages in the public arena, allowing it to push forward an anti-antitrust agenda. These range from increases of international imports to an explosion in the revolving doors targeting FTC and DOJ officials.

We have no smoking gun—special interests do not openly promote their attempts to influence policy to their benefit. Nonetheless, the evidence points in a single direction: big businesses greatly promoted the Chicago School as a driver of antitrust enforcement because it benefitted from its lax views, and this behind the doors influence was the major reason why it has dominated US antitrust policy since then.

The complete paper is available for download here.